An Australian War Requiem” and Approval to Use the Closely Guarded Anzac from the Following: Logo for This Event

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andamooka Opal Field- 0

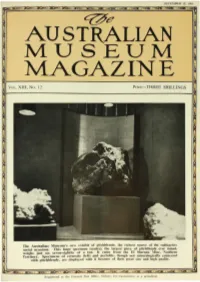

DECEMBER IS, 1961 C@8 AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM MAGAZINE VoL. XliL No. 12 Price-THREE SHILLINGS The Austra lian Museum's new exhibit of pitchblende, the richest source of the radioactive metal uranium. T his huge specimen (centre), the largest piece of pitchblende ever mined, weighs just on seven-eighths ?f a ton. 1t came. from the El S l~ eran a ~, line , Northern Territory. Specimens of ccruss1te (left) and pectohte. thOUf!h not nuneralog•cally connected with pitchblende, arc displayed with it because of their great size and high quality. Re gistered at the General Post Office, Sydney, for transmission as a peri odical. THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM HYDE PARK, SYDNEY BO ARD O F TRUSTEES PRESIDENT: F. B. SPENCER CROWN TRUSTEE: F. B. SPENCER OFFICIAL TRUSTEES: THE HON. THE CHIEF JUSTICE. THE HON. THE PRESIDENT OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL. THE HON. THE CHIEF SECRETARY. THE HON. THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL. THE HON. THE TREASURER. THE HON. THE MINISTER FOR PUBLIC WORKS. THE HON. THE MINISTER FOR EDUCATION. THE AUDITOR-GENERAL. THE PRESIDENT OF THE NEW SOUTH WALES MEDICAL BOARD. THE SURVEYOR-GENERAL AND CHIEF SURVEYOR. THE CROWN SOLICITOR. ELECTIVE TRUSTEES: 0. G. VICKER Y, B.E., M.I.E. (Aust.). FRANK W. HILL. PROF. A. P. ELKIN, M.A., Ph.D. G. A. JOHNSO N. F. McDOWELL. PROF. J . R. A. McMILLAN, M.S., D .Sc.Agr. R. J. NOBLE, C.B.E., B.Sc.Agr., M.Sc., Ph.D. E. A. 1. HYDE. 1!. J. KENNY. M.Aust.l.M.M. PROF. R. L. CROCKER, D.Sc. F. L. S. -

Attachment A

Attachment A Report Prepared by External Planning Consultant 3 Recommendation It is resolved that consent be granted to Development Application D/2017/1652, subject to the following: (A) the variation sought to Clause 6.19 Overshadowing of certain public places in accordance with Clause 4.6 'Exceptions to development standards' of the Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 be supported in this instance; and (B) the requirement under Clause 6.21 of the Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 requiring a competitive design process be waived in this instance; and (C) the requirement under Clause 7.20 of the Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 requiring the preparation of a development control plan be waived in this instance; Reasons for Recommendation The reasons for the recommendation are as follows: (A) The proposal, subject to recommended conditions, is consistent with the objectives of the planning controls for the site and is compatible with the character of the area into which it will be inserted. It will provide a new unique element in the public domain which has been specifically designed to highlight Sydney’s main boulevard and the important civic precinct of Town Hall and the Queen Victoria Building. (B) The proposed artwork is permissible on the subject land and complies with all relevant planning controls with the exception of overshadowing of Sydney Town Hall steps. While the proposal will result in some additional shadowing of the steps this impact will be minor and is outweighed by the positive impacts of the proposal. (C) The proposal is of a nature compatible with the overall function of the locality as a civic precinct in the heart of the Sydney CBD. -

The Architecture of Scientific Sydney

Journal and Proceedings of The Royal Society of New South Wales Volume 118 Parts 3 and 4 [Issued March, 1986] pp.181-193 Return to CONTENTS The Architecture of Scientific Sydney Joan Kerr [Paper given at the “Scientific Sydney” Seminar on 18 May, 1985, at History House, Macquarie St., Sydney.] A special building for pure science in Sydney certainly preceded any building for the arts – or even for religious worship – if we allow that Lieutenant William Dawes‟ observatory erected in 1788, a special building and that its purpose was pure science.[1] As might be expected, being erected in the first year of European settlement it was not a particularly impressive edifice. It was made of wood and canvas and consisted of an octagonal quadrant room with a white conical canvas revolving roof nailed to poles containing a shutter for Dawes‟ telescope. The adjacent wooden building, which served as accommodation for Dawes when he stayed there overnight to make evening observations, was used to store the rest of the instruments. It also had a shutter in the roof. A tent-observatory was a common portable building for eighteenth century scientific travellers; indeed, the English portable observatory Dawes was known to have used at Rio on the First Fleet voyage that brought him to Sydney was probably cannibalised for this primitive pioneer structure. The location of Dawes‟ observatory on the firm rock bed at the northern end of Sydney Cove was more impressive. It is now called Dawes Point after our pioneer scientist, but Dawes himself more properly called it „Point Maskelyne‟, after the Astronomer Royal. -

EC English, Sydney

#Embassy Sydney January ACTIVITY CALENDAR Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 01 Jan 02 Jan 03 Jan 04 Jan 05 Jan 06 Jan 07 Jan Conversation Club Stop by the iconic Walk across the Harbour Four Thousand Fish at Fun Day Sunday:$2.60 Orientation for new Every Wednesday BBQ @ Bronte Beach Barangaroo Reserve Katharina Grosse @ students Pre int & below 10 am – 11am Bridge~ Its free $7.00 Carriageworks, Eveleigh th th QVB Int & above 1:45pm - 2:45pm Ends on 28 Jan 2018 Exhibition ends on 08 April 2018 08 Jan 09 Jan 10 Jan 11 Jan 12 Jan 13 Jan 14 Jan Sydney Festival Circus City At Parramatta Harbour Bridge Pylon Opera In the Domain @ Fun Day Sunday:$2.60 Orientation for new Village Sideshow Take a picnic at the Royal @ Prince Alfred Square $ 10.00 The Domain Sydney Visit Camp Cove@ students @ Hyde Park Botanic Gardens st Ends on 28th Jan 2018 Ends on 21 Jan 2018 (Does not include transport fee) 8PM Watson Bay 15 Jan 16 Jan 17 Jan 18 Jan 19 Jan 20 Jan 21 Jan Have a swim at the Fun Day Sunday:$2.60 Symphony Under the Orientation for new Glitterbox@Meriton Jurassic Plastic Taronga Zoo Sydney Saltwater pool @ Bondi Stars @ Parramatta Park Festival Village Hyde Park Icebergs Club @Sydney Town Hall @ $ 28.00 The Rocks Market students th th Ends 28 Jan 2018 Ends 28 Jan 2018 (Does not include transport fee) 8PM 10 am – 5pm $ 6.50 casual Entry 22 Jan 23 Jan 24 Jan 25 Jan 26 Jan 27 Jan 28 Jan Art: Warm Ties @ Embassy Fun day ~ Carriageworks Fun Day Sunday :$2.60 Orientation for new Vist Wendy's Secret Australia day~ NO Wear Something -

Scheherazade 11 – 13 Mar Sydney Town Hall THU 7 MAY & FRI 8 MAY / SYDNEY TOWN HALL SAT 9 MAY / SYDNEY COLISEUM THEATRE on SALE NOW

Scheherazade 11 – 13 Mar Sydney Town Hall THU 7 MAY & FRI 8 MAY / SYDNEY TOWN HALL SAT 9 MAY / SYDNEY COLISEUM THEATRE ON SALE NOW SYDNEYSYMPHONY.COM 2020 CONCERT SEASON SYMPHONY HOUR WEDNESDAY 11 MARCH, 7PM THURSDAY 12 MARCH, 7PM TEA AND SYMPHONY FRIDAY 13 MARCH, 11AM SYDNEY TOWN HALL Estimated durations: 10 minutes, Scheherazade 42 minutes Hypnotic and Sublime The concert will conclude at approximately 8pm (Wednesday and Thursday) and 12 noon (Friday). Alexander Shelley conductor n n n n n n n n Cover image: Alexander Shelley CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862–1918) Photo by: Thomas Dagg Prélude à ‘L’aprés-midi d’un faune’ NIKOLAI RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (1844–1908) Scheherazade – Symphonic Suite, Op.35 Largo e maestoso – Lento – Allegro non troppo (The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship) Lento (The Story of the Kalendar Prince) Andantino quasi allegretto (The Young Prince and the Young Princess) Allegro molto – Vivo – Allegro non troppo e maestoso – Lento (Festival at Baghdad – The Sea – The Ship Goes to Pieces on a Rock Surmounted by a Bronze Warrior – Conclusion) PRESENTING PARTNER THE ARTISTS Alexander Shelley conductor Born in London in October 1979, Alexander Shelley, the son of celebrated concert pianists, studied cello and conducting in Germany and first gained widespread attention when he was unanimously awarded first prize at the 2005 Leeds Conductors’ Competition, with the press describing him as “the most exciting and gifted young © GRANGER / BRIDGEMAN IMAGESGRANGER / © conductor to have taken this highly prestigious award”. In September 2015 he succeeded Pinchas Zukerman as Music Director of Canada’s National Arts Centre Orchestra. The ensemble has since been praised as “an orchestra transformed … hungry, bold, and unleashed” (Ottawa Citizen). -

CAMP Schedule

CAMP Schedule Monday June 1 – CAMP UP! The Summit will kick off with a climb up the iconic Sydney Harbour Bridge, and CAMPers will take part in the Town Hall opening event joined by some of leading thinkers, scientists and entrepreneurs from both countries, and pitch their idea in 1 minute to their fellow CAMPers, set expectations, bond with their team, feel part of something big and get ready for the transformative actions. 6:25am – 10:00am Sydney Harbour Bridge Climb Breakfast 10:45am – 12:30pm CAMP Summit Opening – Leading Innovation in the Asian Century – Sydney Town Hall Keynotes: Andrea Myles, CEO, CAMP Jack Zhang, Founder, Geek Park Moderator: Holly Ransom, Global Strategist Speakers: Jean Dong, Founder and Managing Director Spark Corporation Rick Chen, Co-founder, Pozible Andy Whitford, General Manager and Head of Greater China, Westpac Afternoon sessions – NSW Trade and Investment 1:00pm – 2:00pm Lunch 2:00pm – 2:30pm Mapping the CAMP Summit Experience: The Week Ahead 2:30pm – 3:30pm Pitch sessions 3:30pm – 4:30pm Team meeting & afternoon tea 4:30pm – 6:00pm Testing value and customer propositions 6:30pm – 8:30pm CAMP Welcome Reception: Sydney Tower Wednesday June 3 – Driving Change CAMPers will gain awareness on the challenges working between Australia and China. CAMPers will hear from inspiring entrepreneurs Tuesday June 2 – Navigating The Future on how one has to adjust to the different environments and markets. During the 3-hour-long PeerCAMP unConference, we will provide CAMPers and our learning partners with thirty-minute timeslots to create their own sessions and learn a wide range of nuts and bolts Leading innovation and change in the world requires navigating ambiguity, testing and validating the ideas with people to learn. -

Choral Itinerary

SAMPLE ITINERARY AUSTRALIAN INTERNATIONAL MUSIC FESTIVAL – Choral Ensembles June / July (subject to change) DAY ONE: June / July – SYDNEY (D) Morning Arrive into Sydney! Warm-natured, sun-kissed, and naturally good looking, Sydney is rather like its lucky, lucky residents. Situated on one of the world's most striking harbors, where the twin icons of the Sydney Opera House and Harbour Bridge steal the limelight, the relaxed Australian city is surprisingly close to nature. Within minutes you can be riding the waves on Bondi Beach, bushwalking in Manly, or gazing out across Botany Bay, where the first salt-encrusted Europeans arrived in the 18th century. Collect your luggage and move through customs and immigration. Meet your local Australian Tour Manager and load the coach. Depart on a Sydney Orientation Tour including stops in the Central Business District, Eastern Suburbs and Bondi Beach. Afternoon Lunch on own at Bondi Beach. Mid-afternoon, transfer and check in to a 3-star hotel, youth hostel or budget hotel in Sydney. Evening Dinner as a group in Sydney and possibly attend this evening’s Festival Concert. DAY TWO: June / July – SYDNEY (B) – Workshop Morning Breakfast as a group. This morning, transfer to a venue in Sydney (TBC – possibly Angel Place City Recital Hall or Sydney Conservatorium or similar). Enjoy a 1-hour workshop with a member of the Festival Faculty. Afternoon Lunch on your own in Sydney and enjoy a visit to Sydney Tower for magnificent views across Greater Sydney. Construction of Sydney Tower Centrepoint shopping centre began in the late 1970's with the first 52 shops opening in 1972. -

George Street 2020 – a Public Domain Activation Strategy

Sydney2030/Green/Global/Connected George Street 2020 A Public Domain Activation Strategy Adopted 10 August 2015 George Street 2020 A Public Domain Activation Strategy 01/ Revitalising George Street 1 Our vision for George Street The Concept Design Policy Framework Related City strategies George Street past and present 02/ The George Street Public Domain 11 Activation principles Organising principles Fixed elements Temporary elements 03/ Building use 35 Fine grain Public rest rooms and storage 04/ Building Elements 45 Signs Awnings Building materials and finish quality 05/ Public domain activation plans 51 06/ Ground floor frontage analysis 57 George Street 2020 - A Public Domain Activation Strategy Revitalising George Street 1.1 Our vision for George Street Building uses, particularly those associated with the street level, help activate the street by including public amenities By 2020 George Street will be transformed into and a fine grain, diverse offering of goods, services and Sydney’s new civic spine as part of the CBD light rail attractions. project. It will be a high quality pedestrian boulevard, linking Sydney’s future squares and key public Building elements including awnings, signage and spaces. materiality contribute to the pedestrian experience of George Street. This transformation is a unique opportunity for the City to maximise people’s enjoyment of the street, add vibrancy This strategy identifies principles and opportunities relating to the area and support retail and the local economy. This to these elements, and makes recommendations for the strategy plans for elements in the public domain as well design of George Street as well as policy and projects to as building edges and building uses to contribute to the contribute to the ongoing use and experience of the street. -

Anzac Memorial Considered for State Heritage Listing

3 March, 2010 ANZAC MEMORIAL CONSIDERED FOR STATE HERITAGE LISTING The ANZAC Memorial in Sydney’s Hyde Park is to be considered for listing on the State Heritage Register. Minister for Planning, Tony Kelly, said since its completion in 1934, the iconic building had been an important place of commemoration, especially on ANZAC Day. “As well as being a monument to the sacrifices of Australian servicemen and women, the ANZAC Memorial building has long been considered one of Australia’s greatest works of public art,” the Minister said. “The result of a creative collaboration between architect Bruce Dellit and sculptor Rayner Hoff, the ANZAC Memorial is arguably the finest expression of Art Deco monumentality in Australia. “It’s also closely linked to the landing of Australian troops at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, with fundraising for the memorial established on the first anniversary of the landing.” The building is associated with returned servicemen and women and their various organisations, including the RSL, which lobbied for the erection of the monument and occupied offices within it. Mr Kelly said the memorial represents NSW’s contribution to the group of national war memorials developed by each State capital during the inter-war period. “As a result, its heritage importance has a number of different dimensions including historical, aesthetic and social significance, and should it be considered for the State’s highest form of heritage protection,” the Minister said. The proposed listing, which follows the Government’s recent listing of three other iconic Sydney buildings – the Sydney Town Hall, the Queen Victoria Building and Luna Park – will be exhibited for public comment until Monday, March 22. -

Sydney Symphony Fellowship

2020 IMPACT REPORT “ The concert marked the SSO’s return to its former home... the Sydney Town Hall is an attractive venue: easy to get to, grandly ornate, and nostalgic for those who remember the SSO’s concerts there in earlier years. The Victorian-era interior was spectacular... and it had a pleasing “big hall” acoustic that will lend grandeur and spaciousness to the SSO’s concerts of orchestral masterworks.” The Australian, 2020 2 Ben Folds, The Symphonic Tour, in Sydney Town Hall (March 2020). Photo: Christie Brewster 3 2020: A TRUE ENSEMBLE PERFORMANCE On 13 March 2020, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra was silenced for the first time in its 89-year history by the global COVID-19 pandemic. Andrew Haveron performing Tim Stevenson’s 4 Elegies as part of the Sydney Symphony at Home series. Filmed by Jay Patel The year had started boldly, with the Orchestra With a forward path identified, the Orchestra In August, Chief Conductor Designate Simone opening its 2020 Season in Sydney Town Hall quickly pivoted to digital concert production Young braved international travel restrictions as its temporary home for two years while the and expanded its website into an online concert and a two-week hotel quarantine to travel to Sydney Opera House Concert Hall was renovated. gallery. Starting in April, the Orchestra delivered Sydney and lead the musicians in their first Thirty-four season performances had already 29 Sydney Symphony at Home performances, full-group musical activities since lockdown. taken place by the time COVID-19 emerged. four Cuatro performances with the Sydney Dance There were tears of joy and relief as instruments However, that morning’s sold-out performance of Company, 18 Chamber Sounds performances were raised under her baton for rehearsals Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade would turn out recorded live at City Recital Hall with a focus and recordings at City Recital Hall and in to be the Orchestra’s final performance for 2020. -

Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 Under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979

2012 No 628 New South Wales Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 I, the Minister for Planning and Infrastructure, pursuant to section 33A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979, adopt the mandatory provisions of the Standard Instrument (Local Environmental Plans) Order 2006 and prescribe matters required or permitted by that Order so as to make a local environmental plan as follows. (S07/01049) SAM HADDAD As delegate for the Minister for Planning and Infrastructure Published LW 14 December 2012 Page 1 2012 No 628 Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 Contents Page Part 1 Preliminary 1.1 Name of Plan 6 1.1AA Commencement 6 1.2 Aims of Plan 6 1.3 Land to which Plan applies 7 1.4 Definitions 7 1.5 Notes 7 1.6 Consent authority 7 1.7 Maps 7 1.8 Repeal of planning instruments applying to land 8 1.8A Savings provision relating to development applications 8 1.9 Application of SEPPs 9 1.9A Suspension of covenants, agreements and instruments 9 Part 2 Permitted or prohibited development 2.1 Land use zones 11 2.2 Zoning of land to which Plan applies 11 2.3 Zone objectives and Land Use Table 11 2.4 Unzoned land 12 2.5 Additional permitted uses for particular land 13 2.6 Subdivision—consent requirements 13 2.7 Demolition requires development consent 13 2.8 Temporary use of land 13 Land Use Table 14 Part 3 Exempt and complying development 3.1 Exempt development 27 3.2 Complying development 28 3.3 Environmentally sensitive areas excluded 29 Part 4 Principal development standards -

The Decline and Revival of Music Education in New South Wales Schools from 1920 to 1956

australiaa n societ s y fo r mumsic education e The decline and revival of music i ncorporated education in New South Wales schools, 1920-1956 Marilyn Chaseling School of Education, Southern Cross University, NSW. Email: [email protected] William E. Boyd School of Science, Environment & Engineering, Southern Cross University, NSW. Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper overviews the decline and revival of music education in New South Wales schools from 1920 to 1956. Commencing with a focus on vocal music during the period up to 1932, a time of decline in music teaching, the paper examines initiatives introduced in 1933 to address shortcomings in music education, and the subsequent changes in curriculum and teaching during the 1930s. Evidence of a variable revival lies in the school choral music movement of 1939 to 1956, and in how music education diversified beyond its vocal heritage from the late 1930s and early 1940s, with new emphasis on music appreciation, percussion, flutes, and recorders. By the mid 1950s, involvement in, and quality of, school instrumental music was continuously improving. Key words: school choral music, school choirs, Theodore Tearne, Herbert Treharne, Barbara Mettan, Victor McMahon, flute bands, percussion bands, inspectors of schools Australian Journal of Music Education 2014:2,46-61 Introduction children could be assembled, at short notice, to form choirs to perform at celebratory or This paper explores music in New South Wales commemorative events:4 a choir of over 5,000 (NSW) state primary schooling from 1920 to children performed in 1897 for the Jubilee 1956, through the lens of music teaching and Celebrations of Queen Victoria, and the hand- 1 practice, building on the research of Dugdale picked choir of three thousand sang at the Public 2 and of Stevens into music in NSW state primary School’s Patriotic Display in 1900;5 a colossal choir schools prior to 1920.