Joint Filmmakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Melanie Lynskey. Height 178 Cm

Actor Biography Melanie Lynskey. Height 178 cm Awards. 2001 New Zealand Film Awards - Nomination - Best Actress - Snakeskin 1994 New Zealand Film Awards - Winner - Best Actress - Heavenly Creatures Film. 2017 1 Mile to you Coach Rowan Dir. Leif Tilden (Lead) Prd. Scott William Alvarez, Tom Butterfield, Peter Holden, F. X. Vitolo Feature Film. 2017 The Changeover Kate Chant Changeover Films Limited Dir. Miranda Harcourt and Stuart McKenzie Prd. Emma Slade 2017 Sadie Rae Dir. Megan Griffiths (Lead) Prd. Megan Griffiths 2017 And Then I Go Janice Dir. Vince Grashaw Prd. Vince Grashaw 2017 I Don 't Feel At Home In This World Ruth Netflix Anymore Dir. Macon Blair Prd. Mette-Marie Kongsved, Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, Anish Savjani 2016 The Intervention Annie Burn Later Productions Dir. Clea DuVall 2016 The Great & The Small Margaret Cervidae Films Dir. Dusty Bias PO Box 78340, Grey Lynn, www.johnsonlaird.com Tel +64 9 376 0882 Auckland 1245, NewZealand. www.johnsonlaird.co.nz Fax +64 9 378 0881 Melanie Lynskey. Page 2 Feature continued... 2016 Folk Hero & Funny Guy Becky Spitfire Studios Dir. Jeff Grace 2016 Little Boxes Gina Kid Noir Productions Dir. Rob Meyer 2016 Rainbow Time Lindsay Duplass Brothers Productions Dir. Linas Phillips 2015 Digging for Fire Squiggy Garrett Motion Pictures Dir. Joe Swanberg 2014 We'll Never Have Paris Devon Bifrost Pictures Dir. Simon Helberg, Jocelyn Towne 2014 Goodbye to All That Annie Wall Epoch Films Dir. Angus MacLachlan Prd. Anne Carey, Mindy Goldberg 2014 Happy Christmas Kelly Lucky Coffee Productions Dir. Joe Swanberg 2014 Chu and Blossom Miss Shoemaker Baked Industries Dir. -

Welcome to the 44Th Annual Seattle International Film Festival!

BETH BARRETT SARAH WILKE Artistic Director Executive Director DEAR MEMBERS OF THE PRESS: Welcome to the 44th annual Seattle International Film Festival! We are so happy to have you join this year as a partner at the Festival. It's your work that helps bring filmmakers and audiences together around the powerful stories of film. We could never have become the SIFF we are today without the knowledge, skill, and passion you bring to your work. Our 2018 Media Guide is filled with all the pertinent information you'll need to navigate the next 25 days: media guidelines and contacts, film listings, forums, and events. Many of you are already familiar with SIFF's extensive Festival offerings. For those of you who are attending for the first time, we are here to help you discover the depth and range of our programming. The greater press community has always been an integral part of the Festival and we look forward to sharing with you all that SIFF has to offer over the Festival. Sincerely, SIFF.NET · 206.464.5830 · PRESS OFFICE 206.315.0690 · [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 . PRESS INFORMATION 5 . SIFF STAFF 10 . BOARD OF DIRECTORS 11 . ABOUT SIFF 12 . SIFF BY THE NUMBERS 13 . SIFF FACT SHEET 14 . EVENT SCHEDULE 18 . MEDIA GUIDELINES 19 . HOLD REVIEWS 23 . VENUES 24 . TICKETING 27 . FEATURE FILMS BY MOOD 39 . FEATURES BY COUNTRY/REGION 44 . TOPICS OF INTEREST 57 . AWARDS & COMPETITIONS 64 . 360/VR STORYTELLING 65 . EDUCATION 67 . SPECIAL GUESTS 69 . SPOTLIGHT PRESENTATIONS 70 . 2017 RECAP 73 . FESTIVAL 2017 HIGHLIGHTS 74 . -

Alien : Covenant

TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX présente Une production Scott Free/Brandywine Un film de Ridley Scott ALIEN : COVENANT Michael Fassbender Katherine Waterston Billy Crudup Danny McBride Demián Bichir Scénario : John Logan, Dante Harper Histoire : Jack Paglen, Michael Green Image : Dariusz Wolski Décors : Chris Seagers Costumes : Janty Yates Un film produit par Ridley Scott, Mark Huffam, Michael Schaefer, David Giler, Walter Hill Sortie nationale : 10 mai 2017 Durée : 2 h 02 Photos et dossier de presse sont téléchargeables sur : www.foxpresse.fr Site officiel : Distribution Presse film TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX Alexis RUBINOWICZ 241 boulevard Pereire Tél. : 01 58 05 57 90 75017 PARIS [email protected] Tél. : 01 58 05 57 00 Giulia GIE Tél. : 01 58 05 57 79/94 [email protected] 1 L’HISTOIRE Le vaisseau spatial Covenant est en route pour la lointaine planète Origae-6 afin d’y établir une colonie, un nouvel avant-poste pour l’humanité. À bord, tout est calme. L’équipage et les 2000 passagers sont en hypersommeil, et seul Walter, le synthétique, arpente les coursives. Mais lorsqu’une explosion stellaire détruit les capteurs d’énergie du vaisseau, les avaries et les pertes humaines sont énormes… Heureusement, les survivants découvrent à proximité ce qui semble être un paradis vierge, une planète aux immenses montagnes couronnées de nuages et aux magnifiques forêts qui pourrait être tout aussi viable qu’Origae-6. Pourtant, très vite, le paradis va révéler sa réalité infernale. Ce monde regorge de dangers inconnus et mortels. Les survivants vont tout tenter pour échapper à une menace qui dépasse l’entendement… 2 NOTES DE PRODUCTION Dans l’espace, personne ne vous entend crier… Près de quarante ans après, ces mots évoquent toujours avec autant de force l’intensité oppressante d’ALIEN, LE HUITIÈME PASSAGER, le chef-d’œuvre de l’horreur futuriste signé Ridley Scott. -

A Labour History of Irish Film and Television Drama Production 1958-2016

A Labour History of Irish Film and Television Drama Production 1958-2016 Denis Murphy, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted for the award of PhD January 2017 School of Communications Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Dublin City University Supervisor: Dr. Roddy Flynn I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD, is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ___________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: 81407637 Date: _______________ 2 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 12 The research problem ................................................................................................................................. 14 Local history, local Hollywood? ............................................................................................................... 16 Methodology and data sources ................................................................................................................ 18 Outline of chapters ....................................................................................................................................... -

Ira Finkelstein's Day of the Dead

FEATURE FILM IRA FINKELSTEIN’S DAY OF THE DEAD A TIMELESS COMING-OF-AGE COMEDY ADVENTURE CONNECTING GENERATIONS AND CULTURES Story by The Von Piglet Sisters Sue Corcoran & Angie Louise Written by Angie Louise Produced by Deborah Moore & Jane Charles Directed by Sue Corcoran LogLine Ira J. Finkelstein is afraid of growing up. At 13, Ira is expected to “be a man”. All Ira really wants is to get close to Maria, the beautiful Mexican-American girl who is his scene partner in 8th grade drama class. When Maria’s family is unexpectedly deported, Ira hits the road with his Grandpa Sam to find her. Ira learns what it really means to be a man and stand up for what he believe in: family, adventure, and love without borders. Synopsis Ira J. Finkelstein is afraid of growing up. At 13, Ira is expected to “be a man”. All Ira really wants is to get close to Maria, the beautiful Mexican-American girl who is his scene partner in 8th grade drama class. When Maria’s mother is unexpectedly deported, Maria follows her back to Mexico. Panicked, Ira ditches school to search for her but is busted by Grandpa Sam. When Ira begs for his help, Grandpa Sam is unable to resist Ira’s plea as well as his own longing for a youthful adventure. Grandfather and Grandson hit the road in Grandpa’s ’67 Chevy, bound for Mexico and Maria. In Mexico, things go wrong fast. Sam and Ira are robbed by a gang of teen punks, have a run-in with the police and land in jail after a midnight Day of the Dead festival. -

Sxsw Film Festival Announces 2018 Features and Opening Night Film a Quiet Place

SXSW FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES 2018 FEATURES AND OPENING NIGHT FILM A QUIET PLACE Film Festival Celebrates 25th Edition Austin, Texas, January 31, 2018 – The South by Southwest® (SXSW®) Conference and Festivals announced the features lineup and opening night film for the 25th edition of the Film Festival, running March 9-18, 2018 in Austin, Texas. The acclaimed program draws thousands of fans, filmmakers, press, and industry leaders every year to immerse themselves in the most innovative, smart and entertaining new films of the year. During the nine days of SXSW 132 features will be shown, with additional titles yet to be announced. The full lineup will include 44 films from first-time filmmakers, 86 World Premieres, 11 North American Premieres and 5 U.S. Premieres. These films were selected from 2,458 feature-length film submissions, with a total of 8,160 films submitted this year. “2018 marks the 25th edition of the SXSW Film Festival and my tenth year at the helm. As we look back on the body of work of talent discovered, careers launched and wonderful films we’ve enjoyed, we couldn’t be more excited about the future,” said Janet Pierson, Director of Film. “This year’s slate, while peppered with works from many of our alumni, remains focused on new voices, new directors and a range of films that entertain and enlighten.” “We are particularly pleased to present John Krasinski’s A Quiet Place as our Opening Night Film,” Pierson added.“Not only do we love its originality, suspense and amazing cast, we love seeing artists stretch and explore. -

BOD-Update-3.7.13-FINAL.Pdf

______________________________________________________________________________ MEMORANDUM To: Board of Directors From: Amy Lillard Date: March 7, 2013 Re: Bi-Weekly Update March has arrived and I’m heading to SxSW tomorrow. We have dinners planned and meetings arranged, and we’re looking forward to Austin! Incentive Projects New Applications Pat Peach, Line Producer, and three Producers associated with the Hallmark TV pilots scouted Washington locations last week. We expect their application shortly, and when I receive their paperwork, I will update the Board. We are still waiting for the complete application for the feature film Tokarev (Hannibal Pictures). Amy and Julie had a conference call with the Production Attorney and the Director of Development from Hannibal Pictures. We remain optimistic that their finances will be secured, however they do not have their financing complete at this time. Once the funds are secured, we will post the project for the full board’s review. Amy spoke with Nick Morton and Rick Rosenthal from Whitewater Films, about the feature film, Seven Minutes, which they want to begin filming in May. We expect application paperwork shortly. Current Projects Laggies Amy spoke with Anonymous Content about a new start date for Laggies. The delay is due to talent availability, and when I have more details I will update the Board. Lucky Them Lucky Them wrapped principal photography on 2/28. Staff invited Tacoma legislators to visit the set, but they all declined due to the current legislative session. Past Projects Safety Not Guaranteed The 28th Independent Spirit Awards named Safety Not Guaranteed, the year's Best First Screenplay. -

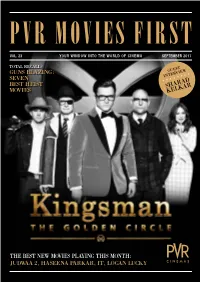

Sharad Kelkarguest INTERVIEW

PVR MOVIES FIRST VOL. 23 YOUR WINDOW INTO THE WORLD OF CINEMA SEPTEMBER 2017 TOTAL RECALL: guest GUNS BLAZING: interview SEVEN BEST HEIST SHARAD MOVIES KELKAR THE BEST NEW MOVIES PLAYING THIS MONTH: JUDwaa 2, HASEENA PARKAR, IT, LOGAN LUCKY GREETINGS ear Movie Lovers, Revisit “The Apartment , “ a classic romantic comedy directed by Billy Wilder . Here’s the September edition of Movies First, your exclusive window to the world of cinema. T ake a peek at the life and films of legendary lyricist and filmmaker Gulzar , and join us in wishing Hollywood This month is packed with high-octane thrillers. superstar Keanu Reeves a Happy Birthday. Watch the Kingsman spies match wits and strength We really hope you enjoy the issue. Wish you a fabulous with a secret enemy. Arjun Rampal portrays the dark month of movie watching. life of mafia don Arun Gawli in “Daddy,” while Shraddha Kapoor traces the journey of crime queen “Haseena Regards Parkar .” Ajay Devgn pulls off a daring 70s-style heist Gautam Dutta in “Baadshaho.” CEO, PVR Limited USING THE MAGAZINE We hope youa’ll find this magazine easy to use, but here’s a handy guide to the icons used throughout anyway. You can tap the page once at any time to access full contents at the top of the page. PLAY TRAILER SET REMINDER BOOK TICKETS SHARE PVR MOVIES FIRST PAGE 2 CONTENTS London’s top spies The Kingsman are back with a new adventure. Turn the pages to get a peek inside their new mission. Tap for... Tap for... Movie OF THE MONTH GUEST INTERVIEW Tap for.. -

ALIENCOVENANT PB Ita 2

! Regia di Ridley Scott Michael Fassbender Katherine Waterston Billy Crudup Danny McBride Demian Bichir *** Uscita: 11 Maggio 2017 Distribuzione: 20th Century Fox Italia Durata: 121 minuti *** Ufficio stampa 20th Century Fox Giancarlo Sozi : <[email protected]> Cristina Partenza: < [email protected]> Ufficio stampa web Alessandra Giovannetti <[email protected]> *** #AlienCovenant https://www.facebook.com/AlienFilmIt/ http://www.aliencovenant-trovasala.it/ www.20thfox.it Nello spazio nessuno può sentirti urlare. Dopo quasi quattro decadi, queste parole rimangono sinonimo dell'assoluta e incessante tensione di quel capolavoro dell’orrore fantascientifico che è stato Alien di Ridley Scott. Ora, il padre del leggendario franchise, ritorna ancora una volta al mondo che ha creato per esplorarne i suoi recessi più oscuri con ALIEN: COVENANT, una nuova avventura al cardiopalma che spinge in avanti i confini del terrore per i film vietati ai minori. A bordo dell’astronave Covenant tutto è tranquillo; l’equipaggio e le altre 2.000 anime sul vascello d’esplorazione sono profondamente addormentate nell’iper-sonno, lasciando che Walter, l’organismo sintetico a bordo, cammini da solo per i corridoi. La nave è in viaggio verso il lontano pianeta Origae-6, sul fianco estremo della galassia, dove i coloni sperano di stabilire un nuovo avamposto per l’umanità. La pacifica tranquillità del viaggio viene interrotta quando una vicina esplosione stellare distrugge le vele di raccolta di energia della Covenant, provocando decine di vittime e facendo deragliare la missione. Ben presto i membri superstiti dell’equipaggio scoprono quello che sembra essere un paradiso inesplorato, un Eden indisturbato con montagne coperte di nuvole e immensi alberi altissimi, molto più vicino di Origae-6 e potenzialmente altrettanto valido per ospitarli. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

The Future of India's Entertainment Industry

EMBRACING NONLINEARITY: THE FUTURE OF INDIA’S ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY November 2020 | No. 005 1 AUTHORS SHEKHAR KAPUR VANI TRIPATHI TIKOO IS AN AWARD-WINNING FILMMAKER AND IS A CREATIVE PROFESSIONAL, AN ACTOR, CHAIRMAN OF THE FILM AND TELEVISION PRODUCER AND MEMBER, CENTRAL BOARD INSTITUTE OF INDIA OF FILM CERTIFICATION. AKSHAT AGARWAL VIVAN SHARAN IS A LAWYER . IS ADVISOR, ESYA CENTRE. DESIGN : ILLUSTRATIONS BY TANIYA O’CONNOR, DESIGN BY DRISHTI KHOKHAR THE ESYA CENTRE IS A NEW DELHI BASED THINK TANK. THE CENTRE’S MISSION IS TO GENERATE EMPIRICAL RESEARCH AND INFORM THOUGHT LEADERSHIP TO CATALYSE NEW POLICY CONSTRUCTS FOR THE FUTURE. IT AIMS TO BUILD INSTITUTIONAL CAPACITIES FOR GENERATING IDEAS THAT WILL CONNECT THE TRIAD OF PEOPLE, INNOVATION AND VALUE, TO HELP REIMAGINE THE PUBLIC POLICY DISCOURSE IN INDIA. MORE DETAILS CAN BE FOUND AT WWW.ESYACENTRE.ORG 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY / 5 THE NEW MEDIA / 7 OTT – A MEANS AND NOT AN END / 8 I. THE OTT EFFECT / 9 II. UNLEASHING CREATIVE EXPRESSION / 9 III. EXPANSION OF CHOICE / 10 IV. HYPER-PERSONALIZED ENTERTAINMENT / 12 V. OPPORTUNITIES FOR FUTURE GROWTH / 12 THE FUTURE OF STORYTELLING / 15 I. ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE / 15 II. GAMING / 17 III. VIRTUAL AND AUGMENTED REALITY / 18 LEVERAGING OUR STRENGTHS / 21 I. OUR CULTURE / 21 II. OUR PEOPLE / 22 III. OUR CREATIVE INDUSTRIES / 23 ENABLING ESSENTIAL TRANSFORMATIONS / 27 I. CREATIVE FREEDOM / 27 II. UNLEASHING VALUE THROUGH HARDWARE LOCALISATION / 27 III. PRINCIPLE BASED REGULATION: LEVELLING THE PLAYING FIELD BETWEEN CREATIVE INDUSTRIES / 28 NOTES / 29 3 4 SUMMARY India’s media and entertainment industries have always We examine the factors that can make India a dominant been an important part of our national story. -

Transmedia Storytelling Strategy

Transmedia Storytelling Strategy How and why producers use transmedia storytelling for competitive advantage. Cameron Cliff Bachelor of Film and Screen Media, Bachelor of Creative Industries (Honours) Principal Supervisor: Dr Jon Silver Associate Supervisor: Distinguished Professor Stuart Cunningham Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of a Doctor of Philosophy School of Media, Entertainment and Creative Arts Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology 2017 1 Keywords Transmedia, storytelling, strategy, competitive advantage, multiplatform, Hollywood, Lizzie Bennet Diaries, Pride and Prejudice, Sofia’s Diary, Doctor Who, BBC ii Abstract Storytelling in contemporary media production exists in a landscape of rapid and continuous change. Practitioners and scholars alike have been exploring different methods for success within this landscape, fixating on multiplatform strategies that blend together novel and traditional methods of telling their stories. As a result, transmedia storytelling, the strategy of creating an immersive world through the coordination of multiple, unique narratives, has enjoyed a place of prominence within media production research for the better part of the last decade. However, the concept of transmedia storytelling has become clouded by ‘semantic chaos’ (Scolari 2009). Investigations from different disciplines and industries have formed separate silos of research that have divided transmedia and left professionals questioning the relevance of transmedia storytelling to their practice. Using strategic management theory to coordinate research from across different disciplinary silos (media and cultural studies, marketing and advertising), this thesis conducts an original, interdisciplinary study of transmedia storytelling. It develops an audience engagement framework specific to transmedia projects and a lens for assessing the competitive advantage of different transmedia strategies.