Black Lives Matter Resource Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Visionary Leadership Project 2003

National Visionary Leadership Project 2003 ACMA staff 2014 Anacostia Community Museum Archives 1901 Fort Place, SE Washington, D.C. 20020 [email protected] http://www.anacostia.si.edu/Collections/ArchiveCollection Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 National Visionary Leadership Project 2003 ACMA.09-005 Collection Overview Repository: Anacostia Community Museum Archives Title: National Visionary Leadership Project 2003 Identifier: ACMA.09-005 Date: June 4, 2003 Creator: National Visionary Leadership Project Extent: 0.25 Linear feet (1 box) 5 Video recordings (5 VHS 1/2" video recordings) Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Co-founded in 2001 by Camille O. Cosby, Ed.D. and Renee Poussaint, The National Visionary Leadership Project (NVLP), a nonprofit, tax-exempt organization, unites generations to create tomorrow's leaders by recording, preserving, and distributing through various media, the wisdom of extraordinary -

Evolution of a Community: 1972 Exhibition Records

Evolution of a Community: 1972 Exhibition Records ACMA.M03-040 Kendra Jae Funding for partial processing of the collection was supported by a grant from the Smithsonian Institution's Collections Care and Preservation Fund (CCPF). 2017 July Anacostia Community Museum Archives 1901 Fort Place, SE Washington, D.C. 20020 [email protected] http://www.anacostia.si.edu/Collections/ArchiveCollection Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Exhibit Records, 1970-1972, undated...................................................... 4 Series 2: Oral History of Anacostia Project Files, 1970-1974, undated.................... 5 Series 3: Neighborhood Background Research Files, 1898-1988, -

Black Lives Matter at School Washington History Resources

Black Lives Matter Resource Guide This Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action Washington History Resource Guide is a curated list of content from Washington History including: A special issue released Fall 2020, “Meeting the Moment” came together in the summer of 2020 as a response to the global pandemic and ongoing Black Lives Matter protests. Profiles of famous as well as less well-known Black women and men who have made their mark on Washington, D.C.; Articles addressing political and social issues affecting the lives of Black women and men in Washington, D.C., from its founding to the near-present; Pieces highlighting the impact of local Black women and men on the arts, business, culture and politics of Washington, D.C. Teachable Moments – short articles designed for classroom use that take a single local primary source and explore its historical context with DCPS curricular needs in mind; and An annotated bibliography relating to a little-known experiment in community policing that took place in Washington, D.C. between 1968 and 1973. Last updated January 2021 Contents Washington History in the Classroom ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Selected profiles ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Dorcas Allen ...................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum

Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum 1 Rufus Mayfield and members of Youth Pride, Inc., August 7, 1967 Rufus “Catfish” Mayfield (pointing) employed some 900 African American youngsters to clean up the neighborhoods where they lived. Associated Press Image Archives 2 The exhibition Twelve Years that Twelve Years examines the rapidly changing racial, Shook and Shaped Washington: political, cultural, and built landscapes of this 1963-1975 offers an exciting period. Washington experienced the destruction and opportunity to continue the work reconstruction of whole neighborhoods, developed new of documentation of urban public and private institutions, cultivated a rise in black community long undertaken by leadership, and took steps toward home rule. Beyond the this museum. Established in exhibition narrative, Washingtonian voices provide first 1967 and located East of the hand experiences about local issues, efforts to organize, Anacostia River, the Anacostia and the results of their activism. Community Museum’s founding Today, our city is once again amid radical change. staff were led by a group of Cranes dot the skyline and development is transforming local community organizers. neighborhoods. New residents are joining long- Their main effort was to established resident in our neighborhoods. Many engage and empower diverse Photograph by Susana A. Raab, Anacostia Community Museum questions present themselves: How will development constituencies to examine benefit local communities? How will our neighborhoods local history and enter into public dialogue about contemporary remain home to people in every level of the economic issues. People and populations around the museum shaped the spectrum? How will the unique home-grown culture of entire mission, its approach to community engagement, and neighborhoods be preserved? many of its exhibitions. -

20Th Century Black Women's Struggle for Empowerment in a White Supremacist Educational System: Tribute to Early Women Educators

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Information and Materials from the Women's and Gender Studies Program Women's and Gender Studies Program 2005 20th Century Black Women's Struggle for Empowerment in a White Supremacist Educational System: Tribute to Early Women Educators Safoura Boukari Western Illinois University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/wgsprogram Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Boukari, Safoura, "20th Century Black Women's Struggle for Empowerment in a White Supremacist Educational System: Tribute to Early Women Educators" (2005). Information and Materials from the Women's and Gender Studies Program. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/wgsprogram/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Women's and Gender Studies Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Information and Materials from the Women's and Gender Studies Program by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Manuscript; copyright 2005(?), S. Boukari. Used by permission. 20TH CENTURY BLACK WOMEN'S STRUGGLE FOR EMPOWERMENT IN A WHITE SUPREMACIST EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM: TRIBUTE TO EARLY WOMEN EDUCATORS by Safoura Boukari INTRODUCTION The goal in this work is to provide a brief overview of the development of Black women‟s education throughout American history and based on some pertinent literatures that highlight not only the tradition of struggle pervasive in people of African Descent lives. In the framework of the historical background, three examples will be used to illustrate women's creative enterprise and contributions to the education of African American children, and overall racial uplift. -

Ruffins-Book.Pdf

Mythos. Memory. and History 507 CHAPTER 17 tory within the United States. There were both Native American and occasional European slaves at some points in American history, but slavery was an overwhelmingly African American experience. 2 That enslavement has fueled a powerful debate over the fundamental civil rights and appropriate governmental relationships laid out in docu Mythos, Memory, and ments such as the Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution, and the Constitution's Bill of Rights, to name only the History: African American most important. While conflict among ethnic groups and classes may characterize many aspects of American history, the Civil War had to be Preservation Efforts. , fought to resolve the issues relevant to Afro-Americans. Moreover, no 1820-1990 other ethnic group has been victimized by state constitutional amend ments denying them the right to vote and to share public facilities, as were African American people in the late-nineteenth-century South. FATH DAVIS RUFFINS While discrimination existed within many areas of American life against certain religious groups and people of foreign origins, at the same time segregation laws were formally enacted in many states for the specific purpose of controlling the social and political access and economic opportunities of one ethnic group: African Americans. Fur n 1968 a major television network aired thermore, the modern civil rights movement, which changed Ameri an extraordinarily popular documentary can life and has proven inspirational to activists around the world, entitled Black History: Lost, Stolen, or was initiated and led by African Americans. In these ways (and in IStrayed? Narrated by Bill Cosby, this others too detailed to mention) the history of Black people is deeply program sought to show the public the state of historical research and intertwined with the more general history of this country. -

Barry Farm Dwellings Other Names/Site Number N/A

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Barry Farm Dwellings other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number not for publication 1100-1371 Stevens Road SE; 2677-2687 Wade Road SE; 2652 Firth Sterling Avenue SE city or town Washington DC vicinity state DC code DC county N/A code 001 zip code 20011 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Signature of certifying official/Title Date State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

These Separate Schools: Black Politics and Education in Washington, D.C., 1900-1930

These Separate Schools: Black Politics and Education in Washington, D.C., 1900-1930 By Rachel Deborah Bernard A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Waldo Martin, Chair Professor Mark Brilliant Professor Malcolm Feeley Spring 2012 Abstract These Separate Schools: Black Politics and Education in Washington, D.C., 1900-1930 by Rachel Deborah Bernard Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Waldo Martin, Chair “These Separate Schools: Black Politics and Education in Washington, D.C., 1900-1930,” chronicles the efforts of black Washingtonians to achieve equitable public funding and administrative autonomy in their public schools and at Howard University. This project argues that over the course of the early twentieth century, black Washingtonians came to understand their two-pronged goals of administrative autonomy and equitable allocation of resources in both their public schools and at Howard in terms of civil rights. At the turn of the twentieth century, many African Americans in Washington defended their educational institutions as venues for individually demonstrating their own good citizenship and respectability, in other words as means to social and economic uplift. By the 1910s and 1920s, however, they spoke about equal educational opportunity as a civil right, guaranteed to all citizens by the Constitution. Also, while these struggles for educational equality began in the public schools, they were soon taken up by leaders at Howard University and its law school. In addition to educational equality, administrative autonomy was another key part of black Washingtonians’ rights agenda. -

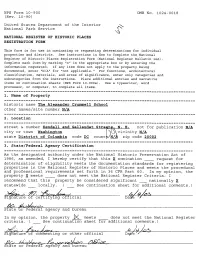

Nationally X Statewide Locally

NFS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Vs NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts . See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A) . Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box. or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a) . Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1 . Name of Property historic name The Alexander Crummell School other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number Kendall and Gallaudet Streets,/ 1 \\ N. ©. E. ©. not for publication N/A city or town Washington j ~Y\J\ vicinity N/A state District of Columbia code DC county/N/A zip code 20002 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Anna J. Cooper: a Voice from the South Exhibition Records

Anna J. Cooper: a voice from the South exhibition records Carrie Gehrer 2011 Anacostia Community Museum Archives 1901 Fort Place, SE Washington, D.C. 20020 [email protected] http://www.anacostia.si.edu/Collections/ArchiveCollection Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Series ACMA AV03-029: Anna J. Cooper: a voice from the South audiovisual records, 1981-1983 (bulk 1981-1981)...................................................................... 3 Anna J. Cooper: a voice from the South exhibition records ACMA.03-029 Collection Overview Repository: Anacostia Community Museum Archives Title: Anna J. Cooper: a voice from the South exhibition records Identifier: ACMA.03-029 Date: 1981-02 - 1982-09 Creator: Smithsonian Institution. Anacostia Community Museum Extent: 11.38 Linear feet (23 boxes) Language: English . Summary: An exhibition on Anna J. Cooper, Washington D. C. educator and author. It was organized by the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum and held there from February 1981 to September 1982. Louise Daniel Hutchinson served as curator. These records document -

Nationally X Statewide Locally

NFS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Vs NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts . See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A) . Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box. or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a) . Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1 . Name of Property historic name The Alexander Crummell School other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number Kendall and Gallaudet Streets,/ 1 \\ N. ©. E. ©. not for publication N/A city or town Washington j ~Y\J\ vicinity N/A state District of Columbia code DC county/N/A zip code 20002 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Fifty Essential Washington DC History Books (2011)

H-DC Fifty Essential Washington DC History Books (2011) Page published by Matthew Gilmore on Monday, August 11, 2014 50 Essential Washington DC History Books [2011] Compiled by DC Public Library Washingtoniana Division and the DC Center for the Book. The Jews of Washington, D.C. : a communal history anthology / edited by David Altshuler. 1st ed. [Washington, D.C.] : Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington ; Chappaqua, N.Y. : Rossel Books, c1985. Barras, Jonetta Rose. The last of the Black emperors : the hollow comeback of Marion Barry in the new age of Black leaders / Jonetta Rose Barras ; photos by Darrow Montgomery. Baltimore, Md. : Bancroft Press, c1998. Barber, Lucy G. (Lucy Grace), 1964- Marching on Washington : the forging of an American political tradition / Lucy G. Barber. Berkeley : University of California Press, c2002. Bergheim, Laura, 1962- The Washington historical atlas : who did what when and where in the nation's capital / Laura Bergheim. Rockville, MD : Woodbine House, 1992. Borchert, James, 1941- Alley life in Washington : family, community, religion, and folklife in the city, 1850-1970 / James Borchert. Urbana : University of Illinois Press, c1980. Bowling, Kenneth R. The creation of Washington, D.C. : the idea and location of the American capital / Kenneth R. Bowling. Fairfax, Va. : George Mason University Press ; Lanham, MD : Distributed by arrangement with University Pub. Associates, c1991. Brown, Letitia Woods. Free Negroes in the District of Columbia, 1790-1846. New York, Oxford University Press, 1972. Bryan, Wilhelmus Bogart. A history of the national capital from its foundation through the period of the adoption of the organic act, New York, The Macmillan company, 1914-16 Caplan, Marvin Harold.- Farther along : a civil rights memoir/ Marvin Caplan.