Reconstructive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recognizing When a Child's Injury Or Illness Is Caused by Abuse

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Recognizing When a Child’s Injury or Illness Is Caused by Abuse PORTABLE GUIDE TO INVESTIGATING CHILD ABUSE U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street NW. Washington, DC 20531 Eric H. Holder, Jr. Attorney General Karol V. Mason Assistant Attorney General Robert L. Listenbee Administrator Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Office of Justice Programs Innovation • Partnerships • Safer Neighborhoods www.ojp.usdoj.gov Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention www.ojjdp.gov The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Assistance; the Bureau of Justice Statistics; the National Institute of Justice; the Office for Victims of Crime; and the Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking. Recognizing When a Child’s Injury or Illness Is Caused by Abuse PORTABLE GUIDE TO INVESTIGATING CHILD ABUSE NCJ 243908 JULY 2014 Contents Could This Be Child Abuse? ..............................................................................................1 Caretaker Assessment ......................................................................................................2 Injury Assessment ............................................................................................................4 Ruling Out a Natural Phenomenon or Medical Conditions -

Nasolabial and Forehead Flap Reconstruction of Contiguous Alar

Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery (2017) 70, 330e335 Nasolabial and forehead flap reconstruction of contiguous alareupper lip defects Jonathan A. Zelken a,b, Sashank K. Reddy c, Chun-Shin Chang a, Shiow-Shuh Chuang a, Cheng-Jen Chang a, Hung-Chang Chen a, Yen-Chang Hsiao a,* a Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taipei, Taiwan b Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Breastlink Medical Group, Laguna Hills, CA, USA c Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA Received 4 May 2016; accepted 31 October 2016 KEYWORDS Summary Background: Defects of the nasal ala and upper lip aesthetic subunits can be Nasal reconstruction; challenging to reconstruct when they occur in isolation. When defects incorporate both Nasolabial flap; the subunits, the challenge is compounded as subunit boundaries also require reconstruc- Rhinoplasty; tion, and local soft tissue reservoirs alone may provide inadequate coverage. In such cases, Forehead flap we used nasolabial flaps for upper lip reconstructionandaforeheadflapforalarrecon- struction. Methods: Three men and three women aged 21e79 years (average, 55 years) were treated for defects of the nasal ala and upper lip that resulted from cancer (n Z 4) and trauma (n Z 2). Unaffected contralateral subunits dictated the flap design. The upper lip subunit was excised and replaced with a nasolabial flap. The flap, depending on the contralateral reference, determined accurate alar base position. A forehead flap resurfaced or replaced the nasal ala. Autologous cartilage was used in every case to fortify the forehead flap reconstruction. Results: Patients were followed for 25.6 months (range, 1e4 years). -

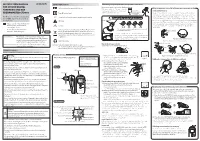

Instruction Manual for Citizen Digital Forehead And

INSTRUCTION MANUAL Symbol Explanations Measuring body temperature (temperature detection) Remove the probe cap and check the probe tip. FOR CITIZEN DIGITAL Refer to instruction manual before use. How to measure correctly in the ear measurement mode * When using it for the first time, open the FOREHEAD AND EAR battery cap and remove the insulation Open the Temperature basics battery cap to THERMOMETER CTD710 Type BF applied part sheet under the battery cap. remove the All objects radiate heat. This device consists of a probe with a built-in insulation sheet. infrared sensor that measures body temperature by detecting the heat Thank you very much for purchasing IP22 Classification for water ingress and particulate matter. radiated by the eardrum and surrounding tissue. Figure 4 shows the the CITIZEN digital forehead and ear Keeping the probe window clean tortuous anatomy of a normal ear canal. As shown in Figure 5, hold the thermometer. Warning Probe window ear and gently pull it back at an angle or pull it straight back to straighten out the ear canal. The shape of the ear canal differs from individual, check • Please read all of the information in before measurement. Accurate temperature measurements make it this instruction manual before Caution essential to straighten the ear canal so that the probe tip directly faces operating the device. the eardrum. • Be sure to have this instruction Indicates this device is subject to the Waste Electrical and Dirt in the probe window will impact the accuracy of temperature detection. External auditory manual to hand during use. 1902LA Electronic Equipment Directive in the European Union. -

Ear and Forehead Thermometer

Ear and Forehead Thermometer INSTRUCTION MANUAL Item No. 91807 19.PJN174-14_GA-USA_HHD-Ohrthermometer_DSO364_28.07.14 Montag, 28. Juli 2014 14:37:38 USAD TABLE OF CONTENTS No. Topic Page 1.0 Definition of symbols 5 2.0 Application and functionality 6 2.1 Intended use 6 2.2 Field of application 7 3.0 Safety instructions 7 3.1 General safety instructions 7 3.3 Environment for which the DSO 364 device is not suited 9 3.4 Usage by children and adolescents 10 3.5 Information on the application of the device 10 4.0 Questions concerning body temperature 13 4.1 What is body temperature? 13 4.2 Advantages of measuring the body tempera- ture in the ear 14 4.3 Information on measuring the body tempera- ture in the ear 15 5.0 Scope of delivery / contents 16 6.0 Designation of device parts 17 7.0 LCD display 18 8.0 Basic functions 19 8.1 Commissioning of the device 19 8.2 Warning indicator if the body temperature is 21 too high 2 19.PJN174-14_GA-USA_HHD-Ohrthermometer_DSO364_28.07.14 Montag, 28. Juli 2014 14:37:38 TABLE OF CONTENTS USA No. Topic Page 8.3 Backlighting / torch function 21 8.4 Energy saving mode 22 8.5 Setting °Celsius / °Fahrenheit 22 9.0 Display / setting time and date 23 9.1 Display of time and date 23 9.2 Setting time and date 23 10.0 Memory mode 26 11.0 Measuring the temperature in the ear 28 12.0 Measuring the temperature on the forehead 30 13.0 Object temperature measurement 32 14.0 Disposal of the device 33 15.0 Battery change and information concerning batteries 33 16.0 Cleaning and care 36 17.0 “Cleaning” warning indicator 37 18.0 Calibration 38 19.0 Malfunctions 39 20.0 Technical specification 41 21.0 Warranty 44 3 19.PJN174-14_GA-USA_HHD-Ohrthermometer_DSO364_28.07.14 Montag, 28. -

Core Strength Exercises

CORE STRENGTH EXERCISES • The main muscles involved with Core Strength include muscles of the abdomen, hip flexors and low back postural muscles. • It is important to maintain proper strength of these muscles to prevent and rehabilitate from low back / pelvic dysfunction and pain. • All of these exercises should be comfortable and not produce pain or discomfort. Bracing: The Key to preventing low back injuries Abdominal Bracing – Lying down • Lie down, face up with your knees bent and feet on floor. • Contract your stomach muscles so that you imagine pushing your low back to the floor or that you are pulling your belly button to your spine. Abdominal Bracing - Standing • Stand up straight and place one hand on the small of the back and one hand on your abdomen. • Bend Forward at the waist and feel the lower back muscles contract (extensors). • Come back up to neutral to relax the low back muscles. • You will feel the low back muscles contract when you contract your abdominal and gluteal muscles. Bracing technique and curling • Lay on the ground on your back. • One leg is bent and the other leg remains flat on the floor. Your hands can be on your chest or at your side. • Fix your eyes on a spot on the ceiling directly above you. • Tighten your stomach muscles. • Holding the stomach contraction, lift your shoulder blades and head off the floor while looking at that spot on the ceiling. Hold for 3-10 seconds and repeat three times. • Switch leg positions and repeat the technique. Beginner to Intermediate position • Position yourself on your hands and knees with your pelvis and thighs at 90 degrees and upper back and arms at 90 degrees. -

Facial Image Comparison Feature List for Morphological Analysis

Disclaimer: As a condition to the use of this document and the information contained herein, the Facial Identification Scientific Working Group (FISWG) requests notification by e-mail before or contemporaneously to the introduction of this document, or any portion thereof, as a marked exhibit offered for or moved into evidence in any judicial, administrative, legislative, or adjudicatory hearing or other proceeding (including discovery proceedings) in the United States or any foreign country. Such notification shall include: 1) the formal name of the proceeding, including docket number or similar identifier; 2) the name and location of the body conducting the hearing or proceeding; and 3) the name, mailing address (if available) and contact information of the party offering or moving the document into evidence. Subsequent to the use of this document in a formal proceeding, it is requested that FISWG be notified as to its use and the outcome of the proceeding. Notifications should be sent to: Redistribution Policy: FISWG grants permission for redistribution and use of all publicly posted documents created by FISWG, provided the following conditions are met: Redistributions of documents, or parts of documents, must retain the FISWG cover page containing the disclaimer. Neither the name of FISWG, nor the names of its contributors, may be used to endorse or promote products derived from its documents. Any reference or quote from a FISWG document must include the version number (or creation date) of the document and mention if the document is in a draft status. Version 2.0 2018.09.11 Facial Image Comparison Feature List for Morphological Analysis 1. -

Surgical Anatomy of the Ligamentous Attachments in the Temple and Periorbital Regions

Cosmetic Surgical Anatomy of the Ligamentous Attachments in the Temple and Periorbital Regions Christopher J. Moss, M.B., B.S., F.R.A.C.S., Dip.Anat., Bryan C. Mendelson, F.R.C.S.(E), F.R.A.C.S., F.A.C.S., and G. Ian Taylor, F.R.C.S., F.R.A.C.S., M.D. Melbourne, Australia This study documents the anatomy of the deep attach- complex system of deep attachments that arise ments of the superficial fasciae within the temporal and from the underlying deep fascia/periosteum. periorbital regions. A highly organized and consistent three-dimensional connective tissue framework supports The subSMAS plane that contains these attach- the overlying skin and soft tissues in these areas. ments is therefore not always a simple cleavage The regional nerves and vessels display constant and plane. This explains why surgical dissection is predictable relationships with both the fascial planes and considerably more complicated in the midfa- their ligamentous attachments. Knowledge of these rela- tionships allows the surgeon to use the tissue planes and cial, temporal, and periorbital regions than in soft-tissue ligaments as intraoperative landmarks for the the scalp. vital neurovascular structures. This results in improved In the cheek, these deep attachments have efficiency and safety for aesthetic procedures in these been defined as the zygomatic, masseteric, and regions. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 105: 1475, 2000.) mandibular-cutaneous ligaments.21,22 These lig- aments provide a lateral line of fixation for the mobile tissues of the medial cheek. Release of The patterns of arrangement of the layers of these retaining ligaments is fundamental to the superficial fascia in the cheek,1–9 forehead,10–13 14 15,16 extended SMAS technique of “deep-plane” sur- scalp, and temple have been well de- 18,19,23,24 scribed. -

Human Anatomy and Physiology

LECTURE NOTES For Nursing Students Human Anatomy and Physiology Nega Assefa Alemaya University Yosief Tsige Jimma University In collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education 2003 Funded under USAID Cooperative Agreement No. 663-A-00-00-0358-00. Produced in collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education. Important Guidelines for Printing and Photocopying Limited permission is granted free of charge to print or photocopy all pages of this publication for educational, not-for-profit use by health care workers, students or faculty. All copies must retain all author credits and copyright notices included in the original document. Under no circumstances is it permissible to sell or distribute on a commercial basis, or to claim authorship of, copies of material reproduced from this publication. ©2003 by Nega Assefa and Yosief Tsige All rights reserved. Except as expressly provided above, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the author or authors. This material is intended for educational use only by practicing health care workers or students and faculty in a health care field. Human Anatomy and Physiology Preface There is a shortage in Ethiopia of teaching / learning material in the area of anatomy and physicalogy for nurses. The Carter Center EPHTI appreciating the problem and promoted the development of this lecture note that could help both the teachers and students. -

Original Articles General Overgrowth Inthe Fragile X Syndrome

7646 Med Genet 1995;32:764-769 Original articles J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.32.10.764 on 1 October 1995. Downloaded from General overgrowth in the fragile X syndrome: variability in the phenotypic expression of the FMR1 gene mutation Bert B A de Vries, Hazel Robinson, Irene Stolte-Dijkstra, Cecil V Tjon Pian Gi, Piet F Dijkstra, Jaap van Doom, Dicky J J Halley, Ben A Oostra, Gillian Turner, Martinus F Niermeijer Department of Clinical Genetics, University Hospital Dijkzigt and Erasmus Abstract In addition, a Sotos-like phenotype was re- University, The fragile X syndrome, which often pre- ported in 1986 in two fragile X boys featuring Rotterdam, The Netherlands sents in childhood with overgrowth, may in large size at birth, unusual length, large head L B A de Vries some cases show some diagnostic overlap circumference, and minor facial anomalies.'5 D J J Halley with classical Sotos syndrome. We de- Here we report clinical, endocrine, and DNA B A Oostra M F Niermeijer scribe four fragile X patients with general studies in four fragile X patients with over- overgrowth, all ofwhom are from families growth. Fragile X Department, with other affected relatives who show the Prince of Wales Hospital, classic Martin-Bell phenotype. Molecular Randwick, studies of the FMR1 gene in all cases Patients and methods NSW, Australia showed the typical full mutation as seen in Four mentally retarded males with phenotypic H Robinson males affected by the fragile X syndrome. features resembling Sotos syndrome were iden- G Turner Endocrine studies were unremarkable, ex- tified as fragile X positive either by cytogenetic Department of cept in one case where there were raised analysis (cases 1, 3, and 4) or by gene mutation Medical Genetics, levels ofinsulin-like growth factor-I (IGF- analysis (case 2) and are the subjects of this University of Groningen, I) and insulin-like growth factor binding report. -

Exergen Temporalscanner

BulletPointsofImportanceinanInserviceforUsingtheExergenTemporalScannerThermometer x Basics: BeginwithbasicssonursingstaffcanseehowtheTemporalScannershouldbeused,butfirstuse yourforefingerratherthantheinstrument: 1. Placeyourforefingerinthecenterofyourforehead. 2. Slideitinastraightlineovertoyourhairline. 3. Liftyourforefingerandtouchthatlittlesoftdepressionyourneckjustbelowyourearlobe. IfyouhadtheExergenTemporalArteryThermometerinyourhand,youwouldhavejusttakenthe fastest,gentlest,mostaccuratetemperatureintheworld! x BasicStepsinUsingtheTemporalScanner: x Scaninastraightlineandyouwillnevermisstheartery–here’swhy: 1. Weallknowthatthetemporalarterycomesupthesideofthefacefromtheexternal carotids,but,itcangodeep,introducingavariableunsuitabletomakinganaccurate measurement. 2. Thesuperficialpartofthetemporalarteryisourtarget.Thisislocatedupintheforehead, about2mmbelowtheskin,literallytrappedbetweentheskinandtheskull. 3. Whileweknowhowdeepthesuperficialpartofthearteryis,itsexactlocationvarieswith eachindividual,whichiswhywescanallowingtheTATtolocateit,somethinglikearadar detector. x Thetouchbehindtheearistoassurethecorrectreadingifthepatientissweaty–here’swhy: 1. Iftheforeheadismoist,theeffectofevaporativecoolingwillresultinalowreading, however, 2. Sincevasodilationis100%assuredwhensweating,andwesweatlastontheneck,unless thepatientiscompletelysweaty,thetouchontheneckjustbehindtheearlobewilloverride theeffectofevaporativecooling. 3. Ifthepatientiscompletelysweaty,eitherreturninabout10minutestotakethetemp,or placeanExergenfilmstripoverthetemporalarteryareaandscanoverthefilm. -

Lidocaine Cream in Primary Premature Ejaculation

International Journal of Impotence Research (2014) 26, 186–190 & 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0955-9930/14 www.nature.com/ijir ORIGINAL ARTICLE A reassessment of penile sensory pathways and effects of prilocaine–lidocaine cream in primary premature ejaculation J-D Xia1, L-H Zhou2, Y-F Han1, Y Chen1,2, R Wang3 and Y-T Dai1,2 To assess the penile sensory pathway abnormalities of the patients with primary premature ejaculation (PPE) and effects of prilocaine–lidocaine (PLA) cream, we enrolled 82 PPE patients and 34 normal potent male volunteers. Somatosensory evoked potentials of dorsal nerve (DNSEP) and glans penis (GPSEP) were performed in each subject. In addition, among the 82 patients, 60 were selected and randomly divided into PLA and placebo subgroups, each with 30 patients. Cream was applied evenly on the glans penis for 10 min and washed off just before DNSEP and GPSEP were repeatedly measured. Mean latencies of DNSEP and GPSPE were both remarkably shorter in the patients than those in the normal potent men (Po0.001, both). Compared with the control group, the mean amplitudes of GPSEP were significantly greater in the patient group (Po0.001), but not considerably on the amplitudes of DNSEP (P ¼ 0.229). After cream application, the latencies and amplitudes of both DNSEP and GPSEP were significantly prolonged and reduced, respectively, in the PLA cream subgroup (Po0.001, all). These results showed that hyperexcitable ejaculatory reflex neurological factor was linked to PPE, because of hypersensitivity of the penile, accelerated conduction and cortical amplification of the genital stimuli. The PLA cream could delay sensory latency and decrease glans penile hyperexcitability, which may be the mechanism for PPE treatment. -

Ft-Ft) FACE Width of Face (Zy-Zy) Morphological Height of Face (N-Gn

CRANIOFACIAL MEASUREMENT REGION HEAD Width of forehead (ft-ft) FACE Width of face (zy-zy) Morphological height of face (n-gn) Physiognomical height of face (n-sto) Height of lower face (sn-gn) Height of mandible (sto-gn) Height of chin (sl-gn) Height of lower profile (prn-gn) Distance between glabella and sub-nasale (g-sn) ORBITS Inter-canthal width (en-en) Binocular width (ex-ex) Length of eye fissure (ex-en) Endocanthion – facial midline (en-se) Pupil facial midline distance (pupil –se) Orbito-glabellar distance (ex-g) Height of eye fissure (ps-pi) Endocanthion-facial midline surface distance (en-se surface) NOSE Width of the nasal root (mf-mf) Width of nose (al-al) Width between facial insertion of alar base (ac-ac) Width of columella (sn’-sn’) Height of nose (n-sn) Length of nasal bridge (n-prn) Nasal tip protrusion (sn-prn) Width of nostril floor (sbal-sn) Thickness of ala (al’-al’) Length of ala (ac-prn) Length of columella (sn-c-) LIPS AND MOUTH Width of philtrum (cph-cph) Width of mouth (ch-ch) Height of upper lip (sn-sto) Height of cutaneous lip (sn-ls) Vermillion height of upper lip (ls-sto) Vermillion height of lower lip (sto-li) Height of cutaneous lower lip (li-sl) Lower lip height (sto-sl) Halves of labial fissure length (ch-sto) Table 1. Craniofacial anatomic regions and anthropometric measurements. Group ICC REGION MEASUREMENT 1 2 3 4 All groups HEAD Width of forehead (ft-ft) 84.4 (11.9) 87.6 (7.2) 89.8 (4.0) 91.3 (2.4) .723 FACE Width of face (zy-zy) 80.9 (8.4) 88.7 (2.7) 88.5 (4.5) 89.7 (10.72) .764 Morphological height