Arxiv:0810.4637V4 [Physics.Class-Ph]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Basic Set-Up 2 Poisson Brackets

MATHEMATICS 7302 (Analytical Dynamics) YEAR 2016–2017, TERM 2 HANDOUT #12: THE HAMILTONIAN APPROACH TO MECHANICS These notes are intended to be read as a supplement to the handout from Gregory, Classical Mechanics, Chapter 14. 1 The basic set-up I assume that you have already studied Gregory, Sections 14.1–14.4. The following is intended only as a succinct summary. We are considering a system whose equations of motion are written in Hamiltonian form. This means that: 1. The phase space of the system is parametrized by canonical coordinates q =(q1,...,qn) and p =(p1,...,pn). 2. We are given a Hamiltonian function H(q, p, t). 3. The dynamics of the system is given by Hamilton’s equations of motion ∂H q˙i = (1a) ∂pi ∂H p˙i = − (1b) ∂qi for i =1,...,n. In these notes we will consider some deeper aspects of Hamiltonian dynamics. 2 Poisson brackets Let us start by considering an arbitrary function f(q, p, t). Then its time evolution is given by n df ∂f ∂f ∂f = q˙ + p˙ + (2a) dt ∂q i ∂p i ∂t i=1 i i X n ∂f ∂H ∂f ∂H ∂f = − + (2b) ∂q ∂p ∂p ∂q ∂t i=1 i i i i X 1 where the first equality used the definition of total time derivative together with the chain rule, and the second equality used Hamilton’s equations of motion. The formula (2b) suggests that we make a more general definition. Let f(q, p, t) and g(q, p, t) be any two functions; we then define their Poisson bracket {f,g} to be n def ∂f ∂g ∂f ∂g {f,g} = − . -

Hamilton Description of Plasmas and Other Models of Matter: Structure and Applications I

Hamilton description of plasmas and other models of matter: structure and applications I P. J. Morrison Department of Physics and Institute for Fusion Studies The University of Texas at Austin [email protected] http://www.ph.utexas.edu/ morrison/ ∼ MSRI August 20, 2018 Survey Hamiltonian systems that describe matter: particles, fluids, plasmas, e.g., magnetofluids, kinetic theories, . Hamilton description of plasmas and other models of matter: structure and applications I P. J. Morrison Department of Physics and Institute for Fusion Studies The University of Texas at Austin [email protected] http://www.ph.utexas.edu/ morrison/ ∼ MSRI August 20, 2018 Survey Hamiltonian systems that describe matter: particles, fluids, plasmas, e.g., magnetofluids, kinetic theories, . \Hamiltonian systems .... are the basis of physics." M. Gutzwiller Coarse Outline William Rowan Hamilton (August 4, 1805 - September 2, 1865) I. Today: Finite-dimensional systems. Particles etc. ODEs II. Tomorrow: Infinite-dimensional systems. Hamiltonian field theories. PDEs Why Hamiltonian? Beauty, Teleology, . : Still a good reason! • 20th Century framework for physics: Fluids, Plasmas, etc. too. • Symmetries and Conservation Laws: energy-momentum . • Generality: do one problem do all. • ) Approximation: perturbation theory, averaging, . 1 function. • Stability: built-in principle, Lagrange-Dirichlet, δW ,.... • Beacon: -dim KAM theorem? Krein with Cont. Spec.? • 9 1 Numerical Methods: structure preserving algorithms: • symplectic, conservative, Poisson integrators, -

Canonical Coordinates on Lie Groups and the Baker Campbell Hausdorff Formula

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2018 Canonical Coordinates on Lie Groups and the Baker Campbell Hausdorff Formula Nicholas Graner Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Graner, Nicholas, "Canonical Coordinates on Lie Groups and the Baker Campbell Hausdorff Formula" (2018). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7232. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7232 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CANONICAL COORDINATES ON LIE GROUPS AND THE BAKER CAMPBELL HAUSDORFF FORMULA by Nicholas Graner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF SCIENCE in Mathematics Approved: Mark Fels, Ph.D. Charles Torre, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member Ian Anderson, Ph.D. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School for Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan,Utah 2018 ii Copyright © Nicholas Graner 2018 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Canonical Coordinates on Lie Groups and the Baker Campbell Hausdorff Formula by Nicholas Graner, Master of Science Utah State University, 2018 Major Professor: Mark Fels Department: Mathematics and Statistics Lie's third theorem states that for any finite dimensional Lie algebra g over the real numbers, there is a simply connected Lie group G which has g as its Lie algebra. -

Hamiltonian Dynamics Lecture 1

Hamiltonian Dynamics Lecture 1 David Kelliher RAL November 12, 2019 David Kelliher (RAL) Hamiltonian Dynamics November 12, 2019 1 / 59 Bibliography The Variational Principles of Mechanics - Lanczos Classical Mechanics - Goldstein, Poole and Safko A Student's Guide to Lagrangians and Hamiltonians - Hamill Classical Mechanics, The Theoretical Minimum - Susskind and Hrabovsky Theory and Design of Charged Particle Beams - Reiser Accelerator Physics - Lee Particle Accelerator Physics II - Wiedemann Mathematical Methods in the Physical Sciences - Boas Beam Dynamics in High Energy Particle Accelerators - Wolski David Kelliher (RAL) Hamiltonian Dynamics November 12, 2019 2 / 59 Content Lecture 1 Comparison of Newtonian, Lagrangian and Hamiltonian approaches. Hamilton's equations, symplecticity, integrability, chaos. Canonical transformations, the Hamilton-Jacobi equation, Poisson brackets. Lecture 2 The \accelerator" Hamiltonian. Dynamic maps, symplectic integrators. Integrable Hamiltonian. David Kelliher (RAL) Hamiltonian Dynamics November 12, 2019 3 / 59 Configuration space The state of the system at a time q 3 t can be given by the value of the t2 n generalised coordinates qi . This can be represented by a point in an n dimensional space which is called “configuration space" (the system t1 is said to have n degrees of free- q2 dom). The motion of the system as a whole is then characterised by the line this system point maps out in q1 configuration space. David Kelliher (RAL) Hamiltonian Dynamics November 12, 2019 4 / 59 Newtonian Mechanics The equation of motion of a particle of mass m subject to a force F is d (mr_) = F(r; r_; t) (1) dt In Newtonian mechanics, the dynamics of the system are defined by the force F, which in general is a function of position r, velocity r_ and time t. -

Canonical Transformations

Chapter 6 Lecture 1 Canonical Transformations Akhlaq Hussain 1 6.1 Canonical Transformations 푁 Hamiltonian formulation 퐻 푞푖, 푝푖 = σ푖=1 푝푖 푞푖ሶ − 퐿 (Hamiltonian) 휕퐻 푝푖ሶ = − 휕푞푖 (푯풂풎풊풕풐풏′풔 푬풒풖풂풕풊풐풏풔) 휕퐻 푞푖ሶ = 휕푝푖 one can get the same differential equations to be solved as are provided by the Lagrangian procedure. 퐿 푞푖ሶ , 푞푖 = 푇 − 푉 (Lagrangian) 푑 휕퐿 휕퐿 − = 0 (Lagrange’s equation) 푑푡 휕푞푖ሶ 휕푞푖 Therefore, the Hamiltonian formulation does not decrease the difficulty of solving Problems. The advantages of Hamiltonian formulation is not its use as a calculation tool, but rather in deeper insight it offers into the formal structure of the mechanics. 2 6.1 Canonical Transformations ➢ In Lagrangian mechanics 퐿 푞푖ሶ , 푞푖 system is described by “푞푖” and velocities” 푞푖ሶ ” in configurational space, ➢ The parameters that define the configuration of a system are called generalized coordinates and the vector space defined by these coordinates is called configuration space. ➢ The position of a single particle moving in ordinary Euclidean Space (3D) is defined by the vector 푞 = 푞(푥, 푦, 푧) and therefore its configuration space is 푄 = ℝ3 ➢ For n disconnected, non-interacting particles, the configuration space is 3푛 ℝ . 3 6.1 Canonical Transformations ➢ In Hamiltonian 퐻 푞푖, 푝푖 we describe the state of the system in Phase space by generalized coordinates and momenta. ➢ In dynamical system theory, a Phase space is a space in which all possible states of a system are represented with each possible state corresponding to one unique point in the phase space. ➢ There exist different momenta for particles with same position and vice versa. -

PHY411 Lecture Notes Part 2

PHY411 Lecture notes Part 2 Alice Quillen October 2, 2018 Contents 1 Canonical Transformations 2 1.1 Poisson Brackets . 2 1.2 Canonical transformations . 3 1.3 Canonical Transformations are Symplectic . 5 1.4 Generating Functions for Canonical Transformations . 6 1.4.1 Example canonical transformation - action angle coordinates for the harmonic oscillator . 7 2 Some Geometry 9 2.1 The Tangent Bundle . 9 2.1.1 Differential forms and Wedge product . 9 2.2 The Symplectic form . 12 2.3 Generating Functions Geometrically . 13 2.4 Vectors generate Flows and trajectories . 15 2.5 The Hamiltonian flow and the symplectic two-form . 15 2.6 Extended Phase space . 16 2.7 Hamiltonian flows preserve the symplectic two-form . 17 2.8 The symplectic two-form and the Poisson bracket . 19 2.8.1 On connection to the Lagrangian . 21 2.8.2 Discretized Systems and Symplectic integrators . 21 2.8.3 Surfaces of section . 21 2.9 The Hamiltonian following a canonical transformation . 22 2.10 The Lie derivative . 23 3 Examples of Canonical transformations 25 3.1 Orbits in the plane of a galaxy or around a massive body . 25 3.2 Epicyclic motion . 27 3.3 The Jacobi integral . 31 3.4 The Shearing Sheet . 32 1 4 Symmetries and Conserved Quantities 37 4.1 Functions that commute with the Hamiltonian . 37 4.2 Noether's theorem . 38 4.3 Integrability . 39 1 Canonical Transformations It is straightforward to transfer coordinate systems using the Lagrangian formulation as minimization of the action can be done in any coordinate system. -

Canonical Transformations

Canonical transformations November 23, 2014 A Recall that we have defined a symplectic transformation to be any linear transformation M B leaving the symplectic form invariant, AB A B CD Ω ≡ M C M DΩ Coordinate transformations, χA ξB which are symplectic transformations at each point are called canonical. Specifically, those functions χA (ξ) satisfying @χC @χD ΩCD ≡ ΩAB @ξA @ξB are canonical transformations. Canonical transformations preserve Hamilton’s equations. 1 Poisson brackets We may also write Hamilton’s equations in terms of Poisson brackets between dynamical variables. By a dynamical variable, we mean any function f = f ξA of the canonical coordinates used to describe a physical system. We define the Poisson bracket of any two dynamical variables f and g by @f @g ff; gg = ΩAB @ξA @ξB The importance of this product is that it is preserved by canonical transformations. We see this as follows. Let ξA be any set of phase space coordinates in which Hamilton’s equations take the form dξA @H = ΩAB (1) dt @ξB and let f and g be any two dynamical variables. Denote the Poisson bracket of f and g in the coordinates A A ξ be denoted by ff; ggξ. In a different set of coordinates, χ (ξ) ; we have @f @g ff; gg = ΩAB χ @χA @χB @ξC @f @ξD @g = ΩAB @χA @ξC @χB @ξD @ξC @ξD @f @g = ΩAB @χA @χB @ξC @ξD Therefore, if the coordinate transformation is canonical so that @ξC @ξD ΩAB = ΩCD @χA @χB 1 we have @f @g ff; gg = ΩAB = ff; gg χ @ξC @ξD ξ and the Poisson bracket is unchanged. -

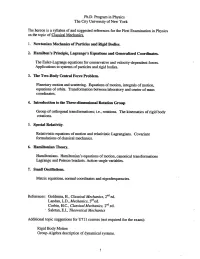

THE CITY UNIVERSITY of NEW YORK First Examination for Phd Candidates in Physics Analytical Dynamics Summer 2010 Do Two of the Following Three Problems

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK First Examination for PhD Candidates in Physics Analytical Dynamics Summer 2010 Do two of the following three problems. Start each problem on a new page. Indicate clearly which two problems you choose to solve. If you do not indicate which problems you wish to be graded, only the first two problems will be graded. Put your identification number on each page. 1. A particle moves without friction on the axially symmetric surface given by 1 z = br2, x = r cos φ, y = r sin φ 2 where b > 0 is constant and z is the vertical direction. The particle is subject to a homogeneous gravitational force in z-direction given by −mg where g is the gravitational acceleration. (a) (2 points) Write down the Lagrangian for the system in terms of the generalized coordinates r and φ. (b) (3 points) Write down the equations of motion. (c) (5 points) Find the Hamiltonian of the system. (d) (5 points) Assume that the particle is moving in a circular orbit at height z = a. Obtain its energy and angular momentum in terms of a, b, g. (e) (10 points) The particle in the horizontal orbit is poked downwards slightly. Obtain the frequency of oscillation about the unperturbed orbit for a very small oscillation amplitude. 2. Use relativistic dynamics to solve the following problem: A particle of rest mass m and initial velocity v0 along the x-axis is subject after t = 0 to a constant force F acting in the y-direction. -

1 Introduction 2 Comprehensive Kinematics and Mathematical Tools

POISSON BRACKET FORMULATION OF A HIGHER-ORDER, GEOMETRICALLY-EXACT BEAM Mayank Chadha1;∗ and Michael D. Todd2 1;2 Department of Structural Engineering, University of California San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla CA 92093-0085 [email protected] and [email protected] Key words: coupled Poisson’s and warping effects; geometrically-exact beam; Hamiltonian structure; large deformations; Poisson bracket formulation Abstract. This paper investigates the Hamiltonian structure and Poisson bracket formulation of a higher-order, geometrically-exact Cosserat type beam with a deforming cross-section in terms of canonically conjugate variables. 1 Introduction In our recent works, we investigated and refined the kinematics of Cosserat beams [1], and then we developed the variational and numerical formulation for a geometrically-exact beam with those improved kinematics [2]. This development incorporated fully-coupled Poisson’s and warping effects, along with the classical deformation effects like bending, torsion, shear, and axial deformation for the case of finite displacement and strain; this allowed us to capture a three dimensional, multi-axial strain fields using single-manifold kinematics. Under the adapted kinematic model, a beam/rod is modeled by a framed spatial curve and a family of deformable cross-sections that can undergo both in-plane and out-of-plane deformation. This paper deals with the Poisson bracket formulation associated with the beam kinematics discussed in [1]. The Poisson bracket formulation constitutes a part of the variational analysis of a mechanical system. In that regard, this paper is a theoretical extension to the variational formulation of the beam discussed in [2] that detailed the governing equation of motion, the associated weak form, and the numerical solution of the equation of motion. -

Steppingstones in Hamiltonian Dynamics

Steppingstones in Hamiltonian dynamics Thomas F. Jordan Physics Department University of Minnesota Duluth, Minnesota 55812 [email protected] Easy steps through essential Hamiltonian dynamics are outlined, from necessary definitions of Poisson brackets and canonical transformations, to a quick proof that Hamiltonian evolution is made by canonical transforma- tions, the quickest proof of Liouville’s theorem, and on to Poincare-Cartan integral invariants and completely integrable dynamics, making room, pro- viding tools, and setting the stage for more recent developments. arXiv:physics/0310140v2 [physics.ed-ph] 9 Dec 2003 1 I. Introduction At a few key points, my teaching of classical mechanics relies on calcu- lations that I do differently from standard texts. Strung together with bits of familiar material, they form an alternative route through Hamiltonian dy- namics that I find advantageous. It fits more easily into a course that moves from traditional to chaotic dynamics. This requires that I provide notes for students. Here I describe points that may be helpful for teachers as well. They supplement what I have found in the standard texts. I take care to refer to the texts I have found most helpful and those that are closest to what I do. New developments in classical mechanics have given Hamiltonian dynamics a new role in our teaching. It helps prepare us to work with the − methods and understand and appreciate the results of chaotic dynamics.1 4 To make room for new developments, we have to delete or reduce some traditional topics. Hamiltonian dynamics involves an accumulated wealth of mathematical development that can be shortened without sacrificing either the basic concepts or the results that illuminate contemporary work. -

Canonical Coordinates for Coadjoint Orbits of Completely Solvable Groups

Journal of Lie Theory Volume 15 (2005) 521–560 c 2005 Heldermann Verlag Canonical Coordinates for Coadjoint Orbits of Completely Solvable Groups Didier Arnal, Mabrouk Ben Ammar, Bradley N. Currey and B´echir Dali ∗ Communicated by J. Ludwig Abstract. We show that when the methods of [2] are combined with the explicit stratification and orbital parameters of [9] and [10], the result is a construction of explicit analytic canonical coordinates for any coadjoint orbit O of a completely solvable Lie group. For each layer in the stratification, the canonical coordinates and the orbital cross-section together constitute an analytic parametrization for the layer. Finally, we quantize the minimal open layer with the Moyal star product and prove that the coordinate functions are in a convenient comple- tion of spaces of polynomial functions on g∗ , for a metric topology naturally related to the star product. Mathematics Subject Index: 22E25, 22E27, 53D55 Key Words and Phrases: Completely solvable Lie groups, Parametrization, Canonical coordinates. 0. Introduction Let G be an exponential Lie group with Lie algebra g, and let O ⊂ g∗ be a coadjoint orbit of G. Then O carries a canonical symplectic structure, meaning that O is equipped with a distinguished, closed two-form ωO with the property that ωO is non-degenerate at each point of O. If (U, c) is chart in O with c = (p1, p2, . , pd, q1, q2, . , qd), then c = (p1, p2, . , pd, q1, q2, . , qd) are called canonical coordinates on U if d X ωO|U = dpr ∧ dqr. r=1 A standard geometric result says that there is a chart for a neighborhood of every point of O with canonical coordinates, and a natural question is to what extent can such coordinates be defined “globally”. -

Contact Hamiltonian Mechanics

Contact Hamiltonian Mechanics Alessandro Bravettia, Hans Cruzb, Diego Tapiasc aInstituto de Investigaciones en Matem´aticas Aplicadas y en Sistemas, Universidad Nacional Aut´onoma de M´exico, A. P. 70543, M´exico, DF 04510, M´exico. bInstituto de Ciencias Nucleares, Universidad Nacional Aut´onoma de M´exico, A. P. 70543, M´exico, DF 04510, M´exico. cFacultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Aut´onoma de M´exico, A.P. 70543, M´exico, DF 04510, Mexico. Abstract In this work we introduce contact Hamiltonian mechanics, an extension of symplectic Hamiltonian mechanics, and show that it is a natural candidate for a geometric description of non-dissipative and dissipative systems. For this purpose we review in detail the major features of standard symplectic Hamiltonian dynamics and show that all of them can be generalized to the contact case. Keywords: Hamiltonian mechanics, Dissipative systems, Contact geometry arXiv:1604.08266v2 [math-ph] 15 Nov 2016 Email addresses: [email protected] (Alessandro Bravetti), [email protected] (Hans Cruz), [email protected] (Diego Tapias) Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Symplectic mechanics of non-dissipative systems 5 2.1 Time-independent Hamiltonian mechanics . 5 2.2 Canonical transformations and Liouville’s theorem . 6 2.3 Time-dependent Hamiltonian systems . 7 2.4 Hamilton-Jacobi formulation . 10 3 Contact mechanics of dissipative systems 11 3.1 Time-independent contact Hamiltonian mechanics . 11 3.2 Time evolution of the contact Hamiltonian and mechanical energy ............................... 15 3.3 Contact transformations and Liouville’s theorem . 17 3.4 Time-dependent contact Hamiltonian systems . 20 3.5 Hamilton-Jacobi formulation .