The Girl with the Wrong Name

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Hope's Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder in Hope Donahue's

HOPE’S OBSESSIVE–COMPULSIVE DISORDER IN HOPE DONAHUE’S BEAUTIFUL STRANGER AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By ROMAULI BUTAR BUTAR Student Number: 024214034 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2010 HOPE’S OBSESSIVE–COMPULSIVE DISORDER IN HOPE DONAHUE’S BEAUTIFUL STRANGER AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By ROMAULI BUTAR BUTAR Student Number: 024214034 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2010 i A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis HOPE’S OBSESSIVE–COMPULSIVE DISORDER IN HOPE DONAHUE’S BEAUTIFUL STRANGER By ROMAULI BUTAR BUTAR Student Number: 024214034 Approved by Drs. Hirmawan Wijanarka, M.Hum. August 20, 2010 Advisor Adventina Putranti, S.S. M.Hum. August 20, 2010 Co-Advisor ii A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis HOPE’S OBSESSIVE–COMPULSIVE DISORDER IN HOPE DONAHUE’S BEAUTIFUL STRANGER By ROMAULI BUTAR BUTAR Student Number: 024214034 Defended before the Board of Examiners on 30 August 2010 and Declared Acceptable BOARD OF EXAMINERS Name Signature Chairman : Dr. Francis Borgias Alip, M.Pd., M.A. ______________________ Secretary : Drs. Hirmawan Wijanarka, M.Hum. ______________________ Member : Maria Ananta Tri Suryandari, S.S. ______________________ Member : Drs. Hirmawan Wijanarka, M.Hum. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

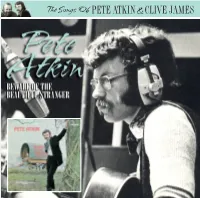

The Songs of PETE ATKIN&CLIVE JAMES

EDSS 1029 PA BOTBS booklet 6/1/09 17:38 Page 2 EDSS 1029 The Songs Of PETE ATKIN&CLIVE JAMES 28 1 EDSS 1029 PA BOTBS booklet 6/1/09 17:38 Page 4 Beware Of The Beautiful Arranged by Pete Atkin Project co-ordination – Val Jennings Strings arranged by Nick Harrison CD package – Jools at Mac Concept Stranger Produced by Don Paul CD mastering – Alchemy Engineered by Tom Allom Ephemera courtesy of the collections of Fontana 6309 011, 1970. Re-issued on RCA Recorded at Regent Sound A, Tottenham Pete Atkin and Clive James SF 8387 in 1973 in a re-designed sleeve with CD front cover main photo and strapline photo – “Touch Has A Memory” replaced by “Be Street, London W1, on 31st March and 1st & 2nd April 1970 Sophie Baker Careful When They Offer You The Moon”, and Huge thanks – Pete Atkin, Clive James, Simon Mixed between 2 pm and 6 pm with “Sunrise” as the second song. Platz, Steve Birkill, Ronen Guha on 2nd April 1970 and Caroline Cook “Be Careful When They Offer You The Moon” and “A Man Who’s Been Around” For everything (and we mean everything) relating to were recorded at Tin Pan Alley Studio, Pete Atkin’s works, visit www.peteatkin.com, but Denmark Street on 11th August 1970 make sure you’ve got plenty of time to spend! Then of course, you’ll want to visit Credits – British Rail, Arthur Guinness, www.clivejames.com William Hazlitt, John Keats, Meade Lux Lewis, Garcia Lorca, Odham’s Junior Pete Atkin’s albums on the Encyclopaedia, Auguste Renoir, William Edsel label: Shakespeare and Duke Ellington (there never was another). -

Frontage Road 11.Pdf

Editor: Julie Fulbright Front cover photography by: Emily Gardner Graphic Design and Production: Tony Bartolo and Brenda Ellis Printer: Dockins Graphics, Cleveland, Tenn. Copyright: 2009 Cleveland State Community College All Rights Reserved Cleveland State Community College is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Ga. 30033-4097, telephone number (404) 679-4501. Cleveland State Community College is an Affirmative Action/ Equal Employment Opportunity (AA/EEO) institution committed to the education of a non-racially identifiable staff and student body. The college does not permit discrimination on the basis of race, color, religious views, veteran status, political affiliation, gender, age, national origin, orientation or disability against employees, students and guests in any college sponsored or hosted educational program or activity including, but not limited to, the following: recruitment; admissions; academic and other educational program activities; housing; facilities; access to course offerings; counseling; financial assistance; employment assistance; health and insurance benefits and services; rules for marital and parental status; student services; and athletics. CSCC HS/9082/4/1/09 Table of Contents Jean McCants Crockett And Does It? . 7 Julie Fulbright In Memory of Harry Dean. 8 Judy Nye World. 9 Suzanne and Fred Wood Dedication for Harry Dean. 10 Nancy Boyd A Tribute to Harry . 11 Chad Ehlers Understand Me. .12 Purpose Is the Cycle. .13 Love for Your Foe . 14 Wicked Is My World . 15 Tammy Jefferson A Portrait of Fiction. .16 My Love You.... .18 Valerie A. Edwards Pink Clouds . 19 Colors . 20 A to Z. 21 The Sea. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1990S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1990s Page 174 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1990 A Little Time Fantasy I Can’t Stand It The Beautiful South Black Box Twenty4Seven featuring Captain Hollywood All I Wanna Do is Fascinating Rhythm Make Love To You Bass-O-Matic I Don’t Know Anybody Else Heart Black Box Fog On The Tyne (Revisited) All Together Now Gazza & Lindisfarne I Still Haven’t Found The Farm What I’m Looking For Four Bacharach The Chimes Better The Devil And David Songs (EP) You Know Deacon Blue I Wish It Would Rain Down Kylie Minogue Phil Collins Get A Life Birdhouse In Your Soul Soul II Soul I’ll Be Loving You (Forever) They Might Be Giants New Kids On The Block Get Up (Before Black Velvet The Night Is Over) I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight Alannah Myles Technotronic featuring Robert Palmer & UB40 Ya Kid K Blue Savannah I’m Free Erasure Ghetto Heaven Soup Dragons The Family Stand featuring Junior Reid Blue Velvet Bobby Vinton Got To Get I’m Your Baby Tonight Rob ‘N’ Raz featuring Leila K Whitney Houston Close To You Maxi Priest Got To Have Your Love I’ve Been Thinking Mantronix featuring About You Could Have Told You So Wondress Londonbeat Halo James Groove Is In The Heart / Ice Ice Baby Cover Girl What Is Love Vanilla Ice New Kids On The Block Deee-Lite Infinity (1990’s Time Dirty Cash Groovy Train For The Guru) The Adventures Of Stevie V The Farm Guru Josh Do They Know Hangin’ Tough It Must Have Been Love It’s Christmas? New Kids On The Block Roxette Band Aid II Hanky Panky Itsy Bitsy Teeny Doin’ The Do Madonna Weeny Yellow Polka Betty Boo -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Madonna E Seu Acervo Multiartístico: Os Fetichismos Visuais Na Obra Do Maior Mito

Intercom – Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação 41º Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação – Joinville - SC – 2 a 8/09/2018 Madonna e seu Acervo Multiartístico: os fetichismos visuais na obra do maior mito 1 pop do século XX Rafael Nacif de Toledo PIZA2 Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro - UERJ Resumo O presente artigo pretende fazer uma retrospectiva da carreira da cantora Madonna, tendo como ponto de tensionamento os fetichismos visuais, conceito desenvolvido pelo italiano Massimo Canevacci em 2008. Nosso intuito é analisar o desenvolvimento cronológico da obra da cantora, relacionando suas iniciativas ao escopo teórico criado pelo sociólogo italiano, oferecendo pistas para decifrarmos os segredos de sua longevidade e do sucesso por trás de sua persona pública. Palavras-chave Madonna, cronologia, fetichismos visuais. Introdução Ser fã de Madonna é um privilégio e uma honra. Acompanhar a carreira de uma cantora, atriz, produtora, diretora de cinema, celebridade e personalidade é uma tarefa das mais prazerosas e dispendiosas. Montar uma coleção de objetos da Madonna pode custar alguns bons reais que poderiam ser investidos em outras coisas, como carros, roupas e outros itens de consumo. Mas deixando o lado mercantil de lado e focando na parte estética, o que Madonna nos apresenta é uma coleção de hits para as pistas de dança e baladas empacotados em formatos correspondentes às tecnologias do período, sempre com fotografias riquíssimas e figurinos ousados, tipologias inovadoras e designs de cair o queixo. Madonna e os fetichismos visuais de Canevacci Em 2008, Massimo Canevacci desenvolve “Fetichismos visuais: corpos erópticos e metrópole comunucacional” (Ateliê Editorial, 2008). -

An Analysis of Selected Music in Disney Princess Films by Gillian

“A Dream is a Wish Your Heart Makes”: An Analysis of Selected Music in Disney Princess Films by Gillian Downey A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Chemistry (Honors Scholar) Presented May 11, 2016 Commencement June 2016 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Gillian Downey for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Chemistry presented on May 11, 2016. Title: “A Dream is a Wish Your Heart Makes”: An Analysis of Selected Music in Disney Princess Films. Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ Patti Duncan The Disney Princesses are some of the most beloved and well-recognized characters in animation across the globe. Most of these characters sing throughout their movie. This essay analyzes what I refer to as the “I Want” song of several Disney Princesses. It is divided into three sections, one for each of the main themes described in these songs: true love, freedom, and self-acceptance. It was found that the Disney Princesses follow a basic chronological line in their desires. The oldest characters desire love, while the newest want to be happy with who they are inside. Because these films and their music have been treasured for decades, these characters can strongly influence viewers’ lives. Where appropriate, the potential impacts of choosing certain Disney Princesses for role models is discussed. An appendix is included with the lyrics for each analyzed song. Key Words: Disney, music, -

Beautiful Stranger Free

FREE BEAUTIFUL STRANGER PDF Christina Lauren | 352 pages | 06 Jun 2013 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781476731537 | English | New York, NY, United States Finally // Beautiful Stranger - Wikipedia An ex-chorus girl lives on the Beautiful Stranger, supported by a married man she doesn't know is a crook. Maxwell Setton John Beautiful Stranger. Marksman Productions Ltd. British Lion Films. USA UK. But after finding out he won't leave his wife for her, she becomes embroiled with potter Pierre Clement Jacques Bergerac. I didn't know anything about Beautiful Stranger also known as Twist of Fate apart from the fact that it stars Ginger Rogers in her first British film and was directed by David Miller, the man behind Sudden Fear which is a film I like. Therefore, I was interested to see what Beautiful Stranger had to offer and the answer to Beautiful Stranger question is Beautiful Stranger has a lot of potential but does nothing with it. She is there with financier Louis Galt who she plans to marry after his divorce is finalised. This quiet existence, however, is shaken up when Johnny discovers that…. She finds that he isn't as divorced as he had claimed, but doesn't realise that his faults run far deeper. She runs away from him and falls in love with Jacques Pierre Clemont, her real life Beautiful Strangerbut Beautiful Stranger Herbert Loma criminal who knows both Jacques and Louis Beautiful Stranger a spanner into the works and upsets the course of true love. The film depends heavily on coincidence, but Herbert Lom is rather good as nasty Emil. -

The Mix Song List

THE MIX SONG LIST CONTEMPORARY 2010’s CENTURIES/ fall out boy 24K MAGIC/ bruno mars CHAINED TO THE RHYTHM/ katy perry ADDICTED TO A MEMORY/ zedd CHANDELIER/ sia ADVENTURE OF A LIFETIME/ coldplay CHEAP THRILLS/ sia & sean paul AFTERGLOW/ ed sheeran CHEERLEADER/ omi AIN’T IT FUN/ paramore CIRCLES/ post malone AIRPLANES/ b.o.b w/haley williams CLASSIC/ mkto ALIVE/ krewella CLOSER/ chainsmokers ALL ABOUT THAT BASS/ meghan trainor CLUB CAN’T HANDLE ME/ flo rida ALL ABOUT THAT BASS/ postmodern jukebox COME GET IT BAE/ pharrell williams ALL I NEED/ awol nation COOLER THAN ME/ mike posner ALL I ASK/ adele COOL KIDS/ echosmith ALL OF ME/ john legend COUNTING STARS/ one republic ALL THE WAY/ timeflies CRAZY/ kat dahlia ALWAYS REMEMBER US THIS WAY/ lady gaga CRUISE REMIX/ florida georgia line & nelly A MILLION DREAMS/ greatest showman DANGEROUS/ guetta & martin AM I WRONG/ nico & vinz DAYLIGHT/ maroon 5 ANIMALS/ maroon 5 DEAR FUTURE HUSBAND/ meghan trainor ANYONE/ justin bieber DELICATE/ taylor swift APPLAUSE/ lady gaga DIAMONDS/ sam smith A THOUSAND YEARS/ christina perri DIE WITH YOU/ beyonce BABY/ justin bieber DIE YOUNG/ kesha BAD BLOOD/ taylor swift DOMINO/ jessie j BAD GUY/ billie eilish DON’T LET ME DOWN/ chainsmokers BANG BANG/ jessie j and ariana grande DON’T START NOW/ dua lipa BEFORE I LET GO/ beyonce DON’T STOP THE PARTY/ pitbull BENEATH YOUR BEAUTIFUL/ labrinth DRINK YOU AWAY/ justin timberlake BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE/ chris brown DRIVE BY/ train BEST DAY OF MY LIFE/ american authors DRIVERS LICENSE/ olivia rodrigo BEST SONG EVER/ one direction -

The Totally 80S Karaoke Song List! Alpha by Artist

The Totally 80s Karaoke Song List! Alpha by Artist Disc # Artist Song J 89 10000 Maniacs Like The Weather D 229 38Special Hold On Loosely H 229 A Ha Take On Me H 645 Abba Super Trouper A 520 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long D 198 AC/DC Back In Black D 188 AC/DC Hells Bells H 38 Adam Ant Goody Two Shoes F2 1 Aerosmith Dude Looks Like a Lady F2 2 Aerosmith Love in an Elevator D 967 Aerosmith Walk This Way H 315 Air Supply All Out Of Love H 1124 Air Supply Lost In Love A 41 Alabama Mountain Music G 744 Alan Jackson Here In The Real World A 130 AlannahMyles Black Velvet D 118 Alice Cooper Generation Landslide D 777 AlJarreau After All H 1024 Amy Grant El Shaddai H 1000 Amy Grant / Peter Cetera Next Time I Fall H 1165 Anita Baker Caught Up In The Rapture A 652 AnitaBaker Sweet Love G 1076 Atlantic Star Always H 251 Atlantic Star Secret Lovers B 126 Atlantic Starr Always H 1200 Atlantic Starr Masterpiece H 245 B. Segar / Silver Bul. Against The Wind D 1179 B52's Love Shack H 185 B-52's Roam H 254 Bad English When I See You Smile A 337 Bananarama Venus H 187 Bananarama Cruel Summer D 902 Bangles Eternal Flame D 1201 Bangles Manic Monday A 339 Bangles Walk Like An Egyptian D 1139 Barbra Streisand Memory D 1106 Barbra Streisand People J 76 Barbra Streisand/Barry GibbGuilty H 282 Berlin Take My Breath Away G 714 Bertie Higgins Just Another Day In Paradise D 1067 Bette Midler Wind Beneath My Wings, The A 561 Billy Idol Cradle Of Love E2 15 Billy Idol Rebel Yell H 1228 Billy Idol White Wedding A 336 Billy Joel It's Still Rock And Roll To Me A 321