Carnivore Damage Prevention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contact Details Number of Breeds Within FCI Groups List of Breeds

Contact details Last and First name of Judge Szczepańska-Korpetta Joanna Address 08-443 Sobienie Jeziory, Sobienie Kiełczewskie II - 17, Poland E-mail [email protected] Mobile (+48) 600 451 217 Home phone, Fax (+48) 22 839 65 84 ZKwP Branch Warszawa Languages Polish, German Number of breeds within FCI Groups FCI Group FCI group name Level 1 Sheepdogs and Cattle Dogs (except Swiss Cattle Dogs) (1/52) National 2 Pinscher and Schnauzer - Molossoid breeds - Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs International and other breeds (54/54) 3 Terriers (34/34) International 5 Spitz and primitive types (61/61) International 8 Retrievers - Flushing Dogs - Water Dogs (22/22) International 9 Companion and Toy Dogs (33/33) International List of breeds FCI Group Breed Level Sheepdogs and Cattle Dogs (except Swiss Cattle Dogs) 1 Polish Lowland Sheepdog (FCI - 251) National Pinscher and Schnauzer - Molossoid breeds - Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs and other breeds 2 Affenpinscher (FCI - 186) International 2 Alentejo Mastiff (FCI - 96) International 2 Appenzell Cattle Dog (FCI - 46) International 2 Atlas Mountain Dog - Aidi (FCI - 247) International 2 Austrian Pinscher (FCI - 64) International 2 Bernese Mountain Dog (FCI - 45) International 2 Bosnian and Herzegovinian - Croatian Shepherd Dog (FCI - 355) International 2 Boxer (FCI - 144) International 2 Broholmer (FCI - 315) International 2 Bulldog (FCI - 149) International 2 Bullmastiff (FCI - 157) International 2 Castro Laboreiro Dog (FCI - 170) International 2 Caucasian Shepherd Dog (FCI - 328) International 1 FCI Group -

BMC Genetics Biomed Central

BMC Genetics BioMed Central Research article Open Access MtDNA diversity among four Portuguese autochthonous dog breeds: a fine-scale characterisation Barbara van Asch1, Luísa Pereira1, Filipe Pereira1,4, Pedro Santa-Rita2, Manuela Lima3 and António Amorim*1,4 Address: 1Instituto de Patologia e Imunologia Molecular da Universidade do Porto (IPATIMUP), Portugal, 2CaniSemen Lda, Portugal, 3Centro de Investigação em Recursos Naturais (CIRN), Universidade dos Açores, Portugal and 4Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, Portugal Email: Barbara van Asch - [email protected]; Luísa Pereira - [email protected]; Filipe Pereira - [email protected]; Pedro Santa- Rita - [email protected]; Manuela Lima - [email protected]; António Amorim* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 22 June 2005 Received: 21 February 2005 Accepted: 22 June 2005 BMC Genetics 2005, 6:37 doi:10.1186/1471-2156-6-37 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2156/6/37 © 2005 Asch et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: The picture of dog mtDNA diversity, as obtained from geographically wide samplings but from a small number of individuals per region or breed, has revealed weak geographic correlation and high degree of haplotype sharing between very distant breeds. We aimed at a more detailed picture through extensive sampling (n = 143) of four Portuguese autochthonous breeds – Castro Laboreiro Dog, Serra da Estrela Mountain Dog, Portuguese Sheepdog and Azores Cattle Dog-and comparatively reanalysing published worldwide data. -

Contact Details Number of Breeds Within FCI Groups List of Breeds

Contact details Last and First name of Judge Kot Andrzej Address 42-600 Tarnowskie Góry, Torowa 58, Poland E-mail [email protected] Mobile (+48) 601 428 154 Home phone, Fax ZKwP Branch Bytom Languages Polish Number of breeds within FCI Groups FCI Group FCI group name Level 1 Sheepdogs and Cattle Dogs (except Swiss Cattle Dogs) (2/52) International 2 Pinscher and Schnauzer - Molossoid breeds - Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs International and other breeds (41/54) 6 Scenthounds and related breeds (2/77) International 10 Sighthounds (1/13) International List of breeds FCI Group Breed Level Sheepdogs and Cattle Dogs (except Swiss Cattle Dogs) 1 Polish Lowland Sheepdog (FCI - 251) International 1 Tatra Shepherd Dog (FCI - 252) International Pinscher and Schnauzer - Molossoid breeds - Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs and other breeds 2 Alentejo Mastiff (FCI - 96) International 2 Appenzell Cattle Dog (FCI - 46) International 2 Atlas Mountain Dog - Aidi (FCI - 247) International 2 Bernese Mountain Dog (FCI - 45) International 2 Bosnian and Herzegovinian - Croatian Shepherd Dog (FCI - 355) International 2 Broholmer (FCI - 315) International 2 Bulldog (FCI - 149) International 2 Bullmastiff (FCI - 157) International 2 Castro Laboreiro Dog (FCI - 170) International 2 Caucasian Shepherd Dog (FCI - 328) International 2 Central Asia Shepherd Dog (FCI - 335) International 2 Ciobanesc Romanesc de Bucovina (FCI - 357) International 2 Dogo Argentino (FCI - 292) International 2 Dogue de Bordeaux (FCI - 116) International 1 FCI Group Breed Level 2 Entlebuch -

AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL KENNEL COUNCIL LTD Judge

AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL KENNEL COUNCIL LTD GROUP 1 - TOYS Judge: Affenpinscher Bourbonnais Pointing Dog * Dachshund (Min. Long) Australian Silky Terrier Bracco Italiano Dachshund (Rabbit Long Bichon Frise Brittany Haired) * Bolognese * Chesapeake Bay Retriever Dachshund (Smooth) Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Clumber Spaniel Dachshund (Min. Smooth) Chihuahua (Long Coat) Cocker Spaniel Dachshund (Rabbit Smooth Chihuahua (Smooth Coat) Cocker Spaniel (American) Haired) * Chinese Crested Dog Curly Coated Retriever Dachshund (Wire) Continental Toy Spaniel Deutch Stichelhaar * Dachshund (Min. Wire) (Papillon) Drentsche Partridge Dog * Dachshund (Rabbit Wire Continental Toy Spaniel English Setter Haired) * (Phalene) * English Springer Spaniel Deerhound Coton De Tulear Field Spaniel Drever * Griffon Belge * Flat Coated Retriever Fawn Brittany Griffon * English Toy Terrier (Black & French Pointing Dog Gascogne Finnish Hound * Tan) Type * Finnish Spitz Griffon Bruxellois French Pointing Dog Pyrenean Foxhound Havanese Type * Gascon Saintongeois * Italian Greyhound French Spaniel * German Hound * Japanese Chin French Water Dog * Grand Basset Griffon King Charles Spaniel Frisian Pointing Dog * Vendeen Kromforhlander * Frisian Water Dog * Grand Griffon Vendeen * Lowchen German Shorthaired Pointer Great Anglo French-White & Maltese German Wirehaired Pointer Black Hound * Miniature Pinscher German Spaniel * Great Anglo-French Tri Colour Hound * Pekingese Golden Retriever Great Anglo-French White & Petit Brabancon * Gordon Setter Orange Hound * Pomeranian -

Castro Laboreiro Dog

THE ORIGIN OF THE CASTRO LABOREIRO DOG His origin still remains in the darkness ... but the presence of many Megalith in the area it's one prove of human presence since ancient times in those places. All the experts agree that all livestock guardian dogs are originally from Euro-Asia (the beginning of domestication) and they are large and powerful animals, used as predation control method. The Castro Laboreiro original dispersion zone was all the Laboreiro mountains. The Castro Laboreiro Livestock Guardian Dog is an autochthonal Portuguese breed , today can be found at Castro Laboreiro. Castro Laboreiro is, actually, the parish of Melgaço's counsel, belonging to the district of Viana do Castelo. The characteristics of the Castro Laboreiro mountain dog's not a herding dog, but a protective livestock canine, used against predators like wolf today. He become what he's, mainly, from the traditional lifestyle, typical of the population of that geographical area. There was seasonal migrations like tranzumansa "mudas" between the "Verandas" or "Brandas" and the "Inverneiras" (stimulated by "mother nature"). People move (to feed the Livestock) between one place in the winter to another place in the summer. These cyclic migrations "mudas", and always to the same places, were undoubtedly due to geographical limitation of the race. Note that was small migrations range areas, a few kms apart, "mini-tranzumansa"-"mudas". This lifestyle was fundamental to the breed, since it allowed the fixation of phenotypic traces and genetic ones, which evolved and were maintained by the exclusive motive of their good performance as a working dog. -

Livestock Guarding Dogs: Their Current Use World Wide

Copyright © 2001 by The Canid Specialist Group. The following is the established format for referencing this article: Rigg, R. 2001. Livestock guarding dogs: their current use world wide. IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group Occasional Paper No 1 [online] URL: http://www.canids.org/occasionalpapers/ Livestock guarding dogs: their current use world wide by Robin Rigg1* 1Department of Zoology, University of Aberdeen, Tillydrone Avenue, Aberdeen AB24 2TZ, UK. e-mail: [email protected] *Current address: Pribylina 150, 032 42, Slovakia. Robin Rigg is currently a postgraduate research student on the project Protection of Livestock and the Conservation of Large Carnivores in Slovakia, which he co-authored and launched in 2000. His research is focussed on the use of livestock guarding dogs to reduce predation on sheep and goats and a study of wolf and bear feeding ecology in the Western Carpathi ans. He has been working on a variety of other wolf and forest conservation projects in Slovakia since 1996. Livestock guarding dogs: their current use world wide Acknowledgements Thanks go to Dr. Claudio Sillero of the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) at Oxford University for his guidance on the initial outline and sources for this report as well as later comments on a draft; Dr. Martyn Gorman of the University of Aberdeen Zoology Department for advice and supervision; the staff of the Oxford University zoology libraries and Queen Elizabeth House library, the Balfour Library and Cambridge University Periodicals Library, University of Aberdeen -

Breed Specific Instructions (BSI) Regarding Exaggerations in Pedigree Dogs

By the Nordic Kennel Clubs 2014 Applicable from 2014 Breed Specific Instructions (BSI) regarding exaggerations in pedigree dogs DANSK KENNEL KLUB HUNDARÆKTARFÉLAG ÍSLANDS NORSK KENNEL KLUB SUOMEN KENNELLIITTO SVENSKA KENNELKLUBBEN Index Introduction .............................................................................................................................4 Application ..............................................................................................................................6 Basics for all dogs ...................................................................................................................8 Breed types ...........................................................................................................................10 FCI GROUP 1 Sheepdogs and Cattle Dogs ..............................................................................12 FCI GROUP 2 Pinscher and Schnauzer - Molossoïd Breeds - Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs ...14 FCI GROUP 3 Terriers .............................................................................................................19 FCI GROUP 4 Dachshunds ......................................................................................................21 FCI GROUP 5 Spitz and Primitive types ...................................................................................22 FCI GROUP 6 Scenthounds and Related Breeds ......................................................................24 FCI GROUP 7 Pointing Dogs ....................................................................................................26 -

Breed Specific Instructions (BSI) Regarding Exaggerations in Pedigree Dogs

By the Nordic Kennel Clubs 2014 Applicable from 2014 Breed Specific Instructions (BSI) regarding exaggerations in pedigree dogs DANSK KENNEL KLUB HUNDARÆKTARFÉLAG ÍSLANDS NORSK KENNEL KLUB SUOMEN KENNELLIITTO SVENSKA KENNELKLUBBEN Index Introduction .............................................................................................................................4 Application ..............................................................................................................................6 Basics for all dogs ...................................................................................................................8 Breed types ...........................................................................................................................10 FCI GROUP 1 Sheepdogs and Cattle Dogs ..............................................................................12 FCI GROUP 2 Pinscher and Schnauzer - Molossoïd Breeds - Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs ...14 FCI GROUP 3 Terriers .............................................................................................................19 FCI GROUP 4 Dachshunds ......................................................................................................21 FCI GROUP 5 Spitz and Primitive types ...................................................................................22 FCI GROUP 6 Scenthounds and Related Breeds ......................................................................24 FCI GROUP 7 Pointing Dogs ....................................................................................................26 -

Canine Genetic Tests by Breeds

Date: 09.03.2015. CANINE GENETIC Animal Health Issue : 1. TESTS BY BREEDS Version: 2. Pages: 1/14 Breed Genetic test(s) Affenpinscher Malignant Hyperthermia; D Locus (Dilution locus) Afghan Hound Malignant Hyperthermia; D Locus (Dilution locus); Degenerative Myelopathy; Hyperuricosuria Malignant Hyperthermia; D Locus (Dilution locus); Canine Coat Length; Degenerative Airedale Terrier Myelopathy; Hyperuricosuria Akita-Inu Malignant Hyperthermia; D Locus (Dilution locus); Canine Coat Length Malignant Hyperthermia; D Locus (Dilution locus); Canine Coat Length; Degenerative Alaskan Klee Kai Myelopathy; Hyperuricosuria Malignant Hyperthermia; D Locus (Dilution locus); Canine Coat Length; Degenerative Alaskan Malamute Myelopathy; Hyperuricosuria Alpine Dachsbracke Malignant Hyperthermia; D Locus (Dilution locus) American Akita Malignant Hyperthermia; D Locus (Dilution locus); Canine Coat Length Hyperuricosuria; Malignant Hyperthermia; D Locus (Dilution locus); Neuronal Ceroid American Bulldog Lipofuscinosis; Degenerative Myelopathy Phosphofructokinase Deficiency; Malignant Hyperthermia; D Locus (Dilution locus); American Cocker Spaniel Progressive Retinal Atrophy (PRA) rod-cone degeneration (prcd); Degenerative Myelopathy; Hyperuricosuria; Exercise-induced Collapse Malignant Hyperthermia; D Locus (Dilution locus); Degenerative Myelopathy; Progressive American Eskimo Dog Retinal Atrophy (PRA) rod-cone degeneration (prcd); Hyperuricosuria; Primary Lens Luxation American Foxhound Malignant Hyperthermia; D Locus (Dilution locus) Malignant Hyperthermia; -

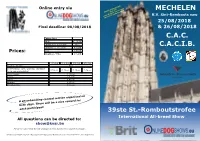

Mechelen C.A.C. C.A.C.I.B

Online entry via MECHELEN BREED SharSPECIALTIES Pei Royal Belgian Terrier Club K.V. Sint-Rombouts vzw Special St Hubertushond 25/08/2018 Final deadline: 08/08/2018 & 26/08/2018 Entry fees C.A.C. Adult € 10,00 Children < 12 years free C.A.C.I.B. Children < 18 years € 5,00 Prices: Dog € 5,00 Disabled / 60+ € 5,00 1st dog 2nd dog 3rd dog 4th dog couples, groups free intermediary, open, working, champion € 52,00 € 48,00 € 45,00 € 42,00 (only same proprietor) minor puppy € 30,00 puppy € 32,00 junior € 45,00 veteran € 35,00 showhandling € 10,00 A showhandling contest will be organised on both days. There will be a nice reward for each participant. 39ste St.-Romboutstrofee International All-breed Show All questions can be directed to: [email protected] Please be aware that the list of judges in this document is subject to change. Verantwoordelijke uitgever: Kynologenvereniging Sint-Rombouts vzw - Korte Dreef 5 - 2820 Rijmenam SATURDAY 25/08/2018 - GROUP 2 SUNDAY 26/08/2018 - GROUP 1 Mr. Bailey P.G. (UK): Deutscher Boxer Fawn/Brindle, Rottweiler Mr. Brechtold Peter (AU): Picardische Herdershond, Briard (Berger de Brie) Slate, Briard (Berger de Brie) Fawn/grey, Ciobanesc Romanesc Mioritic, Ciobanesc Romanesc Carpatin, Hvartski Ovcar -Kroatische Herder, Komondor, Polski Owczarek podhalanski - Tatra Sheperd Dog, Mrs. White Amanda (UK): Bullmastiff GERMAN SHEPHERD DOG, BELGIAN SHEPHERD DOG Groenendael, BELGIAN SHEPHERD DOG Laekenois, BELGIAN SHEPHERD DOG Malinois, BELGIAN SHEPHERD Mr. Bond John (IRL): Shar Pei, Dobberman Black/Brown, Miniature Pincher Zwergpinscher Stag red/red Brown/Black & tan, Austrian Pincher, DOG Tervueren, Ioujnorousskaïa Ovtcharka South Russian Sheperd Dog, CZECHOSLOVAKIAN WOLFDOG Affenpincher, Fila Brasileiro, Duitse Pincher Black/Black and tan, Central Asia Sheperd Dog (Sredneasiatskaïa Ovtcharka, Pyrenean Mr. -

Livestock Guarding Dogs: Their Current Use World Wide

Copyright © 2001 by The Canid Specialist Group. The following is the established format for referencing this article: Rigg, R. 2001. Livestock guarding dogs: their current use world wide. IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group Occasional Paper No 1 [online] URL: http://www.canids.org/occasionalpapers/ Livestock guarding dogs: their current use world wide by Robin Rigg1* 1Department of Zoology, University of Aberdeen, Tillydrone Avenue, Aberdeen AB24 2TZ, UK. e-mail: [email protected] *Current address: Pribylina 150, 032 42, Slovakia. Robin Rigg is currently a postgraduate research student on the project Protection of Livestock and the Conservation of Large Carnivores in Slovakia, which he co-authored and launched in 2000. His research is focussed on the use of livestock guarding dogs to reduce predation on sheep and goats and a study of wolf and bear feeding ecology in the Western Carpathi ans. He has been working on a variety of other wolf and forest conservation projects in Slovakia since 1996. Livestock guarding dogs: their current use world wide Acknowledgements Thanks go to Dr. Claudio Sillero of the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) at Oxford University for his guidance on the initial outline and sources for this report as well as later comments on a draft; Dr. Martyn Gorman of the University of Aberdeen Zoology Department for advice and supervision; the staff of the Oxford University zoology libraries and Queen Elizabeth House library, the Balfour Library and Cambridge University Periodicals Library, University of Aberdeen -

A Pedigree-Based Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA Diversity in a Dog Population on the Example of German Hovawarts

Arch. Anim. Breed., 58, 335–342, 2015 www.arch-anim-breed.net/58/335/2015/ Open Access doi:10.5194/aab-58-335-2015 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Archives Animal Breeding A pedigree-based analysis of mitochondrial DNA diversity in a dog population on the example of German Hovawarts S. Zielinska´ 1 and I. Głazewska˙ 2 1Department of Molecular Biology, University of Gdansk,´ Gdansk,´ Poland 2Department of Plant Taxonomy and Nature Conservation, University of Gdansk,´ Gdansk,´ Poland Correspondence to: I. Głazewska˙ ([email protected]) Received: 14 November 2014 – Revised: 12 July 2015 – Accepted: 13 July 2015 – Published: 13 August 2015 Abstract. The purpose of the article is to illustrate the use of pedigree analysis to evaluate mtDNA diversity in a selected population of pedigree dogs, to describe the paths of mtDNA inheritance and to estimate the spread of potential pedigree errors or mutations that occurred in different generations of ancestors. Hovawart, old German breed, was used as an example. The number and frequencies of mtDNA haplotypes were calculated based on numbers of dam lines and their representatives. The scale of potential errors in calculations that can result from pedigree errors or from new mutations in ancestors from the 5th or 10th ancestral generation was evaluated. The analysis included 368 breeding bitches from four German kennel organizations. The bitches represented three dam lines, with the Ho1, Ho2 and HoU mtDNA haplotypes. Significant differences in the frequency of the hap- lotypes in the population, from 0.27 to 73.37 %, and among kennel organizations and regions of the country were recorded.