Download Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psaudio Copper

Issue 77 JANUARY 28TH, 2019 Welcome to Copper #77! I hope you had a better view of the much-hyped lunar-eclipse than I did---the combination of clouds and sleep made it a non-event for me. Full moon or no, we're all Bozos on this bus---in the front seat is Larry Schenbeck, who brings us music to counterbalance the blah weather; Dan Schwartz brings us Burritos for lunch; Richard Murison brings us a non-Python Life of Brian; Jay Jay French chats with Giles Martin about the remastered White Album; Roy Hall tells us about an interesting day; Anne E. Johnson looks at lesser-known cuts from Steely Dan's long career; Christian James Hand deconstructs the timeless "Piano Man"; Woody Woodward is back with a piece on seminal blues guitarist Blind Blake; and I consider comfort music, and continue with a Vintage Whine look at Fairchild. Our reviewer friend Vade Forrester brings us his list of guidelines for reviewers. Industry News will return when there's something to write about other than Sears. Copper#77 wraps up with a look at the unthinkable from Charles Rodrigues, and an extraordinary Parting Shot taken in London by new contributor Rich Isaacs. Enjoy, and we’ll see you soon! Cheers, Leebs. Stay Warm TOO MUCH TCHAIKOVSKY Written by Lawrence Schenbeck It’s cold, it’s gray, it’s wet. Time for comfort food: Dvořák and German lieder and tuneful chamber music. No atonal scratching and heaving for a while! No earnest searches after our deepest, darkest emotions. What we need—musically, mind you—is something akin to a Canadian sitcom. -

MS Mus. 1738. Music Manuscripts of the Composer Robert Simpson (B.1921; D.1997); 1942-1997, N.D. Manuscripts Are Autograph Except Where Specified Otherwise

THE ROBERT SIMPSON COLLECTION AT THE BRITISH LIBRARY MS Mus. 1738. Music manuscripts of the composer Robert Simpson (b.1921; d.1997); 1942-1997, n.d. Manuscripts are autograph except where specified otherwise. Presented by Angela Simpson on 9 June 2000, with additional material subsequently received from the archives of the Robert Simpson Society (formerly housed at Royal Holloway, University of London), and from individual donors. See also MS Mus. 94, the autograph manuscript of Simpson’s String Quartet no. 7. The collection is arranged as follows: MS Mus. 1738/1 Symphonies MS Mus. 1738/2 Concertos MS Mus. 1738/3 Other orchestral music MS Mus. 1738/4 Incidental music MS Mus. 1738/5 Music for brass band MS Mus. 1738/6 Vocal music MS Mus. 1738/7 String quartets MS Mus. 1738/8 Other chamber music MS Mus. 1738/9 Keyboard music MS Mus. 1738/10 Arrangement MS Mus. 1738/11 Miscellaneous sketches MS Mus. 1738/1. SYMPHONIES MS Mus. 1738/1/1. Robert Simpson: Symphony no. 1; 1951. Score, in green ink, with various ink and pencil annotations. Dated at the end ‘21. vii. 1951 at Muswell Hill’. Submitted by the composer for his doctorate at the University of Durham in 1951. First performed in Copenhagen on 11 June 1953. Published by Alfred Lengnick & Co, 1956. Presented by the Robert Simpson Society in 2006. ff. i + 73. Green buckram binding. MS Mus. 1738/1/2. Robert Simpson: Symphony no. 2; 1955-1956. Score, in ink, with numerous ink and pencil annotations. Dedicated to Anthony and Mary Bernard. Published by Alfred Lengnick & Co., 1976. -

TEM Issue 153 Cover and Front Matter

Tempo PETER MAXWELL DA VIES Stephen Pruslin considers the symphonies ... so far NED ROREM Bret Johnson on the major works of the past 15 years 'DIE LIEBE DER DANAE' Kenneth Birkin on Richard Strauss's least-known opera ROBERT SIMPSON'S 'NEW WAY' Lionel Pike analyses the Eighth String Quartet BERIO ENGLISH MUSIC SCOTS FOLKSONG TRUSCOTT No. 153 £1.00 REVIEWS NEWS SECTION Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 27 Sep 2021 at 03:21:27, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298200059350 CONTRIBUTORS STEPHEN PRUSLIN has just been devising and recording the musical vignettes for the Radio 3 series New Premises. His recording of Maxwell Davies's Piano Sonata on Auracle AUC 1005 was chosen by Edward Greenfield as the outstanding contemporary disc of 1984. In June, Pruslin was on the jury of the 1985 Carnegie Hall International Piano competition and in July will be harpsichord soloist in the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto at The Berliner Bach- Tagen. BRET JOHNSON'S principal music activities are with the Mary Magdalen Music Society, Paddington: last year he devised, performed and conducted a programme of American music including several UK premieres there. KENNETH BIRKIN is researching into Strauss's late operatic collaborations with Stefan Zweig and Josef Gregor, on which he has published articles in the Richard-Strauss Blatter. LIONEL PIKE teaches at the Department of Music, Royal Holloway College (University of London), where he is also Director and organist of the Chapel Choir. -

Oskar Łapeta Phonographic Realisations of the Gothic Symphony by Havergal Brian

Oskar Łapeta Phonographic Realisations of the Gothic Symphony by Havergal Brian Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ nr No. 37 (2), 161-176 2018 Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ No. 37 (2/2018), pp. 161–176 DOI 10.4467/23537094KMMUJ.18.025.9169 www.ejournals.eu/kmmuj Oskar Łapeta University of Warsaw Phonographic Realisations of the Gothic Symphony by Havergal Brian Abstract Havergal Brian’s Symphony No. 1 in D minor (1919–1927), known as Gothic Symphony, is possibly one of the most demanding and difficult pieces in symphonic repertoire, the largest-scale symphony ever written, outdoing the most extreme demands of Mahler, Strauss and Schönberg. After the purely instrumental part 1, part 2 is a gigantic setting of Te Deum, inspired by the mighty Gothic cathedrals. This outstanding work has been per- formed only six times since its premiere in 1961, and has been recorded in studio only once. There are three existing phonographic realisations of this work. Two of them are live recordings made in England. The first of them comes from 1966, when the Symphony was recorded under the direction of Adrian Boult (it was released by the Testament label under catalogue num- ber SBT2 1454) and the second one was made in 2011 under the baton of Martyn Brabbins (it was released in the same year under catalogue number CDA67971/2). The third recording, but the first one that has been available internationally, was made in Bratislava in 1989 under Ondrej Lenárd (it was first released by Marco Polo label in 1990, and later published by Naxos in 161 Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ, No. -

Download Booklet

572014 bk Brian 29/4/10 12:04 Page 12 Also available Havergal BRIAN Symphonies Nos. 11 and 15 RTE´ National Symphony Orchestra Tony Rowe • Adrian Leaper 8.570308 8.572014 12 572014 bk Brian 29/4/10 12:04 Page 2 Havergal Brian (1876-1972) Also available For Valour • Doctor Merryheart • Symphonies Nos. 11 and 15 Havergal Brian was never a conventional composer, but of that year’s Promenade season. The work was next the three later works on this disc, very different from played in 1911, at Crystal Palace, under Samuel one another, rank among his most unconventional Coleridge-Taylor, and Thomas Beecham conducted it in approaches to symphonic form. Their common feature, Birmingham in 1912. The score was printed by however, is the way they concentrate on developing Breitkopf & Härtel in 1914, and was actually on the short motivic cells to create a large-scale form even presses at the outbreak of World War I (perhaps when the music appears to be shaped by other dictates, unsurprisingly, copies are scarce). As published, For such as an extra-musical programme (as in Doctor Valour is dedicated to Brian’s friend Dr Graham Little – Merryheart), or free-flowing associations of mood the extant manuscript bears no dedication, yet according (Symphony No. 11). to The Staffordshire Sentinel’s 1905 report, the original The overture For Valour, by contrast, is more dedicatee was A.F. Coghill (a clergyman and benefactor obviously patterned after an orthodox idea of musical of the North Staffordshire Triennial Festival, who later form, albeit one that he treats in his own individual way. -

Comments for Cds on Klassic Haus Website - January Releases Series 2013

Comments for CDs on Klassic Haus website - January Releases Series 2013 KHCD-2013-001 (STEREO) - Havergal Brian: Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1930-31) - BBC Symphony Orchestra/Sir Charles Mackerras - It is by now almost common knowledge among the cognoscenti of classical music that Havergal Brian (1876-1972) wrote 32 symphonies, starting with the enormous and still-controversial Gothic, and suffered decades of neglect. He was born in the same decade as composers like Ravel, Scriabin and Ralph Vaughan Williams, but his style belongs to no discernable school. Of course, he had his influences (Berlioz, Wagner, Elgar and Strauss spring to mind), but he digested them thoroughly and never really sounds like anyone else. Between 1900 and 1914, Brian briefly came to notice with a series of choral works and colourful symphonic poems. Then World War I broke out, and everything changed, not least his luck as a composer. But, although many decades of neglect lay in store for him, Brian found himself, too. By the end of World War II, therefore, he had written five symphonies, a Violin Concerto, an opera, The Tigers, and a big oratorio, Prometheus Unbound (the full score of which is still lost), all of them works of power and originality, and all of them unplayed for many years to come. Havergal Brian was already in his seventies. His life’s work was done, so it seemed. The opposite was the case. Symphony No. 2 in E minor was written in 1930-31. In it Brian tackles the purely instrumental symphony for the first time, after the choral colossus which is the Gothic. -

Oboe in Oxford Music Online

14.3.2011 OboeinOxfordMusicOnline Oxford Music Online Grove Music Online Oboe article url: http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com:80/subscriber/article/grove/music/40450 Oboe (Fr. hautbois ; Ger. Oboe ; It. oboe ). Generic term in the system of Hornbostel and Sachs for an aerophone with a double (concussion) reed (for detailed classification see AEROPHONE ). The name is taken from that of the principal treble double-reed instrument of Western art music (see §II below). I. General 1. Oboes. The AULOS of ancient Greece may sometimes have had a double reed, and some kind of reed aerophone was known in North Africa in pre-Islamic times. Instruments of the SURNĀY type became established with the spread of the Arab empire around the end of the first millennium CE; they were possibly a synthesis of types from Iran, Mesopotamia, Syria and Asia Minor. From there the instrument, then used in a military role, spread into conquered areas and areas of influence: to India, and later, under the Ottoman empire, to Europe (around the time of the fifth crusade, 1217–21; there may already have been bagpipes with double reeds there) and further into Asia (to China in the 14th century). As the instrument spread, it came to be made of local materials and fashioned according to local preferences in usage, shape and decoration: the ŚAHNĀĪ of north India has a flared brass bell; the SARUNAI of Sumatra has a palm leaf reed and a bell of wood or buffalo horn; the ALGAITA of West Africa is covered with leather and has four or five finger-holes. -

June 2018 List

June 2018 Catalogue Issue 26 Prices valid until Friday 27 July 2018 unless stated otherwise 0115 982 7500 The Temptation of St Anthony (detail from right hand panel) by Hieronymus Bosch (used as the cover for Stephen Hough’s Dream Album (Hyperion CDA68176). [email protected] Your Account Number: {MM:Account Number} {MM:Postcode} {MM:Address5} {MM:Address4} {MM:Address3} {MM:Address2} {MM:Address1} {MM:Name} 1 Welcome! Dear Customer, Welcome to another bumper catalogue! It never ceases to amaze us how quickly our monthly publications get filled, especially when classical music was supposed to be ‘dead’ many years ago. New releases continue to number in their hundreds every month, and it is certainly not difficult to find superb back-catalogues to promote and explore. Our ‘Disc of the Month’ is as good a place as any to start for our new release highlights: Stephen Hough’s recitals for Hyperion never fail to ignite a spark of interest, and his latest compendium features a delightful selection of both romantic and light piano repertoire, many arranged by Hough himself. We have been thoroughly enjoying it in recent days, making it a clear choice for our pick in June - please find more information below. Another pianist we think deserves some attention this month is Kevin Kenner, who has recorded a brand new album of Chopin’s late works for Warner Classics. Kenner has long been associated with Chopin and his interpretations have been compared in the past to the likes of Rubinstein, Michelangeli and Lipatti, so it is pleasing to see him now receiving some long-overdue exposure on a major label in the UK. -

Requiem for Baritone, Chorus and Orchestra (Lost) C. 19

HAVERGAL BRIAN: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL AND CHORAL MUSIC c.1899: Requiem for baritone, chorus and orchestra (lost) c. 1900-02: Tragic Prelude for orchestra (lost) 1902/06: Overture “For Valour”, op.7: 15 minutes + (Cameo Classics and Naxos cds) c.1902-04: English Suite No.1, op.12: 26 minutes + (Cameo Classics cd) 1903: Burlesque Variations on an Original Theme for orchestra, op.3: 27 minutes + (Cameo Classics and Toccata cds) c.1903-04: Legende for orchestra, op.4 (lost) c.1904-06: Symphonic Poem “Hero and Leander”, op.8 (lost) c.1904/ 1944-46: Psalm 23 for tenor, chorus and orchestra: 16 minutes * + (Classico cd) 1905/09: “By the Waters of Babylon” for baritone, chorus and orchestra, op. 11 (lost) 1906: “Carmilhan” for soloists, chorus and orchestra (lost) c.1906-07: “Let God Arise” for soloists, chorus and orchestra (lost) 1907-08: A Fantastic Symphony: two movements lost, other two reused as- 1907: Fantastic Variations on an Old Rhyme for orchestra: 11 minutes + (Cameo Classics and Naxos cds) 1908: Festal Dance for orchestra: 8 minutes + (Naxos cd) Cantata/ Tragic Poem “The Vision of Cleopatra” for soprano, mezzo-soprano, contralto, tenor, chorus and orchestra, op.15 (lost) c.1909: “The Soldier’s Dream” for orchestra or voices and orchestra (lost) 1910: Symphonic Poem “In Memoriam”: 20 minutes + (Cameo Classics and Naxos cds) 1911-12: Concert Overture “Doctor Merryheart”: 16 minutes + (Cameo Classics, Naxos and Dutton cds) 1912: Herrick Songs for women’s chorus and orchestra + (two on Cameo Classics cd) 1913: Ballad “Pilgrimage -

London Philharmonic ORCHESTRA and Choir DVOŘÁK STABAT MATER, Op

DVOŘÁK STABAT MATER NEEME JÄRVI conductor JAniCE WATSON soprano DAGMAR PECKOVÁ mezzo soprano PETER AUTY tenor PETER ROSE bass LOndON PHILHARMOniC ORCHESTRA and CHOir DVOŘÁK STABAT MATER, OP. 58 Dvořák made a (now lost) setting of the Mass as a student The Stabat Mater sequence, of 13th-century Franciscan origin, exercise; but apart from that his first sacred work was his begins as a description of the Virgin Mary at the foot of the Stabat Mater, a setting of the mediaeval Latin prayer to Cross, and turns into a prayer to her for her intercession. the bereaved mother of the crucified Christ. It was drafted Dvořák set it in its entirety, several times grouping a number between February and May 1876, apparently as a delayed of its three-line stanzas together to form a substantial self- reaction to the death of the Dvořáks’ daughter Josefa the contained movement, and repeating passages of text freely previous September, two days after her birth. Several other to give each movement a strong formal outline. His scoring projects intervened before Dvořák got down to the task of is for four soloists, four-part chorus and orchestra; the orchestrating the work, in October and November 1877 – by inclusion of a part for organ (originally harmonium) in the which time the couple had also lost their second daughter, fourth movement suggests that he expected the instrument Růžena, who had died aged less than a year in August, and a to be used elsewhere in the work to support the chorus. month later their only son, the three-year-old Otakar. -

Journal46-1.Pdf

THE DELNUS SOCIETV Presrdent: ERIC FENBY,O.B.E.- Hon. R 4 M t**hvsl&nts: TUDRr, lloi. Loro Boonoy, x.B.r-.,tr.D Frlrx Apnaglmlx *OUIO GIEStt, M.tk., Ph.D. (Fotsldcr Member) Sn Cnrnr.rs Gnovns. c.s.s. Stexnono Rouxlox, o.t.E., A.n,.cx. (non), Fo*{. G.t.H. Chairmau R.B.ileadows, Esq., 5, lYestbourneHouse, MountPark Roed, Hartow, Middleser. Treasurer: G.H.Parfitt, Esq., 31, Lynwood Grove, Orpington, Kent. BR6 0 BD. ' Secretary:M.l{alker, Esq., 22, Elmsleigh Avenue, Kenton, Harrow, Middlesex. HA3 8HZ Membershipof the Delius Society costs f3.00 per yeer. Half*ates for students. THEDELIUS SOCIETY JOURNAT Number{6 Edltor: Chrlstopher Redwood CONTENTS Editorial page 2 Delius as Conductor page 4 Delius and BBC Symphony Orchestra page 10 'Send for the girl Tubb!' page 23 Delius on record page 25 News from the Midlands gage 27 Editorial Address: 4 Tabor Grove, LONDON, SW194EB Telephone Nurnber:01-946 5952. The Delius Society Journal is published in January, April, July and October. Further copies are available frorn the above address at 15p each, plus postage. Material for the next issue should reach the Editor as early as possible, and not later than 31st March, 1975. hinled by.J.T,Blease,780,llanor Road North, Thancs Ditton, Suney. KT7 0Be EDITORIAL Once upon e tine there wts e gnonc end tre lived in Zuich, or Brussels, d Rome, ot lomcwhcre. And being a tidy-ainded gnome, or p€rheps just partial to cdcring his fcllory gnooes about, he de- creed that all piecec of p.p"t should herrcefqth be of eterdard size and, of counse, of e size qulte different fron anytbitt thst enyone had ever thought of using before. -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0110 Notes

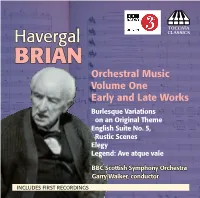

TOCCATA Havergal CLASSICS BRIAN Orchestral Music Volume One Early and Late Works ℗ Burlesque Variations on an Original Theme English Suite No. 5, Rustic Scenes Elegy Legend: Ave atque vale BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra Garry Walker, conductor INCLUDES FIRST RECORDINGS HAVERGAL BRIAN: EARLY AND LATE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC by Malcolm MacDonald Havergal Brian is best known for his copious output of 32 symphonies, but that series was not properly begun until the 1920s, when he was in his mid-forties. Before then he had composed several orchestral works in diferent genres – overtures, suites, symphonic poems, variation-sets and the like. hough aterwards his principal orchestral eforts were centred on the genre of the symphony, he continued to produce a range of smaller orchestral works of varying characters. he four works on this disc include what is probably Brian’s earliest surviving score for full orchestra, two mature but highly contrasted works from the 1950s, and the next-to-last work of any kind that he completed – a piece whose very title, Ave atque Vale, enshrines its nature as an epilogue and act of farewell. Burlesque Variations on an Original heme In a list of Brian’s early works (with opus numbers he would shortly abandon) which appeared in he Stafordshire Sentinel of 15 January 1907, against the opus number 3 stands the title ‘Burlesque Variations and Overture, for large orchestra’. he programme-notes for the London premieres of Brian’s English Suite No. 1 and For Valour in the Queen’s Hall Proms that season also mention ‘a set of Burlesque Variations’ among Brian’s other orchestral works.