Forehead, Temple and Scalp Reconstruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recognizing When a Child's Injury Or Illness Is Caused by Abuse

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Recognizing When a Child’s Injury or Illness Is Caused by Abuse PORTABLE GUIDE TO INVESTIGATING CHILD ABUSE U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street NW. Washington, DC 20531 Eric H. Holder, Jr. Attorney General Karol V. Mason Assistant Attorney General Robert L. Listenbee Administrator Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Office of Justice Programs Innovation • Partnerships • Safer Neighborhoods www.ojp.usdoj.gov Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention www.ojjdp.gov The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Assistance; the Bureau of Justice Statistics; the National Institute of Justice; the Office for Victims of Crime; and the Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking. Recognizing When a Child’s Injury or Illness Is Caused by Abuse PORTABLE GUIDE TO INVESTIGATING CHILD ABUSE NCJ 243908 JULY 2014 Contents Could This Be Child Abuse? ..............................................................................................1 Caretaker Assessment ......................................................................................................2 Injury Assessment ............................................................................................................4 Ruling Out a Natural Phenomenon or Medical Conditions -

Nasolabial and Forehead Flap Reconstruction of Contiguous Alar

Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery (2017) 70, 330e335 Nasolabial and forehead flap reconstruction of contiguous alareupper lip defects Jonathan A. Zelken a,b, Sashank K. Reddy c, Chun-Shin Chang a, Shiow-Shuh Chuang a, Cheng-Jen Chang a, Hung-Chang Chen a, Yen-Chang Hsiao a,* a Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taipei, Taiwan b Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Breastlink Medical Group, Laguna Hills, CA, USA c Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA Received 4 May 2016; accepted 31 October 2016 KEYWORDS Summary Background: Defects of the nasal ala and upper lip aesthetic subunits can be Nasal reconstruction; challenging to reconstruct when they occur in isolation. When defects incorporate both Nasolabial flap; the subunits, the challenge is compounded as subunit boundaries also require reconstruc- Rhinoplasty; tion, and local soft tissue reservoirs alone may provide inadequate coverage. In such cases, Forehead flap we used nasolabial flaps for upper lip reconstructionandaforeheadflapforalarrecon- struction. Methods: Three men and three women aged 21e79 years (average, 55 years) were treated for defects of the nasal ala and upper lip that resulted from cancer (n Z 4) and trauma (n Z 2). Unaffected contralateral subunits dictated the flap design. The upper lip subunit was excised and replaced with a nasolabial flap. The flap, depending on the contralateral reference, determined accurate alar base position. A forehead flap resurfaced or replaced the nasal ala. Autologous cartilage was used in every case to fortify the forehead flap reconstruction. Results: Patients were followed for 25.6 months (range, 1e4 years). -

Temporo-Mandibular Joint (Tmj) Dysfunction

Office: (310) 423-1220 BeverlyHillsENT.com Fax: (310) 423-1230 TEMPORO-MANDIBULAR JOINT (TMJ) DYSFUNCTION You may not have heard of it, but you use it hundreds of times every day. It is the Temporo- Mandibular Joint (TMJ), the joint where the mandible (the lower jaw) joins the temporal bone of the skull, immediately in front of the ear on each side of your head. You move the joint every time you chew or swallow. You can locate this joint by putting your finger on the triangular structure in front of your ear. Then move your finger just slightly forward and press firmly while you open your jaw all the way and shut it. The motion you feel is the TMJ. You can also feel the joint motion in your ear canal. These maneuvers can cause considerable discomfort to a patient who is having TMJ trouble, and physicians use these maneuvers with patients for diagnosis. TMJ Dysfunction can cause the following symptoms: Ear pain Sore jaw muscles Temple/cheek pain Jaw popping/clicking Locking of the jaw Difficulty in opening the mouth fully Frequent head/neck aches The pain may be sharp and searing, occurring each time you swallow, yawn, talk, or chew, or it may be dull and constant. It hurts over the joint, immediately in front of the ear, but pain can also radiate elsewhere. It often causes spasms in the adjacent muscles that are attached to the bones of the skull, face, and jaws. Then, pain can be felt at the side of the head (the temple), the cheek, the lower jaw, and the teeth. -

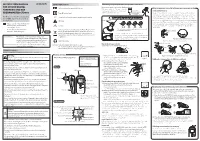

Instruction Manual for Citizen Digital Forehead And

INSTRUCTION MANUAL Symbol Explanations Measuring body temperature (temperature detection) Remove the probe cap and check the probe tip. FOR CITIZEN DIGITAL Refer to instruction manual before use. How to measure correctly in the ear measurement mode * When using it for the first time, open the FOREHEAD AND EAR battery cap and remove the insulation Open the Temperature basics battery cap to THERMOMETER CTD710 Type BF applied part sheet under the battery cap. remove the All objects radiate heat. This device consists of a probe with a built-in insulation sheet. infrared sensor that measures body temperature by detecting the heat Thank you very much for purchasing IP22 Classification for water ingress and particulate matter. radiated by the eardrum and surrounding tissue. Figure 4 shows the the CITIZEN digital forehead and ear Keeping the probe window clean tortuous anatomy of a normal ear canal. As shown in Figure 5, hold the thermometer. Warning Probe window ear and gently pull it back at an angle or pull it straight back to straighten out the ear canal. The shape of the ear canal differs from individual, check • Please read all of the information in before measurement. Accurate temperature measurements make it this instruction manual before Caution essential to straighten the ear canal so that the probe tip directly faces operating the device. the eardrum. • Be sure to have this instruction Indicates this device is subject to the Waste Electrical and Dirt in the probe window will impact the accuracy of temperature detection. External auditory manual to hand during use. 1902LA Electronic Equipment Directive in the European Union. -

Clinical Indicators: Acoustic Neuroma Surgery

Clinical Indicators: Acoustic Neuroma Surgery Approach Procedure CPT Days1 Infratemporal post-auricular approach to middle cranial fossa 61591 90 Transtemporal approach to posterior cranial fossa 61595 90 Transcochlear approach to posterior cranial fossa 61596 90 Transpetrosal approach to posterior cranial fossa 61598 90 Craniectomy for cerebellopontine angle tumor 61520 90 Craniectomy, transtemporal for excision of cerebellopontine angle 61526 90 tumor Combined with middle/posterior fossa craniotomy/ 61530 90 craniectomy Definitive Procedure CPT Days Resection of neoplasm, petrous apex, intradural, including dural 61606 90 repair Resection of neoplasm, posterior cranial fossa, intradural, including 61616 90 repair Microdissection, intracranial 61712 90 Stereotactic radiosurgery 61793 90 Decompression internal auditory canal 69960 90 Removal of tumor, temporal bone middle fossa approach 69970 90 Repair Procedure CPT Days Secondary repair of dura for CSF leak, posterior fossa, by free tissue 61618 90 graft Secondary repair of dura for CSF leak, by local or regional flap or 61619 90 myocutaneous flap Decompression facial nerve, intratemporal; lateral to geniculate 69720 90 ganglion Total facial nerve decompression and/or repair (may include graft) 69955 90 Abdominal fat graft 20926 90 Fascia lata graft; by stripper 20920 90 Fascia lata graft; by incision and area exposure, complex or sheet 20922 90 Intraoperative Nerve Monitoring Procedure CPT Days Auditory nerve monitoring, setup 92585 90 1 RBRVS Global Days Intraoperative neurophysiology testing, hourly 95920 90 Facial nerve monitoring, setup 95925 90 Indications 1. History a) Auditory complaints • hearing loss • fullness • distorted sound perception b) Tinnitus • ringing • humming • hissing • crickets c) Disequilibrium • unsteadiness • dizziness • imbalance • vertigo d) Headache e) Fifth and seventh cranial nerve symptoms • facial pain • facial tingling, numbness • tics • weakness f) Family history of neurofibromatosis type II g) Diplopia h) Dysarthria, dysphasia, aspiration, hoarseness 2. -

Ear and Forehead Thermometer

Ear and Forehead Thermometer INSTRUCTION MANUAL Item No. 91807 19.PJN174-14_GA-USA_HHD-Ohrthermometer_DSO364_28.07.14 Montag, 28. Juli 2014 14:37:38 USAD TABLE OF CONTENTS No. Topic Page 1.0 Definition of symbols 5 2.0 Application and functionality 6 2.1 Intended use 6 2.2 Field of application 7 3.0 Safety instructions 7 3.1 General safety instructions 7 3.3 Environment for which the DSO 364 device is not suited 9 3.4 Usage by children and adolescents 10 3.5 Information on the application of the device 10 4.0 Questions concerning body temperature 13 4.1 What is body temperature? 13 4.2 Advantages of measuring the body tempera- ture in the ear 14 4.3 Information on measuring the body tempera- ture in the ear 15 5.0 Scope of delivery / contents 16 6.0 Designation of device parts 17 7.0 LCD display 18 8.0 Basic functions 19 8.1 Commissioning of the device 19 8.2 Warning indicator if the body temperature is 21 too high 2 19.PJN174-14_GA-USA_HHD-Ohrthermometer_DSO364_28.07.14 Montag, 28. Juli 2014 14:37:38 TABLE OF CONTENTS USA No. Topic Page 8.3 Backlighting / torch function 21 8.4 Energy saving mode 22 8.5 Setting °Celsius / °Fahrenheit 22 9.0 Display / setting time and date 23 9.1 Display of time and date 23 9.2 Setting time and date 23 10.0 Memory mode 26 11.0 Measuring the temperature in the ear 28 12.0 Measuring the temperature on the forehead 30 13.0 Object temperature measurement 32 14.0 Disposal of the device 33 15.0 Battery change and information concerning batteries 33 16.0 Cleaning and care 36 17.0 “Cleaning” warning indicator 37 18.0 Calibration 38 19.0 Malfunctions 39 20.0 Technical specification 41 21.0 Warranty 44 3 19.PJN174-14_GA-USA_HHD-Ohrthermometer_DSO364_28.07.14 Montag, 28. -

Implications to Occipital Headache

The Journal of Neuroscience, March 6, 2019 • 39(10):1867–1880 • 1867 Neurobiology of Disease Non-Trigeminal Nociceptive Innervation of the Posterior Dura: Implications to Occipital Headache X Rodrigo Noseda, Agustin Melo-Carrillo, Rony-Reuven Nir, Andrew M. Strassman, and XRami Burstein Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115 Current understanding of the origin of occipital headache falls short of distinguishing between cause and effect. Most preclinical studies involving trigeminovascular neurons sample neurons that are responsive to stimulation of dural areas in the anterior 2/3 of the cranium and the periorbital skin. Hypothesizing that occipital headache may involve activation of meningeal nociceptors that innervate the posterior 1⁄3 of the dura, we sought to map the origin and course of meningeal nociceptors that innervate the posterior dura overlying the cerebellum. Using AAV-GFP tracing and single-unit recording techniques in male rats, we found that neurons in C2–C3 DRGs innervate the dura of the posterior fossa; that nearly half originate in DRG neurons containing CGRP and TRPV1; that nerve bundles traverse suboccipital muscles before entering the cranium through bony canals and large foramens; that central neurons receiving nociceptive information from the posterior dura are located in C2–C4 spinal cord and that their cutaneous and muscle receptive fields are found around the ears, occipital skin and neck muscles; and that administration of inflammatory mediators to their dural receptive field, sensitize their responses to stimulation of the posterior dura, peri-occipital skin and neck muscles. These findings lend rationale for the common practice of attempting to alleviate migraine headaches by targeting the greater and lesser occipital nerves with anesthetics. -

Livestock ID Product Catalog Int Ide Cover Ins Not Pr Do Table of Contents

Livestock ID Product Catalog INSIDE COVER DO NOT PRINT Table of Contents Z Tags Z1 No-Snag-Tag® Premium Tags .........................................02 Z Tags The New Z2 No-Tear-Tag™ System .....................................04 We’ve joined forces to bring you Temple Tag Herdsman® Two Piece Tags ........................................06 the best tags in the business. Z Tags Feedlot Tags..........................................................................08 Datamars is a worldwide leader in high-performance livestock identification Temple Tag Feeder Tags ...................................................................10 systems. With its state-of-the-art global manufacturing facilities and Temple Tag Original Tag .................................................................. 12 worldwide technical expertise, Datamars has added Temple Tag® and Z Tags® Temple Tag CalfHerder™ Tag ............................................................ 13 to the company’s global portfolio of world-class brands. Temple Tag FaStocker® Tag ..............................................................14 ComfortEar® Radio Frequency Identification Tags (RFID) ...........16 Datamars can bring you new and improved products faster than ever before. Temple Tag & Z Tags Taggers and Accessories .............................18 But one thing hasn’t changed, and that’s our unwavering commitment to America’s livestock producers. Temple Tag & Z Tags Custom Tag Decoration ..............................20 Temple Tag & Z Tags Hot Stamp Machines ................................... -

Core Strength Exercises

CORE STRENGTH EXERCISES • The main muscles involved with Core Strength include muscles of the abdomen, hip flexors and low back postural muscles. • It is important to maintain proper strength of these muscles to prevent and rehabilitate from low back / pelvic dysfunction and pain. • All of these exercises should be comfortable and not produce pain or discomfort. Bracing: The Key to preventing low back injuries Abdominal Bracing – Lying down • Lie down, face up with your knees bent and feet on floor. • Contract your stomach muscles so that you imagine pushing your low back to the floor or that you are pulling your belly button to your spine. Abdominal Bracing - Standing • Stand up straight and place one hand on the small of the back and one hand on your abdomen. • Bend Forward at the waist and feel the lower back muscles contract (extensors). • Come back up to neutral to relax the low back muscles. • You will feel the low back muscles contract when you contract your abdominal and gluteal muscles. Bracing technique and curling • Lay on the ground on your back. • One leg is bent and the other leg remains flat on the floor. Your hands can be on your chest or at your side. • Fix your eyes on a spot on the ceiling directly above you. • Tighten your stomach muscles. • Holding the stomach contraction, lift your shoulder blades and head off the floor while looking at that spot on the ceiling. Hold for 3-10 seconds and repeat three times. • Switch leg positions and repeat the technique. Beginner to Intermediate position • Position yourself on your hands and knees with your pelvis and thighs at 90 degrees and upper back and arms at 90 degrees. -

Facial Image Comparison Feature List for Morphological Analysis

Disclaimer: As a condition to the use of this document and the information contained herein, the Facial Identification Scientific Working Group (FISWG) requests notification by e-mail before or contemporaneously to the introduction of this document, or any portion thereof, as a marked exhibit offered for or moved into evidence in any judicial, administrative, legislative, or adjudicatory hearing or other proceeding (including discovery proceedings) in the United States or any foreign country. Such notification shall include: 1) the formal name of the proceeding, including docket number or similar identifier; 2) the name and location of the body conducting the hearing or proceeding; and 3) the name, mailing address (if available) and contact information of the party offering or moving the document into evidence. Subsequent to the use of this document in a formal proceeding, it is requested that FISWG be notified as to its use and the outcome of the proceeding. Notifications should be sent to: Redistribution Policy: FISWG grants permission for redistribution and use of all publicly posted documents created by FISWG, provided the following conditions are met: Redistributions of documents, or parts of documents, must retain the FISWG cover page containing the disclaimer. Neither the name of FISWG, nor the names of its contributors, may be used to endorse or promote products derived from its documents. Any reference or quote from a FISWG document must include the version number (or creation date) of the document and mention if the document is in a draft status. Version 2.0 2018.09.11 Facial Image Comparison Feature List for Morphological Analysis 1. -

Human Sacrifice and Mortuary Treatments in the Great Temple of Tenochtitlán

FAMSI © 2007: Ximena Chávez Balderas Human Sacrifice and Mortuary Treatments in the Great Temple of Tenochtitlán Research Year: 2005 Culture: Mexica Chronology: Postclassic Location: México City, México Site: Tenochtitlán Table of Contents Introduction The bone collection in study Human sacrifice and mortuary treatments Methodology Osteobiography Tafonomic analysis Sacrifice by heart extraction Decapitation: Trophy skulls, Tzompantli skulls and elaboration of skull masks Skull masks Population analysis based upon DNA extraction Preliminary results Final considerations List of Figures Sources Cited Introduction The present report describes the study undertaken with the osteologic collection obtained from the Great Temple excavations in Tenochtitlán; this collection was assembled in the interval from 1978 to 2005. The financial support granted to us by FAMSI enabled the creation of four lines of research: 1) packing and preventive conservation; 2) osteobiography; 3) mortuary treatments; and 4) population genetics. Immediately, a detailed exposition of the work and its results up to the present moment will be given. Submitted 11/16/2006 by: Ximena Chávez Balderas [email protected] Figure 1. General view of the archaeological zone of the Great Temple in México City. 2 The bone collection in study For the present study the human remains found in 19 offerings in the Great Temple of Tenochtitlán were analyzed. This place symbolizes the axis mundi for the Mexicas. The deposits were temporarily situated in the period comprehended between 1440 and 1502 A.D., which corresponds mostly to stage IVb (1469-1481 A.D.). The total number of bodies studied was 1071. From these, seventy-four were recovered in the context of offerings and correspond to skull masks, decapitated skulls, tzompantli skulls, isolated remains and a primary context. -

Knowledge of Skull Base Anatomy and Surgical Implications of Human Sacrifice Among Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican Cultures

See the corresponding retraction, DOI: 10.3171/2018.5.FOCUS12120r, for full details. Neurosurg Focus 33 (2):E1, 2012 Knowledge of skull base anatomy and surgical implications of human sacrifice among pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures RAUL LOPEZ-SERNA, M.D.,1 JUAN LUIS GOMEZ-AMADOR, M.D.,1 JUAN BArgES-COLL, M.D.,1 NICASIO ArrIADA-MENDICOA, M.D.,1 SAMUEL ROMERO-VArgAS, M.D., M.SC.,2 MIGUEL RAMOS-PEEK, M.D.,1 MIGUEL ANGEL CELIS-LOPEZ, M.D.,1 ROGELIO REVUELTA-GUTIErrEZ, M.D.,1 AND LESLY PORTOCArrERO-ORTIZ, M.D., M.SC.3 1Department of Neurosurgery, Instituto Nacional de Neurologia y Neurocirugia “Manuel Velasco Suárez;” 2Department of Spine Surgery, Instituto Nacional de Rehabilitación; and 3Department of Neuroendocrinology, Instituto Nacional de Neurologia y Neurocirugia “Manuel Velasco Suárez,” Mexico City, Mexico Human sacrifice became a common cultural trait during the advanced phases of Mesoamerican civilizations. This phenomenon, influenced by complex religious beliefs, included several practices such as decapitation, cranial deformation, and the use of human cranial bones for skull mask manufacturing. Archaeological evidence suggests that all of these practices required specialized knowledge of skull base and upper cervical anatomy. The authors con- ducted a systematic search for information on skull base anatomical and surgical knowledge among Mesoamerican civilizations. A detailed exposition of these results is presented, along with some interesting information extracted from historical documents and pictorial codices to provide a better understanding of skull base surgical practices among these cultures. Paleoforensic evidence from the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan indicates that Aztec priests used a specialized decapitation technique, based on a deep anatomical knowledge.