Environmental Taxation in the United States: the Long View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taxation: State and Local Ronald H

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 18 Article 15 Issue 2 Winter 1986 1985-1986 Illinois Law Survey 1986 Taxation: State and Local Ronald H. Jacobson Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Taxation-State and Local Commons Recommended Citation Ronald H. Jacobson, Taxation: State and Local, 18 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 767 (1986). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol18/iss2/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Taxation: State and Local Ronald H. Jacobson* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................... 767 II. INCOME TAXATION ................................ 768 A. Unitary Taxation .............................. 768 B. Tax-Exempt Financing......................... 771 C. Interest on Federally GuaranteedBonds ........ 773 III. PROPERTY TAXATION .............................. 776 A. Charitableand EducationalExemptions ........ 776 B. Condominium Assessment Classifications ....... 778 IV. SALES TAXATION - USE TAX EXEMPTION ........ 780 V. TAX PROTESTING .................................. 782 A . Property Tax .................................. 782 B. Retaliatory Tax ................................ 784 VI. LOCAL GOVERNMENT TAXING POWERS ............ 786 A. County Tax Penalty Retention ................. 786 B. Taxation by Home Rule Units ................ -

2021 Revenue Ordinance

2021 Revenue Ordinance As Proposed on December 5, 2019 ii Revenue Ordinance of 2021 to Levy Taxes and Fees and Raise Revenue For the City of Savannah Georgia As adopted on December 18, 2020 Published by City of Savannah Revenue Department Post Office Box 1228 Savannah, GA 31402-1228 CITY OF SAVANNAH 2021 CITY COUNCIL Mayor Van R. Johnson, II Post 1 At-Large Post 2 At-Large Kesha Gibson-Carter Alicia Miller Blakely District 1 District 2 Bernetta B. Lanier Detric Leggett District 3 District 4 Linda Wilder-Bryan Nick Palumbo District 5 District 6 Dr. Estella Edwards Shabazz Kurtis Purtee Revenue Ordinance Compiled By Revenue Director/City Treasurer Ashley L. Simpson Utility Billing Manager Nicole Brantley Treasury Manager Joel Paulk Business Tax & Alcohol License Manager Judee Jones Revenue Special Projects Coordinator Saja Aures Table of Contents Revenue Ordinance of 2021 ....................................................................................................................... 1 ARTICLE A. GENERAL ............................................................................................................................... 1 Section 1. SCOPE; TAXES AND FEES .................................................................................................... 1 Section 2. DEFINITIONS ........................................................................................................................... 1 Section 3. JANUARY 1 GOVERNS FOR YEAR ...................................................................................... -

Transfer Pricing As a Vehicle in Corporate Tax Avoidance

The Journal of Applied Business Research – January/February 2017 Volume 33, Number 1 Transfer Pricing As A Vehicle In Corporate Tax Avoidance Joel Barker, Borough of Manhattan Community College, USA Kwadwo Asare, Bryant University, USA Sharon Brickman, Borough of Manhattan Community College, USA ABSTRACT Using transfer pricing, U.S. Corporations are able to transfer revenues to foreign affiliates with lower corporate tax rates. The Internal Revenue Code requires intercompany transactions to comply with the “Arm’s Length Principle” in order to prevent tax avoidance. We describe and use elaborate examples to explain how U.S. companies exploit flexibility in the tax code to employ transfer pricing and related tax reduction and avoidance methods. We discuss recent responses by regulatory bodies. Keywords: Transfer Pricing; Tax avoidance; Inversion; Tax Evasion; Arm’s Length Principle; R & D for Intangible Assets; Cost Sharing Agreements; Double Irish; Profit Shifting INTRODUCTION ver the last decade U.S. corporations have been increasing their use of Corporate Inversions. In an inversion, corporations move their domestic corporations to foreign jurisdictions in order to be eligible O for much lower corporate tax rates. Furthermore, inversions allow U.S. corporations that have accumulated billions of dollars overseas through transfer pricing to access those funds tax free. With an inversion a U.S. corporation becomes a foreign corporation and would not have to pay tax to the U.S. government to access the funds accumulated abroad as the funds no longer have to be repatriated to be spent. Corporations continue to avoid taxation through Transfer Pricing. This article explains transfer pricing and discusses some of the tax issues that transfer pricing pose including recommendations and proposed legislation to mitigate the practice. -

Panama Papers Leaks

GRAY TOLUB1 LLP Focusing on Domestic & International Taxation, Real Estate, Corporate, and Trust & Estate Matters. Client AlertAPRIL 04, 2016 AUTHORS Armin Gray Benjamin Tolub PANAMA PAPERS LEAKS: SUBJECT THE TAX MAN COMETH OVDP Panama On April 03, 2016, the press reported that 11.5 million records were leaked from Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca. The records detail offshore holdings of the celebrities, politicians, and the mega-rich many of which were purportedly engaged in illegal activities including tax evasion. Such leaks have been referred to as the “Panama papers” or the “Wikileaks of the mega-rich” by some newspapers.1 More details can be found at the website of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (“ICIJ”), which have summarized their findings as follows: The largest cross-border journalism collaboration ever has uncovered a giant leak of documents from Mossack Fonseca, a global law firm based in Panama. The secret files: • Include 11.5 million records, dating back nearly 40 years – making it the largest leak in offshore history. Contains details on more than 214,000 offshore entities connected to people in more than 200 countries and territories. Company owners 1 See Toppo, Greg, “Worldwide, jaws drop to Panama Papers’ Leak”, USA Today, last accessed April 3, 2016, available at: http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/04/03/reactions- panama-papers-leak-go-global/82589874/. www.graytolub.com Client Alert Page 2 in [sic] billionaires, sports stars, drug smugglers and fraudsters. • Reveal the offshore holdings 140 politicians and public officials around the world – including 12 current and former world leaders. -

An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M

TaxingTaxing Simply Simply District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission TaxingTaxing FairlyFairly Full Report District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 550 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 518-7275 Fax: (202) 466-7967 www.dctrc.org The Authors Robert M. Schwab Professor, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Amy Rehder Harris Graduate Assistant, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Authors’ Acknowledgments We thank Kim Coleman for providing us with the assessment data discussed in the section “The Incidence of a Graded Property Tax in the District of Columbia.” We also thank Joan Youngman and Rick Rybeck for their help with this project. CHAPTER G An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M. Schwab and Amy Rehder Harris Introduction In most jurisdictions, land and improvements are taxed at the same rate. The District of Columbia is no exception to this general rule. Consider two homes in the District, each valued at $100,000. Home A is a modest home on a large lot; suppose the land and structures are each worth $50,000. Home B is a more sub- stantial home on a smaller lot; in this case, suppose the land is valued at $20,000 and the improvements at $80,000. Under current District law, both homes would be taxed at a rate of 0.96 percent on the total value and thus, as Figure 1 shows, the owners of both homes would face property taxes of $960.1 But property can be taxed in many ways. Under a graded, or split-rate, tax, land is taxed more heavily than structures. -

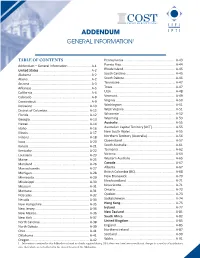

Addendum General Information1

ADDENDUM GENERAL INFORMATION1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pennsylvania ......................................................... A-43 Addendum – General Information ......................... A-1 Puerto Rico ........................................................... A-44 United States ......................................................... A-2 Rhode Island ......................................................... A-45 Alabama ................................................................. A-2 South Carolina ...................................................... A-45 Alaska ..................................................................... A-2 South Dakota ........................................................ A-46 Arizona ................................................................... A-3 Tennessee ............................................................. A-47 Arkansas ................................................................. A-5 Texas ..................................................................... A-47 California ................................................................ A-6 Utah ...................................................................... A-48 Colorado ................................................................. A-8 Vermont................................................................ A-49 Connecticut ............................................................ A-9 Virginia ................................................................. A-50 Delaware ............................................................. -

Download Article (PDF)

5th International Conference on Accounting, Auditing, and Taxation (ICAAT 2016) TAX TRANSPARENCY – AN ANALYSIS OF THE LUXLEAKS FIRMS Johannes Manthey University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany Dirk Kiesewetter University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany Abstract This paper finds that the firms involved in the Luxembourg Leaks (‘LuxLeaks’) scandal are less transparent measured by the engagement in earnings management, analyst coverage, analyst accuracy, accounting standards and auditor choice. The analysis is based on the LuxLeaks sample and compared to a control group of large multinational companies. The panel dataset covers the years from 2001 to 2015 and comprises 19,109 observations. The LuxLeaks firms appear to engage in higher levels of discretionary earnings management measured by the variability of net income to cash flows from operations and the correlation between cash flows from operations and accruals. The LuxLeaks sample shows a lower analyst coverage, lower willingness to switch to IFRS and a lower Big4 auditor rate. The difference in difference design supports these findings regarding earnings management and the analyst coverage. The analysis concludes that the LuxLeaks firms are less transparent and infers a relation between corporate transparency and the engagement in tax avoidance. The paper aims to establish the relationship between tax avoidance and transparency in order to give guidance for future policy. The research highlights the complex causes and effects of tax management and supports a cost benefit analysis of future tax regulation. Keywords: Tax Avoidance, Transparency, Earnings Management JEL Classification: H20, H25, H26 1. Introduction The Luxembourg Leaks (’LuxLeaks’) scandal made public some of the tax strategies used by multinational companies. -

Imports in GST Regime (Goods & Services Tax)

Imports in GST Regime (Goods & Services Tax) Introduction Under the GST regime, Article 269A constitutionally mandates that supply of goods, or of services, or both in the course of import into the territory of India shall be deemed to be supply of goods, or of services, or both in the course of inter-State trade or commerce. So import of goods or services will be treated as deemed inter-State supplies and would be subject to Integrated tax. While IGST on import of services would be leviable under the IGST Act, the levy of the IGST on import of goods would be levied under the Customs Act, 1962 read with the Custom Tariff Act, 1975. The importer of services will have to pay tax on reverse charge basis. However, in respect of import of online information and database access or retrieval services (OIDAR) by unregistered, non-taxable recipients, the supplier located outside India shall be responsible for payment of taxes (IGST). Either the supplier will have to take registration or will have to appoint a person in India for payment of taxes. Supply of goods or services or both to a Special Economic Zone developer or a unit shall be treated as inter-State supply and shall be subject to levy of integrated tax. Directorate General of Taxpayer Services CENTRAL BOARD OF EXCISE & CUSTOMS www.cbec.gov.in Imports in GST Regime (Goods & Services Tax) Importer Exporter Code (IEC): As per DGFT’s Trade Notice No. 09 The taxes will be calculated as under: dated 12.06.2017, the PAN of an entity would be used as the Import Particulars Duty Export code (IEC). -

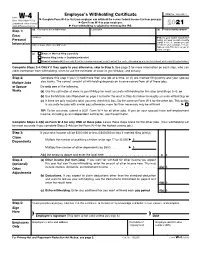

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

Environmental Taxes and Subsidies: What Is the Appropriate Fiscal Policy for Dealing with Modern Environmental Problems?

William & Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review Volume 24 (2000) Issue 1 Environmental Justice Article 6 February 2000 Environmental Taxes and Subsidies: What is the Appropriate Fiscal Policy for Dealing with Modern Environmental Problems? Charles D. Patterson III Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Repository Citation Charles D. Patterson III, Environmental Taxes and Subsidies: What is the Appropriate Fiscal Policy for Dealing with Modern Environmental Problems?, 24 Wm. & Mary Envtl. L. & Pol'y Rev. 121 (2000), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr/vol24/iss1/6 Copyright c 2000 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr ENVIRONMENTAL TAXES AND SUBSIDIES: WHAT IS THE APPROPRIATE FISCAL POLICY FOR DEALING WITH MODERN ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS? CHARLES D. PATTERSON, III* 1 Oil spills and over-fishing threaten the lives of Pacific sea otters. Unusually warm temperatures are responsible for an Arctic ice-cap meltdown. 2 Contaminated drinking water is blamed for the spread of avian influenza from wild waterfowl to domestic chickens.' Higher incidences of skin cancer are projected, due to a reduction in the ozone layer. Our environment, an essential and irreplaceable resource, has been under attack since the industrial age began. Although we have harnessed nuclear energy, made space travel commonplace, and developed elaborate communications technology, we have been unable to effectively eliminate the erosion and decay of our environment. How can we deal with these and other environmental problems? Legislators have many methods to encourage or discourage individual or corporate conduct. -

Biomass Basics: the Facts About Bioenergy 1 We Rely on Energy Every Day

Biomass Basics: The Facts About Bioenergy 1 We Rely on Energy Every Day Energy is essential in our daily lives. We use it to fuel our cars, grow our food, heat our homes, and run our businesses. Most of our energy comes from burning fossil fuels like petroleum, coal, and natural gas. These fuels provide the energy that we need today, but there are several reasons why we are developing sustainable alternatives. 2 We are running out of fossil fuels Fossil fuels take millions of years to form within the Earth. Once we use up our reserves of fossil fuels, we will be out in the cold - literally - unless we find other fuel sources. Bioenergy, or energy derived from biomass, is a sustainable alternative to fossil fuels because it can be produced from renewable sources, such as plants and waste, that can be continuously replenished. Fossil fuels, such as petroleum, need to be imported from other countries Some fossil fuels are found in the United States but not enough to meet all of our energy needs. In 2014, 27% of the petroleum consumed in the United States was imported from other countries, leaving the nation’s supply of oil vulnerable to global trends. When it is hard to buy enough oil, the price can increase significantly and reduce our supply of gasoline – affecting our national security. Because energy is extremely important to our economy, it is better to produce energy in the United States so that it will always be available when we need it. Use of fossil fuels can be harmful to humans and the environment When fossil fuels are burned, they release carbon dioxide and other gases into the atmosphere. -

Commercialization and Deployment at NREL: Advancing Renewable

Commercialization and Deployment at NREL Advancing Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency at Speed and Scale Prepared for the State Energy Advisory Board NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. Management Report NREL/MP-6A42-51947 May 2011 Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. Available electronically at http://www.osti.gov/bridge Available for a processing fee to U.S. Department of Energy and its contractors, in paper, from: U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information P.O. Box 62 Oak Ridge, TN 37831-0062 phone: 865.576.8401 fax: 865.576.5728 email: mailto:[email protected] Available for sale to the public, in paper, from: U.S.