Answers in the Wind: Using Local Weather Studies for Family History Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DEVIL's DYKE, NEWMARKET. Newmarketand

THE DEVIL'S DYKE, NEWMARKET. {READ Arm 13, 1850.] NEWMARKETandits neighbourhood possessed, till within a few years, numerous evidencesof the warlike races which antiently occupied our Island ; but many of the tumuli which studded the country, with fragments of trackways and embankments, have been cleared away, without, it is much to be regretted, even a note of their contents, form, or precise locality. Most remarkable earthworks, however, extending from the woody uplands on one side to the wide expanse of fen on the other, remain to attest the presence and the labours of contending races Camden enumerates five almost parallel dykes or ditches. The first, called Brent Ditch, between Melbourne and Foulmire ; the second about 5 miles long, running from Hinxton, by Hildersham, to Horseheath ; the third,.called Fleam (Flight) Dyke, or from the length of its course, Seven Mile Dyke, from Balsham to Fen Ditton ; the fourth, the greatest and most entire, popularly called the Devil's Dyke, from Woodditton to Reach, a distance of 7 or 8 miles ; and a fifth, the least of all, " shewethe itselfe two miles from hence, betweene Snailwell and Moulton." The courses of the four first of these ditches are shewn on Lysons's map of Cambridge- shire. Brent or Brant Ditch, says that author, is a slight work of the kind, proceeding from Heydon, in Essex, *pointing nearly to Barrington, continuing over part of . Foulmire, till it ends in a piece of boggy ground. The. "Secondditch is seen about a mile south of Bournbridge, lying upon declining ground between Abingdon Wood and Pampisworth, pointing towards Cambridge. -

Fulbourn Site Assessment Proforma

South Cambridgeshire Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) Report August 2013 Appendix 7i: Assessment of 2011 'Call for Sites' SHLAA sites Index of Fulbourn Site Assessment Proforma Site Site Address Site Capacity Page Number Land at Fulbourn Old Drift (south of Site 037 Cambridge Road and north of Shelford 921 dwellings 766 Road), Fulbourn Site 038 Land north of Cambridge Road, Fulbourn 166 dwellings 775 Site 074 Land off Station Road, Fulbourn 186 dwellings 783 Site 108 Land south of Hinton Road, Fulbourn 52 dwellings 794 Land to the South of Fulbourn Old Drift & Site 109 78 dwellings 802 Hinton Road, Fulbourn Site 136 Land at Balsham Road, Fulbourn 62 dwellings 810 Land between Teversham Road and Cow Site 162 92 dwellings 818 Lane, Fulbourn Land at east of Court Meadows House, Site 213 166 dwellings 829 Balsham Road, Fulbourn Site 214 Land off Home End, Fulbourn 14 dwellings 837 Site 245 Bird Farm Field, Cambridge Road, Fulbourn 85 dwellings 845 SHLAA (August 2013) Appendix 7i – Assessment of 2011 ‘Call for Sites’ SHLAA sites Minor Rural Centre Fulbourn Page 765 South Cambridgeshire Local Development Framework Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) Site Assessment Proforma Proforma July 2012 Created Proforma Last July 2013 Updated Location Fulbourn Site name / Land at Fulbourn Old Drift (south of Cambridge Road and north of address Shelford Road), Fulbourn Category of A village extension i.e. a development adjoining the existing village site: development framework boundary Description of promoter’s 3,050 dwellings with public open space proposal Site area 76.78 ha. (hectares) Site Number 037 The site lies to the south of Cambridge Road and north of Shelford Road on the south western edge of Fulbourn. -

Locations of Horseheath Records

Locations of Horseheath records Part of Horseheath Village Archives Locations of Horseheath records Cambridgeshire Archives and Local Studies Office Formerly Cambridge Record Office, this holds census, church and parish records along with over 300 other items concerning Horseheath. It is located in the Cambridgeshire County Council Offices, Shire Hall, Castle Street, Castle Hill, Cambridge CB3 0AP Tel.01223 699 399 The Cambridgeshire Collection This is located within the Cambridge Central Library and contains a wide variety of information relating to Cambridgeshire and its people. It includes books, pamphlets, magazines, maps from 1574, illustrations from the 17 th c, newspapers from 1762, press cuttings from 1960 and ephemera of all kinds. The Cambridge Antiquarian Society Photographic Archive is held in the Cambridgeshire Collection, as is the studio portrait archive of the former Cambridge photographers J Palmer Clarke and Ramsey and Muspratt. Family historians have access to many sources listing former residents of the county; directories, electoral rolls, poll books, parish register transcripts, etc. Cambridge University Library List follows. Cemeteries The Monumental Inscriptions in the graveyard of All Saints from the 15th century-1981 are recorded in Cambridgeshire Archives and Local Studies in the Council Offices, Shire Hall, Castle Hill. A copy of the original manuscript of ‘Inscriptions on gravestones and internal monuments’, by Catherine Parsons, 1897 appears in the @all Saints’ Church sewction of Horseheath Village Archives. Census The Census Records from 1841-1911 can be found in the Cambridgeshire Archives and Local Studies Office and at the Family Records Centre in London (see below). The 1881 Census is available in searchable form on www.familysearch.org. -

The Cambridge Spring Dash

The Cambridge Spring Dash 100 — 2021 Sheet 1 of 2 The Cambridge Spring Dash 100 1 Cambridge to Meesden 44km L from départ in Girton towards Cambridge Organised by Nick Wilkinson, 07500 787785. SO @ mrbt no $ then L @ T $ CAMBRIDGE 1.7 This Audax UK event takes place on Saturday 16 March 2019, starting at 8:00am. SO @ all TLs to descend Castle Hill to … Control opening and closing times are shown SO @ TL, SO @ mrbt, thru restriction to R @ T/X on the brevet. opp Round Church no $ [St John’s St] 4.3 If you decide to abandon the ride, please let us SO thru bollards by Gt St Mary’s Church know by text or phone on 07500 787785, so that i King’s College & Chapel on RHS we don’t have to wait for you to ‘not arrive’! L @ T eff SO [Trumpington Rd] This event is run under the governance of Audax UK and is undertaken as a private excursion on SO @ double-mrbt $ Ring Road, Haverhill 5.9 public roads. This route is advisory. SO @ TL $ Ring Road SO @ TL $ TRUMPINGTON SO @ TL, past Shell Garage on RHS then … L @ TL $ THE SHELFORDS 9.1 For more audax events around Cambridge, Soon SO @ TL $ THE SHELFORDS visit our website at www.camaudax.uk. In 2km R $ WHITTLESFORD [High St] 11.9 1 3 2 4 In Little Shelford, bear sharp L 13.2 Key to symbols and abbreviations Thru Whittlesford to … Distances in kilometres from start of each stage SO @ STGX (R+L) $ DUXFORD [Moorfield Rd] R, L, RHS, LHB—Right, Left, Right/left-hand side/bend !CARE BUSY! 18.7 SO—Straight on @—At Cont thru Duxford to Ickleton where … thru—Through cont—Continue R on LH-bend/[x] in Ickleton’s -

Cambridgeshire Estimated CO2 Emissions 2017 V2 Per Capita

Cambridgeshire Estimated CO2 emissions 2017 v2 Per capita Est 2016 Industry, Commercial Indirect Indirect Local authority name Village/Town/Ward Population Total agriculture and agriculture emissions Transport not industry (t) industry not Domestic Grand Cambridge Abbey 9,990 21.1 13.3 8.6 39.9 82.8 Arbury 9,146 19.3 12.2 7.9 36.5 75.8 Castle 9,867 20.8 13.1 8.5 39.4 81.8 Cherry Hinton 8,853 18.7 11.8 7.6 35.3 73.4 Coleridge 9,464 20.0 12.6 8.2 37.8 78.5 East Chesterton 9,483 20.0 12.6 8.2 37.8 78.6 King's Hedges 9,218 19.5 12.3 7.9 36.8 76.4 Market 7,210 15.2 9.6 6.2 28.8 59.8 Newnham 7,933 16.7 10.6 6.8 31.6 65.8 Petersfield 8,402 17.7 11.2 7.2 33.5 69.7 Queen Edith's 9,203 19.4 12.2 7.9 36.7 76.3 Romsey 9,329 19.7 12.4 8.0 37.2 77.4 Trumpington 8,101 17.1 10.8 7.0 32.3 67.2 West Chesterton 8,701 18.4 11.6 7.5 34.7 72.2 Cambridge Total 124,900 263.6 166.2 107.7 498.3 1,035.8 6.2 East Cambridgeshire Ashley 794 2.3 1.2 2.6 3.3 9.3 Bottisham 2,332 6.7 3.5 7.5 9.7 27.4 Brinkley 415 1.2 0.6 1.3 1.7 4.9 Burrough Green 402 1.2 0.6 1.3 1.7 4.7 Burwell 6,692 19.2 9.9 21.6 27.8 78.5 Cheveley 2,111 6.1 3.1 6.8 8.8 24.8 Chippenham 548 1.6 0.8 1.8 2.3 6.4 Coveney 450 1.3 0.7 1.4 1.9 5.3 Downham 2,746 7.9 4.1 8.8 11.4 32.2 Dullingham 814 2.3 1.2 2.6 3.4 9.5 Ely 21,484 61.8 31.9 69.2 89.2 252.2 Fordham 2,876 8.3 4.3 9.3 11.9 33.8 Haddenham 3,547 10.2 5.3 11.4 14.7 41.6 Isleham 2,522 7.3 3.7 8.1 10.5 29.6 Kennett 374 1.1 0.6 1.2 1.6 4.4 Kirtling 347 1.0 0.5 1.1 1.4 4.1 Littleport 9,268 26.6 13.8 29.9 38.5 108.8 Lode 968 2.8 1.4 3.1 4.0 11.4 Mepal 1,042 -

Lent Term 1998 Welcome Back to the Rambling Club! We Once Again Invite You to Leave the City for a Few Hours This Term, and Enjoy the Surrounding Countryside with Us

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY RAMBLING CLUB Lent Term 1998 Welcome back to the Rambling Club! We once again invite you to leave the city for a few hours this term, and enjoy the surrounding countryside with us. The pace of our walks is generally easy, as our primary aim is to relax and appreciate the local scenery and villages. We usually stop at a village pub en route, but you should bring a packed lunch and liquid refreshment anyway. Strong boots and waterproof clothing are also recommended. There is no need to sign up in advance to join a walk, and your only expense is the bus/train fare to the start point for each ramble, plus our £1 annual membership fee. In addition to our walks this term, we look forward to seeing you at our Formal Hall gatherings in Wolfson and Trinity! Saturday 24th January Balsham − Great Chesterford 8½ miles Contact: Aidan Travelling south−west from Balsham, we climb to the top of Rivey Hill, near Linton. After stopping for lunch, we continue across undulating farmland towards Great Chesterford. Out: 1030 bus to Balsham Return: 1540 train from Great Chesterford, arriving back at 1557 Sunday 1st February Great Barford circular 10 miles Contact: Matthew This walk explores the villages and rolling countryside north−east of Bedford. Starting from Great Barford, we follow the River Great Ouse upstream for two miles before heading north to Renhold and Church End, where we stop for lunch. After reaching a staggering height of 70 metres (!) we return south−east to the starting point. Out: 1000 bus to Great Barford Return: 1615 bus from Great Barford, arriving back at 1650 Thursday 5th February Formal Hall at Wolfson Contact: Anshuman Places will be rather limited for this occasion, so please contact Anshuman early to reserve a place (giving your name, college, e−mail address/phone no. -

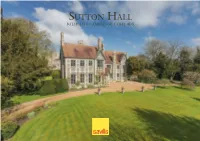

SUTTON HALL BALSHAM A4 12Pp.Indd

SUTTON HALL BALSHAM • CAMBRIDGE • CB21 4DX SUTTON HALL 13 WEST WRATTING ROAD • BALSHAM • CAMBRIDGE • CB21 4DX Cambridge 10 miles • Whittlesford Station 10.2 miles (serving London Liverpool Street) Access M11 Junction 10 (south and north) 10.6 miles; Junction 9 (south) 11.8 miles Saffron Walden 11.3 miles (All distances are approximate) A substantial Grade II listed former Rectory renovated to a high standard in 2009 Ground floor: Entrance lobby • cloaks w.c. • entrance & staircase halls • drawing room • sitting room TV room • kitchen & breakfast room • study • pantry • larder & utility room • extensive cellars Master Bedroom suite with dressing room, library/bedroom 2 and en suite bathroom 3 further bedrooms • family bathroom • shower room • 3 attic bedrooms • plant/maid’s room Brick and flint outbuildings providing garaging for up to 4 cars • boiler room and fuel stores Further outbuilding or bothy comprising garden room and wood store Delightful mature and secluded partly walled gardens and grounds In all about 2.04 acres Savills Cambridge Unex House, 132-134 Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 8PA Tel: 01223 347147 [email protected] savills.co.uk SITUATION Sutton Hall is situated at the eastern end of the attractive village of Balsham. There are good facilities in the village including a well regarded butchers, a village shop/ post office, historic parish church and primary school. Further local facilities are found within nearby Linton. Comprehensive cultural, recreational and shopping facilities are available in the centre of Cambridge 10 miles to the west. There is secondary schooling at Linton Village College together with Hills & Long Road sixth form colleges in Cambridge and renowned independent schools in both Cambridge and Saffron Walden. -

Balsham Parish Council Bus Reform Proposal October 2020 1

Balsham Parish Council Bus Reform Proposal October 2020 1. Introduction According to the 2011 Census, Balsham has a population of over 1,591. It has been identified as the least accessible ward in South Cambridge with a lack of public transport as well as the length of time it takes to access work, education, health, leisure and social activities. Around 2012, Stagecoach cut the 16a service to one bus per day. After some discussions, the timetable was adjusted so the service was to run 15 minutes earlier ensuring commuters would arrive at work on time and 25 minutes later in the afternoon. This adjustment helped commuters in the morning but not coming back home in the evenings. Just after 16a service was cut, the Big Green Bus shuttle service, the number 19, started running services during the day between Haverhill, Burrough Green, Balsham and Linton with the aim to provide transport links between towns and villages. The Parish Council recognises Balsham and the surrounding villages have the poorest public transport links with current services not working for the majority of residents. As a consequence, a survey and petition was organised at the end of 2019 to obtain information to find out if residents use the current service, how it is used, what the issues are, would a regular, reliable service be beneficial and what type of service is needed. 2. Overview Stagecoach 16a Service; There is only one bus service through the village, Stagecoach’s 16a service originating from Great Thurlow. The earliest it departs Balsham is 7.35am and leaves Cambridge at 4.40pm. -

Property Insight

PROPERTY INSIGHT SUMMER 2019 HOMES TO BUY & LET, LIFESTYLE FEATURES & MORE Pages2&3_Layout 1 04/05/2019 19:35 Page 2 Cheffins Fine Art department hosts monthly ‘Interiors’ auctions at our salerooms in the heart of Cambridge. We also offer specialist sales of Fine Art, Modern Design, Silver, Jewellery and Watches, Antiquarian Books and Asian Art as well as complimentary valuations every week. cheffins.co.ukh ffins .uk 01223 213343 Visit che ns.co.uk to view our calendar of sales or call the Fine Art team on 01223 213343 3 welcomesummer2019_Layout 1 04/05/2019 16:08 Page 1 Welcome elcome to the spring/summer issue of Icknield Way, the ancient path which crosses the Property Insight magazine, our bi- region, and also a review of a beautiful garden Wannual look at homes for sale and to at Ousden, between Newmarket and Haverhill. let, alongside property news and views on the Elsewhere we have interviews with Cambridge market. Our previous three issues have been educated actor Tom Hiddleston and bestselling hugely popular with local residents and also author Victoria Hislop. For those looking to move those from further afield, so I hope that you take house, we have listed some of the best homes the time to have a look through this most recent on the market as well as providing a market magazine and enjoy what you find inside. update and focus on Newmarket and I talk Away from the property updates, this issue about who really is buying in our region at the includes a roundup of beach hotels to try this moment. -

Balsham Road, Linton WELCOME 01 INTRODUCTION

Balsham Road, Linton 01 WELCOME INTRODUCTION Gladman Developments Ltd have successfully invested in communities throughout the UK over the past 30 years, developing high quality and sustainable residential, commercial and industrial schemes. The following pages illustrate our emerging outline proposals for a new residential development on land off Balsham Road, Linton. The purpose of the public consultation process is to outline the details of the draft scheme and seek comments from the local community which will be considered before the outline planning application is lodged with South Cambridgeshire District Council. The Site The Need for Housing The Site is located on the eastern edge of the village of Linton in Cambridgeshire. The Every Council is required by Government to boost significantly A1307 Cambridge Road is the main thoroughfare through the southern part of the the supply of housing and to make planning decisions in light settlement and provides a connection to Cambridge and Haverhill, approximately of the presumption in favour of sustainable development. 17km (10.5 miles) north west and 13km (8.07 miles) to the east respectively. The Council has a demonstrable need for more housing and The Site comprises a single irregular shaped field measuring approximately 3.07 additional deliverable sites are required in order to meet this hectares. It is bound by Balsham Road to the north west and to the west by demand and maintain a five year housing supply as required by residential properties on Brinkman Road, Bawtree Crescent and Balsham Road. National Policy. CA M D B A R O I R D M G A SH SITE E AL R B O A D A LINTON 1307 Site Boundary Site Location Plan The Application A Sustainable Location Gladman Developments Ltd intends on submitting an outline planning application for up to The Site is located in a sustainable location with 65 homes to South Cambridgeshire District Council. -

These Notes Describe a Major Source of Cambridgeshire History That You Can Make Use Of, Totally Free, from Your Computer Or Tablet

These notes describe a major source of Cambridgeshire history that you can make use of, totally free, from your computer or tablet. Bit.ly/CambsCollection Cambridgeshire History on Your Computer / My Library on Your Laptop B Mike Petty For over 50 years people have helped me record the story of Cambridgeshire. They have shared their knowledge, their memories, pictures and publications. For nearly 35 years I was privileged to add these to the Cambridgeshire Collection at Cambridge Central Library, that wonderful resource established in 1855 with its books, pictures, maps, ephemera and newspaper files which is open to all. Since then I have continued to seek out Cambridgeshire information and have endeavoured to share my scant knowledge through books, talks and some 30 years of weekly and daily newspaper articles. Now I have published much of that information online for all to download and use. It is hosted on the Internet Archive website, a non-profit library of millions of free books, movies, software, music, websites, and more - www.Archive.org My own page is https://archive.org/search.phpY This is a lot to remember but the BBC Who Do You Think You Are Magazine created a shortcut which I am happy to use. Just Google bit.ly/CambsCollection There are a lot of items on the site. They include: The Albatross Inheritance: local studies libraries, by Mike Petty This detailed study of the history and arrangement of the Cambridgeshire Collection with thoughts on its future was published in Library Management, vol.6, 1985. Books and Articles A Cambridgeshire Bibliography, vol.1: books and pamphlets, by Mike Petty My detailed annotated card index to the books and pamphlets acquired by the Cambridgeshire Collection between 1855 and 1997 is now no longer available to researchers. -

Directions to Victoria House, Fulbourn

Victoria House The headquarters for NHS East of England is at Victoria House in From the A14 From the M11 From the A11 Fulbourn, a small village to the east of Cambridge. If you are arriving by train 1. Leave the A14 at junction 35, 1. From the M11 north & southbound, exit 1. From the A11 north & southbound, or coach, you will need to take a taxi or signposted for A1303 for Newmarket, at junction 11 and follow the A1309. exit at turn off signed Fulbourn, bus to Fulbourn. Cambridge and Stow Cum Quay. 2. Take the second major turning on your Balsham and Teversham. 2. At the roundabout, follow signs for right into Long Road (A1134) and then 2. Go through Fulbourn village. By Bus Cambridge (A1303). straight on over the next roundabout 3. On exiting Fulbourn, Capital Park Take the City 1 Fulbourn bus from Emanuel 3. At the next roundabout, turn left, and traffic lights. Business Park is situated on the right Street, central Cambridge or from the train following signs for Teversham, 3. Go straight on at the next roundabout. hand side after approximately 1 mile. station. The bus stops in the centre of Cherry Hinton and Fulbourn. 4. Follow Queen Edith’s Way until you see 4. Turn right into the Capital Park Business Capital Business Park then follow the signs 4. Continue to the next roundabout and the sign for Fulbourn and Cambridge Park and follow the signs for NHS East for Victoria House. turn left following signs for Fulbourn, Airport. of England. Trumpington and Addenbrooke’s.