Undecomposed Twigs in the Leaf Litter As Nest-Building Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Determinants of Leaf Litter Ant Community Composition

Environmental determinants of leaf litter ant community composition along an elevational gradient Mélanie Fichaux, Jason Vleminckx, Elodie Alice Courtois, Jacques Delabie, Jordan Galli, Shengli Tao, Nicolas Labrière, Jérôme Chave, Christopher Baraloto, Jérôme Orivel To cite this version: Mélanie Fichaux, Jason Vleminckx, Elodie Alice Courtois, Jacques Delabie, Jordan Galli, et al.. Environmental determinants of leaf litter ant community composition along an elevational gradient. Biotropica, Wiley, 2020, 10.1111/btp.12849. hal-03001673 HAL Id: hal-03001673 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03001673 Submitted on 12 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. BIOTROPICA Environmental determinants of leaf-litter ant community composition along an elevational gradient ForJournal: PeerBiotropica Review Only Manuscript ID BITR-19-276.R2 Manuscript Type: Original Article Date Submitted by the 20-May-2020 Author: Complete List of Authors: Fichaux, Mélanie; CNRS, UMR Ecologie des Forêts de Guyane (EcoFoG), AgroParisTech, CIRAD, INRA, Université -

Download PDF File

ISSN 1994-4136 (print) ISSN 1997-3500 (online) Myrmecological News Volume 25 October 2017 Schriftleitung / editors Florian M. STEINER, Herbert ZETTEL & Birgit C. SCHLICK-STEINER Fachredakteure / subject editors Jens DAUBER, Falko P. DRIJFHOUT, Evan ECONOMO, Heike FELDHAAR, Nicholas J. GOTELLI, Heikki O. HELANTERÄ, Daniel J.C. KRONAUER, John S. LAPOLLA, Philip J. LESTER, Timothy A. LINKSVAYER, Alexander S. MIKHEYEV, Ivette PERFECTO, Christian RABELING, Bernhard RONACHER, Helge SCHLÜNS, Chris R. SMITH, Andrew V. SUAREZ Wissenschaftliche Beratung / editorial advisory board Barry BOLTON, Jacobus J. BOOMSMA, Alfred BUSCHINGER, Daniel CHERIX, Jacques H.C. DELABIE, Katsuyuki EGUCHI, Xavier ESPADALER, Bert HÖLLDOBLER, Ajay NARENDRA, Zhanna REZNIKOVA, Michael J. SAMWAYS, Bernhard SEIFERT, Philip S. WARD Eigentümer, Herausgeber, Verleger / publisher © 2017 Österreichische Gesellschaft für Entomofaunistik c/o Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Burgring 7, 1010 Wien, Österreich (Austria) Myrmecological News 25 67-81 Vienna, October 2017 Crematogaster abstinens and Crematogaster pygmaea (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae): from monogyny and monodomy to polygyny and polydomy Glauco Bezerra MARTINS SEGUNDO , Jean-Christophe DE BISEAU , Rodrigo Machado FEITOSA , José Evaldo Vasconcelos CARLOS , Lucas Rocha SÁ, Matheus Torres Marinho Bezerril FONTENELLE & Yves QUINET Abstract Polygyny and polydomy are key features in the nesting biology of many ants, raising important questions in social insect biology, in particular about the ecological determinants of -

Evolutionary Dynamics of Shared Niche Construction

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/002378; this version posted February 5, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Evolutionary dynamics of shared niche construction Philip Gerlee∗ and Alexander R.A. Anderson Integrated Mathematical Oncology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute 12902 Magnolia Drive Tampa, FL 33612 (Dated: January 31, 2014) Many species engage in niche construction that ultimately leads to an increase in the carrying capacity of the population. We have investigated how the specificity of this behaviour affects evo- lutionary dynamics using a set of coupled logistic equations, where the carrying capacity of each genotype consists of two components: an intrinsic part and a contribution from all genotypes present in the population. The relative contribution of the two components is controlled by a specificity parameter γ, and we show that the ability of a mutant to invade a resident population depends strongly on this parameter. When the carrying capacity is intrinsic, selection is almost exclusively for mutants with higher carrying capacity, while a shared carrying capacity yields selection purely on growth rate. This result has important implications for our understanding of niche construction, in particular the evolutionary dynamics of tumor growth. In models of density-dependent growth the carrying ca- harder for other genotypes to exploit it, whereas a more pacity plays a pivotal role [1]. It represents the maximal general modification is easier to free-ride on. -

Tropical Ecology of the Amazon SFS 3830

Tropical Ecology of the Amazon SFS 3830 Laura Morales, Ph.D. Resident Lecturer The School for Field Studies (SFS) Center for Amazon Studies (CAS) Iquitos, Peru This syllabus may develop or change over time based on local conditions, learning opportunities, and faculty expertise. Course content may vary from semester to semester. www.fieldstudies.org © 2018 The School for Field Studies F18 Course Overview Tropical regions are highly biodiverse and the Western Amazon region is one of THE MOST biodiverse places in the tropics. Ecology, the study of interactions of organisms with their environment, both its living and non-living components, can help us understand why and how this region harbors such a variety of life. In Tropical Ecology of the Amazon, we will be looking at the natural history and processes that created and sustain the region’s biodiversity at multiple scales: species, community, ecosystem, and landscape. The main goal of this course is for students to understand the processes that contribute to the diversity of life in the Western Amazon and gain insight into similar processes operating in tropical areas around the world. We will explore fundamental principles of ecology by studying a diverse set of ecosystems, habitats and species found here, including a variety of lowland tropical forest types and high-elevation forests at the headwaters of the Amazon River in the Andes Mountains. Our exploration is grounded by three themes: 1. What is biodiversity? evolutionary origins, scales, and measurement 2. Why are the tropics so diverse? Interactions, ecosystem dynamics, succession 3. How does biodiversity respond to global change? Climate and land-use (past, present, future) Using field methodology and guided by the scientific method, we will focus on learning tools that will allow students to measure, describe, and explain biodiversity and its dynamics. -

Sociobiology 61(2): 119-132 (June, 2014) DOI: 10.13102/Sociobiology.V61i2.119-132

Sociobiology 61(2): 119-132 (June, 2014) DOI: 10.13102/sociobiology.v61i2.119-132 Sociobiology An international journal on social insects Research article - ANTS Ant Communities along a Gradient of Plant Succession in Mexican Tropical Coastal Dunes P Rojas1, C Fragoso1, WP Mackay2 1 - Instituto de Ecología A.C. (INECOL). Xalapa, México. 2 - University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, USA. Article History Abstract Edited by Most of Mexican coastal dunes from the Gulf of Mexico have been severely disturbed by Kleber Del-Claro, UFU, Brazil human activities. In the state of Veracruz, the La Mancha Reserve is a very well preserved Received 12 March 2014 Initial acceptance 09 April 2014 coastal community of sand dunes, where plant successional gradients are determined Final acceptance 12 May 2014 by topography. In this study we assessed species richness, diversity and faunal composi- tion of ant assemblages in four plant physiognomies along a gradient of plant succes- Keywords sion: grassland, shrub, deciduous forest and subdeciduous forest. Using standardized Ant assemblages, species richness, and non-standardized sampling methods we found a total of 121 ant species distributed diversity, La Mancha, México in 41 genera and seven subfamilies. Grassland was the poorest site (21 species) and Corresponding author subdeciduous forest the richest (102 species). Seven species, with records in ≥10% of Patricia Rojas samples, accounted 40.8% of total species occurrences: Solenopsis molesta (21.6%), S. Instituto de Ecología A.C. (INECOL) geminata (19.5%), Azteca velox (14%), Brachymyrmex sp. 1LM (11.7%), Dorymyrmex Carretera Antigua a Coatepec 351 bicolor (11.2%), Camponotus planatus (11%) and Pheidole susannae (10.7%). -

Trabalhos Práticos De Ecologia Comportamental

Trabalhos Práticos da disciplina de Ecologia Comportamental Turmas de Licenciatura e Bacharelado da Graduação em Ciências Biológicas (010464 A e B) Departamento de Hidrobiologia (DHb) Universidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar) -2018- Vídeos dos experimentos disponíveis no Canal do YouTube Divulgando Ciência DHb - UFSCar: https://goo.gl/cvkGfm Professores responsáveis pela disciplina: Prof. Hugo Sarmento Prof. Rhainer Guillermo Ferreira LISTA DE TRABALHOS MOSCAS ANASTREPHA FRATERCULUS DEMONSTRAM PREFERÊNCIA CROMÁTICA NO FORRAGEIO Henrique Santarosa, Natalia Bueno, Renan C. S. Pereira CAPACIDADE DE RECONHECIMENTO DE PRESA PELO PREDADOR RHINELLA ORNATA (ANURA, BUFONIDAE) DIANTE DE DOIS TIPOS DIFERENTES DE BACKGROUND Affonso Orlandi Neto, Leonardo G. da Rocha, Letícia Keller B. C. Lopes O NÚMERO DE NINHOS EM COLÔNIA POLIDÔMICA AFETA TAXA DE RECRUTAMENTO EM CEPHALOTES AFF. DEPRESSUS (KLUG, 1824) (FORMICIDAE:MYRMICINAE). Gabriela C. Mendes, Leonardo S. Ricioli, Marianela Pini AVALIAÇÃO DO EFEITO DA LUMINOSIDADE NO INVESTIMENTO DE FORRAGEAMENTO EM LARVAS DE NEUROPTERA: MYRMELEONTIDAE Beatriz Segnini Soares, Márcia Cristina Martins da Silva, Maria Aparecida Gomes da Silva MICROCRUSTÁCEO CERIODAPHNIA SILVESTRII DEMONSTRA PREFERÊNCIA ALIMENTAR POR ANKISTRODESMUS DENSUS D EVIDO A MORFOLOGIA DE SUA PAREDE CELULAR Ana Beatriz Janduzzo, Gustavo Alexandre Cruz & Heloisa Bertolli de Almeida INFLUÊNCIA DO TAMANHO DA PRESA NA CONSTRUÇÃO DE ARMADILHAS POR LARVAS DE FORMIGA-LEÃO EM DIFERENTES SUBSTRATOS Anelyse Cortez, Solange Antão, Valentine Spagnol USO -

SANDERS-DISSERTATION-2015.Pdf (13.52Mb)

Disentangling the Coevolutionary Histories of Animal Gut Microbiomes The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Sanders, Jon G. 2015. Disentangling the Coevolutionary Histories of Animal Gut Microbiomes. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463127 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Disentangling the coevolutionary histories of animal gut microbiomes A dissertation presented by Jon Gregory Sanders to Te Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology in partial fulfllment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April, 2015 ㏄ 2015 – Jon G. Sanders Tis work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Professor Naomi E. Pierce Jon G. Sanders Professor Peter R. Girguis Disentangling the coevolutionary histories of animal gut microbiomes ABSTRACT Animals associate with microbes in complex interactions with profound ftness consequences. Tese interactions play an enormous role in the evolution of both partners, and recent advances in sequencing technology have allowed for unprecedented insight into the diversity and distribution of these associations. -

Denisse Dalgo Andrade

SAN FRANCISCO DE QUITO UNIVERSITY Effects Of The Presence Of Myrmelachista Schumanni Ants On The Abundance And Diversity Of Edaphic Macro Invertebrates Within ‘Devil’s Gardens’. Denisse Dalgo Andrade Degree Thesis Requirement For Obtaining The Degree In Applied Ecology College of Biological and Environmental Sciences Quito, Ecuador Agosto 2012 Email: [email protected] ii SAN FRANCISCO DE QUITO UNIVERSITY College of Biological and Environmental Sciences APPROVAL OF THESIS Effects Of The Presence Of Myrmelachista Schumanni Ants On The Abundance And Diversity Of Edaphic Macro Invertebrates Within „Devil‟s Gardens‟. Denisse Dalgo Andrade David Romo, Ph.D. Thesis Director ……………………………………………………… Stella de la Torre, Ph. D. Dean of College of Biological and Environmental Sciences ……………………………………………………… Quito, August 2012 iii AUTHOR COPYRIGHTS © Author Copyrights Denisse Dalgo Andrade 2012 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank the Tiputini Biodiversity Station staff both in Quito and Tiputini; David Romo, my Thesis Director; Stella de la Torre, Dean of College of Biological and Environmental Sciences; Carlos Valle and Diego Cisneros for their guidance and constructive reviews that improved the thesis and the staff of the Aquatic Ecology Laboratory for facilitating the use of their equipment and laboratory. I would like to thank also to the Scholarship Committee of the USFQ, to my partners and my mother. v ABSTRACT „Devil‟s gardens‟ are created by Myrmelachista schumanni ants, which nest in the hollow, swollen stems of Duroia hirsuta, and create these areas devoid of vegetation by poisoning all plants, with the exception their host plants, with formic acid. In this study I investigated if in addition to killing encroaching vegetation around their host plants, M. -

V. 15 N. 1 Janeiro/Abril De 2020

v. 15 n. 1 janeiro/abril de 2020 Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi Ciências Naturais v. 15, n. 1 janeiro-abril 2020 BOLETIM DO MUSEU PARAENSE EMÍLIO GOELDI. CIÊNCIAS NATURAIS (ISSN 2317-6237) O Boletim do Museu Paraense de História Natural e Ethnographia foi criado por Emílio Goeldi e o primeiro fascículo surgiu em 1894. O atual Boletim é sucedâneo daquele. IMAGEM DA CAPA Elaborada por Rony Peterson The Boletim do Museu Paraense de História Natural e Ethnographia was created by Santos Almeida e Lívia Pires Emilio Goeldi, and the first number was issued in 1894. The present one is the do Prado. successor to this publication. EDITOR CIENTÍFICO Fernando da Silva Carvalho Filho EDITORES DO NÚMERO ESPECIAL Lívia Pires do Prado Rony Peterson Santos Almeida EDITORES ASSOCIADOS Adriano Oliveira Maciel Alexandra Maria Ramos Bezerra Aluísio José Fernandes Júnior Débora Rodrigues de Souza Campana José Nazareno Araújo dos Santos Junior Valéria Juliete da Silva William Leslie Overal CONSELHO EDITORIAL CIENTÍFICO Ana Maria Giulietti - Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana - Feira de Santana - Brasil Augusto Shinya Abe - Universidade Estadual Paulista - Rio Claro - Brasil Carlos Afonso Nobre - Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais - São José dos Campos - Brasil Douglas C. Daly - New York Botanical Garden - New York - USA Hans ter Steege - Utrecht University - Utrecht - Netherlands Ima Célia Guimarães Vieira - Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi - Belém - Brasil John Bates - Field Museum of Natural History - Chicago - USA José Maria Cardoso da -

Mutualism (Biology)

Mutualism (biology) Measuring the exact fitness benefit to the individuals in a mutualistic relationship is not always straightfor- ward, particularly when the individuals can receive ben- efits from a variety of species, for example most plant- pollinator mutualisms. It is therefore common to cate- gorise mutualisms according to the closeness of the as- sociation, using terms such as obligate and facultative. Defining “closeness,” however, is also problematic. It can refer to mutual dependency (the species cannot live with- out one another) or the biological intimacy of the rela- tionship in relation to physical closeness (e.g., one species living within the tissues of the other species).[4] The term “mutualism” was introduced by Pierre-Joseph van Beneden in 1876.[5] 1 Types of relationships Hummingbird hawkmoth drinking from Dianthus. Pollination is a classic example of mutualism. Mutualistic transversals can be thought of as a form of “biological barter”[4] in mycorrhizal associations be- tween plant roots and fungi, with the plant provid- Mutualism is the way two organisms of different species ing carbohydrates to the fungus in return for primar- exist in a relationship in which each individual benefits ily phosphate but also nitrogenous compounds. Other from the activity of the other. Similar interactions within examples include rhizobia bacteria that fix nitrogen for a species are known as co-operation. Mutualism can be leguminous plants (family Fabaceae) in return for energy- contrasted with interspecific competition, in which each containing carbohydrates.[6] species experiences reduced fitness, and exploitation, or parasitism, in which one species benefits at the expense of the other. -

Army Ants Such As Eciton Burchellii

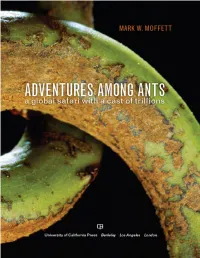

ADVENTURES AMONG ANTS The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the General Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Foundation. University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2010 by Mark W. Moffett Title page: A Bornean carpenter ant, Camponotus schmitzi, traveling along the spiral base of a pitcher plant. The ant fishes prey out of the liquid-filled pitcher of this carnivorous plant (see photograph on page 142). Ogden Nash’s “The Ant” © 1935 by Ogden Nash is reprinted with permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd. Design and composition: Jody Hanson Text: 9.5/14 Scala Display: Grotesque Condensed Indexing: Victoria Baker Printed through: Asia Pacific Offset, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moffett, Mark W. Adventures among ants : a global safari with a cast of trillions / Mark W. Moffett. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-520-26199-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Ants—Behavior. 2. Ant communities. 3. Ants—Ecology. I. Title. QL568.F7M64 2010 595.79'615—dc22 2009040610 Manufactured in China 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) This book celebrates a triumvirate of extraordinary human beings: Edward O. -

Synonymic List of Neotropical Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

BIOTA COLOMBIANA Special Issue: List of Neotropical Ants Número monográfico: Lista de las hormigas neotropicales Fernando Fernández Sebastián Sendoya Volumen 5 - Número 1 (monográfico), Junio de 2004 Instituto de Ciencias Naturales Biota Colombiana 5 (1) 3 -105, 2004 Synonymic list of Neotropical ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Fernando Fernández1 and Sebastián Sendoya2 1Profesor Asociado, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, AA 7495, Bogotá D.C, Colombia. [email protected] 2 Programa de Becas ABC, Sistema de Información en Biodiversidad y Proyecto Atlas de la Biodiversidad de Colombia, Instituto Alexander von Humboldt. [email protected] Key words: Formicidae, Ants, Taxa list, Neotropical Region, Synopsis Introduction Ant Phylogeny Ants are conspicuous and dominant all over the All ants belong to the family Formicidae, in the superfamily globe. Their diversity and abundance both peak in the tro- Vespoidea, within the order Hymenoptera. The most widely pical regions of the world and gradually decline towards accepted phylogentic schemes for the superfamily temperate latitudes. Nonetheless, certain species such as Vespoidea place the ants as a sister group to Vespidae + Formica can be locally abundant in some temperate Scoliidae (Brother & Carpenter 1993; Brothers 1999). countries. In the tropical and subtropical regions numerous Numerous studies have demonstrated the monophyletic species have been described, but many more remain to be nature of ants (Bolton 1994, 2003; Fernández 2003). Among discovered. Multiple studies have shown that ants represent the most widely accepted characters used to define ants as a high percentage of the biomass and individual count in a group are the presence of a metapleural gland in females canopy forests.