Improving Administrative Redress in Jersey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PREHISTORIC JERSEY People and Climate of the Ice Age

PREHISTORIC JERSEY People and climate of the Ice Age Lesson plan Fact sheets Quiz sheets Story prompts Picture sheets SUPPORTED BY www.jerseyheritage.org People and climate of the Ice Age .............................................................................................................................................................................. People and climate of plan the Ice Age Lesson Introduction Lesson Objectives Tell children that they are going to be finding To understand that the Ice out about the very early humans that lived during Age people were different the Ice Age and the climate that they lived in. species. Explain about the different homo species of To understand there are two main early humans we study, early humans and what evidence there is for this. Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens. Discuss what a human is and the concept of To develop the appropriate evolution. use of historical terms. To understand that Jersey has Ask evidence of both Neanderthals How might people in the Ice Age have lived? and Early Homo Sapiens on the Where did they live? island. Who did they live with? How did they get food and what clothes did they Expected Outcomes wear? Why was it called the Ice Age? All children will be able to identify two different sets of What did the landscape look like? people living in the Ice Age. Explain that the artefacts found in Jersey are Most children will able to tools made by people and evidence left by the identify two different sets of early people which is how they can tell us about people living in the Ice Age and the Ice Age. describe their similarities and differences. Some children will describe two different sets of people Whole Class Work living in the Ice Age, describe Read and discuss the page ‘People of the their similarities and differences Ice Age’ which give an overview of the Ice Age and be able to reflect on the people and specifically the Neanderthals and evolution of people according Homo Sapiens. -

Public Services Ombudsmen. This Consultation

The Law Commission Consultation Paper No 196 PUBLIC SERVICES OMBUDSMEN A Consultation Paper ii THE LAW COMMISSION – HOW WE CONSULT About the Law Commission The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are: The Rt Hon Lord Justice Munby (Chairman), Professor Elizabeth Cooke, Mr David Hertzell, Professor David Ormerod1 and Miss Frances Patterson QC. The Chief Executive is: Mr Mark Ormerod CB. Topic of this consultation This consultation paper deals with the public services ombudsmen. Impact assessment An impact assessment is included in Appendix A. Scope of this consultation The purpose of this consultation is to generate responses to our provisional proposals. Duration of the consultation We invite responses from 2 September 2010 to 3 December 2010. How to respond By email to: [email protected] By post to: Public Law Team, Law Commission, Steel House, 11 Tothill Street, London, SW1H 9LJ Tel: 020-3334-0262 / Fax: 020-3334-0201 If you send your comments by post, it would be helpful if, wherever possible, you could send them to us electronically as well (for example, on CD or by email to the above address, in any commonly used format. After the consultation In the light of the responses we receive, we will decide our final recommendations and we will present them to Parliament. It will be for Parliament to decide whether to approve any changes to the law. Code of Practice We are a signatory to the Government’s Code of Practice on Consultation and carry out our consultations in accordance with the Code criteria (set out on the next page). -

US Senate Final

Senate Finance Committee Hearing ”Offshore Tax Evasion: Stashing Cash Overseas” 111 May 3, 2007 Statement for the Hearing Record Submitted by: Richard Murphy FCA 222 (((Visiting(Visiting Fellow, Centre for Global Political EconomEconomy,y, University of Sussex, UK ))) Prof Prem Sikka 333 (Professor of Accounting, University of Essex, UK) Prof Ronen Palan 444 (Professor of International Relations and Politics, University of Sussex, UK) Prof Sol Picciotto 555 (Professor of Law, University of Lancaster, UK) Alex Cobham 666 (Supernumerary fellow in Economics at St Anne's College, Oxford, UKUK)))) John Christensen 777 (Director, International secretariat, Tax Justice Network 888))) 1 http://www.senate.gov/~finance/sitepages/hearing050307.htm accessed 18-6-07 2 http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Documents//RichardMurphycvJuly2006.pdf accessed 18-6-07 3 http://www.essex.ac.uk/afm/staff/sikka.shtm accessed 18-6-07 4 http://www.sussex.ac.uk/irp/profile17282.html accessed 18-6-07 5 http://www.lancs.ac.uk/fss/law/staff/picciotto.htm accessed 18-6-07 6 http://www.policyinnovations.org/innovators/people/data/07512 accessed 18-6-07 7 John Christensen is a development economist and an expert on tax havens. Based at the New Economics Foundation in London, he is international coordinator of the Tax Justice Network. 8 http://www.taxjustice.net/cms/front_content.php?idcat=2 accessed 18-6-07 1 Jersey ––– still a tax haven Chairman Baucus, Ranking Member Grassley, Members of the Committee, we are honoured to provide you with this written testimony on the subject of offshore tax evasion. This testimony is submitted in the light of Bills S. -

Języki Regionalne I Mniejszościowe Wielkiej Brytanii

biuro analiz, dokumentacji i korespondencji Języki regionalne i mniejszościowe Wielkiej Brytanii Opracowania tematyczne OT–677 warszawa 2020 © Copyright by Kancelaria Senatu, Warszawa 2020 Biuro Analiz, Dokumentacji i Korespondencji Dyrektor – Agata Karwowska-Sokołowska tel. 22 694 94 32, fax 22 694 94 28, e-mail: [email protected] Wicedyrektor – Danuta Antoszkiewicz tel. 22 694 93 21, e-mail: [email protected] Dział Analiz i Opracowań Tematycznych tel. 22 694 92 04, fax 22 694 94 28 Opracowanie graficzno-techniczne Centrum Informacyjne Senatu Dział Edycji i Poligrafii Kancelaria Senatu styczeń 2020 dr Andrzej Krasnowolski Dział Analiz i Opracowań Tematycznych Biuro Analiz, Dokumentacji i Korespondencji Języki regionalne i mniejszościowe Wielkiej Brytanii I. Uwagi wstępne Istnienie lokalnych mniejszościowych języków na terytorium każde- go państwa uwarunkowane jest jego historią. W większości państw obok języka narodowego występują języki dawnych grup etnicznych, mniejszości narodowych oraz języki regionalne, którymi posługują się mieszkańcy konkretnego terytorium – języki niewystępujące na innych obszarach państwa. Języki takie mogą posiadać lokalny status prawny lub mogą być jego pozbawione, a ich przetrwanie zawsze zależy od stop- nia użytkowania ich w środowiskach rodzinnych. Zjednoczone Królestwo Wielkiej Brytanii i Irlandii Północnej w jego zachodnioeuropejskiej części tworzy archipelag wysp różnej wielkości, z których największa to Wielka Brytania, na której położone są Anglia, Walia i Szkocja; -

202-03-55145 Company Name Address 1-2-1 MENTORING 1-2-1

Freedom of Information Request Ref: 202-03-55145 Company Name Address 1-2-1 MENTORING 1-2-1 MENTORING , 14 HILL STREET , ST. HELIER , JE2 4UA ACET JERSEY 6 ACET JERSEY , PLAISANCE TERRACE , LA ROUTE DU FORT , ST. SAVIOUR , JE2 7PA ACREWOOD DAY NURSERY ACREWOOD DAY NURSERY , PETIT MENAGE , BELVEDERE HILL , ST. SAVIOUR , JE2 7RP ADVANCE PLUS SOCIAL SECURITY DEPARTMENT , PHILIP LE FEUVRE HOUSE, LA MOTTE STREET , ST. HELIER , JE4 8PE ADVANCE TO WORK SOCIAL SECURITY DEPARTMENT , PHILIP LE FEUVRE HOUSE, LA MOTTE STREET , ST. HELIER , JE4 8PE AGE CONCERN JERSEY AGE CONCERN , 37 WINDSOR HOUSE , VAL PLAISANT , ST. HELIER , JE2 4TA ALL CARE JERSEY LTD ALL CARE JERSEY LTD , 7 COMMERCIAL BUILDINGS , ST. HELIER , JE2 3NB AUTISM JERSEY TOP FLOOR , 2 BRITANNIA PLACE OFFICES , BATH STREET , ST. HELIER , JE2 4SU BAILIFF'S CHAMBERS - SOJ003 ROYAL COURT HOUSE, , ROYAL SQUARE, , ST. HELIER , JE11BA Freedom of Information Request Ref: 202-03-55145 BEAULIEU CONVENT SCHOOL BEAULIEU PRIMARY SCHOOL , WELLINGTON ROAD , ST. HELIER , JE2 4RJ BRIGHTER FUTURES BRIGHTER FUTURES , THE BRIDGE , LE GEYT ROAD , JE2 7NT BRIG-Y-DON CHILDREN'S CHARITY LARN A LOD , LA RUE DU COIN , GROUVILLE , JE3 9QR CAMBRETTE NURSING SERVICES 1ST FLOOR OFFICE , 17 QUEEN STREET , ST. HELIER , JE2 4WD CARING HANDS LTD SANCTUARY HOUSE , HIGH STREET , ST AUBIN , ST. BRELADE , JE3 8BZ CENTRE POINT TRUST CENTRE POINT TRUST , LE HUREL , LA POUQUELAYE , ST. HELIER , JE2 3FW CHARLIE FARLEY'S NURSERIES CHARLIE FARLEY'S NURSERIES , FAIRFIELDS , NORCOTT ROAD , ST. SAVIOUR , JE2 7PS CHILD CARE REGISTRATION EDUCATION, SPORT & CULTURE , PO BOX 142, HIGHLANDS COLLEGE , LA RUE DU FROID VENT , ST. -

How the Government of Jersey Delivers Online Services with Digital ID

50% of adults have created Residents can now file a Yoti account a tax return online How the Government of Jersey delivers online services Company with digital ID The Government of Jersey Industry Challenge Government In 2017, the Government of Jersey released a tender for a digital Solution identity scheme to enable them to verify and authenticate citizens Digital ID online. They wanted to deliver online public services through the one.gov.je portal, which would span social security, health and social Implementation services, income tax and driving licence applications. Web SDK The winning provider would have to deliver an accessible tool that people could use to prove their identity online and securely Jersey is a UK crown authenticate themselves across platforms and services. A key objective dependency in the Channel was for it to be suitable for use in the private sector, given this had Islands with a population of been a failure of other government digital identity projects. The around 108,000 people. solution had to be citizen-centric and ready for a government-wide roll out as quickly as possible. “A secure digital ID system is fundamental to providing integrated, online services and supporting the modernisation of Jersey’s public sector. Yoti’s technology will enable islanders to prove who they are so they can safely access government services online.” Senator Ian Gorst - Former Chief Minister of Jersey Solution After a competitive procurement process, the Government of Jersey selected our digital identity app for its seamless digital experience and reusability across public and private sectors. The app is free to download and makes it easy for anyone to create a digital ID by taking a scan of their ID document and a biometric selfie. -

The Story of New Jersey

THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY HAGAMAN THE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING COMPANY Examination Copy THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY (1948) A NEW HISTORY OF THE MIDDLE ATLANTIC STATES THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY is for use in the intermediate grades. A thorough story of the Middle Atlantic States is presented; the context is enriohed with illustrations and maps. THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY begins with early Indian Life and continues to present day with glimpses of future growth. Every aspect from mineral resources to vac-| tioning areas are discussed. 160 pages. Vooabulary for 4-5 Grades. List priceJ $1.28 Net price* $ .96 (Single Copy) (5 or more, f.o.b. i ^y., point of shipment) i^c' *"*. ' THE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING COMPANY Linooln, Nebraska ..T" 3 6047 09044948 8 lererse The Story of New Jersey BY ADALINE P. HAGAMAN Illustrated by MARY ROYT and GEORGE BUCTEL The University Publishing Company LINCOLN NEW YORK DALLAS KANSAS CITY RINGWOOD PUBLIC LIBRARY 145 Skylands Road Ringwood, New Jersey 07456 TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW.JERSEY IN THE EARLY DAYS Before White Men Came ... 5 Indian Furniture and Utensils 19 Indian Tribes in New Jersey 7 Indian Food 20 What the Indians Looked Like 11 Indian Money 24 Indian Clothing 13 What an Indian Boy Did... 26 Indian Homes 16 What Indian Girls Could Do 32 THE WHITE MAN COMES TO NEW JERSEY The Voyage of Henry Hudson 35 The English Take New Dutch Trading Posts 37 Amsterdam 44 The Colony of New The English Settle in New Amsterdam 39 Jersey 47 The Swedes Come to New New Jersey Has New Jersey 42 Owners 50 PIONEER DAYS IN NEW JERSEY Making a New Home 52 Clothing of the Pioneers .. -

The Parliamentary Ombudsman: Firefighter Or Fire-Watcher?

12 The Parliamentary Ombudsman: Firefi ghter or fi re-watcher? Contents 1. In search of a role 2. The PCA’s offi ce 3. From maladministration to good administration 4. Firefi ghting or fi re-watching? (a) The small claims court (b) Ombudsmen and courts (c) Fire-watching: Inspection and audit 5. Inquisitorial procedure (a) Screening (b) Investigation (c) Report 6. The ‘Big Inquiry’ (a) Grouping complaints: The Child Support Agency (b) Political cases 7. Occupational pensions: Challenging the ombudsman 8. Control by courts? 9. Conclusion: An ombudsman unfettered? 1. In search of a role In Chapter 10, we considered complaints-handling by the administration, set- tling for a ‘bottom-up’ approach. Th is led us to focus on proportionate dispute resolution (PDR) and machinery, such as internal review, by which complaints can be settled before they ripen into disputes. In so doing, we diverged from the ‘top-down’ tradition of administrative law where tribunals are seen as court substitutes. We returned to the classic approach in Chapter 11, looking at the recent reorganisation of the tribunal service and its place in the administrative justice system. We saw how the oral and adversarial tradition of British justice was refl ected in tribunal procedure and considered the importance attached to impartiality and independence, values now protected by ECHR Art. 6(1). We, 529 The Parliamentary Ombudsman: Firefi ghter or fi re-watcher? however, argued that recent reshaping of the tribunal system left unanswered key questions about oral and adversarial proceedings and whether they are always the most appropriate vehicle for resolving disputes with the administra- tion. -

The 22Nd Jersey Youth Assembly Convened on 19Th March 2019 at 1.30 P.M

The 22nd Jersey Youth Assembly convened on 19th March 2019 at 1.30 p.m. in the States Chamber, under the Presidency of the Bailiff, Sir William James Bailhache _________________ The following members were present: Lily Dobber Storm Rothwell Jenna Stocks Emma Pallent James Dunn Sam Wright Ross Laurent Jacob Burgin Patryk Lalka Morgan Brady Jemima Butler Eoghan Spillane Rhian Murphy Heather Orpin Aimee Hugh Rosie Nicholls Clara Garrood Max Johnson Sean Hughes Sam Gibbins Thomas Glover Jennifer Luiz Evan Campbell Stella Greene Fynn Mason Jennifer Cullen Christie Lyons Romy Smith The following members were en défaut: Philip Romeril Thomas Eva Christopher Stride Thomas Bowden Tanguy Billet Masters Scott Douglas Lysander Mawby Matthew Mourant Liam O'Connell Jack Rive Oscar Shurmer Holly Clark Alice O’Connell States Members present: Senator John Le Fondré, Chief Minister Senator Ian Gorst, Minister for External Relations Senator Tracey Vallois, Minister for Education Senator Sam Mézec, Minister for Children and Housing Deputy Kevin Lewis, Minister for Infrastructure Deputy Montfort Tadier of St. Brelade, Assistant Minister for Economics, Tourism, Sport and Culture Deputy Susie Pinel of St. Clement, Minister for Treasury and Resources Deputy Richard Renouf of St. Ouen, Minister for Health and Social Services Deputy Russell Labey of St. Helier, Chairman of the Privileges and Procedures Committee _________________ Prayers were read in French by Miss Rosie Nicholls of Jersey College for Girls _________________ COMMUNICATIONS BY THE BAILIFF The Bailiff of Jersey, Sir William James Bailhache, welcomed students to the 22nd Annual Jersey Youth Assembly. QUESTIONS Storm Rothwell of Jersey College for Girls asked a question of Senator Tracey Vallois, Minister for Education regarding the range of issues covered by the PSHE curriculum. -

48 St Saviour Q3 2020.Pdf

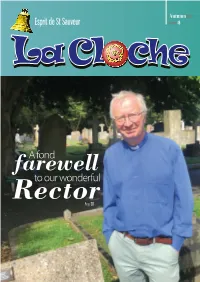

Autumn2020 Esprit de St Sauveur Edition 48 farewellA fond Rectorto our wonderful Page 30 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Autumn 2020 St Saviour Parish Magazine p3 From the Editor Featured Back on Track! articles La Cloche is back on track and we have a full magazine. There are some poems by local From the Constable poets to celebrate Liberation and some stories from St Saviour residents who were in Jersey when the Liberation forces arrived on that memorable day, 9th May 1945. It is always enlightening to read and hear of others’ stories from the Occupation and Liberation p4 of Jersey during the 1940s. Life was so very different then, from now, and it is difficult for us to imagine what life was really like for the children and adults living at that time. Giles Bois has submitted a most interesting article when St Saviour had to build a guardhouse on the south coast. The Parish was asked to help Grouville with patrolling Liberation Stories the coast looking for marauders and in 1690 both parishes were ordered to build a guardhouse at La Rocque. This article is a very good read and the historians among you will want to rush off to look for our Guardhouse! Photographs accompany the article to p11 illustrate the building in the early years and then later development. St Saviour Battle of Flowers Association is managing to keep itself alive with a picnic in St Paul’s Football Club playing field. They are also making their own paper flowers in different styles and designs; so please get in touch with the Association Secretary to help with Forever St Saviour making flowers for next year’s Battle. -

Migration from Jersey to New Zealand in the 1870S

Migration from Jersey to New Zealand in the 1870s Version 3.0 Draft for comment, June 2019 Mark Boleat Comments welcome. Please send to [email protected] MIGRATION FROM JERSEY TO NEW ZEALAND IN THE 1870’S 1 Contents Introduction 3 1. The early migrants 4 2. The context for the 1872-1875 migration 6 3. The number of migrants 11 4. Why migration from Jersey to New Zealand was so high 15 5. The mechanics of the emigration 19 6. Characteristics of the emigrants 27 7. Where the emigrants settled 31 8. Prominent Jersey people and Jersey links in New Zealand 34 9. The impact on Jersey 40 Appendix 1 – sailings to New Zealand with Jersey residents, 42 1872-75– list of Jersey emigrants Appendix 2 – list of Jersey emigrants to New Zealand, 1872-75 45 References 56 MIGRATION FROM JERSEY TO NEW ZEALAND IN THE 1870’S 2 Introduction Over 500 people emigrated from Jersey to New Zealand between 1873 and 1874, and over the same period some 300 emigrated to Australia. By any standards this was mass migration comparable with the mass migration into Jersey in the 1830s and 1840s. Why and how did this happen, what sort of people were the emigrants and where did they settle in New Zealand? This paper seeks to explore these issues in respect of the emigration to New Zealand, although much of the analysis would be equally applicable to the emigration to Australia. The paper could be written only because of the excellent work by Keith Vautier in compiling a comprehensive database of 900 Channel Islanders who migrated to Australia and New Zealand. -

The Island Identity Policy Development Board Jersey's

The Island Identity Policy Development Board Jersey’s National and International Identity Interim Findings Report 1 Foreword Avant-propos What makes Jersey special and why does that matter? Those simple questions, each leading on to a vast web of intriguing, inspiring and challenging answers, underpin the creation of this report on Jersey’s identity and how it should be understood in today’s world, both in the Island and internationally. The Island Identity Policy Development Board is proposing for consideration a comprehensive programme of ways in which the Island’s distinctive qualities can be recognised afresh, protected and celebrated. It is the board’s belief that success in this aim must start with a much wider, more confident understanding that Jersey’s unique mixture of cultural and constitutional characteristics qualifies it as an Island nation in its own right. An enhanced sense of national identity will have many social and cultural benefits and reinforce Jersey’s remarkable community spirit, while a simultaneously enhanced international identity will protect its economic interests and lead to new opportunities. What does it mean to be Jersey in the 21st century? The complexity involved in providing any kind of answer to this question tells of an Island full of intricacy, nuance and multiplicity. Jersey is bursting with stories to tell. But none of these stories alone can tell us what it means to be Jersey. In light of all this complexity why take the time, at this moment, to investigate the different threads of what it means to be Jersey? I would, at the highest level, like to offer four main reasons: First, there is a profound and almost universally shared sense that what we have in Jersey is special.