Ataxioceras (Ataxioceras) Lopeztichae Cantú-Chapa, 1991: Updating the Systematic and Palaeobiogeographic Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gallois, R. W. 2005. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association, Vol

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by NERC Open Research Archive Gallois, R. W. 2005. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, Vol. 116, 33-43. ON THE KIMMERIDGIAN SUCCESSIONS OF THE NORMANDY COAST , NORTHERN FRANCE . R. W. Gallois Gallois, R. W. 2005. On the Kimmeridgian successions of the Normandy coast, northern France. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association , Vol. 116, 33-43. ABSTRACT Kimmeridgian rocks crop out on the Normandy coast north and south of the Seine Estuary at Le Havre in a series of small foreshore and cliff exposures separated by beach deposits and landslips. A total thickness of about 45m of richly fossiliferous strata is exposed, ranging from the base of the Baylei Zone to the middle part of the Eudoxus Zone. The sections are mostly unprotected by sea-defence works and are subject to rapid marine erosion and renewal. Taken together, the Normandy exposures currently provide a more complete section through the low and middle parts of the Kimmeridgian Stage than any natural English section, including those of the Dorset type area. Descriptions and a stratigraphical interpretation of the Normandy sections are presented that enable the faunal collections to be placed in their regional chronostratigraphical context. The Kimmeridgian succession at outcrop on the Normandy coast contains numerous sedimentary breaks marked by erosion, hardground and omission surfaces. Some of these are disconformities that give rise to rapid lateral variations in the succession: biostratigraphical studies need therefore to be carried out with particular care. 1. INTRODUCTION The Kimmeridgian rocks of the Dorset type area and the Normandy coast are richly fossiliferous marine mudstones and limestones. -

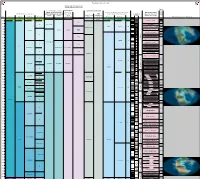

Expanded Jurassic Timescale

TimeScale Creator 2012 chart Russian and Ural regional units Russia Platform regional units Calca Jur-Cret boundary regional Russia Platform East Asian regional units reous stages - British and Boreal Stages (Jur- Australia and New Zealand regional units Marine Macrofossils Nann Standard Chronostratigraphy British regional Boreal regional Cret, Perm- Japan New Zealand Chronostratigraphy Geomagnetic (Mesozoic-Paleozoic) ofossil stages stages Carb & South China (Neogene & Polarity Tethyan Ammonoids s Ma Period Epoch Age/Stage Substage Cambrian) stages Cret) NZ Series NZ Stages Global Reconstructions (R. Blakey) Ryazanian Ryazanian Ryazanian [ no stages M17 CC2 Cretaceous Early Berriasian E Kochian Taitai Um designated ] M18 CC1 145 Berriasella jacobi M19 NJT1 Late M20 7b 146 Lt Portlandian M21 Durangites NJT1 M22 7a 147 Oteke Puaroan Op M22A Micracanthoceras microcanthum NJT1 Penglaizhenian M23 6b 148 Micracanthoceras ponti / Volgian Volgian Middle M24 Burckhardticeras peroni NJT1 Tithonian M24A 6a 149 M24B Semiformiceras fallauxi NJT15 M25 b E 150 M25A Semiformiceras semiforme NJT1 5a Early M26 Semiformiceras darwini 151 lt-Oxf N M-Sequence Hybonoticeras hybonotum 152 Ohauan Ko lt-Oxf R Kimmeridgian Hybonoticeras beckeri 153 m- Lt Late Oxf N Aulacostephanus eudoxus 154 m- NJT14 Late Aspidoceras acanthicum Oxf R Kimmeridgian Kimmeridgian Kimmeridgian Crussoliceras divisum 155 155.431 Card- N Ataxioceras hypselocyclum 156 E Early e-Oxf Sutneria platynota R Idoceras planula Suiningian 157 Cal- Oxf N Epipeltoceras bimammatum 158 lt- Lt Callo -

Palaeoecology and Palaeoenvironments of the Middle Jurassic to Lowermost Cretaceous Agardhfjellet Formation (Bathonian–Ryazanian), Spitsbergen, Svalbard

NORWEGIAN JOURNAL OF GEOLOGY Vol 99 Nr. 1 https://dx.doi.org/10.17850/njg99-1-02 Palaeoecology and palaeoenvironments of the Middle Jurassic to lowermost Cretaceous Agardhfjellet Formation (Bathonian–Ryazanian), Spitsbergen, Svalbard Maayke J. Koevoets1, Øyvind Hammer1 & Crispin T.S. Little2 1Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1172 Blindern, 0318 Oslo, Norway. 2School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, United Kingdom. E-mail corresponding author (Maayke J. Koevoets): [email protected] We describe the invertebrate assemblages in the Middle Jurassic to lowermost Cretaceous of the Agardhfjellet Formation present in the DH2 rock-core material of Central Spitsbergen (Svalbard). Previous studies of the Agardhfjellet Formation do not accurately reflect the distribution of invertebrates throughout the unit as they were limited to sampling discontinuous intervals at outcrop. The rock-core material shows the benthic bivalve fauna to reflect dysoxic, but not anoxic environments for the Oxfordian–Lower Kimmeridgian interval with sporadic monospecific assemblages of epifaunal bivalves, and more favourable conditions in the Volgian, with major increases in abundance and diversity of Hartwellia sp. assemblages. Overall, the new information from cores shows that abundance, diversity and stratigraphic continuity of the fossil record in the Upper Jurassic of Spitsbergen are considerably higher than indicated in outcrop studies. The inferred life positions and feeding habits of the benthic fauna refine our understanding of the depositional environments of the Agardhfjellet Formation. The pattern of occurrence of the bivalve genera is correlated with published studies of Arctic localities in East Greenland and northern Siberia and shows similarities in palaeoecology with the former but not the latter. -

Oxfordian Idoceratids (Ammonoidea) and Their Relation to Perisphinctes Proper

ACT A PAL A EON T 0 L ,0 GI CAP 0 LON ICA Vol. 21 1976 No 4 WOJCIECH BROCHWICZ-LEWINSKI & ZDZISLAW ROZAK OXFORDIAN IDOCERATIDS (AMMONOIDEA) AND THEIR RELATION TO PERISPHINCTES PROPER Abstract. - An attempt is made to reconstruct the evolution of idoceratids (Pe risphinctidae) during the Oxfordian. The subgenus Nebrodites (Passendorjeria) is supposed to be the ancestor of N. (Mesosimoceras), whilst N. (Enayites) subgen. n. of N. (Nebrodites) and possibly of Idoceras planula group. Both genera appear to be of European origin. Differentiation of Mediterranean and Submediterran.ean peris phinctidae appears questionable. INTRODUCTION In 1973 one of the co-authors (W. Brochwicz-Lewiilski, 1973) proposed a new subgenus Nebrodites (Passendorferia) for Middle Oxfordian forms interpreted as descendants of Mediterranean Kranaosphinctes cyrilli-me thodii group and ancestors of Nebrodites proper; the Idoceras planula group was assumed to be an off-shoot of the evolutionary line. Subsequent collecting gave several Passendorferia and Passendorferia-like forms from the Oxfordian of Poland, Switzerland (Gygi, pers. inf.), Spain (Sequeiros, 1974) and Bulgaria (Sapunov, in press). Moreover, ancestral forms of the Idoceras planula group were reported from the Bimammatum Zone of the F. R. G. (Nitzopoulos, 1974). These finds made it possible to draw some conclusions concerning the h~tory of these Mediterranean perisphinctids and their relationship to the Submediterranean ones. The material described comprises forms from authors' G. KU'lesza (Br, Kl) and Dr. J. Liszkowski's (L) collections housed at the Warsaw University as well as others from the Geological Museum of Sofia Univer sity (Bulgaria) and Geological Museum of the Polish Academy of Sciences at Cracow. -

Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) Cold-Water Idoceratids (Ammonoidea) from Southern Coahuila, Northeastern Mexico, Associated with Boreal Bivalves and Belemnites

REVISTA MEXICANA DE CIENCIAS GEOLÓGICAS Kimmeridgian cold-water idoceratids associated with Boreal bivalvesv. 32, núm. and 1, 2015, belemnites p. 11-20 Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) cold-water idoceratids (Ammonoidea) from southern Coahuila, northeastern Mexico, associated with Boreal bivalves and belemnites Patrick Zell* and Wolfgang Stinnesbeck Institute for Earth Sciences, Heidelberg University, Im Neuenheimer Feld 234, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany. *[email protected] ABSTRACT et al., 2001; Chumakov et al., 2014) was followed by a cool period during the late Oxfordian-early Kimmeridgian (e.g., Jenkyns et al., Here we present two early Kimmeridgian faunal assemblages 2002; Weissert and Erba, 2004) and a long-term gradual warming composed of the ammonite Idoceras (Idoceras pinonense n. sp. and trend towards the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary (e.g., Abbink et al., I. inflatum Burckhardt, 1906), Boreal belemnites Cylindroteuthis 2001; Lécuyer et al., 2003; Gröcke et al., 2003; Zakharov et al., 2014). cuspidata Sachs and Nalnjaeva, 1964 and Cylindroteuthis ex. gr. Palynological data suggest that the latest Jurassic was also marked by jacutica Sachs and Nalnjaeva, 1964, as well as the Boreal bivalve Buchia significant fluctuations in paleotemperature and climate (e.g., Abbink concentrica (J. de C. Sowerby, 1827). The assemblages were discovered et al., 2001). in inner- to outer shelf sediments of the lower La Casita Formation Upper Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous marine associations contain- at Puerto Piñones, southern Coahuila, and suggest that some taxa of ing both Tethyan and Boreal elements [e.g. ammonites, belemnites Idoceras inhabited cold-water environments. (Cylindroteuthis) and bivalves (Buchia)], were described from numer- ous localities of the Western Cordillera belt from Alaska to California Key words: La Casita Formation, Kimmeridgian, idoceratid ammonites, (e.g., Jeletzky, 1965), while Boreal (Buchia) and even southern high Boreal bivalves, Boreal belemnites. -

Late Jurassic Ammonites from Alaska

Late Jurassic Ammonites From Alaska GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1190 Late Jurassic Ammonites From Alaska By RALPH W. IMLAY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1190 Studies of the Late jurassic ammonites of Alaska enables fairly close age determinations and correlations to be made with Upper Jurassic ammonite and stratigraphic sequences elsewhere in the world UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1981 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G. WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 81-600164 For sale by the Distribution Branch, U.S. Geological Survey, 604 South Pickett Street, Alexandria, VA 22304 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ----------------------------------------- 1 Ages and correlations ----------------------------- 19 19 Introduction -------------------------------------- 2 Early to early middle Oxfordian -------------- Biologic analysis _________________________________ _ 14 Late middle Oxfordian to early late Kimmeridgian 20 Latest Kimmeridgian and early Tithonian _____ _ 21 Biostratigraphic summary ------------------------- 14 Late Tithonian ______________________________ _ 21 ~ortheastern Alaska ------------------------- 14 Ammonite faunal setting -------------------------- 22 Wrangell Mountains -------------------------- 15 Geographic distribution ---------------------------- 23 Talkeetna Mountains ------------------------- 17 Systematic descriptions ___________________________ _ 28 Tuxedni Bay-Iniskin Bay area ----------------- 17 References -

Curator 10-9 Contents.Qxd

THE GEOLOGICAL CURATOR VOLUME 10, NO. 9 CONTENTS EDITORIAL by Matthew Parkes ............................................................................................................................ 516 PLANT OR ANIMAL, TERRESTRIAL OR MARINE? THOUGHTS ON SPECIMEN CURATION IN UNIVERSITY PALAEONTOLOGICAL TEACHING COLLECTIONS BASED ON AN EXAMPLE FROM OHIO, USA by James R. Thomka ............................................................................................................................ 517 DOMESTIC SCIENCE:THE RECOVERY OF AN ICHTHYOSAUR SKULL Volume 10 Number 9 by Heather Middleton ................................................................................................................ 523 ALEXANDER MURRAY COCKBURN, CURATOR OF THE MUSEUM OF GEOLOGY AT EDINBURGH UNIVERSITY by Peder Aspen ........................................................................................................................... 531 PRESENTATION OF THE A.G. BRIGHTON MEDAL TO GRAHAM WORTON .............................. 535 GEOLOGICAL CURATORS’ GROUP : 43rd ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING .................................. 539 BOOK REVIEWS ............................................................................................................................................. 545 GEOLOGICAL CURATORS’ GROUP - October 2018 GEOLOGICAL CURATORS’ GROUP Registered Charity No. 296050 The Group is affiliated to the Geological Society of London. It was founded in 1974 to improve the status of geology in museums and similar institutions, and to improve -

1501 Rogov.Vp

Aulacostephanid ammonites from the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) of British Columbia (western Canada) and their significance for correlation and palaeobiogeography MIKHAIL A. ROGOV & TERRY P. POULTON We present the first description of aulacostephanid (Perisphinctoidea) ammonites from the Kimmeridgian of Canada, and the first illustration of these ammonites in the Americas. These ammonites include Rasenia ex gr. cymodoce, Zenostephanus (Xenostephanoides) thurrelli, and Zonovia sp. A from British Columbia (western Canada). They belong to genera that are widely distributed in the subboreal Eurasian Arctic and Northwest Europe, and they also occur even in those Boreal regions dominated by cardioceratids. They are important markers for a narrow stratigraphic interval in the Cymodoce Zone (top of Lower Kimmeridgian) and the lower part of the Mutabilis Zone (base of Upper Kimmeridgian) of the Northwest European standard succession. In Spitsbergen and Franz Josef Land, the only Upper Kimmeridgian aulacostephanid-bearing level is the Zenostephanus (Zenostephanus) sachsi biohorizon, which very likely belongs to the Mutabilis Zone. Expansion of Zenostephanus from Eurasia, where it is present over a large area, into British Columbia, is approximately correlative with a transgressive event that also led to expansion of the Submediterranean ammonite ge- nus Crussoliceras through the Submediterranean and Subboreal areas slightly before Zenostephanus. • Key words: Kimmeridgian, aulacostephanids, Zenostephanus, Rasenia, British Columbia, palaeobiogeography, sea-level changes. ROGOV, M.A. & POULTON, T.P. 2015. Aulacostephanid ammonites from the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic) of British Columbia (western Canada) and their significance for correlation and palaeobiogeography. Bulletin of Geosciences 90(1), 7–20 (5 figures). Czech Geological Survey, Prague. ISSN 1214-1119. Manuscript received January 31, 2014; ac- cepted in revised form October 2, 2014; published online November 25, 2014; issued January 26, 2015. -

Characteristic Jurassic Mollusks from Northern Alaska

Characteristic Jurassic Mollusks From Northern Alaska GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 274-D Characteristic Jurassic Mollusks From Northern Alaska By RALPH W. IMLAY A SHORTER CONTRIBUTION TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 274-D A study showing that the northern Alaskan faunal succession agrees with that elsewhere in the Boreal region and in other parts of North America and in northwest Europe UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - BMMH§ts (paper cover) Price $1.00 CONTENTS Page Abstract_________________ 69 Introduction _________________ 69 Biologic analysis____________ 69 Stratigraphic summary. _______ 70 Ages of fossils________________ 73 Comparisons with other faunas. 75 Ecological considerations___ _ 75 Geographic distribution____. 78 Summary of results ___________ 81 Systematic descriptions__ _. 82 Literature cited____________ 92 Index_____________________ 95 ILLUSTRATIONS [Plates &-13 follow Index] PLATE 8. Inoceramus and Gryphaea 9. Aucella 10. Amaltheus, Dactylioceras, "Arietites," Phylloceras, and Posidonia 11. Ludwigella, Dactylioceras, and Harpoceras. 12. Pseudocadoceras, Arcticoceras, Amoeboceras, Tmetoceras, Coeloceras, and Pseudolioceras 13. Reineckeia, Erycites, and Cylindroteuthis. Page FIGXTKE 20. Index map showing Jurassic fossil collection localities in northern Alaska. -

Earliest Known Lepisosteoid Extends the Range of Anatomically Modern Gars to the Late Jurassic Received: 25 September 2017 Paulo M

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Earliest known lepisosteoid extends the range of anatomically modern gars to the Late Jurassic Received: 25 September 2017 Paulo M. Brito1, Jésus Alvarado-Ortega2 & François J. Meunier3 Accepted: 2 December 2017 Lepisosteoids are known for their evolutionary conservatism, and their body plan can be traced at Published: xx xx xxxx least as far back as the Early Cretaceous, by which point two families had diverged: Lepisosteidae, known since the Late Cretaceous and including all living species and various fossils from all continents, except Antarctica and Australia, and Obaichthyidae, restricted to the Cretaceous of northeastern Brazil and Morocco. Until now, the oldest known lepisosteoids were the obaichthyids, which show general neopterygian features lost or transformed in lepisosteids. Here we describe the earliest known lepisosteoid (Nhanulepisosteus mexicanus gen. and sp. nov.) from the Upper Jurassic (Kimmeridgian – about 157 Myr), of the Tlaxiaco Basin, Mexico. The new taxon is based on disarticulated cranial pieces, preserved three-dimensionally, as well as on scales. Nhanulepisosteus is recovered as the sister taxon of the rest of the Lepisosteidae. This extends the chronological range of lepisosteoids by about 46 Myr and of the lepisosteids by about 57 Myr, and flls a major morphological gap in current understanding the early diversifcation of this group. Actinopterygians, or ray-finned fishes, are the largest group among extant gnathostoms vertebrates. Today actinopterygians are represented by three major clades: Cladistia (bichirs and rope fsh), with at least 16 species, Chondrostei (sturgeons and paddle fshes), with about 30 species, and Neopterygii, formed by the Teleostei, with about 30,000 species and the Holostei with eight species: one halecomorph (bowfn) and 7 ginglymodians (gars)1. -

2. General Index

Downloaded from http://pygs.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 29, 2021 2. General Index abandoned river courses. Vale of York 40,223-32 anhydrite 50.78.79,81,86,88.143-54 Abbey Crags, Knaresborough Gorge 46,290 Anisocardiu tenera (Antiquicyprina) loweana 39, 117, 130, 131.738-9 Acadian 46,175 ff.; 50,255-65 anisotropy of vitrinites 39,515-26 acanthite 46,135 ankerite 50,87 Acanthodiacrodium cf. simplex 42,412-3 annelida, in Yorkshire Museum 41,402 Acanthodiacrodium rotundatum 45.124 antimony, trace element in galena 44,153 Acanthodiacrodium cf. tumidum 45,124 apatite 44,438 Acanthopleuroceras sp. 42, 152-3 apatite fission-track palaeotemperatures. north-west England 50,95-9 accretionary lapilli, Cwm Clwyd Tuff 39,201,206-7,209,215-6 Apatocythere (Apatocythere) simulans 45, 243 Acheulian handaxes 41,89,94-5 Apedale Fault 50. 196," 198 acid intrusions, Ordovician and Caledonian, geochemical characteristics aplites. Whin Sill 47,251 of 39,33-57 Apollo's Coppice, Shropshire 50,193 acritarchs. Arenig 42. 405 Arachinidiuin smithii 42, 213 acritarchs, Ordovician 47,271-4 Araucarites phillipsii 45,287 acritarchs,Tremadoc 38 45-55; 45,123-7 archaeology, Lincolnshire 41.75 ff. Actinocamax plenus 40,586 Arcomva unioniformis 39.117.133, 134, 138 Acton Reynald Hall, Shropshire 50,193,198,199,200,202,204 Arcow"45,19ff.' adamellite (Threlkeld Microgranite) 40,211-22 Arcow Wood Quarry 39,169,446,448,455,459,470-1 aegirine 44,356 arctic-alpine flora. Teesdale 40.206 aeolian deposition, Devensian loess 40,31 ff. Arenicolites 41,416,436-7 aeolian deposition. Permian 40,54.55 Arenobulirnina advena 45,240 aeolian sands, Permian 45, 11-18 Arenobulimina chapmani 45,240 aeolian sedimentation, Sherwood Sandstone Group 50,68-71 Arenobulirnina macfadyeni 45, 240 aeromagnetic modelling, west Cumbria 50,103-12 arfvedsonite 44,356 aeromagnetic survey, eastern England 46,313,335—41 argentopyrite 46, 134-5 aeromagnetic survey, Norfolk 46.313 Arniocreas fulcaries 42, 150-1 Africa, North, Devonian of 40,277-8 arsenic 44,431 ff. -

Comments on the Identification of Ammonites Planula Hehl in Zieten, 1830 (Upper Jurassic, SW Germany)

VOLUMINA JURASSICA, 2017, XV: 1–16 DOI: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.3920 Comments on the identification of Ammonites planula Hehl in Zieten, 1830 (Upper Jurassic, SW Germany) Günter SCHWEIGERT1, Horst KUSCHEL2 Key words: Ammonoidea, Late Jurassic, Oxfordian, Kimmeridgian, Ataxioceratinae, Idoceratinae, taxonomy. Abstract. Ammonites planula Hehl in Zieten, 1830 is the type species of the Late Jurassic ammonite genus Subnebrodites Spath, 1925 and the index species of the well-established Planula Zone of the Submediterranean Province. Recently, Enay and Howarth (2017) classified this stratigraphically important ammonite species as a ʻnomen dubiumʼ and considered it to be the possible macroconch counterpart of Idoceras balderum (Oppel, 1863). These authors claimed “Subnebrodites planula Spath, 1925” instead of Ammonites planula (Hehl in Zieten, 1830) to be the type species of Subnebrodites. However, their nomenclatorial acts are based on erroneous assumptions. For future taxonomic stability we here propose a neotype for Ammonites planula (Hehl in Zieten, 1830) and a lectotype for Ammonites planula gigas Quenstedt, 1888. In addition, dimorphism within the stratigraphically much younger Idoceras balderum (Oppel) is demonstrated showing that there is no morphological resemblance and no closer relationship with Ammonites planula (Hehl in Zieten, 1830). INTRODUCTION Abbreviations: HT = holotype; [m] = microconch; [M] = macroconch; GPIT = Institut für Geowissenschaften, Uni- Recently, Enay and Howarth (2017) classified the com- versity of Tübingen, Germany;