2014 Invisible Ink Chemistry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing About Espionage Secrets

Secrecy and Society ISSN: 2377-6188 Volume 2 Number 1 Secrecy and Intelligence Article 7 September 2018 Writing About Espionage Secrets Kristie Macrakis Georgia Tech, Atlanta, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/secrecyandsociety Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Macrakis, Kristie. 2018. "Writing About Espionage Secrets." Secrecy and Society 2(1). https://doi.org/10.31979/2377-6188.2018.020107 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/ secrecyandsociety/vol2/iss1/7 This Special Issue Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Information at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Secrecy and Society by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Writing About Espionage Secrets Abstract This article describes the author’s experiences researching three books on espionage history in three different countries and on three different topics. The article describes the foreign intelligence arm of the Ministry for State Security; a global history of secret writing from ancient to modern times; and finally, my current project on U.S. intelligence and technology from the Cold War to the War on Terror. The article also discusses the tensions between national security and openness and reflects on the results of this research and its implications for history and for national security. Keywords Central Intelligence Agency, CIA, -

STEM @ HOME GUIDE: Invisible Ink

STEM @ HOME GUIDE: Invisible Ink • Aim: To write a secret message using lemons • Materials required: Lemon HELPFUL TIPS Water You can use fresh lemons or Small Bowl lemon juice. Q Tips or paint brush White paper Don’t get the paper too wet or it will take much longer to dry. Heat source (bright lightbulb, candle, stovetop) BE CAREFUL AND HAVE AN ADULT HANDLE THE HEAT SOURCE Using a candle or stove will work much faster, but a lightbulb will work as well. • Questions to think about before you start: How can I use a lemon to write a secret message? Why do we need heat? • Instructions: Make sure to perform the experiment as a team (parent and student). Parent: Cut the lemon in half . Student: Squeeze half of the lemon into a bowl or cup and add a small amount of water . Student: Stir the lemon juice and water together . Student: Optional: You can write a decoy message in pen or pencil before you write your secret message. Student: Take your Q tip or brush and dip it into the lemon water and write your secret message on the paper. Parent: Once the paper is dry hold the paper over your chosen heat source to reveal the secret message. Be careful not to hold it to close or it may catch on fire • Extensions Activities: Does it matter which side of the paper you expose to the heat? Try using another acidic substance like orange juice, milk, honey or vinegar to write your messages, notice which substances work better. -

Brazilian Journal of Forensic Sciences, Medical Law and Bioethics 7(3):156-161 (2018)

Brazilian Journal of Forensic Sciences, Medical Law and Bioethics 7(3):156-161 (2018) Brazilian Journal of Forensic Sciences, Medical Law and Bioethics Journal homepage: www.ipebj.com.br/forensicjournal Decipherment of Disappeared Ink: A Case Study Deshpande Hemantini*, Mulani Khudbudin Regional Forensic Science Laboratory, Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India-431002 * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The disappeared or invisible inks are fluids used to for secret writing. These types of inks are revealed by heat, chemical reaction and UV light. Disappearing inks are acid base indicators showing different colours at different pH. Writing with this type of ink disappears after about 65 h. These inks could be used for forging the documents such as agreements, cheques, property documents and other important documents. Many destructive and non- destructive methods are available for forensic decipherment of these disappeared writing. In present communication, a simple nondestructive method is applied for decipherment of disappeared signatures on share transfer agreement and other related documents. Keywords: Forensic Science, Disappearing ink. 1. Introduction Basically, ink is a composition of dyes or pigments along with some additives to give desired physical properties. Nowadays, varieties of ink composition are available in the market which consists of various organic, inorganic and synthetic material with various characteristics and properties1,2. Disappearing ink is used as marking system for sports, in dress making industry. It is also used as teaching material to make answer invisible. By using coloring agents, answers become visible. Disappearing inks are also applied in paint industries to locate the area which is not painted. However, these are a great challenge for forensic document examiner as used in forgery or counterfeiting documents. -

Invisible Ink

Excitement in Chemistry Sourav Pal National Chemical Laboratory, Pune- 411008 [email protected] NCL Outreach, 17 January, 2010 http://www.ncl.org.in/tcs/estg/spalhomepage.html NATIONAL CHEMICAL LABORATORY, PUNE, INDIA “Science is organized and systematized knowledge relating to our physical world Observation of phenomena as they occur in nature and their faithful recording As the observations multiplied, regularities were sought and the facts were systematized. Formulation into laws, capable of embracing a number of facts and of summarizing them in succinct form with predictive power, these laws became theory. By comparison with experiments theories can be refined and new principles discovered” . Scientific method or temper Correlation of facts or explanation of qualitative information. Quantification and understanding in terms of laws and objectivity Combination of experiment and theory using the scientific method has led to the development of present science. Chemistry: Study of substances, their properties, structures and transformations. Synthesis of molecules of great complexity Chemistry • Chemistry is the study of matter and interactions between them. • Chemistry and Physics are closely related. ( chemical Physics) • Chemistry tends to focus on the properties of substances and the interactions between different types of matter, involving study of electrons. Physics tends to focus more on the nuclear part of the atom, as well as the subatomic realm. CHEMISTRY MOVES ON TWO WHEELS CURIOSITY UTILITY George Whitesides What Fields of Study Use Chemistry • Chemistry is used in most fields, but it's commonly seen in the sciences and in medicine. Chemists, physicists, biologists, and engineers study chemistry. • Chemistry is the central science. -

Invisible Ink

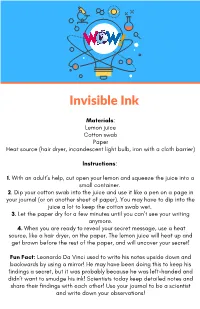

Invisible Ink Materials: Lemon juice Cotton swab Paper Heat source (hair dryer, incandescent light bulb, iron with a cloth barrier) Instructions: 1. With an adult’s help, cut open your lemon and squeeze the juice into a small container. 2. Dip your cotton swab into the juice and use it like a pen on a page in your journal (or on another sheet of paper). You may have to dip into the juice a lot to keep the cotton swab wet. 3. Let the paper dry for a few minutes until you can’t see your writing anymore. 4. When you are ready to reveal your secret message, use a heat source, like a hair dryer, on the paper. The lemon juice will heat up and get brown before the rest of the paper, and will uncover your secret! Fun Fact: Leonardo Da Vinci used to write his notes upside down and backwards by using a mirror! He may have been doing this to keep his findings a secret, but it was probably because he was left-handed and didn’t want to smudge his ink! Scientists today keep detailed notes and share their findings with each other! Use your journal to be a scientist and write down your observations! Tinta Invisible Materiales: Zumo de limón Bastoncillo de algodón Papel Fuente de calor (secador de pelo, bombilla incandescente, plancha con barrera de tela) Instrucciones: 1. Con la ayuda de un grande, abre tu limón y exprime el zumo en un recipiente pequeño. 2. Sumerge el bastoncillo en el zumo y úsalo como si fuera una pluma en una página en su diario (o en otra hoja de papel). -

How to Make Invisible Ink

How To Make Invisible Ink Using common ingredients found in your home, you can easily create secret messages that are unseen by the naked eye. But when a little science is applied, the message mysteriously appears. This is perfect for passing notes among friends and siblings that are for their eyes only. Make sure you and your partner are familiar with the methods used to create and read the messages. Note that you don’t need all of the items listed Items Needed • Baking powder and water / Grape juice • Vinegar or lemon juice / Hair dryer or lamp or other heat source • Clear liquid laundry detergent / Black light • Whole milk / Pencil and sandpaper • Cotton swab or toothpick Instructions for acids & bases invisible ink 1. Mix two tablespoons of baking soda and two tablespoons of water. Using a cotton swab or toothpick, dip it in the mixture and write your message on a piece of paper. Let it dry. 2. Dip a sponge or new cotton swab in grape juice and “paint” over the paper with the secret message to reveal it. 3. This works because a base reacts with an acid and produces a different color. Acids are sour materials (like the grape juice) that has a chemical reaction when mixed with bases (baking soda). In this case, the chemical reaction is that a new color is produced. Instructions for heat activated invisible ink 1. Pour some vinegar or lemon juice in a cup and dip a cotton swab or toothpick in the cup. Write out your secret message on paper and let it dry. -

An Evaluation of Some Commonly Used Methods for Visualization of Secret Writing

Research Journal of Forensic Sciences _______________________________________________ ISSN 2321–1792 Vol. 1(3), 1-4, May (2013) Res. J. Forensic Sci. An Evaluation of Some commonly used Methods for Visualization of Secret Writing Deepti Andharmule, Neeti Kapoor, Ashish Badiye* Institute of Forensic Science (Govt. of Maharashtra), RTM Nagpur University, Nagpur, MH, INDIA Available online at: www.isca.in Received 8th March 2013, revised 17th April 2013, accepted 25th April 2013 Abstract Secret writing is the art of covered or hidden writing. The art of secret writing is intended to make a message unreadable by at Third party but does not hide the existence of the secret communication. This paper is intended as a technical introduction to secret writing for those unfamiliar with the field. The current research paper comprises of twenty seven samples which contained hidden messages written using some biological fluids (milk, saliva, and urine), chemical fluids (vinegar, saline and baking soda) and vegetable fluids (lemon, orange and onion juice). They were then visualized using physical method (UV lamp), by heat treatment, and by chemical method in a specific interval of time, examine from 1st day to 30th day after regular interval of five days. Keywords: Secret writing, hidden messages, invisible ink. Introduction Invisible Inks: Basics: Broadly, invisible inks can be categorized as: organic fluids and sympathetic inks. The former Invisible inks are used for secret writing. These are fluids used consists of the “natural” methods many of us tried our hand at as to write hidden messages that do not appear unless exposed by a kids: lemon juice, vinegar, milk, sweats saliva, onion juice, and revealing process. -

Invisible Inks with Household Ingredients: Mechanisms and Properties

Invisible Inks With Household Ingredients: Mechanisms and Properties Ben Artin Northeastern University College of Professional Studies CMH1011: Chemical Principles 1 Instructor: Patricia Brandl June 24, 2011 Abstract Invisible inks | colorless substances usable for writing that can be turned to color using a chemical process | have both practical value in covert communications and educational value in chemistry teaching. Publicly available invisible ink recipes are numerous and varied, but are often published without any elaboration as to their utility and usability. This paper evaluates approximately a dozen different invisible ink recipes, with focus on those that can be prepared from common household ingredients. Safety, cost, availability, shelf-life, and dif- ficulty of use of the different invisible inks are considered. Based on this evaluation, a general recommendation is made in favor of heat-based inks for casual covert communications and chemistry education, and precipitation-based inks for more secure covert communications and chemistry education in a lab setting. Additionally, two proposed mechanisms for action of invisible inks based on organic acids and revealed by heating are evaluated. Oxidation of ink by heat is confirmed to play a role in revealing such inks. 1 Introduction ing mathematics2, computer science3, quan- tum physics4, and chemistry5. Parents want to know about the activities of In the realm of chemistry, a popular tech- their children; generals want to know about the nique for covert communication | seen in sci- activities of their troops. Throughout human ence education6, intelligence operations5, and history, on scale from personal to international, mass-market fiction7 | are invisible inks. knowledge has been a key ingredient in power. -

Invisible Gas, Invisible Ink

Teacher Instructions Invisible Gas, Invisible Ink Overview: Scientists use ultraviolet light to detect the amount of sulfur dioxide in volcanic gases. In this activity, students model ultraviolet detection strategies by investigating “invisible inks” that glow under an ultraviolet-emitting light. Objectives: The student will: • observe how ultraviolet light can be used to detect colorless substances; • conduct an investigation to see which substance creates the best invisible ink under ultraviolet light; and • explain how the absorption of ultraviolet light leads to the fluorescence of substances. Materials: • Hand-held black light • Tonic water (must contain quinine) • Bubbly, clear soft drink to compare to tonic water • Cotton swabs • Toothpicks • Vinegar • Liquid laundry detergent with whiteners • Vitamin B-12 tablets • White paper • Clear plastic cups • Permanent marker • Student Worksheet: “Invisible Ink” Answers to Student Worksheet: Data: Answers will vary Analysis of Data: 1. Answers will vary 2. Answers will vary Conclusion: 1. Answers will vary 2. Answer will vary, but process of testing and evidence of ink quality should be described. Further Questions: 1. The substances glow because ultraviolet is absorbed, causing visible light (fluorescence) to be emitted. Ola Ka Honua: Volcanoes Alive 186 ©2001, 2007 UAF Geophysical Institute Teacher Instructions Invisible Gas, Invisible Ink Activity Procedure: 1. Show students two liquids, each in a clear plastic cup: tonic water and a clear soft drink. Ask students if they can tell the difference between the two substances using vision alone. 2. Shine a black light on the two substances. Tell students that the black light emits ultraviolet light. The surface of the tonic water should glow blue, while the other liquid will not. -

Invisible Ink Ages 4-10 Prepared by University of Rochester Igem

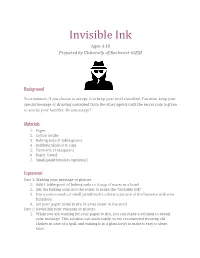

Invisible Ink Ages 4-10 Prepared by University of Rochester iGEM Background Your mission, if you choose to accept, is to keep your intel classified. You must keep your special message or drawing concealed from the other agents until the secret code is given to you by your handler. Do you accept? Materials 1. Paper 2. Cotton swabs 3. Baking soda (1 tablespoon) 4. Rubbing alcohol (1 cup) 5. Turmeric (1 teaspoon) 6. Paper Towel 7. Small paint brushes (optional) Experiment Part 1: Making your message or picture 1. Add 1 tablespoon of baking soda to ½ cup of water in a bowl 2. Stir the baking soda into the water to make the “invisible ink” 3. Use a cotton swab or small paintbrush to draw a picture of the bacteria with new functions 4. Set your paper aside to dry (it dries faster in the sun!) Part 2: Revealing your message or picture 5. While you are waiting for your paper to dry, you can make a solution to reveal your message! This solution can stain easily, so we recommend wearing old clothes in case of a spill, and mixing it in a glass bowl to make it easy to clean later. 6. Add 1 teaspoon of turmeric to ½ cup of rubbing alcohol 7. Stir the turmeric into the water 8. After you paper has dried, use a paper towel or paintbrush to apply the color changing solution 9. Your secret message or picture is now revealed! How does this experiment work? Today, we made a chemically activated invisible ink. -

Invisible Ink Experiment

Invisible Ink Experiment Safety and First Aid This section will only deal with the specific safety issues regarding the chemicals involved and used in the video. There are likely to be other safety issues that will need to be addressed outside the scope of this section. A full risk assessment should be performed prior to undertaking the experiment. Students should not ingest any of the experiment; good lab practice starts young! This experiment requires the use of a heat source. Care should be taken to prevent burns. First Aid – wash the affected area with water. Standard burn first aid should be followed. Suggested Teaching Points Acids – this experiment relies on the acidic nature of lemon juice Chemical reactions are temperature dependent – this reaction highlights the dependency of the rate of a chemical reaction on temperature What to Expect Please see the video for a detailed depiction of the experiment. It should be noted that this is not the only method for invisible ink experiments (see Suggested Improvements section). This experiment will allow students to draw a picture or write a message that will be invisible until a source of heat is applied to the paper. In this experiment, we are using the naturally acid nature of lemon juice to act as our ink. When placed on the paper, the water from the lemon juice evaporates to leave behind the citric acid present in the juice. The citric acid reacts with the fibres of the paper, damaging them. As a result of this damage, when an external heat source is applied, these areas of the paper burn much more rapidly than the untreated paper, revealing the initial message as brown areas on the paper. -

Invisible Ink Formulas

INVISIBLE INK FORMULAS FORMULA #1 FORMULA #5 » 1 Tablet of Laxative » Vinegar or Lemon Juice » 1 Tablespoon Rubbing Alcohol » Red Cabbage Water (chop one large red cabbage into small pieces Cotton balls » Note: blackberries, red onions, or even hibiscus » Household Ammonia flowers can be used as well – simmer the cabbage pieces until the water turns a deep shade of purple. Mash the laxative tablet into the tablespoon of alcohol. Be sure Allow the water to cool. Refrigerate when not in use). the tablet is entirely dissolved. Write a message on the paper Write your message in lemon juice or vinegar and wait for it to with paintbrush dipped into the solution. As the solution dries, dry (or use hair dryer). Using a spray bottle, mist red cabbage the writing will disappear. To develop the message: dampen water over it to expose the message. the cotton ball with liquid ammonia and dab it on the page. The writing will reappear. FORMULA #6 FORMULA #2 » 3 Tablespoons Baking Soda » Lemon Juice » 3 Tablespoons Water » Heat Source » Grape Juice Write your message in lemon juice and wait for it to dry. Use a Mix about 3 tablespoons of baking soda and 3 tablespoons hair dryer, iron or light bulb (carefully) to expose the message. water. Write with this mixture on paper and let it dry. Paint or rub the grape juice across the paper to expose the message. FORMULA #3 FORMULA #7 » Vinegar » 1 Teaspoon Corn Starch » Heat Source » 1/4th Cup Water Write your message in vinegar and wait for it to dry (or use hair dryer).