Estuary General Eia Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Catalogue

Five Hundred Years of Fine, Fancy and Frivolous Bindings George bayntun Manvers Street • Bath • BA1 1JW • UK Tel: 01225 466000 • Fax: 01225 482122 Email: [email protected] www.georgebayntun.com BOUND BY BROCA 1. AINSWORTH (William Harrison). The Miser's Daughter: A Tale. 20 engraved plates by George Cruikshank. First Edition. Three volumes. 8vo. [198 x 120 x 66 mm]. vii, [i], 296 pp; iv, 291 pp; iv, 311 pp. Bound c.1900 by L. Broca (signed on the front endleaves) in half red goatskin, marbled paper sides, the spines divided into six panels with gilt compartments, lettered in the second and third and dated at the foot, the others tooled with a rose and leaves on a dotted background, marbled endleaves, top edges gilt. (The paper sides slightly rubbed). [ebc2209]. London: [by T. C. Savill for] Cunningham and Mortimer, 1842. £750 A fine copy in a very handsome binding. Lucien Broca was a Frenchman who came to London to work for Antoine Chatelin, and from 1876 to 1889 he was in partnership with Simon Kaufmann. From 1890 he appears under his own name in Shaftesbury Avenue, and in 1901 he was at Percy Street, calling himself an "Art Binder". He was recognised as a superb trade finisher, and Marianne Tidcombe has confirmed that he actually executed most of Sarah Prideaux's bindings from the mid-1890s. Circular leather bookplate of Alexander Lawson Duncan of Jordanstone House, Perthshire. STENCILLED CALF 2. AKENSIDE (Mark). The Poems. Fine mezzotint frontispiece portrait by Fisher after Pond. First Collected Edition. 4to. [300 x 240 x 42 mm]. -

261 Condamine Street, Manly Vale DESIGNED for the COASTAL URBAN MINDED VERDE APARTMENTS

261 condamine street, manly vale DESIGNED FOR THE COASTAL URBAN MINDED VERDE APARTMENTS THIS IS YOUR HOME. YOUR STORY. 5 6 VERDE APARTMENTS A MODERN COASTAL URBAN MASTERPIECE Simply stunning comes to mind when you appreciate the functionalist interiors, detailed finishes and fantastic use of space. Design is at front- of-mind with every Verde apartment, for its superb balance of indoor and outdoor living spaces and the sophisticated exterior of the buildings and alluring landscape to form a single, sensational address. The excellent Manly Vale location will be fuel for daily inspiration and the fortunate residents will indulge in their designer apartment, which will be constructed and completed to the highest quality. 8 VERDE APARTMENTS EXPERIENCE VERDE. EVERY DAY. Open planned and free flowing, every apartment enjoys privacy and access to its own outdoor retreat – sunlit courtyards or terraces. Choose from the selection of flexible single bedroom, one bedroom, and two bedroom apartments. While living areas and bedrooms merge with the inviting terraces, the elegant design continues with signature touches throughout. Kitchens are dressed with pared back white cupboards, Namoi River Stone benchtops and full appliances, with the option of solid natural bamboo flooring, light grey glass splashback and Smeg devices. The well-appointed bathrooms boast a smart design of matte white walls and Belga Charcoal tile flooring, with an option of a tile feature wall, semi frameless shower screen and divine Caroma ensemble. 9 10 3. ENJOY THE GREAT GREEN OUTDOORS. LIFE IS VIVID AT VERDE. 1. 2. 4. Manly Vale makes the most of its wondrous nature reserves and the array of recreational activities on offer. -

Aviation Historical Society of Australia

Aviation Historical Society OF Australia Registered in Australia for transmission by post as a periodical Moy - June 1968. ' A H,S * A,. Journal May-June 1968 The Conmonw'ealth Aircraft Corporation CA-15« By David Eyre The CA-15 vms the second single seat fighter designed and built in Australia for service in the Pacific Theatre of Operations^ the Boomerang being the firsto During the war^ a liAAF specification was in existence for a long-range^ medium altitude^ high performance fighter^ and the original intention was to develop the Boomerang by fitting a higher powered engine than the 1,200 hp Pratt and Whitney. However it was found that the basic. Boomerang fuselage would not take the extra weight of the larger engine without a considerable amount of redesign, and so this idea was discarded. A number of conferences were held between officials of the R/\iiF and CAC daring 1943 and 1944, and in 1945 the design of the CA=-15 was accepted to fill the above mentioned specificatioiio Work on the prototype coiumenced that year and the aircraft was rolled out earl57' in 1946, taxying tests commencing on February 12tho When seen at a distance, the average spotter might have confused the GA-^15 with the North American Mustang, wiiich was being built under licence by CAC as the CA-17. Compared with the Mustang, the GA-15 had a smaller wing span and increased lengtho One of the most obvious differences was the nine degree dihedral setting of the tailplane, and another being the airscoop for the chest position radiator. -

The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art

Dominican Scholar Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Liberal Arts and Education | Graduate Theses Student Scholarship May 2019 The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art Maura Wilson Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HUM.06 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Wilson, Maura, "The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art" (2019). Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Theses. 6. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HUM.06 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberal Arts and Education | Graduate Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This thesis, written under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor and approved by the department chair, has been presented to and accepted by the Master of Arts in Humanities Program in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts in Humanities. An electronic copy of of the original signature page is kept on file with the Archbishop Alemany Library. Maura Wilson Candidate Joan Baranow, PhD Program Chair Joan Baranow, PhD First Reader Sandra Chin, MA Second Reader This master's thesis is available at Dominican Scholar: https://scholar.dominican.edu/humanities- masters-theses/6 i The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art By Maura Wilson This thesis, written under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor and approved by the program chair, has been presented to an accepted by the Department of Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Humanities Dominican University of California San Rafael, CA May 2019 ii iii Copyright © Maura Wilson 2019. -

Download This PDF File

Illustrating Mobility: Networks of Visual Print Culture and the Periodical Contexts of Modern Australian Writing VICTORIA KUTTAINEN James Cook University The history of periodical illustration offers a rich example of the dynamic web of exchange in which local and globally distributed agents operated in partnership and competition. These relationships form the sort of print network Paul Eggert has characterised as being shaped by everyday exigencies and ‘practical workaday’ strategies to secure readerships and markets (19). In focussing on the history of periodical illustration in Australia, this essay seeks to show the operation of these localised and international links with reference to four case studies from the early twentieth century, to argue that illustrations offer significant but overlooked contexts for understanding the production and consumption of Australian texts.1 The illustration of works published in Australia occurred within a busy print culture that connected local readers to modern innovations and technology through transnational networks of literary and artistic mobility in the years also defined by the rise of cultural nationalism. The nationalist Bulletin (1880–1984) benefited from a newly restricted copyright scene, while also relying on imported technology and overseas talent. Despite attempts to extend the illustrated material of the Bulletin, the Lone Hand (1907–1921) could not keep pace with technologically superior productions arriving from overseas. The most graphically impressive modern Australian magazines, the Home (1920–1942) and the BP Magazine (1928–1942), invested significant energy and capital into placing illustrated Australian stories alongside commercial material and travel content in ways that complicate our understanding of the interwar period. One of the workaday practicalities of the global book trade which most influenced local Australian producers and consumers prior to the twentieth century was the lack of protection for international copyright. -

Low Culture in Sydney 1887-1914

Common Pleasures: Low Culture in Sydney 1887-1914 Susan Doyle Doctor of Philosophy 2006 CERTIFICATE OF AUTHORSHIP/ORIGINALITY I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for degree, nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledge. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Susan Doyle. Contents Preface and Acknowledgements ii Abstract vi Introduction 1 Part 1, The Pub 23 Chapter 1: The 1887 Intoxicating Drink Inquiry 24 Chapter 2: Lower-Class Drinking: Places and Practices 54 Chapter 3: Women and the Drink Question 82 Part 2, The Vaudeville Theatre 115 Chapter 4: 'Colour, Music, Light and Rhythm': Vaudeville in Sydney 116 Chapter 5: The Gallery Gods: 'Kicking up a Row in Olympus' 141 Chapter 6: “We’ve Got a Lodger and He’s Very Fond of Ma’: The Vaudeville Repertoire 162 Part 3, The Street 196 Chapter 7: Larrikin Days 197 Chapter 8: The Haymarket Swell: Larrikin Fashion 223 Chapter 9: Everyday Resistance: Larrikin Street Life 248 Conclusion 280 Bibliography 285 i Preface and Acknowledgements In Heterologies De Certeau writes: By a professional reflex, the historian refers any discourse to the socioeconomic or mental conditions that produced it. He needs to apply this kind of analysis to his own discourse in a manner that will make it pertinent to the elucidation of those forces that presently organise representations of the past. -

Opal Refund and Balance Transfer Policy Electronic Ticketing System Version 4.8

Opal Refund and Balance Transfer Policy Electronic Ticketing System Version 4.8 Opal Refund and Balance Transfer Policy Contents 1. Introduction 2. Definitions 3. Reloadable Opal Cards A. Refunds B. Balance Transfers C. Adjustments 4. Single Trip Tickets A. Refunds B. Transfers 5. Opal Top Up and Single Trip Ticket Machine Transactional Errors A. Reimbursements B. Transfers 6. Approved Payment Device (Contactless Payments) A. Reimbursements 7. Opal Digital Cards A. Refunds B. Reimbursements 8. Forms 2 1. Introduction This Opal Refund and Balance Transfer Policy: I. sets out the terms upon which we will provide refunds under the Opal Ticketing System for reloadable Opal Cards and Single Trip Tickets; II. describes the terms upon which we will transfer the balance of a reloadable Opal Card and the cost of a Faulty Single Trip Ticket to another Opal Card; III. describes the terms upon which we will issue adjustments to the Opal Balance of a reloadable Opal Card; IV. describes the terms upon which we will issue a reimbursement for a transactional error when an Opal Top Up and Single Trip Ticket machine is faulty or malfunctions; and V. describes the terms upon which we will issue a reimbursement for an error when a fare using the Opal Ticketing System is purchased using a Device for the Designated Services; VI. describes the terms upon which we will issue a reimbursement of the Reimbursable Amount for a Device Transactional Error for Approved Payment Devices and Opal Digital Cards; VII. describes the terms upon which we will provide refunds under the Opal Ticketing System for Opal Digital Cards; 2. -

Science, Fashion, Knowledge and Imagination: Shopfront Natural History in 19Th-Century Sydney

Science, Fashion, Knowledge and Imagination: Shopfront Natural History in 19th-Century Sydney ANNE COOTE isiting Sydney in 1845, a young French tourist, Eugène Delessert, was agreeably surprised by the advanced state of the town’s V commercial development and particularly impressed by the array of native birds on show in the Hunter Street establishment of the natural history dealer, John William Roach. During his time in this colonial capital Delessert, as he reported later, often enjoyed gazing at the brilliantly coloured plumage of the several hundred birds which fluttered among the shrubs inside Roach’s large aviary. The parrots and pigeons delighted him, but equally remarkable, he thought, was the lovely Regent Bower Bird, a study in velvet black and brilliant gold. Sydney dealers, Delessert informed his readers, had this bird for sale in quite large numbers.1 Sydney Journal Vol 4, No 1 (2013): 1–18 ISBN: 1835-0151 © UTSePress and the author Sydney Journal | Coote The existence of such a trade in native species, as Delessert would have understood, signalled that a good many people in this far-flung colonial outpost shared the cultural and intellectual engagement with natural history which was common in the metropole. Indeed, businesses like that of Roach with their novelty, noise and colour apparently found a ready market in mid-nineteenth century Sydney, with six trading for varying periods during the 1840s, and at least seven in each of the following two decades, although not all at the same time. This article examines the character of mid-nineteenth century shop-front natural history enterprise and considers its significance for the inhabitants of Sydney and its visitors. -

OECD Territorial Grids

BETTER POLICIES FOR BETTER LIVES DES POLITIQUES MEILLEURES POUR UNE VIE MEILLEURE OECD Territorial grids August 2021 OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities Contact: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Territorial level classification ...................................................................................................................... 3 Map sources ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Map symbols ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Disclaimers .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Australia / Australie ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Austria / Autriche ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium / Belgique ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Innovating Transport Across Australia

PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Innovating Transport across Australia Inquiry into automated mass transit House of Representatives Standing Committee on Infrastructure, Transport and Cities March 2019 CANBERRA © Commonwealth of Australia ISBN 978-1-76092-003-6 (Printed Version) ISBN 978-1-76092-004-3 (HTML Version) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. Contents Foreword .......................................................................................................................................... vii Members ............................................................................................................................................ xi Terms of Reference ......................................................................................................................... xiii Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... xv List of Recommendations .............................................................................................................. xix Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... xxv The Report 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. -

Knobbly the Pelican Saved by Team Effort

MidCoast Council Meet Local Legend Star Pet Updates Don Wright Bailey Forster Fortnightly Your local independent community newspaper distributed fortnightly to FREE Hallidays Point, Black Head, Tallwoods Village, Tuncurry, Forster Pacific Palms, Charlotte Bay, Smiths Lake, Coomba Park, Bungwahl and Seal Rocks. Wednesday 23rd June 2021 Owned and Loved by Locals Circulation 6000 N0.23 Knobbly the Pelican saved by team effort For the last decade, Knobbly the pelican, has made himself a resident of the Red Spot fish shop on Little Street in Forster. This might have something to do with his love of mullet! Last month, Tim Love (then Manager of Red Spot) noticed that poor Knobbly had a fishing line stuck in his throat. What happened next is an amazing chain of events that eventually resulted in a recovered Knobbly being released into the channel a few weeks later in front of all his rescuers. On that day, the 11th of May 2021, Tim saw at once that help was needed if Knobbly was to survive. He called the Sweet Pea Vet Clinic who gave him good advice on how to capture a pelican. Tim used a mullet to distract Knobbly while his colleague covered the pelican up with a sheet. Tim then scooped Knobbly up and took Below: Tim Love with Knobbly the Pelican. Above: Photo of Knobbly being released back to the channel at Forster by Kym Kilpatrick. During Knobbly’s him to the Vet Clinic down the road before and took him home to stay overnight in their stay of several contacting Kym Kilpatrick and Stan Bolden, outdoor shower at Hallidays Point. -

Mobile Crane Network

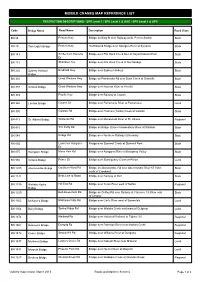

MOBILE CRANES MAP REFERENCE LIST RESTRICTION DESCRIPTIONS - SPV Level 1 / SPV Level 1 & UAC / SPV Level 1 & UPC Code Bridge Name Road Name Description Road Class BN 24 Princes Hwy Bridge on King St over Railway at St. Peter's Station State BN 29 Tom Ugly's Bridge Princes Hwy Northbound Bridge over George's River at Sylvania State BN 143 Sir Bertram Stevens Bridge over Flat Rock Creek No2 at Royal National Park State Dr BN 172 Stahallen Ave Bridge over Flat Rock Creek at Northbridge State BN 226 Sydney Harbour Bradfield Hwy Bridge over Sydney Harbour State Bridge BN 316 Great Western Hwy Bridge on Parramatta Rd over Duck Creek at Granville State BN 333 Victoria Bridge Great Western Hwy Bridge over Nepean River at Penrith State BN 339 Pacific Hwy Bridge over Railway at Cowan State BN 360 Lennox Bridge Church St Bridge over Parramatta River at Parramatta Local BN 390 Galston Rd Bridge over Pearces (Tunks) Creek at Galston State BN 413 St. Albans Bridge Wollombi Rd Bridge over Macdonald River at St. Albans Regional BN 415 The Putty Rd Bridge on Bridge St over Hawkesbury River at Windsor State BN 548 Bridge Rd Bridge over Northern Railway at Hornsby State BN 856 Lawrence Hargrave Bridge over Stanwell Creek at Stanwell Park State Dr BN 875 Hampden Bridge Moss Vale Rd Bridge over Kangaroo River at Kangaroo Valley State BN 965 Victoria Bridge Prince St Bridge over Stonequarry Creek at Picton Local BN 1015 Abercrombie Bridge Goulburn-Ilford Rd Bridge on Abercrombie Rd over Abercrombie River 67.16km State north of Crookwell BN 1141 Bells Line of