Communities Fragmented in Reconstruction After the Gujarat Earthquake of 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

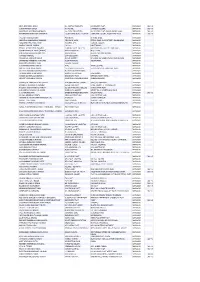

List of Approved Registered Graduates of Commerce Faculty 2017, Bhuj Taluka

LIST OF APPROVED REGISTERED GRADUATES OF COMMERCE FACULTY 2017, BHUJ TALUKA Sr. No. Name Address Taluka Reg No Challan No ACHARYA MALHAR DWIDHAMESHWAR BHUJ 992 1 PRAFULBHAI COLONY, BHUJ ACHARYA NANDISH 366/B BHUJ 798 BIMALKUMAR ,"NADIGRAM",ODHAV VILL RAW HOUSING, 2 AIYA NAGAR, MUNDRA ROAD,BHUJ,7567569745 ACHARYA RAHUL JUNI RAWALVADI P.L.- BHUJ 440 3 CHANDULAL 270,BHUJ, 814001211 AHALAPARA AT-149-152/2, ODHAV BHUJ 824 DULARI ASHOKBHAI EVENUE, MUNDRA 4 RELOCATION SITE,BHUJ AHALPARA DULARI 149, MUNDRA BHUJ 1055 5 ASHOKBHAI RELOCATION SITE, BHUJ. AHIR MOHINI 72, NRNARAYAN BHUJ 528 GOPALBHAI NAGAR, NR CHABUTRA CHOWK, GARBI CHOWK 6 JUNAVAS, MADHAPAR BHUJ, 9913838887 AHIR SHIVJI GOPAL 24, SHAKTI NAGAR-2, BHUJ 1099 BEHIND SORTHIYA 7 SAMAJWADI,JUNAVAS, MADHPAPAR, BHUJ, 9979980151 AJANI NAYAN SURAL BHIT ROAD, BHUJ 429 8 VASANTLAL MARKET YARD, BHUJ. 8140091211 AJANI VRAJNI JYUBELI HOSPITAL BHUJ 961 VASANTBHAI STREET-1, HATHISTHAN 9 SALA , BHUJ,8511312641 AKHANI POOJABEN 101, AIYA NAGAR, BHUJ 344 NIRANJANBHAI JUNA VAS, MADHAPAR, 10 TALUKA – BHUJ. 9725086947 AMRANI BHAKTI HOUSE NO:6, ANAND BHUJ 1402 KISHANCHAND BHAVAN, VRUNDAVAN PARK SOCIETY,OLD 11 RAILWAY STATION, BHUJ ANTANI CHIRAG 48/53-6, YOGIRAJ PARK BHUJ 580 SIRISHBHAI ,OPP ST WORKSHOP, 12 SANSKAR NAGAR,BHUJ, 9879292898 ANTANI HARASHAL 48-53/6, YOGIRAJ PARK, BHUJ 1343 SHIRISHBHAI OPP. ST WORKSHOP, 13 SANSKAR NAGAR, BHUJ ANTANI HARSHAL 48/53-6, YOGIRAJ PARK, BHUJ 425 SHIRISHBHAI OPPOSITE ST WORK SHOP, SANSKAR NAGAR, 14 BHUJ. 9638553439 9825337877 ANTANI JIGNEY KARISHMA, SANSKAR BHUJ 1200 15 BHASKARBHAI NAGAR 33/A, NEAR ST WORKSHOP, BHUJ. ARODA JITENDRA 331/3 B SANKAR BHUJ 1439 16 KHUSHALCHAND TRECTOR,JUNAVAS MADHAPAR,BHUJ ARUNKUMAR ASHAPURA TOWN SHIP, BHUJ 1559 17 JAGDISHPRASHAD AIRPORT ROAD, BHUJ, H. -

Compounding Injustice: India

INDIA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) – July 2003 Afsara, a Muslim woman in her forties, clutches a photo of family members killed in the February-March 2002 communal violence in Gujarat. Five of her close family members were murdered, including her daughter. Afsara’s two remaining children survived but suffered serious burn injuries. Afsara filed a complaint with the police but believes that the police released those that she identified, along with many others. Like thousands of others in Gujarat she has little faith in getting justice and has few resources with which to rebuild her life. ©2003 Smita Narula/Human Rights Watch COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: THE GOVERNMENT’S FAILURE TO REDRESS MASSACRES IN GUJARAT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] July 2003 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: The Government's Failure to Redress Massacres in Gujarat Table of Contents I. Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Impunity for Attacks Against Muslims............................................................................................................... -

MINA MEHANDRA MARU C/O CHETAK PRODUCTS 64

MINA MEHANDRA MARU C/o CHETAK PRODUCTS 64, DIGVIJAY PLOT, JAMNAGAR 361005 SUDHA MAHESH SAVLA H.K.HOUSE, 9,KAMDAR COLONY, JAMNAGAR 361006 POPATBHAI DEVJIBHAI KANJHARIA C/o. TYAG INDUSTRIES, 58, DIGVIJAY PLOT, UDYOG NAGAR ROAD, JAMNAGAR 361005 BHIKHABHAI BHANUBHAI KANJHARIA C/O.KHODIAR BRASS PRODUCT 2,KRUSHNA COLONY, 58,DIGVIJAY PLOT, JAMNAGAR 361005 VALLABH SAVJI SONAGRA PANAKHAN, IN VAKIL WADI, JAMNAGAR AMRUTLAL HANSRAJBHAI SONAGAR PIPARIA NI WADI, PETROL PUMP SLOPE STREET, GULABNAGAR JAMNAGAR JASODABEN FULCHAND SHAH PRADHNA APT., 1,OSWAL COLONY, JAMNAGAR RAKESH YASHPAL VADERA I-4/1280, RANJITNAGAR, JAMNAGAR BHARAT ODHAVJIBHAI BORANIA 1,SARDAR PATEL SOCIETY, OPP.MANGLAM, SARU SECTION ROAD, JAMNAGAR ISHANI DHIRAJLAL POPAT [MINOR] KALRAV HOSPITAL Nr.S.T.DEPO, JAMNAGAR SUSHILABEN LALJIBHAI SORATHIA BLOCK NO.1/4, G.I.D.C., Nr.HARIA SCHOOL, JAMNAGAR VIJYABEN AMBALAL LAXMI BUILDING K.V.ROAD, JAMNAGAR CHAMANLAL KESHAVJI NAKUM MAYUR SOCIETY, B/h.KRUSHNA NAGAR, PRAVIN DADHI WADI, JAMNAGAR JAMANBHAI MANJIBHAI CHANGANI 89,SHYAMNAGAR, INDIRA MARG, JAMNAGAR BHANUBEN MAGANLAL SHAH 4,OSWAL COLONY, JAMNAGAR ASHWIN HARIJIBHAI DHADIA A-64, JANTA SOCIETY, JAMNAGAR MULBAI DAYALJIBHAI MANGE C/o.KISHOR ENTERPRISE, 58,DIGVIJAY PLOT, HANUMAN TEKRI, JAMNAGAR UTTAM BHAGWANJIBHAI DUDHAIYA MU.ALIA BADA MAIN ROAD, JAMNAGAR JAYSUKH NARSHIBHAI NAKUM RANDAL MATA STREET, JUNA NAGNA, JAMNAGAR HARESH ISHWARLAL BHOJWANI 58,DIGVIJAY PLOT, OPP.ODHAVRAM HOTEL, JAMNAGAR HEMANT MADHABHAI MOLIYA JAYANTILAL CHANABHAI HOUS 5,KRUSHNANAGAR, JAMNAGAR CHANDULAL LIMBHABHAI BHESDADIA B-24,GOVERNMENT COLONY SARU-SECTION ROAD JAMNAGAR KANJIBHAI DEVSHIBHAI DEDANIA BEDESHVAR ROAD PATEL COLONY -5 "RANGOLI-PAN" JAMNAGAR KAUSHIK TRIBHOVANBHAI PANDYA BEHIND PANCHVATI COLLEGE AJANTA APARTMENT JAMNAGAR SUDHABEN JAYESHKUMAR AKBARI NANDANVAN SOCIETY STREET NO. -

C1-27072018-Section

TATA CHEMICALS LIMITED LIST OF OUTSTANDING WARRANTS AS ON 27-08-2018. Sr. No. First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio / BENACC Amount 1 A RADHA LAXMI 106/1, THOMSAN RAOD, RAILWAY QTRS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI DELHI 110002 00C11204470000012140 242.00 2 A T SRIDHAR 248 VIKAS KUNJ VIKASPURI NEW DELHI 110018 0000000000C1A0123021 2,200.00 3 A N PAREEKH 28 GREATER KAILASH ENCLAVE-I NEW DELHI 110048 0000000000C1A0123702 1,628.00 4 A K THAPAR C/O THAPAR ISPAT LTD B-47 PHASE VII FOCAL POINT LUDHIANA NR CONTAINER FRT STN 141010 0000000000C1A0035110 1,760.00 5 A S OSAHAN 545 BASANT AVENUE AMRITSAR 143001 0000000000C1A0035260 1,210.00 6 A K AGARWAL P T C P LTD AISHBAGH LUCKNOW 226004 0000000000C1A0035071 1,760.00 7 A R BHANDARI 49 VIDYUT ABHIYANTA COLONY MALVIYA NAGAR JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302017 0000IN30001110438445 2,750.00 8 A Y SAWANT 20 SHIVNAGAR SOCIETY GHATLODIA AHMEDABAD 380061 0000000000C1A0054845 22.00 9 A ROSALIND MARITA 505, BHASKARA T.I.F.R.HSG.COMPLEX HOMI BHABHA ROAD BOMBAY 400005 0000000000C1A0035242 1,760.00 10 A G DESHPANDE 9/146, SHREE PARLESHWAR SOC., SHANHAJI RAJE MARG., VILE PARLE EAST, MUMBAI 400020 0000000000C1A0115029 550.00 11 A P PARAMESHWARAN 91/0086 21/276, TATA BLDG. SION EAST MUMBAI 400022 0000000000C1A0025898 15,136.00 12 A D KODLIKAR BLDG NO 58 R NO 1861 NEHRU NAGAR KURLA EAST MUMBAI 400024 0000000000C1A0112842 2,200.00 13 A RSEGU ALAUDEEN C 204 ASHISH TIRUPATI APTS B DESAI ROAD BOMBAY 400026 0000000000C1A0054466 3,520.00 14 A K DINESH 204 ST THOMAS SQUARE DIWANMAN NAVYUG NAGAR VASAI WEST MAHARASHTRA THANA -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Ager (Hindu traditions) in India Ahmadi in India Population: 14,000 Population: 73,000 World Popl: 15,100 World Popl: 151,500 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 3 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - other Main Language: Kannada Main Language: Urdu Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Asma Mirza "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Ansari in India Arora (Hindu traditions) in India Population: 10,700,000 Population: 4,085,000 World Popl: 14,792,500 World Popl: 4,109,600 Total Countries: 6 Total Countries: 3 People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - Ansari People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other Main Language: Urdu Main Language: Hindi Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Biswarup Ganguly Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Arora (Sikh traditions) in India Badhai (Hindu traditions) -

The Structure of Indian Society: Then And

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 The Structure of Indian Society Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 ii The Structure of Indian Society Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 The Structure of Indian Society Then and Now A. M. Shah LONDON NEW YORK NEW DELHI Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 First published 2010 by Routledge 912 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Transferred to Digital Printing 2010 © 2010 A. M. Shah Typeset by Star Compugraphics Private Limited D–156, Second Floor Sector 7, Noida 201 301 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-415-58622-1 Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 To the memory of Purushottam kaka scholar, educator, reformer Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 vi The Structure of Indian Society Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 Contents Glossary ix Acknowledgements xiii Introduction 1 1. -

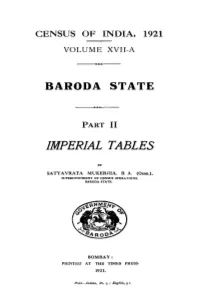

Baroda State, Imperial Tables, Part II, Vol-XVII-A

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1921 VOLUME XVII-A BARODA STATE PART II IMPERIAL TABLES BY SATYAVRATA MUKERJEA, B. A. (Oxon.). SUPBRINTENDENT OF CBNSUS OPBRATIONS, BARODA STATE. BOMBAY; PRINTED AT THE TIMES PRESS. 1921. PriCe-Indian, Rs. 9 .. Eng-lisk, 9 s. TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE TA.BLE I.-Area. Houses and Population .. 1 II.-Variation in Population since 1872 3 III.-Towns and Villages Classified by Population 5 " IV.-Towns Classified by Population. with Variation since 1872 .. 7 V.-Towns Arranged Territorially with Population by Religion " 9 VI.-Religion " 13 VII.-Age, Sex and Civil Condition- \ Part A-State Summary .. 16 •• B--Details for Divisions 22 " C-Details for the City of Baroda 28 VIII.-Education by Religion and Age- .. Part A-State Summary 32 " B-Details for Divisions 34 " C-Details for the City of Baroda 37 IX.-Education by Selected Castes, Tribes or Races ~g " X.-Language 43 XI.-Birth-Place 47 " XII.-Infirmities- Part I.-Distribution by A.ge 54 " II.-Distribution by Divisions 54 XII-A.-Infirmities by Selected Castes, Tribes or Races 55 " XIlL-Caste, Tribe, Race or Nationality- .. Part A-Hindu, .Jain, Animist and Hindu Arya 58 " B-Musalman 62 XIV.-Civil Condition by Age for Selected Castes 63 " .. XV.-Christians by Sect and Race 71 .. XVI.-Europeans and Anglo-Indians by Race and Age 75 XVII.-Occupation or Means of Livelihood 77 " .. XVIIL-Subsidiary Occupations of Agriculturists 99 Actual Workers only (1) Rent Receivers 100 (2) Rent Payers 100 (3) Agricultural Labourers 102 XIX.-Showing for certain Mixed Occupations the Number of Persons who " returned each as their (a) principal and (b) subsidiary Means of Livelihood 105 XX.-Distribution by Religion of Workers and Dependents in Different " Occupations 107 XXI.-Occupation by Selected Castes, Tribes or Races 113 " XXII.-Industrial Sta.tistics- " Part I-Etate Summary 124 " II-Distribution by Divisions 127 " III-Industrial Establishments classified according to the class of Owners and Managers . -

S. No. Institute Name State Last Name First Name Programme Course 1

S. No. Institute Name State Last Name First Name Programme Course 1 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat RAJAVADA ASMABANU ENGINEERING AND ENGINEERING EDUCATION FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 2 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat JADAV ARVINDKUMA ENGINEERING AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF R TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 3 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat PATEL HARSHITKUM ENGINEERING AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE AND FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF AR TECHNOLOGY ENGINEERING INSTITUTIONS 4 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat TANNA DUSHYANT ENGINEERING AND ENGINEERING EDUCATION FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 5 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat PADIA NOOTAN MCA MASTERS IN COMPUTER FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF APPLICATIONS INSTITUTIONS 6 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat RAITHATHA SAVAN MCA MASTERS IN COMPUTER FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF APPLICATIONS INSTITUTIONS 7 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat DAVE MALAY ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 8 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat SINGH KARISHMA ENGINEERING AND ENGINEERING EDUCATION FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 9 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat CHAVADA SUJIT ENGINEERING AND ELECTRONICS AND FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF TECHNOLOGY COMMUNICATIONS ENGINEERING INSTITUTIONS 10 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat ROY MALINI ENGINEERING AND CIVIL ENGINEERING FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF CHOUDHURY TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 11 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat VYAS CHANDRESHK ENGINEERING AND MECHANICAL ENGINEERING FOUNDATION'S GROUP OF UMAR TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTIONS 12 MARWADI EDUCATION Gujarat TRIVEDI RINKY MANAGEMENT BUSINESS MANAGEMENT -

Mandatory Disclosure

Mandatory disclosure Mandatory disclosure updated on: 13-09-2021 1. AICTE File No : Central/1-9319115173/EOA Date & Period of last : 25-June-2021 approval 2. Name of The Institute : GIDC Degree Engineering College Address of The Institute : Block No.997, Village Abrama, Tal. Jalalpore, Dist. Navsari Pin Code : 396406 State : Gujarat Phone Number With STD : (02637) 229040/41 Code Longitude & Latitude : 72o54’32” N; 20 o51’03” E Fax No. with STD code : (02637) 229041 College Time : 8.30 AM to 3.45 PM Office Hours at the College 8.45 AM to 4.15 PM Email ID : [email protected] Website : www.gdec.in College Fees : 25,000/- Per Year (W.E.F. from A.Y. 2020-21) Nearest Railway Station: Amalsad 05 KM from the campus Nearest Airport : Surat 55 KM from the campus Type of Institution : Public Private Partnership Category (1) of the : Non-Minority Institution Category (2) of the : Co-Ed Institution 3. Name of the Organization : GIDC Education Society running the Institution Type of the Organization : Society Address of the : Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation (GIDC). Organization Sector – 11, Udyog Bhavan, Block No. 3,4 & 5 Ghandhinagar -382017 Registered with: Under Society Registration Act 1960 Registration No. and Date : GUJ/1769/GANDHINAGAR dated 14.07.2010 Website of the : www.gidc.gov.in Organization 4. Name of the Affiliating : Gujarat Technological University, Chandkheda University Address of University : Nr. Campus of Vishwakarma Government Engineering College, Sabarmati –Koba Highway, Chankheda, Ahmadabad, Gujarat,Ph-07923267500 Website : www.gtu.ac.in Latest Affiliation Period : 2021-22 5. Name of Principal : Dr. -

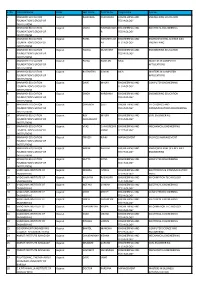

General General OR Financial SP BM (Business ROLL Principles of Fundamental English English (Operatio Sports & Sr.No

General General OR Financial SP BM (Business ROLL Principles of Fundamental English English (Operatio Sports & Sr.No. STUDENTS NAME CC A/C-2 Accounting- (Secretarial Management Environm NO. Economics-2 s of (English (Gujarati n Practice 2 Practice) ) ent Marketing Medium) Medium) Research) 1 ADANI KHUSHI SHAILESHKUMAR 1 38 48 48 44 46 - 38 44 - - 76 88 2 ASARI AKANKSHABEN MATHURBHAI 10 12 42 40 24 46 - 38 - - 12 78 82 3 DESAI DHRUV BHALABHAI 100 ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT 4 AAGJA DARSHANA SANJAYBHAI 1001 28 34 46 40 - 36 42 32 - - 66 80 5 ACHARYA UTSAV DEVANAND 1002 20 30 ABSENT 22 ABSENT ABSENT 16 ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT 50 ABSENT 6 AGRAWAL MANSI BHARATBHAI 1003 28 44 42 46 - 40 44 ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT 78 80 7 AHIR MIHIR JITENDRABHAI 1004 ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT 8 AOD SUNIL GUNVANTBHAI 1005 22 32 48 24 - 42 40 40 - - 76 76 9 APAVAT ABHILASHA LAXMANSINGH 1006 8 16 8 16 - 12 28 8 22 24 36 ABSENT 10 ARUNKAR YASH DATTATREY 1007 6 22 18 26 - 24 ABSENT 12 28 16 58 52 11 BALAT MAYANK MAHENDRABHAI 1009 ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT 12 DESAI GAUTAM MASHARUBHAI 101 38 48 50 48 46 - 44 46 - - 72 92 13 BALDANIYA JATIN JERAMBHAI 1010 30 34 46 40 - 36 42 - 34 - 66 78 14 BALDANIYA JAYDIP ANANDBHAI 1011 28 50 46 30 - 42 40 36 - - 78 88 15 BALDANIYA MANHAR JAGUBHAI 1012 28 44 36 30 - 40 ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT ABSENT 78 72 16 BAROT KRUPALI KANUBHAI 1015 18 30 40 24 26 - 28 24 - - 56 62 17 -

CSR Report 2.Pdf

CENTRE FOR EXCELLENCE IN CSR FACULTY OF SOCIAL WORK THE MAHARAJA SAYAJIRAO UNIVERSITY OF BARODA Aim: To emerge as the pioneering academic institute with repository of information and data spearheading CSR initiatives of corporate and industrial organizations of Western region. Objectives: 1. To prepare SOPs (standard operating procedures) on CSR guiding those undertaking research &intervention in the field. 2. To identify potential areas of intervention for CSR initiatives of interested industries by undertaking need assessment studies through primary or secondary data analysis. 3. To provide support to the member industries in its CSR practices through consultatancy services. 4. To undertake short term and long term training programs to enhance knowledge and skills of various stake holders and those interested in the mandate of CSR. 5. To evolve innovative CSR practices by undertaking field action programs in collaboration with a partner industries thereby showcasing different approaches to strive towards social development. 6. To document unique CSR practices/success stories carried out across the globe with particular reference to India. NATIONAL SEMINAR ON CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY: TRENDS AND OPPORTUNITIES 19-20th FEBRUARY, 2016 Organized By UGC - DSA Programme (Phase-III) and Centre for Excellence in Corporate Social Responsibility FACULTY OF SOCIAL WORK THE MAHARAJA SAYAJIRAO UNIVERSITY OF BARODA, VADODARA GUJARAT INDIA IN COLLABORATION AND SUPPORT WITH GUJARAT CSR AUTHORITY, GANDHINAGAR, GUJARAT ALKALIES & CHEMICALS LIMITED GUJARAT STATE FERTILIZER & CHEMICALS LIMITED Shri A.M Tiwari IAS MD- GSFC Ltd MESSAGE Corporate Social Responsibility is not a new concept in India. There have been companies in the country doing societal good, contributing for the welfare and development of people much before the inception of Companies Act, 2013.