Ranunculus Diminutus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enrolment and Election Booklet 2020-21

The Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania Enrolment and election booklet 2020-21 Includes: Procedures and guidelines June 2020 Contents THE ABORIGINAL LAND COUNCIL OF TASMANIA (ALCT) ............................... 3 Definitions of the 5 electoral areas THE ALCT ELECTORS ROLL ........................................................................ 4 The Preliminary Roll Who is entitled to be on the Roll Objections to transfer from the Preliminary Roll to the Roll GUIDELINES CONCERNING THE REQUIREMENTS SET OUT IN SECTION 3A OF THE ABORIGINAL LANDS ACT 1995 ..................................................................... 6 Aboriginal ancestry Self-identification Communal recognition PROCEDURE FOR DEALING WITH OBJECTIONS TO ENROLMENT ....................... 8 ELECTORAL COMMISSIONER’S REVIEW COMMITTEE ...................................... 9 CONDUCT OF ALCT ELECTIONS ................................................................. 10 How to stand as a candidate for election Eligibility to stand How to vote How votes are counted Declaration of the result Term of office Filling a casual vacancy 2020 - 21 ALCT ELECTION TIMETABLE ...................................... BACK COVER 2020-21 ALCT Election Procedures & Guidelines June 2020 2 The Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania The Aboriginal Lands Act 1995 (the Act) provides for the election of members of the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania (ALCT). ALCT holds and manages Aboriginal land on behalf of the Aboriginal people of Tasmania. The ALCT comprises 8 members, elected for a term of approximately -

Overview of Tasmania's Offshore Islands and Their Role in Nature

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 154, 2020 83 OVERVIEW OF TASMANIA’S OFFSHORE ISLANDS AND THEIR ROLE IN NATURE CONSERVATION by Sally L. Bryant and Stephen Harris (with one text-figure, two tables, eight plates and two appendices) Bryant, S.L. & Harris, S. 2020 (9:xii): Overview of Tasmania’s offshore islands and their role in nature conservation.Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 154: 83–106. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.154.83 ISSN: 0080–4703. Tasmanian Land Conservancy, PO Box 2112, Lower Sandy Bay, Tasmania 7005, Australia (SLB*); Department of Archaeology and Natural History, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601 (SH). *Author for correspondence: Email: [email protected] Since the 1970s, knowledge of Tasmania’s offshore islands has expanded greatly due to an increase in systematic and regional surveys, the continuation of several long-term monitoring programs and the improved delivery of pest management and translocation programs. However, many islands remain data-poor especially for invertebrate fauna, and non-vascular flora, and information sources are dispersed across numerous platforms. While more than 90% of Tasmania’s offshore islands are statutory reserves, many are impacted by a range of disturbances, particularly invasive species with no decision-making framework in place to prioritise their management. This paper synthesises the significant contribution offshore islands make to Tasmania’s land-based natural assets and identifies gaps and deficiencies hampering their protection. A continuing focus on detailed gap-filling surveys aided by partnership restoration programs and collaborative national forums must be strengthened if we are to capitalise on the conservation benefits islands provide in the face of rapidly changing environmental conditions and pressure for future use. -

Alphabetical Table Of

TASMANIAN ACTS AND STATUTORY RULES TASMANIAN ACTS N – R AND STATUTORY RULES Nation Building and Jobs Plan Facilitation (Tasmania) Act 2009, No. 5 of 2009 (commenced 27 April 2009) Last consolidation: 31 December 2012 (includes changes under the Legislation Publication Act 1996 in force as at 31 December 2012) Amendments commenced in 2009 – 2016: Nation Building and Jobs Plan Facilitation (Tasmania) Act 2009, No. 5 of 2009 (commenced 31 December 2012) – the Act, except Pt. 1 (ss. 1-4) and s. 18 expired 31 December 2012 unless earlier by notice made by the Treasurer National Broadband Network (Tasmania) Act 2010, No. 48 of 2010 (commenced 21 December 2010) Last consolidation: 16 August 2017 (up to and including amendment by the Aboriginal Relics (Consequential Amendments) Act 2017 and changes under the Legislation Publication Act 1996 in force as at 16 August 2017) Amendments commenced in 2017: Building (Consequential Amendments) Act 2016, No. 12 of 2016 (commenced 1 January 2017) – amended s. 28(c) Aboriginal Relics (Consequential Amendments) Act 2017, No. 17 of 2017 (commenced 16 August 2017) – amended s. 28 National Energy Retail Law (Tasmania) Act 2012, No. 11 of 2012 (commenced 1 July 2012, see S.R. 2012, No. 49) Last consolidation: 1 June 2013 (up to and including amendment by the Electricity Reform (Implementation) Act 2013 and changes under the Legislation Publication Act 1996 in force as at 1 June 2013) Amendments commenced in 2012 – 2016: Electricity Reform (Implementation) Act 2013, No. 5 of 2013 (commenced 1 June 2013) – amended ss. 15 and 18; inserted 17A Regulations: National Energy Retail Law (Tasmania) Regulations 2012 (2012/51 amended by 2013/27) National Energy Retail Law (Tasmania) s. -

Rapid and Repeated Origin of Insular Gigantism and Dwarfism in Australian Tiger Snakes

Evolution, 59(1), 2005, pp. 226±233 RAPID AND REPEATED ORIGIN OF INSULAR GIGANTISM AND DWARFISM IN AUSTRALIAN TIGER SNAKES J. SCOTT KEOGH,1 IAN A. W. SCOTT, AND CHRISTINE HAYES School of Botany and Zoology, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 0200, Australia 1E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. It is a well-known phenomenon that islands can support populations of gigantic or dwarf forms of mainland conspeci®cs, but the variety of explanatory hypotheses for this phenomenon have been dif®cult to disentangle. The highly venomous Australian tiger snakes (genus Notechis) represent a well-known and extreme example of insular body size variation. They are of special interest because there are multiple populations of dwarfs and giants and the age of the islands and thus the age of the tiger snake populations are known from detailed sea level studies. Most are 5000±7000 years old and all are less than 10,000 years old. Here we discriminate between two competing hypotheses with a molecular phylogeography dataset comprising approximately 4800 bp of mtDNA and demonstrate that pop- ulations of island dwarfs and giants have evolved ®ve times independently. In each case the closest relatives of the giant or dwarf populations are mainland tiger snakes, and in four of the ®ve cases, the closest relatives are also the most geographically proximate mainland tiger snakes. Moreover, these body size shifts have evolved extremely rapidly and this is re¯ected in the genetic divergence between island body size variants and mainland snakes. Within south eastern Australia, where populations of island giants, populations of island dwarfs, and mainland tiger snakes all occur, the maximum genetic divergence is only 0.38%. -

Aboriginal Lands Act 1995 (Tas) [Transcript

[Tasmanian Coat of Arms] TASMANIA _______________ ABORIGINAL LANDS ACT 1995 _______________ No. 98 of 1995 _______________ TABLE OF PROVISIONS PART 1 PRELIMINARY 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Interpretation 4. Act binds Crown PART 2 ABORIGINAL LAND COUNCIL OF TASMANIA Division 1 – Establishment and constitution of Council [Seal] 5. Establishment of Council 6. Constitution of Council Division 2 – Election of Members of Council 7. Timing of elections 8. Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania Electors Roll 9. Who is entitled to be on the Roll 10. Entering of names on the Roll 11. Availability of Roll 12. Conduct of elections 13. Who may vote 14. Who may stand for election 15. Counting of votes 16. Certificate of election 17. Costs of elections [Received from the Clerk of the Legislative Council on the 20th day of November 1995. I. Ritchard Registrar Supreme Court] ii Division 3 – Functions and powers of Council 18. Functions and powers of Council 19. Review of Council’s decisions Division 4 – Staff 20. Staff Division 5 – Finances of the Council 21. Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania Fund 22. Application of Fund 23. Bank accounts 24. Temporary investment of funds 25. Accounts and records 26. Audit PART 3 ABORIGINAL LAND 27. Land vested in Council 28. Existing leases and licences 29. Appeals in respect of Council’s decisions in relation to leases and licences 30. Council precluded from mortgaging, &c., Aboriginal land 31. Local management of certain areas 32. Management plans 33. Folio of Register to be created for Aboriginal land 34. Stamp duty and charges not payable 35. -

Reptiles from the Islands of Tasmania(PDF, 530KB)

REPTILES FROM THE ISLANDS OF TASMANIA R.H. Green and J.L. Rainbird June 1993 TECHNICAL REPORT 1993/1 QUEEN VICTORIA MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY LAUNCESTON Reptiles from the islands of Tasmania by R.H. Green and J.L. Rainbird Queen VICtoria Museum, Launceston ABSTRACT Records of lizards and snakes from 110 islands within the pOlitical boundaries of Tasmania are summarised. Dates, literature, references and materials collected are given, together with some comments on numerical status and breeding conditions. INTRODUCTION Very little has been published on the distribution of reptiles which occur on the smaller islands around Tasmania. MacKay (1955) gave some notes on a collection of reptiles from the Furneaux Islands. Rawlinson (1967) listed and discussed records of 13 species from the Furneaux Group and 10 species from King Island. Green (1969) recorded 12 species from Flinders Island and Mt Chappell Island and Green and McGarvie (1971) recorded 9 spedes from King Island following fauna surveys In both locations. Rawlinson (1974) listed 15 species as occurring on the Tasmanian mainland, 12 on islands in the Furneaux Group and 9 on King Island. Hutchinson et al. (1989) gave some known populations of Pseudemoia pretiosa on islands off the southern coast, and haphazard and opportunistic collecting has produced occasional records from various small islands over the years. In 1984 Nigel Brothers, a field biologist with the Tasmanian Department of Environment and Parks, Wildlife and Heritage, commenced a programme designed to gain a greater knowledge of the small and uninhabited isrands around Tasmania. The survey Involved landing on rocks and small islands which might support vegetation and fauna and to record observations and collect specimens. -

Geococcus Pusillus (Earth Cress)

GeococcusListing Statement forpusillus Geococcus pusillus (earth cress) earth cress T A S M A N I A N T H R E A T E N E D S P E C I E S L I S T I N G S T A T E M E N T (Permission from the RBG of Victoria) Scientific name: Geococcus pusillus J.Drumm. ex Harv., Hook. J. Bot. Kew Gard. Misc. 7: 52 (1855) Common name: earth cress (Wapstra et al. 2005) Group: vascular plant, dicotyledon, family Brassicaceae Status: Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 : rare Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 : Not listed Distribution: Endemic status: Not endemic to Tasmania Tasmanian NRM Regions: North, Cradle Coast Figure 1. The distribution of Geococcus pusillus within Plate 1. Geococcus pusillus Tasmania (permission from the RBG of Victoria) 1 Threatened Species Section – Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Listing Statement for Geococcus pusillus (earth cress) IDENTIFICATION AND ECOLOGY DISTRIBUTION AND HABITAT Geococcus pusillus is an annual herb that emerges With the exception of Queensland and the in years of favourable cool-season rainfall Northern Territory, this species is widespread (Cunningham et al. 1992). While it is usually on mainland Australia. In Tasmania, Geococcus found in low numbers, it can cover large areas pusillus is known to be extant in only three in favourable conditions. This implicates locations on separate islands (Mount Chappell, recruitment from soil-stored seed with the Mile and Little Chalky islands) to the west of pendulant seed pods often becoming buried Flinders Island in the Furneaux Group, and the when the pedicels bend back and elongate. -

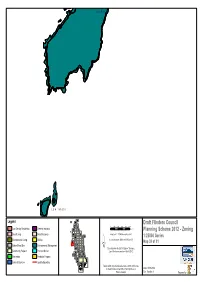

Draft Flinders Council Planning Scheme 2012

Joins Map 34 L o w I s l e t s Legend Draft Flinders Council 0 200 400 600 800 1,000 Low Density Residential General Industrial Metres Planning Scheme 2012 - Zoning Rural Living Rural Resource Map Scale 1 : 25,000 when printed at A3 1:25000 Series Environmental Living Utilities Coordinate System: GDA 1994 MGA Zone 55 Map 39 of 81 Urban Mixed Use Environmental Management ´ Base data from theLIST, © State of Tasmania Community Purpose Port and Marine Land title data current as of 30/04/2012 Recreation Particular Purpose General Business Locality Boundary Before taking any action based on data shown on this map it should first be verified with a Planning Officer of Date: 15/05/2012 Flinders Council. Doc. Version: 0 Prepared by L o Joins Map 35 n g g P o i n t t R o a d Whitemark Chalky Island Joins Map 41 Reef Island Mile Island Little Chalky Island R e e f I s l a n d Isabella Island Legend Draft Flinders Council 0 200 400 600 800 1,000 Low Density Residential General Industrial Metres Planning Scheme 2012 - Zoning Rural Living Rural Resource Map Scale 1 : 25,000 when printed at A3 1:25000 Series Environmental Living Utilities Coordinate System: GDA 1994 MGA Zone 55 Map 40 of 81 Urban Mixed Use Environmental Management ´ Base data from theLIST, © State of Tasmania Community Purpose Port and Marine Land title data current as of 30/04/2012 Recreation Particular Purpose General Business Locality Boundary Before taking any action based on data shown on this map it should first be verified with a Planning Officer of Date: 15/05/2012 Flinders Council. -

List of References

43 LIST OF REFERENCES 1. Aboriginal Lands Act 1995. 2. Aboriginal Lands Amendment (Wybalenna) Act 1999. 3. Aboriginal Lands Amendment Bill 1999. 4. Aird MLC, Hon Michael, Hansard, Legislative Council, 30 November 1999. 5. Bacon MHA, Premier, Jim, Transcript of Briefing, 1 February 2000. 6. Bingham, Mr Richard, Chairman, Aboriginal Land and Cultural Issues Working Group, Transcript of Evidence, 1 February and 10 April 2000. 7. Britton, Mr Ross, Arthur-Pieman Coalition, Transcript of Evidence, 16 March 2000. 8. Brown, Mr Greg, Department of Premier and Cabinet, Transcript of Evidence, 1 February 2000. 9. Circular Head Council, Transcript of Evidence, 14 March 2000. 10. Clark, Mr John, Tasmanian Regional Aboriginal Council, Transcript of Evidence, 16 March 2000. 11. Commonwealth Document, www.ilc.gov.au 12. Cooper, Mrs Helen, Tasmanian Outer Islands Association, Transcript of Evidence, 22 February 2000. 13. Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation, Corroboree 2000 : Towards Reconciliation. 14. Federal Court of Australia Decision, Edwina Shaw & Another v Charles Wolf & Others, [1998] 389 FAC (20 April 1998). 15. Flinders Island Council, Transcript of Evidence, 22 February 2000. 16. Gillies, Mrs Joy, Transcript of Evidence, 14 March 2000. 17. Government Media Statement, 12 October 1999. 18. Groom, Premier, Mr Ray, Second Reading Speech on Aboriginal Lands Bill 1995, 24 October 1995. 19. Herron MP, Senator John, Transcript of Meeting, 16 February 2000. 20. Hobart Quaker Peace and Justice Committee, Transcript of Evidence, 10 April 2000. 44 21. House, Mr Lyell, Forest, Transcript of Evidence, 14 March 2000. 22. Innes-Smith, Mr Peter, Submission to Legislative Council Select Committee on Aboriginal Lands, 23 January 2000. -

Working for Our Country a Review of the Economic and Social Benefits of Indigenous Land and Sea Management

Working for Our Country A review of the economic and social benefits of Indigenous land and sea management November 2015 Contents 1 Foreword 3 Executive summary 10 1. Overview 1.1 Purpose of this report 11 1.2 Structure 11 12 Part 1: A national perspective 13 2. Overview of ranger programs 2.1 Working on Country 13 2.2 Indigenous Protected Area program 15 2.3 Investment in ranger and IPA programs 15 2.4 Key achievements 17 21 3. Economic and social benefits 3.1 A benefit framework 22 3.2 Valuing the benefits 28 3.3 Contributions to closing the gap 28 3.4 Success factors 30 3.5 Developmental phases of ranger groups 32 35 4. Case studies 45 5. A principled approach for the way forward 46 Part 2: Indigenous Ranger groups in the Kimberley, Western Australia 47 6. Kimberley Indigenous Ranger groups 6.1 Introduction 47 6.2 The Kimberley Land Council’s ranger network 47 6.3 State-managed ranger groups 51 6.4 Future directions 53 54 7. References Figures and tables Figure 1 Cumulative Number of Indigenous Ranger Positions and Funding (Actual and Projected, 2007-18) 16 Figure 2 Cumulative Number of Declared IPAs and Annual Program Funding (Actual and Projected, 2009-10 to 2017-18) 17 Figure 3 Indigenous Employment by Status and Gender, Working on Country Program (2011-12) 18 Figure 4 Working on Country Staff Retention over a 12 month period (2009-10 and 2011-12) 18 Figure 5 Type of Training Completed 19 Figure 6 Ranger Groups Undertaking Environmental, Cultural and Economic Activities (2011-12) 19 Figure 7 Types of Commercial Activities Undertaken -

Aboriginal Historical Places

Aboriginal Historical Places lutruwita is the country of Tasmanian Aboriginal people and everyone has a responsibility to protect our heritage. Aboriginal historical places are event. It may have associations with an locations that have significance to important person or be an example A Tasmanian Aboriginal historical Tasmanian Aboriginal people. of wider political, social, spiritual, place may be a site of economic or historic events or trends. An Aboriginal historical place could be • pre-colonial Aboriginal life the site of ancestral life, a colonial era An Aboriginal historical place could • past interactions between massacre, or another significant historic have a physical artefact (tangible Aboriginal people and colonists heritage) such as a rock marking, • a Government policy or action shell midden, foundations, burial or a towards Aboriginal people building. The significance may be in the intangible heritage of ceremony, story • association with a significant or song of a place. The historical place Aboriginal person or group may have both tangible and intangible heritage. Aboriginal historical places are identified through research that may include oral histories, archival sources, historical records and archaeological investigations. AboriginalDepartment Heritage of Tasmania DepartmentPrimary Industr of Primaryies, Park s,Industries, Water and Parks, Env ironmenWater andt Environment Indigenous Protected Areas are areas that are voluntarily dedicated by Aboriginal groups as part of the National Reserve System. In Tasmania these -

Tasmanian Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Submission to the House of Representatives Standing

Attachment 2 Tasmanian Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment submission to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy inquiry into the problem of feral and domestic cats in Australia a. The prevalence of feral and domestic cats in Australia Feral cats are distributed across all habitats on mainland Tasmania as well as the large inhabited islands of King, Flinders, Cape Barren and Bruny. Of the smaller 334 Tasmanian offshore islands, 30 have been recorded with cats (Felis catus) at some point after European settlement, with current data indicating 14 still have feral cats (refer Table 1). Successful feral cat eradications have occurred on six Tasmanian islands (i.e. Little Green, Great Dog, Macquarie, Tasman, Wedge and historically Betsey Island). Cats have likely died out from seven islands (i.e. Deal, Outer Sister, Courts, Fulham, Swan, Schouten and St. Helens Island). Possible or unconfirmed cat sign has been recorded for four other islands (i.e. Philips, Inner Sister, Little Green and Pelican Island). The density of feral cat populations varies across the State. A number of published and unpublished reports (~28) on feral cats in Tasmania have estimated density between (0.02 – 68.20 cats/km2) (Legge et al. 2016). Generalised trends in the density estimate data suggest a gradient of relatively lower densities in the southern and western wilderness areas (~ 0.02- 0.1 cats/km2) through to high densities in the eastern part of the state (~0.5- 1.5 cats /km2). Tasmania’s offshore islands can maintain high densities (~2.0 – 68.20 cats /km2) (Legge et al.