Adaptive Leadership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After Editing

Shackleton Dates AUGUST 8th 1914 The team leave the UK on the ship, Endurance. DEC 5th 1914 They arrive at the edge of the Antarctic pack ice, in the Weddell Sea. JAN 18th 1915 Endurance becomes frozen in the pack ice. OCT 27TH 1915 Endurance is crushed in the ice after drifting for 9 months. Ship is abandoned and crew start to live on the pack ice. NOV 1915 Endurance sinks; men start to set up a camp on the ice. DEC 1915 The pack ice drifts slowly north; Patience camp is set up. MARCH 23rd 2016 They see land for the first time – 139 days have passed; the land can’t be reached though. APRIL 9th 2016 The pack ice starts to crack so the crew take to the lifeboats. APRIL 15th 1916 The 3 crews arrive on ELEPHANT ISLAND where they set up camp. APRIL 24th 1916 5 members of the team, including Shackleton, leave in the lifeboat James Caird, on an 800 mile journey to South Georgia, for help. MAY 10TH 1916 The James Caird crew arrive in the south of South Georgia. MAY 19TH -20TH Shackleton, Crean and Worsley walk across South Georgis to the whaling station at Stromness. MAY 23RD 1916 All the men on Elephant Island are safe; Shackleton starts on his first attempt at a rescue from South Georgia but ice prevents him. AUGUST 25th Shackleton leaves on his 4th attempt, on the Chilian tug boat Yelcho; he arrives on Elephant Island on August 30th and rescues all his crew. MAY 1917 All return to England. -

JOURNAL Number Six

THE JAMES CAIRD SOCIETY JOURNAL Number Six Antarctic Exploration Sir Ernest Shackleton MARCH 2012 1 Shackleton and a friend (Oliver Locker Lampson) in Cromer, c.1910. Image courtesy of Cromer Museum. 2 The James Caird Society Journal – Number Six March 2012 The Centennial season has arrived. Having celebrated Shackleton’s British Antarctic (Nimrod) Expedition, courtesy of the ‘Matrix Shackleton Centenary Expedition’, in 2008/9, we now turn our attention to the events of 1910/12. This was a period when 3 very extraordinary and ambitious men (Amundsen, Scott and Mawson) headed south, to a mixture of acclaim and tragedy. A little later (in 2014) we will be celebrating Sir Ernest’s ‘crowning glory’ –the Centenary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic (Endurance) Expedition 1914/17. Shackleton failed in his main objective (to be the first to cross from one side of Antarctica to the other). He even failed to commence his land journey from the Weddell Sea coast to Ross Island. However, the rescue of his entire team from the ice and extreme cold (made possible by the remarkable voyage of the James Caird and the first crossing of South Georgia’s interior) was a remarkable feat and is the reason why most of us revere our polar hero and choose to be members of this Society. For all the alleged shenanigans between Scott and Shackleton, it would be a travesty if ‘Number Six’ failed to honour Captain Scott’s remarkable achievements - in particular, the important geographical and scientific work carried out on the Discovery and Terra Nova expeditions (1901-3 and 1910-12 respectively). -

JCS Newsletter – Issue 23 · Summer 2017

JCS 2017(EM) Quark2017.qxp_Layout 2 14/08/2017 16:43 Page 1 The James Caird Society Newsletter Issue 23 · Summer 2017 The draughtsmanship behind a legend Read the story of the James Caird that lies behind the one we all know ... (Page 4/5) Registered Charity No. 1044864 JCS 2017(EM) Quark2017.qxp_Layout 2 14/08/2017 16:43 Page 2 James Caird Society news and events New Chairman Friday 17 November This year sees a new Chairman of the The AGM will be held at James Caird Society. At the November 5.45pm in the AGM Rear Admiral Nick Lambert will James Caird Hall take over from Admiral Sir James at Dulwich College Perowne KBE who has been an and will include the inspirational chairman since 2006, appointment of a new overseeing several major JCS Society Chairman landmarks including the Nimrod Ball and, The lecture will begin at most recently in 2016, a series of 7pm in the Great Hall. magnificent events to celebrate the The speaker will be Centenary of the Endurance Expedition. Geir Klover, Director of the We wish James well and hope we will still Fram Museum Oslo, who see him at the Lecture/Dinner evenings. will talk about Amundsen Nick Lambert joined the Royal Navy as Dinner will be served aseamaninMarch1977,subsequently afterwards gaining an honours degree in Geography at the University of Durham in 1983. He spent much time at sea, including on HM ships Birmingham, Ark Royal, Cardiff, Meetings in 2018 and has commanded HMS Brazen and HMS Newcastle. May Dinner He was captain of the ice patrol ship Endurance from 2005 to 2007, deploying Friday 11 May for two deeply rewarding seasons in Antarctica, after which he commanded Task Force 158 in the North Arabian Gulf, tasked with the protection of Iraq’s AGM and dinner economically vital offshore oil infrastructure. -

Ernest Shackleton and the Epic Voyage of the Endurance

9-803-127 REV: DECEMBER 2, 2010 NANCY F. KOEHN Leadership in Crisis: Ernest Shackleton and the Epic Voyage of the Endurance For scientific discovery give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel give me Amundsen; but when disaster strikes and all hope is gone, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton. — Sir Raymond Priestley, Antarctic Explorer and Geologist On January 18, 1915, the ship Endurance, carrying a highly celebrated British polar expedition, froze into the icy waters off the coast of Antarctica. The leader of the expedition, Sir Ernest Shackleton, had planned to sail his boat to the coast through the Weddell Sea, which bounded Antarctica to the north, and then march a crew of six men, supported by dogs and sledges, to the Ross Sea on the opposite side of the continent (see Exhibit 1).1 Deep in the southern hemisphere, it was early in the summer, and the Endurance was within sight of land, so Shackleton still had reason to anticipate reaching shore. The ice, however, was unusually thick for the ship’s latitude, and an unexpected southern wind froze it solid around the ship. Within hours the Endurance was completely beset, a wooden island in a sea of ice. More than eight months later, the ice still held the vessel. Instead of melting and allowing the crew to proceed on its mission, the ice, moving with ocean currents, had carried the boat over 670 miles north.2 As it moved, the ice slowly began to soften, and the tremendous force of distant currents alternately broke apart the floes—wide plateaus made of thousands of tons of ice—and pressed them back together, creating rift lines with huge piles of broken ice slabs. -

Ridge Class Week 3 English

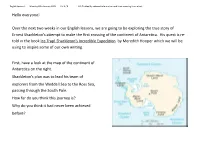

English Lesson 1 Monday 18th January 2021 Yrs 5 / 6 LO: To identify relevant information and infer meaning from a text Hello everyone! Over the next two weeks in our English lessons, we are going to be exploring the true story of Ernest Shackleton’s attempt to make the first crossing of the continent of Antarctica. His quest is re- told in the book Ice Trap! Shackleton’s Incredible Expedition by Meredith Hooper which we will be using to inspire some of our own writing. First, have a look at the map of the continent of Antarctica on the right. Shackleton’s plan was to lead his team of explorers from the Weddell Sea to the Ross Sea, passing through the South Pole. How far do you think this journey is? Why do you think it had never been achieved before? English Lesson 1 Monday 18th January 2021 Yrs 5 / 6 LO: To identify relevant information and infer meaning from a text Now, listen to Ice Trap! and look at the illustrations, thinking carefully about the men on the Expedition: What do you think they were thinking and feeling at different points in their journey? How did their moods change? What are the main themes of the story? Would you have acted differently if you had been on the expedition? Why / Why not? Click on the link ‘Ice Trap video’ in the Ridge folder which has been emailed to your family. When you have listened to Ice Trap!, answer the eight questions on the next pages. Answer in full sentences. -

Ernest Shackleton and the Epic Voyage of the Endurance

9-803-127 REV: DECEMBER 2, 2010 NANCY F. KOEHN Leadership in Crisis: Ernest Shackleton and the Epic Voyage of the Endurance For scientific discovery give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel give me Amundsen; but when disaster strikes and all hope is gone, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton. — Sir Raymond Priestley, Antarctic Explorer and Geologist On January 18, 1915, the ship Endurance, carrying a highly celebrated British polar expedition, froze into the icy waters off the coast of Antarctica. The leader of the expedition, Sir Ernest Shackleton, had planned to sail his boat to the coast through the Weddell Sea, which bounded Antarctica to the north, and then march a crew of six men, supported by dogs and sledges, to the Ross Sea on the opposite side of the continent (see Exhibit 1).1 Deep in the southern hemisphere, it was early in the summer, and the Endurance was within sight of land, so Shackleton still had reason to anticipate reaching shore. The ice, however, was unusually thick for the ship’s latitude, and an unexpected southern wind froze it solid around the ship. Within hours the Endurance was completely beset, a wooden island in a sea of ice. More than eight months later, the ice still held the vessel. Instead of melting and allowing the crew to proceed on its mission, the ice, moving with ocean currents, had carried the boat over 670 miles north.2 As it moved, the ice slowly began to soften, and the tremendous force of distant currents alternately broke apart the floes—wide plateaus made of thousands of tons of ice—and pressed them back together, creating rift lines with huge piles of broken ice slabs. -

April 6, 1917 – November 11, 1918)

Some World War I Veterans Connected with Jackson County, Kansas (April 6, 1917 – November 11, 1918) A work in progress as of June 27, 2017, by Dan Fenton 1 Some World War I Veterans Connected with Jackson County, Kansas (April 6, 1917 – November 11, 1918) Abbott, Carl.1 Carl C. Abbott, private in Company C, 40th Regiment Infantry; enlisted on June 27, 1917, at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri; discharged on March 12, 1918 on account of a physical disability at the Base Hospital, Fort Riley, Kansas. Box 1.10 Carl Clarence Abbott. “OHIO PVT CO C 40 INFANTRY WORLD WAR I” Born May 5, 1898; Died May 12, 1957. Buried in Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery, Akron, Ohio. www.findagrave.com. Abbott, Paul.1 Born in Holton, Kansas, enlisted on September 22, 1917 at Minneapolis, Minnesota; served in France as a private in Company D, 61st Infantry, wounded in right leg. Box 1.10 “August 8, 1918. Dear Mother and kids: I received your letters of July 7 yesterday. It took them just a month to get here. … We have just returned from the trenches to our rest camp, which is about three miles from the trenches. We were about 300 feet from the German trenches, but the only Germans I have seen yet, were some prisoners further inland. The trenches are about a foot above my head at most places, having lookout posts and dugouts at various points. I have been put in an automatic squad. This squad consists of two automatic rifle teams, and the corporal. Each team has one automatic rifleman and two carriers. -

Students Relive Antarctic Exploration

Students Relive Antarctic Exploration By Patricia Brhel seals, fatty and fishy, that they the difference in their struggle to Third Officer Alfred Cheetham, Zoe hunted and ate when food and sup- survive. Several mentioned never Congdon as Chief Engineer Louis If you squinted a little and their plies for the humans ran out. wanting to see the cold again. Rickinson, Aidan Setlock as Second voices had been a bit deeper, you’d They skillfully answered ques- When they returned from this Engineer A.J. Kerr, EamonColbert have thought that it was the crew of tions about friendship, about Percy expedition most of the men became –Auble as Surgeon Dr. James the Endurance that had formed a Blackburrows initial status as a caught up in World War I and never McIlroy,Kyle Fearon as Surgeon Dr. panel to answer questions and dis- stowaway. They described saw each other again. Shackleton Alexander Macklin, Morgan cuss their time, from 1914 to 1916, Shackletons attempts to keep up died of a heart attack in 1921. The Thayer as Biologist Robert Clark, stranded in Antarctica along with group moral with games such as students also noted that no one has Garrett Breen as Meteorologist their commander, Sir Ernest hockey and football, music, dog ever found a trace of the Leonard Hussey, Mikayla Shackleton. races and assigned chores before he Endurance. It still lies on the ocean McMahon as Physicist Reginald Thanks to some vintage clothing took off to look for help. The group floor just off the coast of James, Jacob Engle as Motor and props, and coaching by talked about a number of times Antarctica. -

The Enduring Books of Shackleton's Endurance

The Enduring Books of Shackleton’s Endurance: A Polar Reading Community at Sea David H. Stam Introduction After twenty years of Antarctic centenary anniversaries celebrating the “heroic age” of polar exploration, and its eponymous “heroes” Fridtjof Nansen, Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, Douglas Mawson, Ernest Shackleton, and others, it hardly seems necessary to recount yet again the story of Ernest Shackleton’s “epic voyage” of Endurance and his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-16 (ITAE). Its praises have been sung and its faults analyzed constantly during this period by hagiographers and debunkers and just about everyone in between. Materials have appeared in print, in movies, documentaries, exhibitions, in poetry and song, in comics and ceramics, among management gurus, in art, on cigarette cards, even in philately. The source of much of this attention, in North America at least, was a 1999 exhibition simply called “Shackleton” at New York’s American Museum of Natural History, and a large literature immediately followed.1 In this study, I have tried to draw together all of the known documentary evidence about the book history and reading experiences of the journey. In effect, I am retelling the story of Endurance from the perspective of a reading community. The framework for the narrative begins with the role of Shackleton himself as the community leader, as a consummate bookman, an early and voracious reader, and an eager consumer of poetry who claimed to prefer history to fiction. Roland Huntford sums up Shackleton’s early literary appetite thus: Shackleton, at any rate, was proving to be at home with all kinds of men, but he was still “old Shacks” always “busy with his books”. -

Civil War Manuscripts

CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS MANUSCRIPT READING ROW '•'" -"•••-' -'- J+l. MANUSCRIPT READING ROOM CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS A Guide to Collections in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress Compiled by John R. Sellers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 1986 Cover: Ulysses S. Grant Title page: Benjamin F. Butler, Montgomery C. Meigs, Joseph Hooker, and David D. Porter Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Civil War manuscripts. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: LC 42:C49 1. United States—History—Civil War, 1861-1865— Manuscripts—Catalogs. 2. United States—History— Civil War, 1861-1865—Sources—Bibliography—Catalogs. 3. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division—Catalogs. I. Sellers, John R. II. Title. Z1242.L48 1986 [E468] 016.9737 81-607105 ISBN 0-8444-0381-4 The portraits in this guide were reproduced from a photograph album in the James Wadsworth family papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. The album contains nearly 200 original photographs (numbered sequentially at the top), most of which were autographed by their subjects. The photo- graphs were collected by John Hay, an author and statesman who was Lin- coln's private secretary from 1860 to 1865. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. PREFACE To Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War was essentially a people's contest over the maintenance of a government dedi- cated to the elevation of man and the right of every citizen to an unfettered start in the race of life. President Lincoln believed that most Americans understood this, for he liked to boast that while large numbers of Army and Navy officers had resigned their commissions to take up arms against the government, not one common soldier or sailor was known to have deserted his post to fight for the Confederacy. -

Final Exercises Program

One Hundred and Ninety-Second FINAL EXERCISES The Class of 2021 May 21-23, 2021 Contents Finals Programs, 2 Board of Visitors, 6 Administration, 7 Graduates and Degree Candidates* Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, 8 College of Arts & Sciences, 11 School of Medicine, 22 School of Law, 24 School of Engineering & Applied Science, 25 School of Education and Human Development, 31 Darden Graduate School of Business Administration, 34 School of Architecture, 36 School of Nursing, 37 Darden Graduate School of Business Administration & McIntire School of Commerce, 38 McIntire School of Commerce, 39 School of Continuing & Professional Studies, 41 Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, 41 School of Data Science, 42 Student and Faculty Awards, 43 Honorary Societies, 44 The Good Old Song, outside back cover *The degree candidates in this program were applicants for degrees as of May 1, 2021. The August 2020 and December 2020 degree recipients precede the list of May 2021 degree candidates in each section. © 2021 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia Designed by University of Virginia Printing and Copying Services Finals Program Friday, May 21, 2021, 10 a.m. School of Medicine, School of Education and Human Development, School of Nursing, Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy Academic Procession Elizabeth K. Meyer, Grand Marshal Degree Candidates and Faculty President’s Party The Pledge of Allegiance The National Anthem Performed by Blair A. Smith and Owen K. Wilson, Members of the Class of 2021 Welcome James E. Ryan, President of the University of Virginia Introduction of Finals Speaker James B. -

{TEXTBOOK} Shackleton

SHACKLETON PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Roland Huntford | 800 pages | 21 Sep 1989 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780349107448 | English | London, United Kingdom Ernest Shackleton - Wikipedia Available on Amazon. Added to Watchlist. Best Man vs Nature movies. Share this Rating Title: Shackleton 7. Use the HTML below. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Episodes Seasons. Nominated for 1 Golden Globe. Edit Cast Series cast summary: Kenneth Branagh Franks 2 episodes, Paul Humpoletz Man in Audience 2 episodes, Phoebe Nicholls Emily Shackleton 2 episodes, Eve Best Eleanor Shackleton 2 episodes, Mark Tandy Frank Shackleton 2 episodes, Cicely Delaney Cecily Shackleton 2 episodes, Christian Young Raymond Shackleton 2 episodes, Embeth Davidtz Rosalind Chetwynd 2 episodes, Gino Melvazzi Head Waiter 2 episodes, Danny Webb Perris 2 episodes, Lorcan Cranitch Frank Wild 2 episodes, Michael Culkin Jack Morgan 2 episodes, Mark McGann Tom Crean 2 episodes, Abby Ford Marcie 2 episodes, Ron Donachie Keltie 2 episodes, Corin Redgrave Lord Curzon 2 episodes, Robert Swann Freshfield 2 episodes, Chris Larkin George Marston 2 episodes, Elizabeth Spriggs Janet Stancombe Wills 2 episodes, Peter Cartwright Judge 2 episodes, Ben Silverstone Very Young Applicant 2 episodes, Shaun Dooley Hubert Hudson 2 episodes, Nicholas Rowe Thomas Orde-Lees 2 episodes, Richard Cant First Lieutenant 2 episodes, Mathew Ashwood Second Lieutenant 2 episodes, Mark Williams Dudley Docker 2 episodes, Roger May Cavalry Officer 2 episodes, Hal Cruttenden Bearded Applicant 2 episodes,