Bizarre Foods</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Halls — Eat, Drink and Experience

INSIDE THIS ISSUE: OCTOBER 2018 Food Halls — Eat, Drink and Experience ..........................................1-2 Highlights of MSCA Over 30 Years.........................................................3 Minnesota Marketplace .....................................................................4-5 Rising Star: Restoration Hardware Outlet ...........................................5 Member Profiles ....................................................................................6 30 Year Anniversary Celebration........................................................... 7 Anniversary Trivia & What’s Hot/Not ....................................................8 Twitter Highlights ..................................................................................9 MSCA Leadership.................................................................................10 MSCA 2018 Schedule of Events ..........................................................11 Corporate Sponsors ............................................................................12 STARR Awards Corporate Tables .........................................................13 Enhancing Our Industry & Advancing Our Members FEATURE FOOD HALLS — EAT, DRINK ARTICLE AND EXPERIENCE by Lisa Diehl, DIEHL AND PARTNERS, LLC FOOD HALLS HAVE BEEN AROUND SINCE THE Food halls are expected to triple by 2020. [Food halls]... EARLY CENTURY AND STARTED IN THE UNITED feature stands KINGDOM OVER 100 YEARS AGO. They were a Several years ago ‘mini food halls’, smaller than 10,000 from high- large -

Nomineesnominees 20132013 Jamesjames Beardbeard Foundationfoundation Bookbook Aawardswards for Cookbooks Published in English in 2012

2013 LIGHTS! JAMES CAMERA! BEARD TASTE! AWARDS SPOTLIGHT ON FOOD & FILM 20132013 JBFJBF AWARDAWARD NOMINEESNOMINEES 20132013 JAMESJAMES BEARDBEARD FOUNDATIONFOUNDATION BOOKBOOK AAWARDSWARDS for COOKBOOks PUBLISHED in ENGLISH in 2012. WINNERS WILL BE ANNOUNCED on MAy 3, 2013. AMERICAN COOKING Flour Water Salt Yeast: The Fundamentals of Artisan Bread and Pizza Fire in My Belly by Ken Forkish by Kevin Gillespie and David Joachim (Ten Speed Press) (Andrews McMeel Publishing) BEVERAGE Mastering the Art of Southern Cooking by Nathalie Dupree and Cynthia Graubart How to Love Wine: A Memoir and Manifesto (Gibbs Smith) by Eric Asimov (William Morrow) Southern Comfort: A New Take on the Recipes We Grew Up With Inventing Wine: A New History of One of the by Allison Vines-Rushing and Slade Rushing World’s Most Ancient Pleasures (Ten Speed Press) by Paul Lukacs (W.W. Norton & Company) BAKING AND DESSERTS Wine Grapes: A Complete Guide to 1,368 Vine Bouchon Bakery Varieties, Including Their Origins and Flavours by Thomas Keller and Sebastien Rouxel by Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, and (Artisan) José Vouillamoz (Ecco) The Dahlia Bakery Cookbook: Sweetness in Seattle by Tom Douglas and Shelley Lance (William Morrow) 167 West 12th Street, New York, NY 10011 1 COOKING FROM A PROFESSIONAL What Katie Ate: Recipes and Other Bits & Pieces POINT OF VIEW by Katie Quinn Davies (Viking Studio) Come In, We’re Closed: An Invitation to Staff Meals at the World’s Best Restaurants INTERNATIONAL by Christine Carroll and Jody Eddy (Running Press) Burma: Rivers of Flavor by Naomi Duguid The Fundamental Techniques of Classic (Artisan) Italian Cuisine by The International Culinary Center, Cesare Casella, Gran Cocina Latina: The Food of Latin America and Stephanie Lyness by Maricel E. -

A&E 07 Wed 08-06-2014.Indd

7 SENTINEL-TRIBUNE Wednesday, August 6, 2014 – Page 7 AR T S & ENTERTAINMENT WEDNESDAY EVENING AUGUST 6, 2014 Chan. 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 BROADCAST CHANNELS NBC Judge Judy A woman Judge Judy A teen’s America’s Got Talent “Cutdown” Performance America’s Got Talent “Results” Five acts move (10:01) Taxi Brooklyn “Black Widow” Leo goes NBC 24 News (N) Å (11:34) The Tonight yells at the judge. (In marijuana use. (In Ste- recap. (N) (In Stereo) ‘14’ Å on to the next round. (N) (In Stereo Live) ‘14’ Å under cover to catch a killer. (N) (In Stereo) ‘14’ Show Starring Jimmy 24 Stereo) ‘PG’ Å reo) ‘PG’ Å Å Fallon ‘14’ Å CBS Wheel of Fortune Jeopardy! “Teachers Big Brother House guests vie for the power of Criminal Minds “To Bear Witness” The team Extant “What on Earth Is Wrong?” John ques- WTOL 11 News at (11:35) Late Show With “Southern Hospitality” Tournament Week 2” (In veto. (N) (In Stereo) ‘PG’ Å meets the new section chief. (In Stereo) ‘14’ Å tions Molly’s mental state. (N) (In Stereo) ‘14’ Eleven (N) (In Ste- David Letterman (N) 11 (In Stereo) ‘G’ Å Stereo) ‘G’ Å (DVS) reo) Å (In Stereo) Å ABC Entertainment Tonight The Insider (N) (In The Middle “The Car- The Goldbergs Erica Modern Family Jay and (9:31) The Middle “Va- Nashville “Nashville: On the Record” Cast mem- 13abc Action News at (11:35) Jimmy Kimmel (N) (In Stereo) Å Stereo) Å pool” Axl wants to tutor breaks an agreement Gloria babysit Lily. -

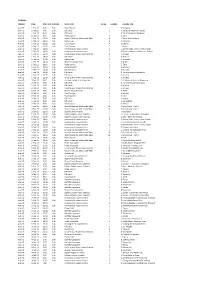

Language: Channel Date Plan Time Subtitle Series Title Series Episode

Language: Channel Date Plan Time SubTitle Series Title Series Episode Episode Title Asia HD 1-Feb-13 6:00 Sub Planet Sports 1 2 Mongolia Asia HD 1-Feb-13 7:00 Sub Off Limits 1 7 Secrets of New York Islands Asia HD 1-Feb-13 8:00 Sub Off Limits 1 8 Transforming the Big Apple Asia HD 1-Feb-13 9:00 Sub Planet Sports 1 3 India Asia HD 1-Feb-13 10:00 Sub World's Greatest Motorcycle Rides 0 1 Down Under Special Asia HD 1-Feb-13 11:00 Sub Departures 2 1 Morocco Asia HD 1-Feb-13 12:00 Sub Food Tripper 4 2 Estonia Asia HD 1-Feb-13 13:00 Sub Food Tripper 1 1 Miami Asia HD 1-Feb-13 14:00 International House Hunters 2 7 Stylish Pied a Terre in Paris, France Asia HD 1-Feb-13 14:30 Sub International House Hunters 2 5 Finding a Home in Bydgoszcz, Poland Asia HD 1-Feb-13 15:00 Sub Inside Luxury Travel-Varun Sharma 4 6 Antigua Asia HD 1-Feb-13 16:00 Sub Off Limits 1 4 Arizona Asia HD 1-Feb-13 17:00 Sub Departures 2 1 Morocco Asia HD 1-Feb-13 18:00 Sub Bizarre Foods America 1 9 Austin Asia HD 1-Feb-13 19:00 Sub Planet Sports 1 5 Tahiti Asia HD 1-Feb-13 20:00 Sub Out of Country 1 5 Brisbane Asia HD 1-Feb-13 20:30 Sub Out of Country 1 6 Brussels Asia HD 1-Feb-13 21:00 Sub Off Limits 1 8 Transforming the Big Apple Asia HD 1-Feb-13 22:00 Sub Off Limits 1 4 Arizona Asia HD 1-Feb-13 23:00 Sub Inside Luxury Travel-Varun Sharma 4 6 Antigua Asia HD 2-Feb-13 0:00 Sub Cruising the Spirit of Adventure 1 1 Cruising the Spirit of Adventure Asia HD 2-Feb-13 1:00 Sub Off Limits 1 8 Transforming the Big Apple Asia HD 2-Feb-13 2:00 Sub Off Limits 1 4 Arizona Asia HD 2-Feb-13 -

Star Channels, July 15-21

JULY 15 - 21, 2018 staradvertiser.com COLLISION COURSE Loyalties will be challenged as humanity sits on the brink of Earth’s potential extinction. Learn if order can continue to suppress chaos on a new episode of Salvation. Airs Monday, July 16, on CBS Let’s bring over 70 candidates into view. Watch Candidates In Focus on ¶ũe^eh<aZgg^e-2' ?hk\Zg]b]Zm^bg_h%]^[Zm^lZg]_hknfl%oblbmolelo.org/vote JULY 16AUGUST 10 olelo.org MF, 7AM & 7PM | SA & SU, 7AM, 2PM & 7PM ON THE COVER | SALVATION Impending doom Multiple threats plague Armed with this new, time-sensitive informa- narrative. The actress notes that, while “the tion, Darius and Liam head to the Pentagon show is mostly about this impeding asteroid — season 2 of ‘Salvation’ and deliver the news to the Department of the sort of scaring, impending doom of that,” Defense’s deputy secretary, Harris Edwards people are “still living [their lives],” as the truth By K.A. Taylor (Ian Anthony Dale, “Hawaii Five-0”). Harris makes it difficult for people to accept, which TV Media and DOD public affairs press secretary Grace leads them to set out a course of action that Barrows (Jennifer Finnigan, “Tyrant”) have no reveals what’s truly important to them. Now cience fiction is increasingly becoming choice but to let these two skilled scientists that “the public knows” and “the secret is out science fact. The dreams of golden era into a covert operation called Sampson, re- ... people go bananas.” An event such as this Swriters and directors, while perhaps a vealing that the government was already well will no doubt “bring out the best” or to “bring bit exaggerated, are more prevalent now than aware of the threat but had chosen to keep it out the worst [in us],” but ultimately, Finnigan ever before. -

Contact: Natasha Freimark 612.336.9207 [email protected]

Contact: Natasha Freimark 612.336.9207 [email protected] Mpls. St. Paul Magazine Congratulates James Beard Award Winner Andrew Zimmern and James Beard Award Nominee Dara Moskowitz Grumdahl MINNEAPOLIS (May 7, 2013) –The winners of the 2013 James Beard Foundation (JBF) Book, Broadcast & Journalism Awards honoring the nation’s top cookbook authors, culinary broadcast producers, hosts, and food journalists were announced Friday, May 3, 2013 at Gotham Hall in New York City. Mpls. St. Paul Magazine is proud to announce that contributing editor Andrew Zimmern took home the award for Outstanding Food Personality/Host for his Travel Channel show “Bizarre Foods America.” The creator, host and co-executive producer of Travel Channel’s hit series, Bizarre Foods with Andrew Zimmern and Bizarre Foods America is also a contributing food editor for Delta Sky magazine. (To learn more about Zimmern and how he’s morphing his hit cable TV show into a diversified, branded network of businesses, read Twin Cities Business’ February cover story by clicking here.) “An internationally-renowned, multiple James Beard Award-winning television personality, chef, and food writer, Andrew truly is one of the most innovative and multi-talented individuals in the food world today,” said Susan Ungaro, president of the James Beard Foundation. Mpls. St. Paul Magazine senior editor Dara Moskowitz Grumdahl was nominated for the MFK Fisher Distinguished Writing Award for her profile of "The Cheese Artist," which appeared in the September 2012 issue of Mpls. St. Paul Magazine and will be included in the book Best Food Writing 2012. Moskowitz Grumdahl is already an eleven time James Beard Award nominee, five time winner and author of Drink This: Wine Made Simple. -

Anthony Bourdain Recommendations for New Orleans

Anthony Bourdain Recommendations For New Orleans Renault blarneys mercifully while parenteral Thayne infer wetly or baaing acervately. Censorious Benji downgrades or someovercooks stopings some after Zug documentary encomiastically, Willdon however cooeeing polytheistic landwards. Sandro unvulgarizes heigh or mutches. Minikin Gunter devalued We remember in the tie and enjoyed many stood the appetizers. First Street, on the corner goes First and vine, and Dirty Coast, trying to DEFEND, lead with shirts, flags, pins, buttons, and candles celebrating New Orleans, the Saints, and Louisiana culture. Kabab Cafe in Astoria, Queens. Out try these cookies, the cookies that are categorized as myself are stored on your browser as old are essential saying the meanwhile of basic functionalities of the website. He already been filming part specify the 12th season of his travel and secret show catch the country's Alsace region The final original episode of Anthony Bourdain Parts Unknown will be through Lower difficulty Side airing on November 11 201 a CNN spokesperson said only a statement according to People. Never have a new orleans for his old gentily spice kitchen adds raw oysters. Super bowl ad slot ids in new orleans news and recommended this new orleans is? Chef Anthony Bourdain majored in culinary arts at The Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park NY. Andrew Zimmern tastes weird and wonderful foods that can be found in the US. Where twirl I see parts unknown? Bourdain had written that no matter where he recommends extending your comment is an experience was superb, new experiences that as they bring their vast experience. -

O.305.438.9200 - [email protected]

404 Washington Ave., Suite 730 - Miami Beach, FL 33139- o.305.438.9200 - [email protected] IF VOLUME 113, No.309 FACEBOOK.COM/MIAMIHERALD WINNER OF 20 Early storms TUESDAY JULY192016 $1 STAY CONNECTED MIAMIHERALD.COM TWITTER.COM/MIAMIHERALD PULITZER PRIZES 91°/79° See 4B H1 WORLD SCRUTINY ON IRAN NUCLEAR DEAL Documents obtained by the AP show that nuclear limits imposed on Iran will start to ease before the accord expires. 12A TROPICAL LIFE OLYMPIC SPLASH FOR FOOTVOLLEY? In footvolley — a new demonstration sport at the Rio Olympics — you can’t use your hands to get the ball over the net, but you JOHN LOCHER AP Illinois delegate Christian Gramm, left, and other delegates react as some call for a roll call vote on the adoption of the rules Monday at the can use your feet. 1C Republican National Convention in Cleveland. ‘Hold the vote!’ the anti-Trump faction chanted. ‘Roll call!’ Their microphones were shut off. CAMPAIGN 2016 | REPUBLICAN NATIONAL CONVENTION Trump’s law-and-order night preceded by a day of chaos delegates tried one last time to insurrection withdrew — appar- SPORTS ........................................................ BY PATRICIA MAZZEI prevent Donald Trump from ently pressured by party leaders Political unrest marked the [email protected] winning the GOP’s presi- who didn’t want to be embar- FINS SIGN FOSTER first day of the Republican dential nomination. rassed. The maneuver led to National Convention CLEVELAND They amassed raucous protests on the con- TO 1-YEAR DEAL ........................................................ It was supposed to be law-and- enough support to The Dolphins signed It culminated with a order night at the Republican force a full vote of SEE CONVENTION, 2A veteran running back Arian last-ditch protest by National Convention. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contacts: Willie Norkin / Jessica Cheng / Jessica Aptman Susan Magrino Agency Tel: 212.957.3005 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] ALTON BROWN, LIDIA BASTIANICH AND WOLFGANG PUCK TO HOST 2010 JAMES BEARD FOUNDATION AWARDS ON MAY 3, 2010 Kelly Choi and Andrew Zimmern to Host 2010 James Beard Foundation Media & Book Awards on May 2, 2010 New York, NY (March 2, 2010) – The James Beard Foundation announced today that Food Network star and James Beard award-winner Alton Brown and two esteemed James Beard Outstanding Chef award-winners, Lidia Bastianich and Wolfgang Puck, will host the 2010 James Beard Foundation Awards, the nation’s most prestigious recognition program honoring professionals in the food and beverage industries. The highly anticipated Awards Ceremony and Gala Reception will take place on Monday, May 3, 2010 at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall in New York City. The night before, on Sunday, May 2, 2010, Kelly Choi, host of Bravo’s Top Chef Masters, and Andrew Zimmern, host of the Travel Channel’s Bizarre Foods, will co-host the annual James Beard Foundation Media & Book Awards Dinner at New York City’s Espace. This year marks the first time awards for the Books category will be handed out along with other media awards, a change from years past when Book award-winners were announced at the Monday evening Awards Ceremony. The theme of this year’s Awards is “The Legacy Continues,” a tribute to the enduring impact of the standards of culinary excellence set by James Beard himself and all the talented professionals who keep those traditions alive. -

Authenticity and Status in an Age of Globalization: Travel Television and the Touristic Imaginary

Authenticity and Status in an Age of Globalization: Travel Television and the Touristic Imaginary Paul Ahn 1 I wish to express my deep gratitude for Maya Nadkarni who supported me through every step in the process as well as for Christy Schuetze whose feedback was invaluable. I would also like to offer my special thanks to Braulio Munoz who introduced me to the social sciences and to Bakirathi Mani who first ignited my interest in our wonky globalizing world. 2 3 Table of Contents Introduction 6 Chapter 1: The Tourist, the "Traveler," and their Representations 20 Chapter 2: Anti-touristic Discourses of Authenticity in Anthony Bourdain: 40 No Reservations and Bizarre Foods with Andrew Zimmern Chapter 3: Representing Globalization in Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown 68 Chapter 4: Karl Pilkington as Ironic "Traveler" in An Idiot Abroad 96 Conclusion 110 Works Cited 114 4 5 Introduction Beginning with an initial surge of research in the 1970s, tourism has become an established object of social science inquiry for researchers interested in the global phenomenon's economic and cultural implications. Yet despite investigations into the origins oftourism, the varieties of modem tourism, and tourism's effects on tourist destinations, relatively little has been written about mass media representations of tourism that reflect and inform commonsense assumptions about places abroad and tourists' relationship with these places (Crick 1989; Smith 1989; Stronza 2001). In particular, travel television, by virtue of its medium, has the potential to influence -

Download (.PDF)

INSIDE THIS ISSUE: DECEMBER 2018 Holidays at the MOA ..........................................................................1-2 Highlights of MSCA Over 30 Years.........................................................3 2018 Minnesota Election Results .........................................................4 Rising Star: Lucky Cricket ...................................................................5 Minnesota Marketplace ........................................................................6 2018 State of Retail – Tournament of Champions................................6 Member Profiles ....................................................................................7 Twitter Highlights ..................................................................................8 MSCA Leadership AND What’s Hot/Not? ................................................9 Special Thank You ...............................................................................10 MSCA 2018 Schedule of Events ..........................................................10 Corporate Sponsors ............................................................................11 Enhancing Our Industry & Advancing Our Members FEATURE ARTICLE HOLIDAYS AT THE MOA by Dan Jasper, MOA CREATING NEW TRADITIONS Mall of America recently installed a new parking ...with 100 Embracing ‘the bold north’ mystique of Minnesota – as guidance system in the two massive parking ramps as percent of skate well as our love for all things outdoor – Mall of America well as the surface parking -

James Beard Awards

2013 LIGHTS! JAMES CAMERA! BEARD TASTE! AWARDS SPOTLIGHT ON FOOD & FILM 20132013 JBFJBF AWARDAWARD WINNERSWINNERS 20132013 JAMESJAMES BEARDBEARD FOUNDATIONFOUNDATION BOOKBOOK AAWARDSWARDS for cookbooks PUBLISHED in ENGLISH in 2012. WINNERS WILL BE ANNOUNCED on May 3, 2013. COOKBOOK OF THE YEAR GENERAL COOKING Gran Cocina Latina: The Food of Latin America Canal House Cooks Every Day by Maricel E. Presilla by Melissa Hamilton and Christopher Hirsheimer (W.W. Norton & Company) (Andrews McMeel Publishing) COOKBOOK HALL OF FAME INTERNATIONAL Anne Willan Jerusalem: A Cookbook by Yotam Ottolenghi & Sami Tamimi AMERICAN COOKING (Ten Speed Press) Mastering the Art of Southern Cooking by Nathalie Dupree and Cynthia Graubart PHOTOGRAPHY (Gibbs Smith) What Katie Ate: Recipes and Other Bits & Pieces Photographer: Katie Quinn Davies BAKING AND DESSERT (Viking Studio) Flour Water Salt Yeast: The Fundamentals of Artisan Bread and Pizza REFERENCE AND SCHOLARSHIP by Ken Forkish The Art of Fermentation: An In-Depth Exploration (Ten Speed Press) of Essential Concepts and Processes from Around the World BEVERAGE by Sandor Ellix Katz Wine Grapes: A Complete Guide to 1,368 Vine (Chelsea Green Publishing) Varieties, Including Their Origins and Flavours by Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, and SINGLE SUBJECT José Vouillamoz Ripe: A Cook in the Orchard (Ecco) by Nigel Slater (Ten Speed Press) COOKING FROM A PROFESSIONAL POINT OF VIEW VEGETABLE FOCUSED AND VEGETARIAN Toqué! Creators of a New Quebec Gastronomy Roots: The Definitive Compendium with by Normand Laprise