Reducing Double-Crested Cormorant Damage in Wisconsin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RETURN of HERRING GULLS to NATAL COLONY by JAMES PINSON LUVWXG Overa Periodof 32 Years,F

Bird-Banding 68] LUDWIG,Return ofHerring Gulls April RETURN OF HERRING GULLS TO NATAL COLONY BY JAMES PINSON LUVWXG Overa periodof 32 years,F. E. Ludwig,C. C. Ludwig,C. A. Ludwig,and I havebanded 60,000 downy young Herring Gulls (Larusarqentatus) in coloniesin LakesHuron, Michigan, and Superior.I havegrouped the coloniesaccording to geographical locationin sevenareas (See Table 1). From thesecolonies as of July1961 we have recovered 47 adults(See Tables 2, 3, and4 for eachrecovery) which were banded as chicks.All of theseadults werein full adult plumage,and I have assumedthat they were breedingin thecolonies where we found them. Six questionable re- coveries have been noted. TABLE 1. THE AREASAND THEIR COLONIES In Lake Huron 1. Saginaw Bay area-- Little Charity Island 4404-08328 2. Thunder Bay area-- Black River Island 4440-08318 Scarecrow Island 4450-08320 SulphurIsland 4500-08322 GrassyIsland 4504-08325 SugarIsland 4506-08318 Thunder Bay Island 4506-08317 Gull Island 4506-08318 3. Rogers City area-- Calcite Pier colony 4530-08350 4. Straits of Mackinac area-- Goose Island 4555-08426 St. Martin's Shoal 4557-08434 Green Island 4551-08440 In Lake Michigan 5. Beaver Islands' area-- Hatt Island 4549-08518 Shoe Island 4548-08518 Pismire Island 4547-08527 Grass Island 4547-08528 Big Gull Island 4545-08540 6. Grand Traverse Bay area-- Bellows' Island 4506-08534 In Lake Superior 7. Grand Marais area-- Grand Marais Island 4640-08600 Latitude - Longitude Thesenumbers (e.g. 4500 - 08320) are the geo- graphicalcoordinates of the islands. An anlysisof therecoveries reveals that 19 (40.4percent) of the adultswere bandedin the samecolony as recovered,15 (32.1 per- cent)more recovered in the same area as banded, and 13 (27.5per- Bird Divisionof the Museumof Zoology,University of Michigan,Ann Arbor, Michigan Contributionfrom Universityof MichiganBiological Station. -

Phase II Status Assessment of Herpetofauna in the Saginaw Bay Watershed

Phase II Status Assessment of Herpetofauna in the Saginaw Bay Watershed July 25, 2013 Prepared for: Saginaw Basin Land Conservancy 809 East Midland Street Bay City, MI 48706 Prepared by: Herpetological Resource and Management, LLC P.O. Box 110 Chelsea, MI 48118 www.HerpRMan.com (313) 268-6189 Project Number: 12D-7.01 Suggested Citation: Mifsud, David A. 2013. Phase II Status Assessment of Herpetofauna in the Saginaw Bay Watershed. Herpetological Resource and Management Report 2012 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ 5 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 8 Site Locations and Descriptions .................................................................................. 10 Methods ....................................................................................................................... 19 Historical Review and Site Assessment ................................................................... 19 Herpetofaunal Surveys ........................................................................................... 20 Results and Discussion ................................................................................................ 22 1) Au Gres Delta Nature Preserve ......................................................................... -

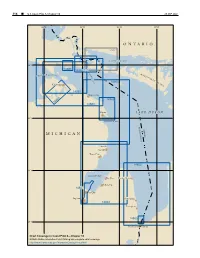

M I C H I G a N O N T a R

314 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 6, Chapter 10 26 SEP 2021 85°W 84°W 83°W 82°W ONTARIO 2251 NORTH CHANNEL 46°N D E 14885 T 14882 O U R M S O F M A C K I N A A I T A C P S T R N I A T O S U S L A I N G I S E 14864 L A N Cheboygan D 14881 Rogers City 14869 14865 14880 Alpena L AKE HURON 45°N THUNDER BAY UNITED ST CANADA MICHIGAN A TES Oscoda Au Sable Tawas City 14862 44°N SAGINAW BAY Bay Port Harbor Beach Sebewaing 14867 Bay City Saginaw Port Sanilac 14863 Lexington 14865 43°N Port Huron Sarnia Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 6—Chapter 10 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 6, Chapter 10 ¢ 315 Lake Huron (1) Lawrence, Great Lakes, Lake Winnipeg and Eastern Chart Datum, Lake Huron Arctic for complete information.) (2) Depths and vertical clearances under overhead (12) cables and bridges given in this chapter are referred to Fluctuations of water level Low Water Datum, which for Lake Huron is on elevation (13) The normal elevation of the lake surface varies 577.5 feet (176.0 meters) above mean water level at irregularly from year to year. During the course of each Rimouski, QC, on International Great Lakes Datum 1985 year, the surface is subject to a consistent seasonal rise (IGLD 1985). -

RR-545- East Central Michigan Transportation Study

HE • .. 'i no, \ T'' ~- .. ' ' ' 'n·,.'' ·i :r: i ' I ' EAST CENTRAL MICHIGAN TRANSPORTATION STUDY ,_ PRESENTED BY THE MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION IN COOPERATION WITH THE EAST CENTRAL MICHIGAN PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT REGION . ., I . ' J.P. WOODFORD, DIRECTOR ·~ I I MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION June, 1979 This report represents the findings and/or professional opinions of the Michigan Department of Transportation staff and is not an official opinion of the Michigan Transportation Commission. MICHIGAN TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION Hannes Meyers, Jr. , Cl;lairman Carl V . Pellonpaa Weston E. Vivian Lawrence C. Patrick, Jr. William C . Marshall Rodger D. Young Director John P. Woodford i L -1- ; I ·.J l: ' I CNI'ARIC I -w L I " i' f i \ § I c--i\ LI - -~ (_ i }; MINNESOTA ( ....... r \' i IOWA I PENNSYLVANIA .I ' II..I..INCIS I CHIC -- I NOlANA MISSOURI KENTUCKY / ----- ~-;__ ____ / REGION 7 LOCATION MAP MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION I ' ' TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE -- A. Introduction ..•.. ~ • . • . • • . • • • . • • • . • . • • • . • • • • 1 Study Area • . • • . • . • . • • . • . • • • • • • • • 1 Purpose of_ Study ......•••.........• , .....•••••••• , • • 1 B. Planning Technique ........•.•••••..•.••.•...........••• , , 3 C. Analysis Techniques •...........•.....••...•.•....•.••• ; • • 6 D. Transportation Issues Goals and Objectives ••....•.•••••• ~- 9-------- -··--....... ___ Discussion of Issues Identified at Pre-Study Meetings . • . • . • . • • • • • • • • . • • • • • . • . • . • 10 State Transportation Goals -

Charity Island Partnership Agreement

Huron Pines 4241 Old US 27 South, Suite 2; Gaylord, MI 49735 | [email protected] | (989) 448-2293 Charity Islands Phragmites Management Project 2016 Partnership Agreement Between Huron Pines U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) The Nature Conservancy Saginaw Bay Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area (CISMA) Saginaw Valley State University (SVSU) Au Gres-Sims School District Great Lakes Stewardship Initiative (GLSI) Michigan Sea Grant Michigan Natural Features Inventory (MNFI) Michigan Department of Natural Resources (Michigan DNR) Charity Island Transport, Inc. Purpose This Partnership Agreement outlines a long-term plan for managing non-native Phragmites australis at the Charity Islands. The main goal of this project is to restore sensitive wetland habitat and protect native plant and animal species, including the state- and federally-threatened Pitcher’s thistle. Other objectives include supporting ongoing university research, providing place-based outdoor education opportunities for local K-12 students, raising public awareness about invasive species, and preserving the scenic and recreational of the Charity Islands. The Agreement summarizes project activities that have already been completed and clarifies partner roles and responsibilities for the timeframe 2016 through 2018. This Agreement updates and supersedes the 2015 Charity Islands Phragmites Management Partnership Agreement and will be considered valid through the end of 2018, upon which it will be reviewed and updated as necessary to cover anticipated activities and partner roles beyond the end of the 2018 treatment season. Project Background The Charity Islands are located in Saginaw Bay, approximately 12 miles east of the City of Au Gres and 10 miles northwest of the City of Caseville, and are part of Arenac County. -

Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan

Chapter 3: The Environment Chapter 3: The Environment In this chapter: Introduction Climate Island Types, Geology and Soils Archeological and Cultural Values Social and Economic Context Environmental Contaminants Natural Resources Associated Plans and Initiatives Habitat Management Visitor Services Archaeological and Cultural Resources Management Law Enforcement Throughout this document, five national wildlife refuges (NWRs, refuges) are discussed individually—such as the Gravel Island NWR or the Green Bay NWR. This document also discusses all five NWRs collectively as one entity and when doing so, refers to the group as the “Great Lakes islands refuges” or “Great Lakes islands NWRs.” Introduction General Island Geological and Ecological Background Michigan and Wisconsin are fortunate to have many islands that form a “waterscape” unlike any found elsewhere in the world. Of the three Upper Great Lakes (Huron, Michigan, and Superior), there exists approximately 200 islands within the confines of the states in Lake Huron, 76 in Lake Michigan, and 175 in Lake Superior (not counting 86 in the St. Mary’s River) (Soule, 1993). The glacial history of island chains differs across the Upper Great Lakes. Glacial till overlying limestone bedrock forms the bulk of the Beaver Island group in northern Lake Michigan, although Pismire Island (part of Michigan Islands NWR) is an example of a sand and gravel bar island. Conversely, most islands in Lake Superior are formed of igneous and metamorphic bedrock, with the Huron Islands (of Huron NWR) being the result of granite upthrusts (Soule, 1993). Post-glacial history of these islands also varies. National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS, Refuge System) records indicate that many of the islands of Michigan Islands NWR were either impacted by human habitation (Gull Island) or by other uses (e.g., Hat Island was used as bombing range prior to refuge establishment) (Gates, 1950). -

Act 451 of 1994 SUBCHAPTER 3 FISHERIES CHARTER and LIVERY BOATS PART 445 CHARTER and LIVERY BOAT SAFETY 324.44501 Definitions

NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION ACT (EXCERPT) Act 451 of 1994 SUBCHAPTER 3 FISHERIES CHARTER AND LIVERY BOATS PART 445 CHARTER AND LIVERY BOAT SAFETY 324.44501 Definitions. Sec. 44501. As used in this part: (a) "Boat livery" means a place of business or any location where a person rents or offers for rent any vessel other than a nonmotorized raft to the general public for noncommercial use on the waters of this state. Boat livery does not include a place where a person offers cabins, cottages, motel rooms, hotel rooms, or other similar rental units if vessels are furnished only for the use of persons occupying the units. (b) "Carrying passengers for hire" or "carry passengers for hire" means the transporting of any individual on a vessel other than a nonmotorized raft for consideration directly or indirectly paid to the owner of the vessel, the owner's agent, the operator of the vessel, or any other person who holds any interest in the vessel. (c) "Charter boat" means a vessel other than a nonmotorized raft that is rented or offered for rent to carry passengers for hire if the owner or the owner's agent retains possession, command, and control of the vessel. (d) "Class A vessel" means a vessel, except a sailboat, that carries for hire on navigable waters not more than 6 passengers. (e) "Class B vessel" means a vessel, except a sailboat, that carries for hire on inland waters not more than 6 passengers. (f) "Class C vessel" means a vessel, except a sailboat, that carries for hire on inland waters more than 6 passengers. -

Michigan Islands National Wildlife Refuge (Lake Huron Islands Managed by Shiawassee NWR)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Michigan Islands National Wildlife Refuge (Lake Huron islands managed by Shiawassee NWR) Habitat Management Plan October 2018 Little Charity Island 2013. (Photo credit: USFWS) Michigan Islands NWR: Shiawassee NWR Habitat Management Plan Habitat Management Plans provide long-term guidance for management decisions; set forth goals, objectives, and strategies needed to accomplish refuge purposes; and, identify the Fish and Wildlife Service’s best estimate of future needs. These plans detail program planning levels that are sometimes substantially above current budget allocations and as such, are primarily for Service strategic planning and program prioritization purposes. The plans do not constitute a commitment for staffing increases, operational and maintenance increases, or funding for future land acquisition. The National Wildlife Refuge System, managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is the world's premier system of public lands and waters set aside to conserve America's fish, wildlife, and plants. Since the designation of the first wildlife refuge in 1903, the System has grown to encompass more than 150 million acres, 556 national wildlife refuges and other units of the Refuge System, plus 38 wetland management districts. Michigan Islands NWR: Shiawassee NWR Habitat Management Plan Table of Contents Signature Page .................................................................................................................................ii Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................. -

Lake Huron Citizens Fishery Advisory Committee Meeting Minutes

Lake Huron Citizens Fishery Advisory Committee Established by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, to improve and maintain fishery resources of Lake Huron through better communication and partnership. Lake Huron Citizens Fishery Advisory Committee Minutes August 19, 2008 RAM Conference Center 10:00 a.m. – 3:00 p.m. Approved November 5, 2008 Attendees: Paul Wendler, Forrest Williams, Todd Williams, Frank Krist, Ken Merckel, Jim DeClerck, Ron Ramsey, Ed Retherford, Andy Pelt, Clarence Smith, Bill Jenkins, Judy Ogden, Jerry Lawrence, Dave Johnson, Jim Baker, Jim Johnson, Dave Borgeson, Larry DeSloover, Kurt Newman. 10:00 Welcome and introductions (Paul Wendler): Paul Wendler called the meeting to order asking for any additional agenda items. Paul then announced he was retiring as chairman of the Advisory Committee. He was proud of the committee and its independent and free thinking nature, and the manner in which it represented the various constituencies of Lake Huron. Paul said that he would run today’s meeting, and proposed that after lunch the committee should elect a new chairman, with Frank Krist receiving Paul’s recommendation. Kurt Newman then introduced himself and described his background. Kurt earned his undergraduate degree from Michigan State University, a master’s degree at Virginia Tech University, and returned to MSU for his PhD. Kurt joined the DNR in 1998 working on tribal related issues. Kurt then headed up the Habitat Management Unit in the MDNR Fisheries, working heavily in the hydropower negotiation process. Kurt then became the Lake Erie Basin Coordinator in 2002, resulting in his deep involvement in all things Great Lakes (core member of Great Lakes Fisheries Commission Board of Technical Experts, core member of Sea Lamprey Integration Committee, etc.). -

T—4042 Disposal Options For

T—4042 DISPOSAL OPTIONS FOR CONTAMINATED SEDIMENTS IN SAGINAW BAY, MICHIGAN: CONFINED DISPOSAL FACILITIES AND BASIC EXTRACTION SLUDGE TREATMENT by Maureen Y. Jordan ProQuest Number: 10783717 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10783717 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 T—4042 A thesis submitted to the Faculty and the Board of Trustees of the Colorado School of Mines in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Mineral Resources Ecology). Golden, Colorado Signed: Approved: -OT-*/&+'<■Q Dr. E. A. Howard Thesis Advisor Golden, Colorado Date Environmental Sciences and Engineering Ecology Department ii T-4042 ABSTRACT Lake sediment is a significant source of water pollution in the Great Lakes. Contaminants present in the water column eventually accumulate in the sediments where they are adsorbed on the surfaces of the sediment grains. Resuspension of the sediment and remobilization of the contaminants can occur through wind and wave action caused by various types of natural and manmade disturbances. Disposal of dredged contaminated sediments in the Great Lakes is a major problem due to the enormous volume of material involved. -

Data from the 2006 International Piping Plover Census

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Data from the 2006 International Piping Plover Census Data Series 426 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Data from the 2006 International Piping Plover Census By Elise Elliott-Smith and Susan M. Haig, U.S. Geological Survey, and Brandi M. Powers, U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Data Series 426 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Elliott-Smith, E., Haig, S.M., and Powers, B.M., 2009, Data from the 2006 International Piping Plover Census: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 426, 332 p. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 -

Double-Crested Cormorant Damage Management in Michigan

FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT: DOUBLE-CRESTED CORMORANT DAMAGE MANAGEMENT IN MICHIGAN Prepared By: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE ANIMAL AND PLANT HEALTH INSPECTION SERVICE WILDLIFE SERVICES In Cooperation with: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE and the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE SLEEPING BEAR DUNES NATIONAL LAKESHORE June 2011 SUMMARY The United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services (USDA, APHIS, WS), the United States Department of the Interior (USDI), Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and the USDI National Park Service, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore have prepared an Environmental Assessment (EA) on alternatives for the management of Double-crested Cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus, DCCO) damage in Michigan. Increases in the North American DCCO population, and subsequent range expansion have resulted in complaints of DCCO damage to property, aquaculture, and public resources (e.g., co-nesting colonial waterbirds, sport and commercial fish populations, and vegetation), and risks to human health and safety (e.g., risk of DCCO collisions with aircraft). This EA analyzes the need for cormorant damage management (CDM) in Michigan and five alternatives for meeting the need for action including implementation of the Public Resource Depredation Order (PRDO) (50 CFR 21.48) as promulgated by the USFWS. Alternatives considered include: 1) continuing the current CDM program including implementation of the PRDO (No Action Alternative); 2) Implementing an adaptive management program proposed by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources and Environment (MDNR); 3) implementing an adaptive management program proposed by the MDNR with a limit on annual DCCO take intermediate to the current program and the MDNR proposal; 4) Restricting Federal agency CDM to the use of nonlethal methods; and 5) Discontinuing CDM by Federal agencies.