A2 Historic and Settlement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[HA.NTS.] FA R 408 [POST OFFICB • O FARMERS Continued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2139/ha-nts-fa-r-408-post-officb-o-farmers-continued-42139.webp)

[HA.NTS.] FA R 408 [POST OFFICB • O FARMERS Continued

[HA.NTS.] FA R 408 [POST OFFICB • o FARMERS continued. tShotter Robert, Selborne, Alton, East Spencer William, Picket's hill, Stand- Rowland J. HartIeyWestpall, Winchfld Worldham ford, Headley, Petersfield Ruddle George, Kingsclere, Newbury Shrimpton G.Bishopstoke,Southampton Spicer William, Burley, Ringwood Ruddle H.(exors.of),Kingsclere,New bry ShrimptonJoho, Exton,Bishop'sWalthm Spier J ames, Binsted, Alton Ruddle WiHiam,Killgsclere,Woodlands, ShrimptonJ.jun.Exton,Bishop'sWalthm Spier William, Cliddesden, Basingstoke Newbury SHlence Mrs. C. Compton, Winchester Spratt George, CrondaIl, Farnham Ruttell Lawrence,Cove,Farnboro' station Sillence J ames,Otterbourne,Winchester Spratt J ames, Fritham, Lyndhurst Ruffell Lawrence, Elvetham,Winchfield Silvester Henry, Curbridge, Swanwick, Stacey C. T. Lyeway. Ropley, Alresford Ruffell Lawrence~iun.Hawley,Farnboro' Titchfield, Southampton Stacey Thomas, Pamber, Basingstoke Rumble George, Wallinl1:ton~ Fareham Silvester H. Upper'Lanham,OldAlresford Stadden John, Abbott'8 Ann, Andover Rumbold John, ItchingsweII, Newbury Silvester J. Slade, Froxfield, Petersfield Standfield Richard, Saltern's hill, Rumbold J oseph.. White house,Sydmon- Silvester Richard, New place, Soberton, Bealllieu, Southampton ton, Newbury Bishop's Waltham StandfieldW.J.Fording-bridge,SalisbllrJ- RumbollA.Church Oakley. Basingstoke Simmonds Geo. Mount Pleasant, Sway, Stanfield Joseph, Throop. Holden- RumboIl J.North Waltham,Micheldever Lymington hurst, Christchurch Rummery Joseph, West Minley, Farn- SimmonsJ. Weston, Freshwater, 1. ofW Standing Henry, Winsor, Southampton, borough station tSimpsonJ. Upper Froyle, Froyle, Alton Stanley George, Pamber, Basingstoke RummingJohn, Kingsclere,Woodlands, Sims Frauds, North Hayling, Havant Stares George, Hipley, Fareham Newlmry Sims Harry, North Hayling, Bavant Stares Henry,Bedenham farm, Fareham Rumsey George, Shipton Bellinger, Singleton George, Swanmore, Bishop's Stares Henry, Forest gate. Hambledon~ 1\'1arlborouO"h Waltham Horn Dean Rumsey Rt. -

Week Ending 12Th February 2010

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 06 Week Ending: 12th February 2010 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column For the Northern Area to: For the Southern Area to: Head of Planning Head of Planning Beech Hurst Council Offices Weyhill Road Duttons Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ ROMSEY SO51 8XG In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 10/00166/FULLN Erection of two replacement 33 And 34 Andover Road, Red Mr & Mrs S Brown Jnr Mrs Lucy Miranda YES 08.02.2010 dwellings together with Post Bridge, Andover, And Mr R Brown Page ABBOTTS ANN garaging and replacement Hampshire SP11 8BU 12.03.2010 and resiting of entrance gates 10/00248/VARN Variation of condition 21 of 11 Elder Crescent, Andover, Mr David Harman Miss Sarah Barter 10.02.2010 TVN.06928 - To allow garage Hampshire, SP10 3XY 05.03.2010 ABBOTTS ANN to be used for storage room -

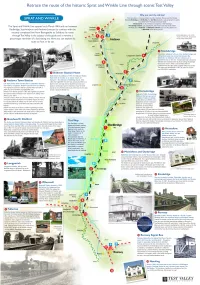

Sprat and Winkle Line Leaflet

k u . v o g . y e l l a v t s e t @ e v a e l g d t c a t n o c e s a e l P . l i c n u o C h g u o r o B y e l l a V t s e T t a t n e m p o l e v e D c i m o n o c E n i g n i k r o w n o s n i b o R e l l e h c i M y b r e h t e g o t t u p s a w l a i r e t a m e h T . n o i t a m r o f n I g n i d i v o r p r o f l l e s d n i L . D r M d n a w a h s l a W . I r M , n o t s A H . J r M , s h p a r g o t o h p g n i d i v o r p r o f y e l r e s s a C . R r M , l l e m m a G . C r M , e w o c n e l B . R r M , e n r o H . M r M , e l y o H . R r M : t e l f a e l e l k n i W d n a t a r p S e h t s d r a w o t n o i t a m r o f n i d n a s o t o h p g n i t u b i r t n o c r o f g n i w o l l o f e h t k n a h t o t e k i l d l u o w y e l l a V t s e T s t n e m e g d e l w o n k c A . -

Planning Services

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 47 Week Ending: 23rd November 2018 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column Head of Planning and Building Beech Hurst Weyhill Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 18/03025/TREEN Fell Fir Tree encroaching on Pollyanna, Little Ann Road, Mr Patrick Roberts Mr Rory Gogan YES 19.11.2018 Cherry tree; T1 Ash and T2 Little Ann, Andover Hampshire 21.12.2018 ABBOTTS ANN Ash both showing signs of SP11 7SN desease and some dieback (see full description on form) 18/03018/FULLN Change of use from Telford Gate, Unit 1 , Mr Ricky Sumner, RSV Mr Luke Benjamin 19.11.2018 factory/warehouse to general Hopkinson Way, Portway Services 12.12.2018 ANDOVER TOWN industrial to include vehicle Business Park, Andover SP10 (HARROWAY) repairs and servicing and 3SF MOT testing 18/03067/CLEN -

Planning Services

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 3 Week Ending: 19th January 2018 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column Head of Planning and Building Beech Hurst Weyhill Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 18/00002/FULLN Single storey rear extension 1 Danebury Mews , Salisbury Mr Andrew Thompson Miss Katherine 18.01.2018 Road, Abbotts Ann, SP11 7NX Dowle ABBOTTS ANN 13.02.2018 18/00141/FULLN Installation of satellite dish to Pollyanna , Little Ann Road, Mr Patrick Roberts Mrs Donna Dodd YES 16.01.2018 elevation of modern Little Ann, SP11 7SN 16.02.2018 ABBOTTS ANN extension and removal of existing aerial 18/00142/LBWN Installation of satellite dish to Pollyanna , Little Ann Road, Mr Patrick Roberts Mrs Donna Dodd YES 16.01.2018 elevation of modern Little Ann, SP11 7SN 16.02.2018 ABBOTTS ANN extension -

Longparish Cemetery

Cemetery analysis Graves located on Cemetery extension map NOTE: Due to earlier formatting it looks like many of the dates have automatically become the first of the month Reservations Born Burial Grave Burial Grant Burial Grant Grave Reservation Notice of Certificate Fee for Application Fee for Date of death Date of Burial Surname Forenames Occupation Abode Age (calculated) Register xl cemetery map number from paperwork Number Date completed number fee In accounts Undertaker interment burial/cremation burial In accounts for memorial Stonemason memorial in accounts Inscription Notes 21/06/1905 Taylor Dorothy 86 1819 No 29/03/1932 Sawyer Susan Longparish 45 1887 513 02/04/1932 Newell Fanny Longparish 85 1847 516 04/05/1932 Smith George Longparish 36 1896 515 04/05/1932 Guyatt Jane Wherwell 76 1856 514 13/05/1932 Cockcraft Albert Red Roofs, Longparish 59 1873 517 02/06/1932 Ralph Sarah Longparish 77 1855 518 11/06/1932 Malt Eliza Forton, Longparish 77 1855 519 19 09/03/31 19 15/08/1932 Tubbs Walter Charles Owls Lodge, Longparish 59 1873 520 22/08/1932 White Dorothy Eileen Longparish 5 1927 521 01/12/1932 Brackstone Alice Longparish 67 1865 522 05/12/1932 Harmer George William Tree Tops, Wherwell 77 1855 523 16/01/1933 Alexander Jane District Villas, Longparish 50 1883 524 18/01/1933 Mason Arthur Firgrove, Longparish 37 1896 525 23/01/1933 Ball Ellen Longparish 81 1852 526 27/03/1933 Walker stillborn child of Stanley & Edith Longparish 0 1933 527 29/04/1933 Sweatman Jemima Fox Farm, Longparish 90 1843 529 5 07/10/25 6 29/04/1933 Carter Joseph -

A CRITICAL EVALUATION of the LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD of the CHALK UPLANDS of NORTHWEST EUROPE Lesley

A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD OF THE CHALK UPLANDS OF NORTHWEST EUROPE The Chilterns, Pegsdon, Bedfordshire (photograph L. Blundell) Lesley Blundell UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD September 2019 2 I, Lesley Blundell, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: 3 4 Abstract Our understanding of early human behaviour has always been and continues to be predicated on an archaeological record unevenly distributed in space and time. More than 80% of British Lower-Middle Palaeolithic findspots were discovered during the late 19th/early 20th centuries, the majority from lowland fluvial contexts. Within the British planning process and some academic research, the resultant findspot distributions are taken at face value, with insufficient consideration of possible bias resulting from variables operating on their creation. This leads to areas of landscape outside the river valleys being considered to have only limited archaeological potential. This thesis was conceived as an attempt to analyse the findspot data of the Lower-Middle Palaeolithic record of the Chalk uplands of southeast Britain and northern France within a framework complex enough to allow bias in the formation of findspot distribution patterns and artefact preservation/discovery opportunities to be identified and scrutinised more closely. Taking a dynamic, landscape = record approach, this research explores the potential influence of geomorphology, 19th/early 20th century industrialisation and antiquarian collecting on the creation of the Lower- Middle Palaeolithic record through the opportunities created for artefact preservation and release. -

Esconet Text Retrieval System

EscoNet Text Retrieval System TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL - PLANNING SERVICES WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 7 Week Ending: Friday, 15 February 2002 Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING to arrive before the expiry date shown in the last column For the Northern Area (TVN) to: For the Southern Area (TVS) to Head of Planning Head of Planning Council Offices 'Beech Hurst' Duttons Road Weyhill Road ROMSEY SO51 8XG ANDOVER SPIO 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection PLANNING APPLICATIONS APPLICATION NO. / PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER / REGISTRATION DATE PUBLICITY EXPIRY DATE http://www.minutes.org.uk/cgi-bin/cgi003.exe?Y,20020101,20021231,00000...,,,15.02.02,6138848,6235415,1,000000050202,1,1,1,P,23001392,0,00,00,N (1 of 9) [20/06/2013 13:49:04] EscoNet Text Retrieval System TVN.07863/1 Outline - Erection of three detached Land off Abbotts Hill, ABBOTTS Washington And Company Elizabeth Walker 15.02.2002 dwellings ANN 15.03.2002 TVN.08405 Erection of two storey extension to 74a Charlton Road, Andover Mr And Mrs Holloway Beryl Burgess 11.02.2002 south west elevation to provide HARROWAY 12.03.2002 kitchen and dining room with two bedrooms over TVN.A.00586 Installation of two single Bus shelter opposite Shepherds Adshel Gavin Spiller 12.02.2002 illuminated advertisement panels Spring School, Smannell Road, 12.03.2002 forming an integral part of a bus Andover ALAMEIN -

Gazetteer.Doc Revised from 10/03/02

Save No. 91 Printed 10/03/02 10:33 AM Gazetteer.doc Revised From 10/03/02 Gazetteer compiled by E J Wiseman Abbots Ann SU 3243 Bighton Lane Watercress Beds SU 5933 Abbotstone Down SU 5836 Bishop's Dyke SU 3405 Acres Down SU 2709 Bishopstoke SU 4619 Alice Holt Forest SU 8042 Bishops Sutton Watercress Beds SU 6031 Allbrook SU 4521 Bisterne SU 1400 Allington Lane Gravel Pit SU 4717 Bitterne (Southampton) SU 4413 Alresford Watercress Beds SU 5833 Bitterne Park (Southampton) SU 4414 Alresford Pond SU 5933 Black Bush SU 2515 Amberwood Inclosure SU 2013 Blackbushe Airfield SU 8059 Amery Farm Estate (Alton) SU 7240 Black Dam (Basingstoke) SU 6552 Ampfield SU 4023 Black Gutter Bottom SU 2016 Andover Airfield SU 3245 Blackmoor SU 7733 Anton valley SU 3740 Blackmoor Golf Course SU 7734 Arlebury Lake SU 5732 Black Point (Hayling Island) SZ 7599 Ashlett Creek SU 4603 Blashford Lakes SU 1507 Ashlett Mill Pond SU 4603 Blendworth SU 7113 Ashley Farm (Stockbridge) SU 3730 Bordon SU 8035 Ashley Manor (Stockbridge) SU 3830 Bossington SU 3331 Ashley Walk SU 2014 Botley Wood SU 5410 Ashley Warren SU 4956 Bourley Reservoir SU 8250 Ashmansworth SU 4157 Boveridge SU 0714 Ashurst SU 3310 Braishfield SU 3725 Ash Vale Gravel Pit SU 8853 Brambridge SU 4622 Avington SU 5332 Bramley Camp SU 6559 Avon Castle SU 1303 Bramshaw Wood SU 2516 Avon Causeway SZ 1497 Bramshill (Warren Heath) SU 7759 Avon Tyrrell SZ 1499 Bramshill Common SU 7562 Backley Plain SU 2106 Bramshill Police College Lake SU 7560 Baddesley Common SU 3921 Bramshill Rubbish Tip SU 7561 Badnam Creek (River -

King's Somborne Footpath Walks 2014

King’s Somborne Footpath Walks 2014 The programme of footpath walks listed below is as of 1 January 2014 and may be subject to change throughout the year. Please refer to the village website (www.thesombornes.org.uk – Directory – Footpath Walk) for the latest information. Sunday 26 January 2014 2:00pm King’s Somborne Village Hall 5½ miles (8¾ Km) 2¼ hours We leave the village along Winchester Road and up Red Hill before turning onto the path past Ashley New buildings. At the crossroads we take the path across the field past Ashley Manor Farm and then over the hill to Chalk Vale before returning to the village past the beef unit and back along Winchester Road. Sunday 23 February 2014 2:00pm King’s Somborne Village Hall 4¾ miles (7½ Km) 2 hours We cross Palace Field and alongside the churchyard to pick up the Clarendon Way alongside Cow Drove Hill. We follow the Clarendon Way past How Park and across the water meadows to Houghton. From Houghton, it is road walking past the site of Bossington village before taking the footpath along the line of the Roman road to Horsebridge and the footpath back to the village. Sunday 30 March 2014 2:00 pm King’s Somborne Village Hall 6 miles (9½ Km) 2½ hours We leave the village along Winchester Road and take the path past the Beef Unit. We continue towards Up Somborne before turning left to take the steep path down to Little Somborne. At Little Somborne we head North to North Park Farm and the path back towards the village. -

36 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

36 bus time schedule & line map 36 Lockerley View In Website Mode The 36 bus line (Lockerley) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Lockerley: 12:51 PM (2) Romsey: 9:26 AM - 1:26 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 36 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 36 bus arriving. Direction: Lockerley 36 bus Time Schedule 23 stops Lockerley Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Bus Station, Romsey Tuesday 12:51 PM Council O∆ces, Romsey Church Place, Romsey Wednesday Not Operational Malthouse Close, Romsey Thursday 12:51 PM Malthouse Close, Romsey Friday Not Operational Priestlands, Romsey Saturday Not Operational Greatbridge Road, Romsey Fishlake Meadows, Romsey Dukes Head, Belbins 36 bus Info Direction: Lockerley Timsbury Institute, Timsbury Stops: 23 Trip Duration: 34 min Recreation Ground, Michelmersh Line Summary: Bus Station, Romsey, Council O∆ces, Romsey, Malthouse Close, Romsey, Priestlands, Mannyngham Way, Michelmersh Romsey, Fishlake Meadows, Romsey, Dukes Head, Belbins, Timsbury Institute, Timsbury, Recreation Hill View Road, Michelmersh Ground, Michelmersh, Mannyngham Way, Michelmersh, Hill View Road, Michelmersh, Brickworks, Michelmersh, Bear And Ragged Staff, Brickworks, Michelmersh Kimbridge, Mottisfont Abbey, Mottisfont, Bengers Lane, Mottisfont, Village Hall, Mottisfont, Russell Bear And Ragged Staff, Kimbridge Drive, Dunbridge, Awbridge School, Kents Oak, Church Lane, Awbridge, Wood Farm, Kents Oak, Mottisfont Abbey, Mottisfont Newtown, Doctor's -

M+W Sites List (HF000007092018)

Hampshire County Council Site Code Site Name Grid Ref Operator / Agent Site Description Site Status Site Narrative (* = Safeguarded), (†=Chargeable site) Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council BA009 Newnham Common 470336 Hampshire County Council Landfill (restored) Site completed Restored non-inert landfill, closed in 1986 but subject to leachate monitoring not monitored (closed site, low priority) 153471 BA017† Apple Dell 451004 Portals Landfill (inert) Lapsed permission Dormant; deposit of non-toxic cellulose waste from paper making processes for a period of ten years (BDB46323) (Agriculture - 2009) Permission expired, no monitoring. Overton 148345 BA018* Wade Road 465127 Basingstoke Skip Hire, Hampshire County Council, Waste Processing, HWRC Active Waste transfer, including construction, demolition, industrial, household and clinical waste and household waste recycling centre; extension and improvement of household waste recycling Basingstoke 153579 Veolia Environmental Services (UK) Plc centre (BDB/60584); erection of waste recycling building (BDB/61845); erection of extension to existing waste recycling building (BDB/64564); extension and improvement of household waste recycling centre (BDB/69806) granted 12.2008 - 2 monitoring visits per year. BA019* Chineham Energy Recovery Facility 467222 Veolia Environmental Services (UK) Plc Waste Processing (energy Active Energy recovery incinerator (BDB044300) commissioned in autumn 2002 with handover in January 2003; the incinerator has the capacity to process at least 90,000 tonnes a year,