Lessons from Ohio's High-Performing Urban High Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download 1939 Guide

• GV 1195 o 4 i927/28 1939/40 A RECORD that has SPALDING' "RED COVER" SERIES OF ArHI,ETIC HAXDIlOOKS never been equalled I No. 429 r National Collegiate l Athletic Association PALDING is proud of t~e fact that it has not only S kept pace with sport 1Il America, but that it has made-and cOil/illlteJ to make-material contribu Wrestling Rules tions to its developmen t. 1938-1939 • S p aldi n g ha s outfitled • The Spalding Oflieial Na every U. S. Olympic Tn"'k t ion'll League Baseball has As Recommended by the Rules Committee ,,,,,I Field Team sinl'e the heen the one and only ball consisting of revival of the Olympic games used hy the National League DR. R. G. CLAPP, Chairman University of Nebraska in J396. for over 50 years. DR. ]. A. ROCKWELL, Secretary . Mass. Inst. Tech. C. P. MILES Virginia Polytechnic Institute • Spalding produeed the • Spalding produced the E. G. SCHROEDER State University of Iowa first golf ball eVel" made in first football ever made in C. F. FOSTER. ... ... Princeton this country. this country. J. W. HANCOCK. Colorado State College of Education B. E. WIGGINS . Columbus (Ohio) Public Schools Representative of National High School Federation • Spalding produced the • Every long pass reeorded first golf duhs ever made in has been made with a Spald Advisory Committee this eountry. ing Official Football. First District.. R. K. COLE (Brown) Second District , W. AUSTIN BISHOP (Pennsylvania) • Spalding or i g inat ed • Every record kick has Third District . LIEUT.COL.H,M. -

EAST Sideny NEWS

SPORTS MENU TIPS Celebrate MLKDay EAST SIDEny NEWS A Delicious Twist ISSUED TUESDAY AND FRIDAY Willie Pastrano January 19, 1998 On The Traditional Dies At 62 SeePag~4 SERVING LARCHMERE- WOODLAND, SHAKER SQUARE, BUCKEYE, WOODLAND, MT. PLEASANT, LEE & AVALON, HARVARD - LEE, MILES - UNION, UNIVERSITY See page 7 CIRCLE AREA, WARRENSVILLE HEIGHTS, VILLAGE OF FREE - HIGHLAND HILLS AND EAST CLEVELAND George Fraser publishes READ ON • WRITE ON Thesday, January 6, 1998- Friday, January 9, 1998 'Race For Success' book Though born pooG guide packed with tools, tips, When Earle B. Turner is toric significance of this position history this past November, and black and one of nine children in contacts, and techniques in sworn in as Clerk of Courts of in the state of Ohio. thus is the first to be sworn in to Brooklyn, New York, George structing black America how to the Cleveland Municipal Court Turner, a 44 year- old hold this office. Fraser learned at an early age to do well while also doing good. on Friday (Jan. 9), at I :OOp.m. in Democrat, became the first Afri ''It is with a deep sense importances of a persistent, posi Fraser believes that for Cleveland City Council Cham can- American to be elected to of pride for African- Americans tive attitude from a family that those subscribing to the new Fraser bers, the event will take on his- this prestigious office in the Ohio in Cleveland and throughout our shunned the "dependency men black mantra of vertical network tality" and the "doomed to fail" ing - reaching down and lifting attitude. -

Polling Locations March 17, 2020 Presidential Primary Election

Polling Locations March 17, 2020 Polling Location Street AddressPresidential Primary ElectionCity Zip Code Precinct ABRAHAM LINCOLN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 6009 DUNHAM ROAD MAPLE HTS 44137 MAPLE HEIGHTS -01-A ABRAHAM LINCOLN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 6009 DUNHAM ROAD MAPLE HTS 44137 MAPLE HEIGHTS -01-B ABRAHAM LINCOLN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 6009 DUNHAM ROAD MAPLE HTS 44137 MAPLE HEIGHTS -02-A ABRAHAM LINCOLN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 6009 DUNHAM ROAD MAPLE HTS 44137 MAPLE HEIGHTS -02-B ABRAHAM LINCOLN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 6009 DUNHAM ROAD MAPLE HTS 44137 MAPLE HEIGHTS -03-A ADLAI STEVENSON PRE K-8 SCHOOL 18300 WODA AVENUE CLEVELAND 44122 CLEVELAND -01-L ADLAI STEVENSON PRE K-8 SCHOOL 18300 WODA AVENUE CLEVELAND 44122 CLEVELAND -01-M ADLAI STEVENSON PRE K-8 SCHOOL 18300 WODA AVENUE CLEVELAND 44122 CLEVELAND -01-N ADLAI STEVENSON PRE K-8 SCHOOL 18300 WODA AVENUE CLEVELAND 44122 CLEVELAND -01-P ADLAI STEVENSON PRE K-8 SCHOOL 18300 WODA AVENUE CLEVELAND 44122 CLEVELAND -01-Q ADLAI STEVENSON PRE K-8 SCHOOL 18300 WODA AVENUE CLEVELAND 44122 CLEVELAND -01-S ADVENT LUTHERAN CHURCH SOLON 5525 HARPER ROAD SOLON 44139-1828 SOLON -05-A ADVENT LUTHERAN CHURCH SOLON 5525 HARPER ROAD SOLON 44139-1828 SOLON -05-B ALBERT BUSHNELL HART ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 3900 EAST 75TH STREET CLEVELAND 44105 CLEVELAND -12-F ALBERT BUSHNELL HART ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 3900 EAST 75TH STREET CLEVELAND 44105 CLEVELAND -12-G ALBERT BUSHNELL HART ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 3900 EAST 75TH STREET CLEVELAND 44105 CLEVELAND -12-H ALBERT BUSHNELL HART ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 3900 EAST 75TH STREET CLEVELAND 44105 CLEVELAND -12-I ALBION -

2011 Annual Report

2011 Mayor’s Annual Report City of Cleveland Frank G. Jackson, Mayor November 2012 Table of Contents Mayor’s Letter……………………………………………………v Introduction ………………………………………………………vii Development Cluster Building & Housing…………………………….. 3 City Planning…...………………………………… 7 Community Development……………………….… 11 Economic Development………………….…..….… 17 Port Control………………..……………………... 21 Operations Cluster Office of Capital Projects………………………... 29 Public Utilities…………………………………….. 33 Public Works……………………………………... 39 Public Affairs Cluster Aging………….………………………………… 49 Civil Service……………………..………………. 55 Community Relations Board……..…..…………… 57 Human Resources …………………… 63 Office of Equal Opportunity……………………... 69 Public Health……………………………………... 73 Workforce Investment Board……………………... 79 Public Safety Administration ……………………………………. 83 Animal Control Services..…………………………. 87 Correction………………………………………… 91 Emergency Medical Service………..………….….. 95 Fire……………………………………..………… 99 Police………………………………………….…. 103 Sustainability …………………………………………………. 109 Finance ……………………………………………..………….. 117 Education ……………………………………………………. 125 Law………………………………………………….…….….… 139 Citizen’s Guide/Index………………………….………….… 143 2011 Mayor’s Annual Report User Guide Department John Smith, Director __________________________________________________________ Key Public Service Areas Critical Objectives Assist Seniors in accessing Help seniors avoid becoming victims of services, benefits and programs predatory lenders and scam contractors and to enhance their quality of life avoid citations for housing -

Yearbook Title) City Years

Ohio Genealogical Society Yearbook Collection PRINTED 7/17/2020 School names in blue and underlined are hyperlinked to yearbooks available online on an external website. ` School Name (Yearbook Title) City Years Ada High School (Watchdog) Ada [SR11w] 1940 Ada High School (We) Ada [SR11w] 1941-42, 1963, 1987, 2012-13, 2017 Ohio Northern University Ada [SR3n] 1918, 1920, 1923-32, 1934-38, 1940-42, 1946-51, 1953-57, 1959-64, 1967-69, 1971-85, 1987-97, 2000-02, 2006-08, (Northern) 2011, 2013-14 Adario High School (Hi-Lites) Adario [SR19h] 1933 Fulton Township School Ai [SR959f] 1949, 1955-56, 1960 (Fultonian) Symmes Valley High School Aid [SR65v] 2009-19 (Viking) Archbishop Hoban High School Akron [SR651w] 1957-58, 1961-63, 1966-70, 1980, 1983-84, 1986, 1989-92, 1994-95, 1997, 1999-2012 (Way) Buchtel College (Buchtel) Akron [SR3b] 1908 Buchtel College (Tel-Buch) Akron [SR3t] 1911 Buchtel High School (Griffin) Akron [SR854g] Jun 1940, Jun 1941, Jun 1942, Jun 1943, Jun 1944, Jan 1945, Jun 1945, Jun 1946, Jan 1947, Jun 1947, Jan 1948, Jun 1948, Jan 1949, Jun 1949, Jan 1950, Jun 1950, Jan 1951, Jun 1951, Jan 1952, Jun 1952, Jan 1953, Jun 1953, 1954-69, 1986, 1988-89, 1991-93, 1995-99, 2003, 2015-17 Central High School (Central Akron [SR333c] JUNE 1951 Forge) Central High School (Wildcat) Akron [SR333w] 1958, 1961, 1964-65, 1968-70 Central – Hower (Artisan) Akron [SR333a] 1971-76, 1978-79, 1981-82, 1984, 1988-89, 1993, 1998-99, 2006 East High School (Magic Carpet) Akron [SR77m] 1926 Page 1 Ohio Genealogical Society Yearbook Collection PRINTED 7/17/2020 -

Invitation to Bid #21296

INVITATION TO BID #21296 For John Hay High School Asbestos Containing Material Gymnasium Floor Removal FOR THE CLEVELAND MUNICIPAL SCHOOL DISTRICT DBA: CLEVELAND METROPOLITAN SCHOOL DISTRICT BOARD OF EDUCATION, 1111 SUPERIOR AVENUE E, SUITE 1800 CLEVELAND, OHIO 44114 UNDER THE DIRECTION OF TRADES DEPARTMENT OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CLEVELAND METROPOLITAN SCHOOL DISTRICT - CUYAHOGA COUNTY, OHIO Table of Contents Part I: NOTICE OF INVITATION TO BID #21296 ....................................................................................... 3 Section I: Instructions to Bidders ...................................................................................................................... 4 Required Purchasing Division Documents and Instructions ............................................................................. 8 Section I: Addendum Acknowledgement Form for ITB #21296 ...................................................................... 9 Section II: Acknowledgement ......................................................................................................................... 10 Section III: Vendor Request Form .................................................................................................................. 11 Section IV: Taxpayer ID Form ....................................................................................................................... 12 Section V: No Proposal Form ........................................................................................................................ -

Annual Report

July 1, 2007–June 30, 2008 AnnuAl RepoRt 1 Contents 3 Board of Trustees 4 Trustee Committees 7 Message from the Director 12 Message from the Co-Chairmen 14 Message from the President 16 Renovation and Expansion 24 Collections 55 Exhibitions 60 Performing Arts, Music, and Film 65 Community Support 116 Education and Public Programs Cover: Banners get right to the point. After more than 131 Staff List three years, visitors can 137 Financial Report once again enjoy part of the permanent collection. 138 Treasurer Right: Tibetan Man’s Robe, Chuba; 17th century; China, Qing dynasty; satin weave T with supplementary weft Prober patterning; silk, gilt-metal . J en thread, and peacock- V E feathered thread; 184 x : ST O T 129 cm; Norman O. Stone O PH and Ella A. Stone Memorial er V O Fund 2007.216. C 2 Board of Trustees Officers Standing Trustees Stephen E. Myers Trustees Emeriti Honorary Trustees Alfred M. Rankin Jr. Virginia N. Barbato Frederick R. Nance Peter B. Lewis Joyce G. Ames President James T. Bartlett Anne Hollis Perkins William R. Robertson Mrs. Noah L. Butkin+ James T. Bartlett James S. Berkman Alfred M. Rankin Jr. Elliott L. Schlang Mrs. Ellen Wade Chinn+ Chair Charles P. Bolton James A. Ratner Michael Sherwin Helen Collis Michael J. Horvitz Chair Sarah S. Cutler Donna S. Reid Eugene Stevens Mrs. John Flower Richard Fearon Dr. Eugene T. W. Sanders Mrs. Robert I. Gale Jr. Sarah S. Cutler Life Trustees Vice President Helen Forbes-Fields David M. Schneider Robert D. Gries Elisabeth H. Alexander Ellen Stirn Mavec Robert W. -

Judicial Candidates Rating Coalition Request for Biographical Information from Judicial Candidates

JUDICIAL CANDIDATES RATING COALITION REQUEST FOR BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION FROM JUDICIAL CANDIDATES This form seeks information about you that will be posted on the Judge4Yourself.com website with its ratings. Please complete and return this form and a color photograph of yourself before your scheduled interview. Each Candidate is responsible to provide accurate information, to review the information when posted and to advise the JCRC promptly of any correction required to that candidate’s posted information. Name: JAMES W. SATOLA Current City of Residence: University Heights, Ohio Date and Place of Birth: August 26, 1961 (Cleveland, Ohio) Undergraduate School and Degree (Year of Graduation): The Ohio State University, B.S., Zoology (1984) Law School (Year of Graduation): Case Western Reserve School of Law, Juris Doctor (1989) Other Graduate School, if any, and Degree (Year of Graduation): Harvard Program on Negotiation, Certificate (2017) Year Admitted to Practice in Ohio: 1989 Number of Years Engaged in Practice of Law in Ohio 31 years (excluding Judicial Service) Other Court(s) to Which You Are Admitted & Year(s): District of Columbia (1991); Supreme Court of the United States (1993); United States Courts of Appeals for the Armed Forces (2009), Second Circuit (2006), Sixth Circuit (1992), Seventh Circuit (2011), Eighth Circuit (2001), Ninth Circuit (2004), Eleventh Circuit (2017); United States District Courts for the District of Arizona (1997), Northern District of Ohio (1990), Southern District of Ohio (2007). Number of Years Engaged in Practice of Law in any State (excluding Judicial Service): 31 years Briefly describe your areas of practice: General Civil Litigation Practice, Self-Employed (2011-Present), and with Squire, Sanders & Dempsey L.L.P. -

Cleveland Metropolitan School District Human Ware Audit: Findings and Recommendations

Cleveland Metropolitan School District Human Ware Audit: Findings and Recommendations AUGUST 14, 2008 Submitted To: Eugene T.W. Sanders, Ph.D. Chief Executive Officer Cleveland Metropolitan School District 1380 East 6th Street Cleveland, OH 44114 Prepared By: American Institutes for Research® 1000 Thomas Jefferson Street, NW Washington, DC 20007-3835 Authors: David Osher, Ph.D. Jeffrey M. Poirier, M.A. Kevin P. Dwyer, M.A., NCSP Regenia Hicks, Ph.D. Leah J. Brown, B.A. Stephanie Lampron, M.A. Carlos Rodriguez, Ph.D Cleveland Metropolitan School District Human Ware Audit ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The report authors express appreciation for the thoughtful input of the AIR senior staff members who have contributed to the work, including Dr. Libi Gil; Dr. Jennifer O’Day; Ms. Maria Guasp, M.S.; and Ms. Sandra Keenan, M.Ed. We also acknowledge the contributions of other AIR staff, including Dr. Sarah Jones, who supported the review of qualitative data; Drs. Kimberly Kendziora and Lorin Mueller as well as numerous staff in AIR’s Assessment Program who assisted with various activities related to the Conditions for Learning survey; and Mr. Phil Esra and Ms. Holly Baker, who assisted with report editing and formatting. We recognize Cleveland Mayor Frank G. Jackson and Dr. Eugene Sanders, chief executive officer of the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (the District), for their commitment to not limiting the scope of the Human Ware Audit activities and to a systemic approach to the recommendations. We are also very grateful to the support of the District’s chief academic officer, Mr. Eric Gordon; his staff, including the District’s research team; and the mayor’s staff (in particular, Ms. -

2020 Annual Report

The Future of ACE Electrician CADD Instructor Architect Civil Engineer Urban Planner Construction Manager ACE MENTOR PROGRAM CLEVELAND AFFILIATE ACE MENTOR PROGRAM ARCHITECTURE CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING 2020 Annual Report acecleveland.org Letters from Leadership To say this past year has been unusual is an understatement. Unfortunately, our 2019- 20 program was cut short due to the COVID pandemic but we did have some silver linings. ACE Cleveland distributed $122,000 dollars in scholarships to 14 very deserving students. Most notably, one of Cleveland’s own, Diego Cortez, was awarded the ACE National CMiC—Allen Berg Memorial Scholarship for $40,000. We are very proud of Diego and this great accomplishment. A huge kudos needs to go to all the mentors and teachers that continue to foster this program during the shutdown. They are the lifeline that has kept the students engaged. I would also like to recognize the ACE Board for their unwavering dedication to bring an Mark Panzica after-school program to this year’s students in a remote environment. The Board also BOARD CHAIR re-evaluated the strategic plan and refined our goals to be more impactful and equitable. This process has helped us focus on how we can provide better opportunities to the students we serve. As we continue to navigate through a remote learning environment, our focus remains the same, which is to Engage, Excite, and Enlighten the students in the A / C / E industry and help foster their growth beyond high school graduation. I’m very proud of the impact ACE Mentor Cleveland has had and the progress we continue to make. -

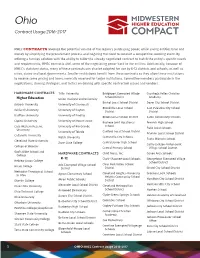

Ohio Contract User List 2016-2017

Ohio Contract Usage 2016-2017 MHEC CONTRACTS leverage the potential volume of the region’s purchasing power, while saving entities time and money by simplifying the procurement process and negating the need to conduct a competitive sourcing event. By offering a turnkey solution with the ability to tailor the already negotiated contract to match the entity’s specific needs and2 requirements,0162017 MHEC contracts shift some of the negotiating power back to the entities. Additionally, because of MHEC’s statutory status, many of these contracts can also be adopted for use by K-12 districts and schools, as well as cities, states and local governments. Smaller institutions benefit from these contracts as they allow these institutions to receive some pricing and terms normally reserved for larger institutions. Committee members participate in the negotiations, sharing strategies, and tactics on dealing with specific contractual issues and vendors. ANNUAL HARDWARE CONTRACTS Tiffin University Bridgeport Exempted Village Cuyahoga Valley Christian School District Academy Higher Education Union Institute and University REPORT Bristol Local School District Dover City School District Antioch University University of Cincinnati Brookville Local School East Palestine City School Ashland University University of Dayton to the Member States District District Bluffton University University of Findlay Brown Local School District Eaton Community Schools Capital University University of Mount Union Buckeye Joint Vocational Fenwick High School Case Western Reserve University of Rio Grande School Field Local Schools University University of Toledo Canfield Local School District Franklin Local School District Cedarville University Walsh University Centerville City Schools Fuchs Mizrachi School Cleveland State University Zane State College Central Junior High School Gallia-Jackson-Vinton Joint College of Wooster Central Primary School Village School District God’s Bible School and HARDWARE CONTRACTS Child Focus, Inc. -

Location List by City Ward Precinct

Polling Location List Page 1 of 70 Election Date: November 03, 2020 Report Date: 9/30/2020 8:59:54AM BAYVILLAGE BAY VILLAGE -01 A BAY PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, 25415 LAKE ROAD, 44140-2624 B BAY PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, 25415 LAKE ROAD, 44140-2624 C BAY PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, 25415 LAKE ROAD, 44140-2624 BAY VILLAGE -02 A BAY VILLAGE MIDDLE SCHOOL, 27725 WOLF ROAD, 44140 B BAY PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, 25415 LAKE ROAD, 44140-2624 C BAY VILLAGE MIDDLE SCHOOL, 27725 WOLF ROAD, 44140 BAY VILLAGE -03 A BAY UNITED METHODIST CHURCH, 29931 LAKE ROAD, 44140 B BAY UNITED METHODIST CHURCH, 29931 LAKE ROAD, 44140 C BAY UNITED METHODIST CHURCH, 29931 LAKE ROAD, 44140 BAY VILLAGE -04 A ST BARNABAS EPISCOPAL CHURCH, 468 BRADLEY ROAD, 44140 B ST BARNABAS EPISCOPAL CHURCH, 468 BRADLEY ROAD, 44140 C ST BARNABAS EPISCOPAL CHURCH, 468 BRADLEY ROAD, 44140 12 Polling Location List Page 2 of 70 Election Date: November 03, 2020 Report Date: 9/30/2020 8:59:54AM BEACHWOOD BEACHWOOD -00 A HILLTOP ELEMENTARY SCHOOL, 24524 HILLTOP DRIVE, 44122-1344 B BEACHWOOD HIGH SCHOOL, 25100 FAIRMOUNT BOULEVARD, 44122-2250 C BEACHWOOD HIGH SCHOOL, 25100 FAIRMOUNT BOULEVARD, 44122-2250 D BRYDEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL, 25501 BRYDEN ROAD, 44122-4162 E BRYDEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL, 25501 BRYDEN ROAD, 44122-4162 F BEACHWOOD HIGH SCHOOL, 25100 FAIRMOUNT BOULEVARD, 44122-2250 G HILLTOP ELEMENTARY SCHOOL, 24524 HILLTOP DRIVE, 44122-1344 H BEACHWOOD HIGH SCHOOL, 25100 FAIRMOUNT BOULEVARD, 44122-2250 I BEACHWOOD HIGH SCHOOL, 25100 FAIRMOUNT BOULEVARD, 44122-2250 9 Polling Location List Page 3 of 70 Election Date: