Robert Hart's Encounter With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF Catalogue

Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers 46, Great Russell Street Telephone: 020 7631 4220 (opp. British Museum) Fax: 020 7631 1882 Bloomsbury, Email: [email protected] London www.jarndyce.co.uk WC1B 3PA VAT.No.: GB 524 0890 57 CATALOGUE CCXXVIII WINTER 2017-2018 THE MUSEUM Catalogue: Ed Nassau Lake. Production: Carol Murphy & Ed Nassau Lake. All items are London-published and in at least good condition, unless otherwise stated. Prices are nett. Items marked with a dagger (†) incur VAT (20%) to customers within the EU. A charge for postage and insurance will be added to the invoice total. We accept payment by VISA or MASTERCARD. If payment is made by US cheque, please add $25.00 towards the costs of conversion. Images of all items are available on the Current Catalogues page at www.jarndyce.co.uk JARNDYCE CATALOGUES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE, price £10.00 each, include: Books & Pamphlets 1641-1825; Sex, Drugs & Popular Medicine; Women Writers, Part I: A-F; European Literature in Translation; Bloods & Penny Dreadfuls; The Dickens Catalogue; Conduct & Education; Anthony Trollope, A Bicentenary Catalogue. The Romantics: A-Z, with The Romantic Background (four catalogues); JARNDYCE CATALOGUES IN PREPARATION include: 19th Century Novels; Women Writers (Part II: G-O); Plays; Turn of the Century, 1890-1920; English Language. PLEASE REMEMBER: If you have books to sell, please get in touch with Brian Lake at Jarndyce. Valuations for insurance or probate can be undertaken anywhere, by arrangement. A SUBSCRIPTION SERVICE is available for Jarndyce Catalogues for those who do not regularly purchase. Please send £30.00 (£60.00 overseas) for four issues, specifying the catalogues you would like to receive. -

Miscellaneous Manuscripts Collection, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf829008pt No online items Miscellaneous manuscripts collection, ca. 1750- LSC.0100 UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé and edited by Josh Fiala. UCLA Library Special Collections Finding aid last modified on 13 November 2019. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Miscellaneous manuscripts LSC.0100 1 collection, ca. 1750- LSC.0100 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Miscellaneous manuscripts collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.0100 Physical Description: 136.5 Linear Feet(261 boxes, 6 cartons, and 20 oversize boxes) Date: circa 1750- Stored off-site at SRLF. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance through our electronic paging system using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Portions of collection unprocessed. Boxes 204-280 are unavailable for access. Please contact Special Collections reference ([email protected]) for more information. Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Miscellaneous manuscripts collection (Collection 100). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. -

Thackeray's Qualifications As a Literary Critic

CHAPTER I Thackeray's Qualifications as a Literary Critic I. Thackeray's first qualification for literary criticism was the "aesthetic edu cation" which he underwent rather outside the walls of school and university huildings than inside them and which eventually proved more rewarding than the school and university curricula, although his formal education, being good, even though unfinished, does of course form a very important part of his endowment. This informal and voluntary aesthetic education had many aspects, the chief of them being the discussions on art and literature which he carried on with his school and later his University friends, his extensive reading, both his regular and his voluntary study of the art of painting in the Paris and London studios, museums and galleries, his visits to theatres and concerts, and his own early activities as writer, critic and caricaturist. One of the most important assets for him as literary critic was of course his extensive knowledge of literature, especially of those genres which later became the main subject of his critical interest (fiction, historical, biographical and travel-books), but also of those to which he paid, as critic, lesser attention (poetry and drama). We possess much direct evidence concerning his familiarity with the works of a very great number of classical, English, French, German, Italian and American writers, supplied by the records of his reading in his diaries, by the state of his library, the testimony of his friends, the records of his conversations, numerous occasional references to individual books and writers in his works and correspondence, and of course the bibliography of his criticism. -

Plays Licensed in 1854

52945 A - HH. LORD CHAMBERLAIN'S PLAYS, 1852 - 1866. January - March 1854. A. César Birotteau, ‘drame-vaudeville’ in three acts by ‘MM. Lagrangé et Cormon’ (i.e. H. F. Cardailhac and P. E. Piestre). Printed. French. Licence sent 9 January 1854 for performance at the Soho Theatre. Original first performance at Théâtre du Panthéon 4 April 1838. Signed by Armand Villot. Passages handwritten for later addition bound with original MS. LCO Day Book Add. 53073 records the stipulation that lines containing the phrase 'le dimanche est aboli' be omitted. Keywords: fashion, French influence, Paris, family relationships, businessmen. ff. 28. B. ‘Eustache', drama in three acts by John Courtney. Licence sent 9 January 1854 for performance at the Surrey. Songs included in MS. Published in Lacy's, vol. 15, no. 224, as Eustache Baudin. Keywords: land and farming, French influence, military, food and dining, orphans, servants, fashion, abandonment, family relationships, death, crime, execution, murder. ff. 54. C. 'Gin and water, or, The times we live in', drama in three acts. Licence sent 11 January for performance at the Victoria 16 January 1854. Request for licence written and signed by Eliza Vincent. Songs included in MS. For other versions, see Add. 52945 V and 52945 W. Keywords: drinking and drunkenness, food and dining, poverty, children, natural phenomena, working class characters, prisons and prisoners, family relationships, urban-rural contrast. ff. 36. D. 'A struggle for gold, or, A mother's prayer and the adventurer of Mexico', drama in five acts by Edward Stirling. Licence sent 16 January for performance at the City of London 23 January 1854. -

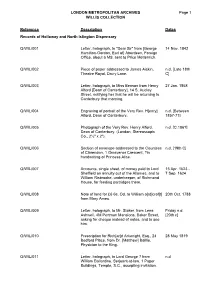

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES WILLIS COLLECTION Q/WIL Page 1 Reference Description Dates Records of Holloway and North Islington

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 WILLIS COLLECTION Q/WIL Reference Description Dates Records of Holloway and North Islington Dispensary Q/WIL/001 Letter, holograph, to "Dear Sir" from [George 14 Nov. 1842 Hamilton-Gordon, Earl of] Aberdeen, Foreign Office, about a MS. sent to Price Metternich. Q/WIL/002 Piece of paper addressed to James Aickin, n.d. [Late 18th Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. C] Q/WIL/003 Letter, holograph, to Miss Benson from Henry 27 Jan. 1858 Alford [Dean of Canterbury], 14 S. Audley Street, notifying her that he will be returning to Canterbury that morning. Q/WIL/004 Engraving of portrait of the Very Rev. H[enry] n.d. [Between Alford, Dean of Canterbury. 1857-71] Q/WIL/005 Photograph of the Very Rev. Henry Alford, n.d. [C.186?] Dean of Canterbury. (London, Stereoscopic Co., 2½" x 2"). Q/WIL/006 Section of envelope addressed to the Countess n.d. [19th C] of Clarendon, 1 Grosvenor Crescent, ?in handwriting of Princess Alice. Q/WIL/007 Accounts, single sheet, of money paid to Lord 15 Apr. 1623 - Sheffield on annuity out of the Allomes, and to 7 Sep. 1624 William Risbrooke, underkeeper, of Richmond House, for feeding partridges there. Q/WIL/008 Note of land for £6 6s. Od. to William o[rd]crof[t] 20th Oct. 1788 from Mary Ames. Q/WIL/009 Letter, holograph, to Mr. Stoker, from Lena Friday n.d. Ashwell, 4M Portman Mansions, Baker Street, [20th c] asking for cheque instead of notes, and to see him. Q/WIL/010 Prescription for Rich[ar]d Arkwright, Esq., 24 28 May 1819 Bedford Place, from Dr.