Stack Effect in Buildings Wilson, A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind- Chimney

WIND-CHIMNEY Integrating the Principles of a Wind-Catcher and a Solar-Chimney to Provide Natural Ventilation A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Architecture by Fereshteh Tavakolinia December 2011 WIND-CHIMNEY Integrating the Principles of a Wind-Catcher and a Solar-Chimney to Provide Natural Ventilation © 2011 Fereshteh Tavakolinia ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: WIND-CHIMNEY Integrating the Principles of a Wind-Catcher and a Solar-Chimney to Provide Natural Ventilation AUTHOR: Fereshteh Tavakolinia DATE SUBMITTED: December 2011 COMMITTEE CHAIR: James A. Doerfler, Associate Department Head COMMITTEE MEMBER: Jacob Feldman, Professor iii WIND-CHIMNEY Integrating the principles of a wind-catcher and a solar chimney to provide natural ventilation Fereshteh Tavakolinia Abstract This paper suggests using a wind-catcher integrated with a solar-chimney in a single story building so that the resident might benefit from natural ventilation, a passive cooling system, and heating strategies; it would also help to decrease energy use, CO2 emissions, and pollution. This system is able to remove undesirable interior heat pollution from a building and provide thermal comfort for the occupant. The present study introduces the use of a solar-chimney with an underground air channel combined with a wind-catcher, all as part of one device. Both the wind-catcher and solar chimney concepts used for improving a room’s natural ventilation are individually and analytically studied. This paper shows that the solar-chimney can be completely used to control and improve the underground cooling system during the day without any electricity. -

Passive and Low Energy Cooling Survey

Environmental Building News - Marc Rosenbaum's Passive and Low Energy Cooling Summary... Page 1 of 14 Home Search Subscribe Features Product Reviews Other Stories Passive and Low Energy Cooling Survey by Marc Rosenbaum, P.E. Marc's other articles 1.0 Comfort 2.0 Psychrometrics 3.0 Conventional Mechanical Cooling Using Vapor Compression 4.0 Loads 5.0 Climate 6.0 Distribution Options 7.0 Dehumidification 8.0 Ventilative Cooling 9.0 Nocturnal Ventilative Cooling 10.0 Night Sky Radiational Cooling 11.0 Evaporative Cooling 12.0 Earth-coupled Cooling 13.0 System Strategies This report documents a survey I made of passive and low energy cooling techniques. It begins with an overview of general cooling issues. The topics covered in the sections following are: comfort, psychrometrics, an overview of mechanical cooling, loads, climate data, distribution options, dehumidification, ventilative cooling, nocturnal ventilative cooling, radiant cooling, evaporative cooling, earth-coupled cooling, and combined system strategies. Principal references were Passive Cooling, edited by Jeffrey Cook, and Passive and Low Energy Cooling of Buildings, by Baruch Givoni. Both books are primarily academic in nature, but Givoni in particular provides plenty of actual field data. These books don't necessarily represent the state- of-the-art: Cook was published in 1989, and Givoni in 1994. As we decide which direction to pursue, we will seek more current information. The physics are unlikely to change much, however. The usual caveat applies: I am not expert in any of these applications, and all errors herein are mine. 1.0 Comfort Buildings are cooled primarily to enhance human comfort. -

Improving Stack Effect in Hot Humid Building Interiors with Hybrid Turbine Ventilator(S)

MAT EC Web of Conferences 17, 01012 (2014) DOI: 10.1051/matecconf/20141701012 C Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2014 Improving Stack Effect in Hot Humid Building Interiors with Hybrid Turbine Ventilator(s) Radia Tashkina Rifa1, Karam M. Al-Obaidi2 , Abdul Malek Abdul Rahman3,a 1,2,3School of Housing, Building and Planning, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800, Penang, Malaysia Abstract. Natural ventilation strategies have been applied through the ages to offer thermal comfort. At present, these techniques could be employed as one of the methods to overcome the electric consumption that comes from the burning of disproportionate fossil fuel to operate air conditioners. This air conditioning process is the main contributor of CO2 emissions. This paper focuses on the efficiency of stack ventilation which is one of the natural ventilation strategies, and at the same time attempts to overcome the problem of erratic wind flow and the low indoor/outdoor temperature difference in the hot, humid Malaysian climate. Wind flow and sufficient pressure difference are essential for stack ventilation, and as such the irregularity can be overcome with the use of the Hybrid Turbine Ventilator (HTV) which extracts hot air from the interior of the building via the roof level. The extraction of hot air is constant and consistent throughout the day time as long as there is sunlight falling on the solar panel for solar electricity. The aim of this paper is to explore the different HTV strategies and find out which building dimensions is most expected to reduce maximum indoor air temperature of a given room in a real weather condition. -

The Wind-Catcher, a Traditional Solution for a Modern Problem Narguess

THE WIND-CATCHER, A TRADITIONAL SOLUTION FOR A MODERN PROBLEM NARGUESS KHATAMI A submission presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glamorgan/ Prifysgol Morgannwg for the degree of Master of Philosophy August 2009 I R11 1 Certificate of Research This is to certify that, except where specific reference is made, the work described in this thesis is the result of the candidate’s research. Neither this thesis, nor any part of it, has been presented, or is currently submitted, in candidature for any degree at any other University. Signed ……………………………………… Candidate 11/10/2009 Date …………………………………....... Signed ……………………………………… Director of Studies 11/10/2009 Date ……………………………………… II Abstract This study investigated the ability of wind-catcher as an environmentally friendly component to provide natural ventilation for indoor environments and intended to improve the overall efficiency of the existing designs of modern wind-catchers. In fact this thesis attempts to answer this question as to if it is possible to apply traditional design of wind-catchers to enhance the design of modern wind-catchers. Wind-catchers are vertical towers which are installed above buildings to catch and introduce fresh and cool air into the indoor environment and exhaust inside polluted and hot air to the outside. In order to improve overall efficacy of contemporary wind-catchers the study focuses on the effects of applying vertical louvres, which have been used in traditional systems, and horizontal louvres, which are applied in contemporary wind-catchers. The aims are therefore to compare the performance of these two types of louvres in the system. For this reason, a Computational Fluid Dynamic (CFD) model was chosen to simulate and study the air movement in and around a wind-catcher when using vertical and horizontal louvres. -

Solar Chimneys for Residential Ventilation

SOLAR CHIMNEYS FOR RESIDENTIAL VENTILATION Pavel Charvat, Miroslav Jicha and Josef Stetina Department of Thermodynamics and Environmental Engineering Faculty of Mechanical Engineering Brno University of Technology Technicka 2, 616 69 Brno, Czech Republic ABSTRACT An increasing impact of ventilation and air-conditioning to the total energy consumption of buildings has drawn attention to natural ventilation and passive cooling. The very common way of natural ventilation in residential buildings is passive stack ventilation. The passive stack ventilation relies on the stack effect created by the temperature difference between air temperature inside and outside a building. A solar chimney represents an option how to improve the performance of passive stack ventilation on hot sunny days, when there is a small difference between indoor and outdoor air temperature. The full-scale solar chimneys have been built and tested at the Department of Thermodynamics and Environmental Engineering at the Brno University of Technology. The main goal of the experiments is to investigate performance of solar chimneys under the climatic conditions of the Czech Republic. Two different constructions of a solar chimney have been tested; a light weight construction and the construction with thermal mass. KEYWORDS solar chimney, residential ventilation, passive cooling PRINCIPLE OF SOLAR CHIMNEY VENTILATION A solar chimney is a natural-draft device that uses solar radiation to move air upward, thus converting solar energy (heat) into kinetic energy (motion) of air. At constant pressure air density decreases with increasing temperature. It means that air with higher temperature than ambient air is driven upwards by the buoyancy force. A solar chimney exploits this physical phenomenon and uses solar energy to heat air up. -

Indoor Air Quality, the House As a System and Vented Combustion

Michael J. Van Buren, P.E. Blazing Design, Inc. 49 Commerce Ave, 6A S. Burlington, Vermont 05403 (p) 802-318-6973 Email – [email protected] Fireplace Design “The House as a System” House as a System What does it mean, The “House as a System”? The house as a system refers to how air moves in, out and around a house. Air moves in and out of a house through the “building envelope”. Why Consider the “House as a System”? Many chimneys fail to operate because of aspects of the house and its surroundings. If air flows out of a house, air must flow back into the house Pressure Differences, What Pressure Differences? My Ears Don’t Even Pop! 1 Pound per square inch (Psi) = 27.71 inches of water column (W.C.) 0.1 inch water column (W.C.) = 25 Pascals (PA) House pressures range from 5 to –25 PA What Causes These Air Pressure Differences? Appliances that take air out of the house Exhaust fans – bathrooms, kitchens Clothes dryers Furnaces Atmospherically vented combustion appliances; fireplaces, furnaces, boilers, hot water heaters. Typical Air Flows of Exhaust Fans Device Air Flow (CFM) Bathroom Fan 32-64 Standard Kitchen Fan 85-127 Downdraft Kitchen Fan 210-425 Clothes Dryer 85-160 Central Vacuum 50-110 When air goes out - more air must come in! Fireplace Needs Other Causes affecting Air Pressure Differences The Not-So Obvious Reasons Buoyancy of warm air – “Stack Effect” Wind Furnaces Buoyancy of Warm Air? Everyone knows hot air rises – Why? Hot air is lighter than cold air (air expands when it is heated) That’s why candle flames go up That’s why hot air goes up a chimney Buoyancy of hot air causes a pressure difference in the house relative to the outside pressure which is called “Stack Effect” Stack Effect? Stack Effect - The pressure difference created between the warmer air in a building and the colder air outside. -

Factors Affecting Indoor Air Quality

Factors Affecting Indoor Air Quality The indoor environment in any building the categories that follow. The examples is a result of the interaction between the given for each category are not intended to site, climate, building system (original be a complete list. 2 design and later modifications in the Sources Outside Building structure and mechanical systems), con- struction techniques, contaminant sources Contaminated outdoor air (building materials and furnishings, n pollen, dust, fungal spores moisture, processes and activities within the n industrial pollutants building, and outdoor sources), and n general vehicle exhaust building occupants. Emissions from nearby sources The following four elements are involved n exhaust from vehicles on nearby roads Four elements— in the development of indoor air quality or in parking lots, or garages sources, the HVAC n loading docks problems: system, pollutant n odors from dumpsters Source: there is a source of contamination pathways, and or discomfort indoors, outdoors, or within n re-entrained (drawn back into the occupants—are the mechanical systems of the building. building) exhaust from the building itself or from neighboring buildings involved in the HVAC: the HVAC system is not able to n unsanitary debris near the outdoor air development of IAQ control existing air contaminants and ensure intake thermal comfort (temperature and humidity problems. conditions that are comfortable for most Soil gas occupants). n radon n leakage from underground fuel tanks Pathways: one or more pollutant pathways n contaminants from previous uses of the connect the pollutant source to the occu- site (e.g., landfills) pants and a driving force exists to move n pesticides pollutants along the pathway(s). -

MODELING a SOLAR CHIMNEY for MAXIMUM SOLAR IRRADIATION and MAXIMUM AIRFLOW, for LOW LATITUDE LOCATIONS Leticia Neves1, Maurício

Proceedings of Building Simulation 2011: 12th Conference of International Building Performance Simulation Association, Sydney, 14-16 November. MODELING A SOLAR CHIMNEY FOR MAXIMUM SOLAR IRRADIATION AND MAXIMUM AIRFLOW, FOR LOW LATITUDE LOCATIONS Leticia Neves1, Maurício Roriz2 and Fernando Marques da Silva3 1State University of Campinas, Brazil 2Federal University of Sao Carlos, Brazil 3National Laboratory of Civil Engineering, Lisbon, Portugal example. ABSTRACT The solar chimney is composed by a solar collector Numerous researches have shown the possibility to with two parallel plates – a glass cover and an enhance indoor natural ventilation in buildings by absorber plate – that heats up the air, enhancing the using inclined solar chimneys, although most of them greenhouse effect and inducing it to move upwards. usually include determining an optimum tilt for the Consequently, air from the internal space moves absorber, considering an inclination angle between towards the chimney inlet and outdoor air enters the maximum solar irradiation and best stack height. space through the inlet openings of the room (Figure This paper resumes the investigation of a possibility 1). to optimize solar irradiation on the absorber plane The efficiency of solar chimneys depends, among and also guarantee a considerable stack height, by other factors, on the intensity of solar radiation that using a chimney extension, which would be reaches the glass cover. Since the angle of incidence responsible to maintain a minimum height for the of solar radiation on a surface varies with latitude and system, independently from the absorber inclination. time of the year, it becomes advantageous using Results of a building simulation were compared with inclined solar chimneys at locations near the Equator, outputs from an experimental test cell for calibration. -

Basics of Psychrometrics Practical Heat Load Calculation

Basics of Psychrometrics Practical Heat Load Calculation Webinar 30 April 2020 Vikram Murthy ASHRAE Mumbai Chapter Sessions ►Basics of Psychrometrics ►All about Heat ►Practical Heat Load (Cooling Load) Calculation ( Using the E 20 , CLTD - Cooling Load Temperature Difference Method ) Psychrometric basics Psychrometrics ► A hundred and eighteen years ago, Willis Carrier, developed a method that allows us to visualize two of the variables -- the combination of air temperature and humidity that exist in a space. The tool he developed is called the Psychrometric Chart. ► Psychrometrics, which Willis Carrier developed, is the study of the mixture of dry air and water , and is the scientific basis of Air conditioning . Willis Carrier Willis began his first job at the Buffalo Forge Company . Solving a Problem at the Sackett Wilhelm Lithographing Company in Brooklyn, he formulated the Laws of Psychrometrics . Willis Carrier laid down the Equations of Psychrometrics in 1902 . The Carrier Company he founded developed the Centrifugal Chiller and the Weathermaker, that we call an Air Handling Unit or AHU . Purpose Of Comfort Airconditioning ►To Cool or Heat ►To Dehumidify or Humidify (remove or add moisture) ►To remove odours ►To remove particulate & microbial pollutants Definitions Of Air ► Air is a vital component of our everyday lives. ► Psychrometrics refers to the properties of moist air. ► Dry air ► Moist air ► Moist air and atmospheric air can be considered to mean the same Units ► We work in INCH POUND system of units, IP units. (The other unit system in use is SI units) Units of length: ft, inches. Units of area: sq.ft Units of volume: cu.ft. -

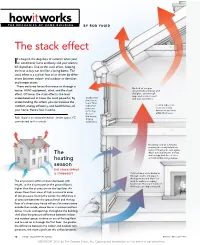

The Stack Effect

howitworks THE MECHANICS OF HOME BUILDING BY ROB YAGID The stack effect t’s August, the dog days of summer, when your Iair conditioner hums endlessly and your electric bill skyrockets. Due to the stack effect, keeping the heat at bay can feel like a losing battle. The stack effect is a cyclical flow of air driven by differ- ences between indoor- and outdoor-air densities and temperatures. There are three forces that move air through a Heated air escapes house: HVAC equipment, wind, and the stack around leaky windows and effect. Of these, the stack effect is the least skylights, and through gaps and cracks in roof understood and at times the most powerful. By Outdoor-air and wall assemblies. pressure is understanding this effect, you can increase the lower than comfort, energy efficiency, and healthfulness of indoor-air Heated indoor air pressure floats on colder, your home. Here’s how it works. in the top denser air and rises floor of within the house. Rob Yagid is an associate editor. James Lyons, PE, the house, driving contributed to this article. exfiltration. Incoming cold air is heated, starting the nearly relentless cycle of flowing air over again, which not only wastes money The and energy, but also creates heating uncomfortable living spaces. season THE STACK EFFECT IS STRONGEST Cold outdoor air is drawn in through cracks and gaps in the basement and first-floor The air pressure within a house decreases with walls to replace escaping height, so the air pressure on the ground floor is heated air. The lower levels of the house are depressurized. -

How They Waste Energy and Rot Houses One-Third of the Energy You Buy Probably Leaks Through Holes in Your House

BY JOHN STRAUBE topping air is the second-most-important job worse. energy efficiency requires a tight shell; good Leaky rim of a building enclosure. Next to rain, air leaks indoor-air quality requires fresh outdoor air. Ideally, the joists matter. Floor and wall through walls, roofs, and floors can have the most fresh air should come not from random accidental leaks connections damaging effect on the durability of a house. of unknown size and quantity, but from a known source offer many air- SUncontrolled airflow through the shell not only carries at a known rate. For this to happen, the house needs an leakage oppor- moisture into framing cavities, causing mold and rot, but adequate air barrier and a controlled ventilation path. tunities. The wall sheathing it also can account for a huge portion of a home’s energy In a leaky house, large volumes of air—driven by on this house use and can cause indoor-air-quality problems. exhaust fans, the stack effect, and wind—can blow in Minnesota A tight house is better than a leaky house, with a caveat: through the floor, walls, and ceiling. because air usually experienced A tight house without a ventilation system is just as bad contains water vapor, these uncontrolled air leaks can serious rot because duct- as a leaky house with no ventilation system—maybe cause condensation, mold, and rot—as seen below. work in the floor framing pulled moist air into poorly sealed rim joists. AIR LEAKS How They Waste Energy and Rot Houses One-third of the energy you buy probably leaks through holes in your house www.finehomebuilding.com Photo this page: courtesy of the builders Association of minnesota OcTOber/NOvember 2012 45 COPYRIGHT 2012 by The Taunton Press, Inc. -

Natural Ventilation: Theory

NaturalNatural Ventilation:Ventilation: TheoryTheory HalHal LevinLevin 1 1 2 2 1 Natural Ventilation: Theory Definitions Purpose of ventilation • What is ventilation? Types of natural ventilation (Driving forces): • Buoyancy (stack effect; thermal) • Pressure driven (wind driven; differential pressure) Applications • Supply of outdoor air • Convective cooling • Physiological cooling Issues • Weather-dependence: wind, temperature, humidity • Outdoor air quality • Immune compromised patients • Building configuration (plan, section) • Management of openings 3 Natural and Mixed Mode Ventilation Mechanisms Natural Ventilation Mixed Mode Ventilation Cross Flow Wind Wind Tower Stack (Flue) Stack (Atrium) Mixed Mode Ventilation heated/cooled chilled pipes ceiling void Sketch of school system heated/cooled pipes Sketch of B&O Building Fan Assisted Stack Top Down Ventilation Buried Pipes 4 4 Courtesy of Martin Liddament via Yuguo Li 2 Climate Typology (oversimplified!) Not in handout materials – to be completed by class Climate type Diurnal Steady daily Seasonal No seasonal swing cycle variation variation Hot humid Singapore Hot dry Low desert Temperate humid London Milan, Italy Temperate dry High desert Quito, Ecuador Temperate Boston Lima Montreal, seasonal -- Temp Canada Temperate San seasonal – RH Francisco Mt. Fuji Cold humid Cold dry Bogotá 6 What is ventilation? Definitions covering ventilation and the flow of air into and out of a space include: • Purpose provided (intentional) ventilation: Ventilation is the process by which ‘clean’ air (normally outdoor air) is intentionally provided to a space and stale air is removed. This may be accomplished by either natural or mechanical means. • Air infiltration and exfiltration: In addition to intentional ventilation, air inevitably enters a building by the process of ‘air infiltration’.