“In All Truthfulness As I Remember It”: Deciphering Myth And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 13: Settling the West, 1865-1900

The Birth of Modern America 1865–1900 hy It Matters Following the turmoil of the Civil War and W Reconstruction, the United States began its transformation from a rural nation to an indus- trial, urban nation. This change spurred the growth of cities, the development of big busi- ness, and the rise of new technologies such as the railroads. New social pressures, including increased immigration, unionization move- ments, and the Populist movement in politics, characterized the period as well. Understanding this turbulent time will help you understand similar pressures that exist in your life today. The following resources offer more information about this period in American history. Primary Sources Library See pages 1052–1053 for primary source Coat and goggles worn in a readings to accompany Unit 5. horseless carriage Use the American History Primary Source Document Library CD-ROM to find additional primary sources about the begin- nings of the modern United States. Chicago street scene in 1900 410 “The city is the nerve center of our civilization. It is also the storm center.” —Josiah Strong, 1885 Settling the West 1865–1900 Why It Matters After the Civil War, a dynamic period in American history opened—the settlement of the West. The lives of Western miners, farmers, and ranchers were often filled with great hardships, but the wave of American settlers continued. Railroads hastened this migration. During this period, many Native Americans lost their homelands and their way of life. The Impact Today Developments of this period are still evident today. • Native American reservations still exist in the United States. -

2015 23Rd Annual Poets House Showcase Exhibition Catalog

2015 23rd Annual Poets House Showcase Exhibition Catalog |Poets House|10 River Terrace|New York, NY 10282|poetshouse.org| 5 The 2015 Poets House Showcase is made possible through the generosity of the hundreds of publishers and authors who have graciously donated their works. We are deeply grateful to Deborah Saltonstall Pease (1943 – 2014) for her foundational support. Many thanks are also due to the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs, the Leon Levy Foundation, and the many members of Poets House for their support of this project. 6 I believe that poetry is an action in which there enter as equal partners solitude and solidarity, emotion and action, the nearness to oneself, the nearness to mankind and to the secret manifestations of nature. – Pablo Neruda Towards the Splendid City Nobel Lecture, 1971 WELCOME to the 2015 Poets House Showcase! Each summer at Poets House, we celebrate all of the poetry published in the previous year in an all-inclusive exhibition and festival of readings from new work. In this year’s Showcase, we are very proud to present over 3,000 poetry books, chapbooks, broadsides, artist’s books, and multimedia projects, which represent the work of over 700 publishers, from commercial publishers to micropresses, both domestic and foreign. For twenty-three years, the annual Showcase has provided foundational support for our 60,000-volume library by helping us keep our collection current and relevant. With each Showcase, Poets House—one of the most extensive poetry collections in the nation—continues to build this comprehensive poetry record of our time. -

American Heritage Day

American Heritage Day DEAR PARENTS, Each year the elementary school students at Valley Christian Academy prepare a speech depicting the life of a great American man or woman. The speech is written in the first person and should include the character’s birth, death, and major accomplishments. Parents should feel free to help their children write these speeches. A good way to write the speech is to find a child’s biography and follow the story line as you construct the speech. This will make for a more interesting speech rather than a mere recitation of facts from the encyclopedia. Students will be awarded extra points for including spiritual application in their speeches. Please adhere to the following time limits. K-1 Speeches must be 1-3 minutes in length with a minimum of 175 words. 2-3 Speeches must be 2-5 minutes in length with a minimum of 350 words. 4-6 Speeches must be 3-10 minutes in length with a minimum of 525 words. Students will give their speeches in class. They should be sure to have their speeches memorized well enough so they do not need any prompts. Please be aware that students who need frequent prompting will receive a low grade. Also, any student with a speech that doesn’t meet the minimum requirement will receive a “D” or “F.” Students must portray a different character each year. One of the goals of this assignment is to help our children learn about different men and women who have made America great. Help your child choose characters from whom they can learn much. -

NATIONAL COWBOY POETRY GATHERING January 27–February 1, 2020 · Elko, Nevada

Ocial Program , 2013 Trail Blazers Trail Marion Coleman, THE WESTERN FOLKLIFE CENTER presents THE 36TH NATIONAL COWBOY POETRY GATHERING January 27–February 1, 2020 · Elko, Nevada 36TH NATIONAL COWBOY POETRY GATHERING 1 Hear something thoughtful or get some inspiration? Write it down! Meet someone cool? Get their autograph! Donors, Sponsors, and Partners Thank You to Our Major Sponsors » The Ford Foundation » McMullen, McPhee & Co. LLC » William Randolph Hearst Foundation » John Muraglia » E. L. Wiegand Foundation » Jesselie & Scott Anderson » Elko Recreation Board » Reed & Mary Simmons » City of Elko » Sally Searle » NV Energy » Blach Distributing » Nevada Gold Mines » Elko Convention and Visitors Authority » Laura & E.W. Littlefield, Jr. » Red Lion Hotel & Casino » Nevada Arts Council » Stockmen’s Casino & Ramada Hotel » National Endowment for the Arts » Joel & Kim Laub $10,000 and up as of 12/16/19 Thank You to Our National Cowboy Poetry Gathering Sponsors and Partners » Nevada Humanities/National » C-A-L Ranch Endowment for the Humanities » Marigold Mine » Tito & Sandra Tiberti » Coach USA » The Martin Guitar Charitable Foundation » Townplace Suites by Marriott » Anna Ball » Morgan Stanley » KNPB Channel 5 Public Broadcasting » Picture This » Nevada Division of Tourism/TravelNevada » Wrangler » Best Western Elko Inn » Star Hotel » Ledgestone Hotel » Nevada Health Centers » Home2Home » Northeastern Nevada Regional Hospital » Wingate by Wyndham Elko » Great Basin Beverage » Holiday Inn & Suites » Northeastern Nevada Stewardship Group -

ED439719.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 439 719 IR 057 813 AUTHOR McCleary, Linda C., Ed. TITLE Read from Sea to Shining Sea. Arizona Reading Program. Program Manual. INSTITUTION Arizona Humanities Council, Phoenix.; Arizona State Dept. of Library, Archives and Public Records, Phoenix. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 414p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cooperative Programs; Games; Learning Activities; *Library Planning; Library Services; *Reading Motivation; *Reading Programs; State Programs; Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS *Arizona ABSTRACT This year is the first for the collaborative effort between the Arizona Department of Library, Archives and Public Records, and Arizona Humanities Council and the members of the Arizona Reads Committee. This Arizona Reading Program manual contains information on program planning and development, along with crafts, activity sheets, fingerplays, songs, games and puzzles, and bibliographies grouped in age specific sections for preschool children through young adults, including a section for those with special needs. The manual is divided into the following sections: Introductory Materials; Goals, Objectives and Evaluation; Getting Started; Common Program Structures; Planning Timeline; Publicity and Promotion; Awards and Incentives; Parents/Family Involvement; Programs for Preschoolers; Programs for School Age Children; Programs for Young Adults; Special Needs; Selected Bibliography; Resources; Resource People; and Miscellaneous materials.(AEF) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. rn C21 Read from Sea to Shining Sea Arizona Reading Program Program Manual By Linda C. McCleary, Ed. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND Office of Educational Research and Improvement DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION BEEN GRANTED BY CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization Ann-Mary Johnson originating it. -

06 21 2016 (Pdf)

6-21-16 sect. 1.qxp:Layout 1 6/16/16 11:56 AM Page 1 Grandin emphasizes stockmanship at 5th International Symposium on Beef Cattle Welfare By Donna Sullivan, Editor and they all had the lower worse.” The one message that Dr. hair whorls. Cattle overall Grandin emphasized that Temple Grandin has champi- are getting calmer.” an animal’s first experience oned throughout her career is But she cautioned against with a new person, place or that stockmanship matters. over-emphasizing tempera- piece of equipment needs to And the world-renowned ment. “We don’t want to turn be a good one. “New things Colorado State University beef cattle into a bunch of are scary when you shove professor and livestock han- Holsteins,” she warned. them in their face,” she said. dling expert didn’t vary from “That would probably be a “But they are attractive when that theme as she presented really bad idea because we they voluntarily approach. A at the 5th International Sym- want a cow that’s going to basic principle is that when posium on Beef Cattle Wel- defend her calf.” you force animals to do fare hosted by Kansas State She also pointed out that something, you’re going to University’s Beef Cattle In- temperament scores can be get a lot more fear stress than stitute in early June. She pre- changed with experience, by when they voluntarily go sented a great deal of re- acclimating cattle to new through the facility.” search illustrating the corre- people and experiences. Un- Grandin said she has seen lation between how cattle are fortunately, people don’t al- an improvement in people’s handled and their overall ways want to take the time attitudes towards animals performance. -

Handout - Excerpt from Life and Adventures of Nat Love Nat Love Was Born Into Slavery in 1854 in Davidson, Tennessee

Handout - Excerpt from Life and Adventures of Nat Love Nat Love was born into slavery in 1854 in Davidson, Tennessee. After the Civil War, he was released from slavery and worked on a family farm before moving to Dodge City, Kansas, to become a cowboy. Love’s time driving cattle made him into a folk legend, and he became known as “Deadwood Dick.” The following excerpt comes from Chapter 6 of Love’s memoir, entitled Life and Adventures of Nat Love. We were compelled to finish our journey home almost on foot, as there were only six horses left to fourteen of us. Our friend and companion who was shot in the fight, we buried on the plains, wrapped in his blanket with stones piled over his grave. After this engagement with the Indians I seemed to lose all sense as to what fear was and thereafter during my whole life on the range I never experienced the least feeling of fear, no matter how trying the ordeal or how desperate my position. The home ranch was located on the Palo Duro river in the western part of the Pan Handle, Texas, which we reached in the latter part of May, it taking us considerably over a month Nat Love to make the return journey home from Dodge City. I remained in the employ of the Duval outfit for three years, making regular trips to Dodge City every season and to many other places in the surrounding states with herds of horses and cattle for market and to be delivered to other ranch owners all over Texas, Wyoming and the Dakotas. -

Nat Love 1854 – 1921 Story: R. Alan Brooks Art: Cody Kuehl Discussion Questions: 3-5Th Grade

Nat Love 1854 – 1921 Story: R. Alan Brooks Art: Cody Kuehl Discussion Questions: 3-5th Grade • When you think of a cowboy, what do you see in your mind? What do they wear? What do they do with their day? • What do you want to be when you grow up? What would you do if someone told you that you are not allowed to do that? • Why did the members of the Pima Tribe let Nat go when they caught him? What does it mean to have respect for another person? • How does the comic make Nat’s experiences come to life? Which pictures show him engaging in an exciting activity? MS • Nat Love was born a slave and, as such, was not allowed to learn to read. Why do you suppose that law existed? • In the second panel of the first page, Nat says “a lot of folks dispute the facts of my life, saying it’s all too incredible to be true.” Are there any parts of this story that you find hard to believe? • Nat Love took the name “Deadwood Dick.” What would your cowboy name be if you could choose it for yourself? • In both the fifth panel of the first page and the second panel of the second page, Nat is shown firing his gun from horseback. How does including two images that are so similar to one another enhance your understanding of the character? HS • The artwork of this comic contains a lot of thick lines and an abundance of deep shading. How does this style inform the tone of the story being told here? • Why do you suppose that people today do not believe, as Nat points out in the comic, that there were any African American cowboys? • Not only was Nat literate, he wrote a book about his life. -

American Folklife Center & Veterans History Project

AMERICAN FOLKLIFE CENTER & VETERANS HISTORY PROJECT Library of Congress Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2010 (October 2009-September 2010) The American Folklife Center (AFC), which includes the Veterans History Project (VHP), had another productive year. Over 150,000 items were acquired, and over 127,000 items were processed by AFC's archive, which is the country’s first national archive of traditional culture, and one of the oldest and largest of such repositories in the world. VHP continued making strides in its mission to collect and preserve the stories of our nation's veterans, acquiring 7,408 collections (13,744 items) in FY2010. The VHP public database provided access to information on all processed collections; its fully digitized collections, whose materials are available through the Library’s web site to any computer with internet access, now number over 8,000. Together, AFC and VHP acquired a total of 168,198 items in FY2010, of which 151,230 were Non-Purchase Items by Gift. AFC and VHP processed a total of 279,298 items in FY2010, and cataloged 54,758 items. AFC and VHP attracted just under five million “Page Views” on the Library of Congress website, not counting AFC’s popular “American Memory” collections. ARCHIVAL ACCOMPLISHMENTS KEY ACQUISITIONS American Voices with Senator Bill Bradley (AFC 2010/004) 117 born-digital audio recordings of interviews from the radio show American Voices, hosted by Sen. Bill Bradley (also appearing under the title American Voices with Senator Bill Bradley), produced by Devorah Klahr for Sirius XM Satellite Radio, Washington, D.C. Dyann Arthur and Rick Arthur Collection of MusicBox Project Materials (AFC 2010/029) Over 100 hours of audio and video interviews of women working as roots musicians and/or singers. -

Shorty's Yarns: Western Stories and Poems of Bruce Kiskaddon

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2004 Shorty's Yarns: Western Stories and Poems of Bruce Kiskaddon Bruce Kiskaddon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Kiskaddon, B., Field, K., & Siems, B. (2004). Shorty's yarns: Western stories and poems of Bruce Kiskaddon. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHORTY’S YARNS Western Stories and Poems of Bruce Kiskaddon Illustrations by Katherine Field Edited and with an introduction by Bill Siems Shorty’s Yarns THE LONG HORN SPEAKS The old long horn looked at the prize winning steer And grumbled, “What sort of a thing is this here? He ain’t got no laigs and his body is big, I sort of suspicion he’s crossed with a pig. Now, me! I can run, I can gore, I can kick, But that feller’s too clumsy for all them tricks. They’re breedin’ sech critters and callin’ ‘em Steers! Why the horns that he’s got ain’t as long as my ears. I cain’t figger what he’d have done in my day. They wouldn’t have stuffed me with grain and with hay; Nor have polished my horns and have fixed up my hoofs, And slept me on beddin’ in under the roofs Who’d have curried his hide and have fuzzed up his tail? Not none of them riders that drove the long trail. -

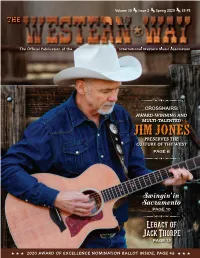

Spring 2020 $5.95 THE

Volume 30 Issue 2 Spring 2020 $5.95 THE The Offi cial Publication of the International Western Music Association CROSSHAIRS: AWARD-WINNING AND MULTI-TALENTED JIM JONES PRESERVES THE CULTURE OF THE WEST PAGE 6 Swingin’ in Sacramento PAGE 10 Legacy of Jack Thorpe PAGE 12 ★ ★ ★ 2020 AWARD OF EXCELLENCE NOMINATION BALLOT INSIDE, PAGE 46 ★ ★ ★ __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 1 3/18/20 7:32 PM __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 2 3/18/20 7:32 PM 2019 Instrumentalist of the Year Thank you IWMA for your love & support of my music! HaileySandoz.com 2020 WESTERN WRITERS OF AMERICA CONVENTION June 17-20, 2020 Rushmore Plaza Holiday Inn Rapid City, SD Tour to Spearfish and Deadwood PROGRAMMING ON LAKOTA CULTURE FEATURED SPEAKER Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve SESSIONS ON: Marketing, Editors and Agents, Fiction, Nonfiction, Old West Legends, Woman Suffrage and more. Visit www.westernwriters.org or contact wwa.moulton@gmail. for more info __WW Spring 2020_Interior.indd 1 3/18/20 7:26 PM FOUNDER Bill Wiley From The President... OFFICERS Robert Lorbeer, President Jerry Hall, Executive V.P. Robert’s Marvin O’Dell, V.P. Belinda Gail, Secretary Diana Raven, Treasurer Ramblings EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Marsha Short IWMA Board of Directors, herein after BOD, BOARD OF DIRECTORS meets several times each year; our Bylaws specify Richard Dollarhide that the BOD has to meet face to face for not less Juni Fisher Belinda Gail than 3 meetings each year. Jerry Hall The first meeting is usually in the late January/ Robert Lorbeer early February time frame, and this year we met Marvin O’Dell Robert Lorbeer Theresa O’Dell on February 4 and 5 in Sierra Vista, AZ. -

Nat Love's Autobiography, 1907

When I arrived the town was full of cowboys Life and Adventures of Nat Love from the surrounding ranches, and from Texas (Nat Love’s Autobiography, 1907) and other parts of the west. Kansas was a great Chapter 6 excerpt- Becoming a Cowboy cattle center and market, with many wild cowboys, prancing horses of which I was very fond, and the wild life generally. They all had It was on the tenth day of February, 1869, that I left the old home, near Nashville, their attractions for me, and I decided to try for a Tennessee. I was at that time about fifteen years place with them. Although it seemed to me I had old, and though while young in years the hard met with a bad outfit, at least some of them, I work and farm life had made me strong and watched my chances to get to speak with them. I hearty, much beyond my years, and I had full wanted to find someone whom I thought would confidence in myself as being able to take care of give me a civil answer to the questions I wanted myself and making my way. to ask, but they all seemed too wild around town, so the next day I went out where they I at once struck out for Kansas of which I had were in camp. heard something. And I believed it was a good Approaching a party who were eating their place in which to seek employment. It was in the breakfast, I got to speak with them.