Graffiti Protection Protocol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning Commission March 27, 2018 at 6:00 P.M. City Hall – Boards and Commissions Room 301 W

Planning Commission March 27, 2018 at 6:00 P.M. City Hall – Boards and Commissions Room 301 W. 2nd Street Austin, TX 78701 Greg Anderson Patricia Seeger Conor Kenny James Shieh – Secretary Fayez Kazi – Vice-Chair Jeffrey Thompson Karen McGraw Trinity White Tom Nuckols Todd Shaw Stephen Oliver – Chair William Burkhardt – Ex-Officio Angela De Hoyos Hart Richard Mendoza – Ex-Officio James Schissler – Parliamentarian Ann Teich – Ex-Officio EXECUTIVE SESSION (No public discussion) The Planning Commission will announce it will go into Executive Session, if necessary, pursuant to Chapter 551 of the Texas Government Code, to receive advice from Legal Counsel on matters specifically listed on this agenda. The Commission may not conduct a closed meeting without the approval of the city attorney. Private Consultation with Attorney – Section 551.071 A. CITIZEN COMMUNICATION The first four (4) speakers signed up prior to the meeting being called to order will each be allowed a three-minute allotment to address their concerns regarding items not posted on the agenda. B. APPROVAL OF MINUTES 1. Approval of minutes from March 13, 2018. Facilitator: Rosemary Avila, 512-974-2784 C. PUBLIC HEARINGS 1. Plan Amendment: NPA-2017-0018.01 - Burnet Lane; District 7 Location: 2106 and 2108 Payne Avenue & 6431 Burnet Lane, Shoal Creek Watershed, Brentwood/Highland Combined NP Area Owner/Applicant: ARCH Properties Inc., Trustee Agent: Drenner Group (Amanda Swor) Request: Single Family and Mixed Use/Office land use to Mixed Use land use Staff Rec.: Pending. Staff postponement request to May 8, 2018. Staff: Maureen Meredith, 512-974-2695 Planning and Zoning Department 2. -

A Ustin , Texas

PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS $26.95 austin, texas austin, Austin, Texas Austin,PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS Texas PUBLISHERS A Photographic Portrait Since its founding in 1839, Austin Peter Tsai A Photographic Portrait has seen quite a bit of transformation Peter Tsai is an internationally published over the years. What was once a tiny photographer who proudly calls Austin, frontier town is today a sophisticated Texas his home. Since moving to Austin urban area that has managed to main- in 2002, he has embraced the city’s natu- PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTStain its distinctive,PUBLISHERS offbeat character, ral beauty, its relaxed and open-minded and indeed, proudly celebrates it. attitude, vibrant nightlife, and creative The city of Austin was named for communities. In his Austin photos, he Stephen F. Austin, who helped to settle strives to capture the spirit of the city the state of Texas. Known as the “Live he loves by showcasing its unique and A P Music Capital of the World,” Austin har- eclectic attractions. H bors a diverse, well-educated, creative, Although a camera is never too far O PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS and industrious populace. Combined T away, when he is not behind the lens, OGR with a world-class public university, you can find Peter enjoying Austin with APH a thriving high-tech industry, and a his friends, exploring the globe, kicking laid-back, welcoming attitude, it’s no a soccer ball, or expanding his culinary IC POR wonder Austin’s growth continues un- palate. abated. To see more of Peter’s photography, visit T From the bracing artesian springs to R www.petertsaiphotography.com and fol- PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTSA PUBLISHERS PROPERTY OF TWINLIGHTS PUBLISHERS I the white limestone cliffs and sparkling low him on Twitter @supertsai. -

National Register of Historic Places REGISTRATION FORM NPS Form 10-900 OMB No

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National RegisterSBR of Historic Places Registration Draft Form 1. Name of Property Historic Name: West Fifth Street Bridge at Shoal Creek Other name/site number: National Bridge Inventory (NBI) 142270B00015001 Name of related multiple property listing: NA 2. Location Street & number: West Fifth Street at Shoal Creek City or town: Austin State: Texas County: Travis Not for publication: Vicinity: 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following levels of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D State Historic Preservation Officer ___________________________ Signature of certifying official / Title Date Texas Historical Commission State or Federal agency / bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. _______________________________________________________________________ ___________________________ Signature of commenting or other official -

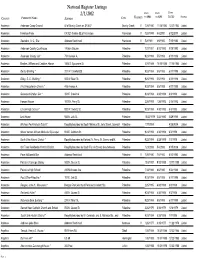

National Register Listings 2/1/2012 DATE DATE DATE to SBR to NPS LISTED STATUS COUNTY PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY VICINITY

National Register Listings 2/1/2012 DATE DATE DATE TO SBR TO NPS LISTED STATUS COUNTY PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY VICINITY AndersonAnderson Camp Ground W of Brushy Creek on SR 837 Brushy Creek V7/25/1980 11/18/1982 12/27/1982 Listed AndersonFreeman Farm CR 323 3 miles SE of Frankston Frankston V7/24/1999 5/4/2000 6/12/2000 Listed AndersonSaunders, A. C., Site Address Restricted Frankston V5/2/1981 6/9/1982 7/15/1982 Listed AndersonAnderson County Courthouse 1 Public Square Palestine7/27/1991 8/12/1992 9/28/1992 Listed AndersonAnderson County Jail * 704 Avenue A. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonBroyles, William and Caroline, House 1305 S. Sycamore St. Palestine5/21/1988 10/10/1988 11/10/1988 Listed AndersonDenby Building * 201 W. Crawford St. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonDilley, G. E., Building * 503 W. Main St. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonFirst Presbyterian Church * 406 Avenue A Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonGatewood-Shelton Gin * 304 E. Crawford Palestine9/23/1994 4/30/1998 6/3/1998 Listed AndersonHoward House 1011 N. Perry St. Palestine3/28/1992 1/26/1993 3/14/1993 Listed AndersonLincoln High School * 920 W. Swantz St. Palestine9/23/1994 4/30/1998 6/3/1998 Listed AndersonLink House 925 N. Link St. Palestine10/23/1979 3/24/1980 5/29/1980 Listed AndersonMichaux Park Historic District * Roughly bounded by South Michaux St., Jolly Street, Crockett Palestine1/17/2004 4/28/2004 Listed AndersonMount Vernon African Methodist Episcopal 913 E. -

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 2014

National Register of Historic Places 2014 Weekly Lists National Register of Historic Places 2014 Weekly Lists ................................................................................ 1 January 3, 2014 ......................................................................................................................................... 3 January 10, 2014 ....................................................................................................................................... 9 January 17, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 16 January 24, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 24 January 31, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 29 February 7, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 34 February 14, 2014 ................................................................................................................................... 37 February 21, 2014 ................................................................................................................................... 43 February 28, 2014 .................................................................................................................................. -

100004750.Pdf

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places REGISTRATION FORM NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 West Fifth Street Bridge at Shoal Creek, Austin, Travis County, Texas 5. Classification Ownership of Property Private X Public - Local Public - State Public - Federal Category of Property building(s) district site X structure object Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 0 0 buildings 0 0 sites 1 0 structures 0 0 objects 1 0 total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 0 6. Function or Use Historic Functions: Transportation: Road-related=bridge Current Functions: Transportation: Road-related=bridge 7. Description Architectural Classification: Other: cantilever concrete girder bridge Principal Exterior Materials: Concrete Narrative Description (see continuation sheets 7-6 through 7-7) Page 2 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places REGISTRATION FORM NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 West Fifth Street Bridge at Shoal Creek, Austin, Travis County, Texas 8. Statement of Significance Applicable National Register Criteria X A Property is associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history. B Property is associated with the lives of persons significant in our past. X C Property embodies the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction or represents the work of a master, or possesses high artistic values, or represents a significant and distinguishable entity whose components lack individual distinction. D Property has yielded, or is likely to yield information important in prehistory or history. -

German Heritage Walking/Driving Tour Downtown Austin, Texas

German Heritage Walking/Driving Tour Downtown Austin, Texas Saengerfest (statewide singing contest), Austin 1889 Willkommen! Explore Texas’ German Heritage in Austin The first concerted effort to bring German settlers to Texas came in 1831, when Johann Friedrich Ernst (aka Friedrich Dirks), from the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg, received a grant of more than 4,000 acres in Stephen F. Austin’s colony. He and his family were on a ship from New York to New Orleans and planned to move to Missouri, but changed their destination when they learned of favorable conditions in Texas. Within a generation, a wide swath of the state from the coastal plain to the Hill Country included dozens of German-settled towns; later generations of Germans also settled in North Texas. Many of these place names, including New Ulm, Frelsburg, Bleiblerville, Oldenburg, Weimar, Schulenburg, Gruene, New Braunfels, Boerne, Fredericksburg and Luckenbach, still dot the map today. There are many examples of German heritage still visible on the Texas landscape, from dance halls and shooting clubs to churches and schools. This walking tour takes you through downtown Austin and the Capitol Complex area, highlighting historic German homes and businesses, some still vibrant and some long passed to modern development. The Texas Historical Commission hopes you will take this opportunity to celebrate the generations of German immigrants who have helped shape the state of Texas. Learn about other German- Texan heritage sites across the state at texashistoryapp.com Stops along the tour route. 1. Turner Hall 11. Kreisle Building 2. Bertram Store 12. J.P. Schneider Store 3. -

Fall 2020 H Volume 24 No. 2 Continued on Page 3 S We Celebrate Sixty Years of Our Preservation Merit Awards Program, We're Gr

Fall 2020 h Volume 24 No. 2 A s we celebrate sixty years of our video shorts that bring these buildings professionals from the preservation, Preservation Merit Awards program, to life through pictures and narration design, and nonprofit worlds who we’re grateful to our 2020 recipients for (@preservationaustin on Facebook and together selected exemplary projects bringing together so much of what we love Instagram). with real community impact: Erin about Austin – iconic brands investing in Dowell, Senior Designer, Lauren Ramirez local landmarks, modest buildings restored During these uncertain times it’s more Styling & Interiors; Melissa Ayala, with big impact, homeowners honoring important than ever to celebrate these Community Engagement & Government the legacies of those who came before, places and their stories, past and Relations Manager, Waterloo Greenway and community efforts that celebrate our present. Thank you for your membership Conservancy; Murray Legge, FAIA, Murray shared heritage. These projects represent and for your continued support – you Legge Architecture; Elizabeth Porterfield, what historic preservation looks like in the make all of this important work possible. Senior Architectural Historian, Hicks & 21st century. We hope you’ll enjoy learning Company; and Justin Kockritz, Lead about them as much as we did, and that Many thanks to our incredible 2020 Project Reviewer, Federal Programs, Texas you’ll follow us on social media for special Preservation Merit Awards Jury, including Historical Commission. Continued on page 3 HILL COUNTRY DECO: LECTURE 2020-2021 Board of Directors Thursday, November 12 7pm to 8:15pm Free, RSVP Required Virtual/Zoom h EXECUTIVE coMMITEE h Using vibrant original photography and historic images, authors Clayton Bullock, President Melissa Barry, VP David Bush and Jim Parsons will trace the history and evolution of Allen Wise, President-Elect Linda Y. -

Historic Road Infrastructure of Texas, 1866-1965

NPS Form 10-900-b United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10- 900-a) . Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Road Infrastructure of Texas, 1866-1965 B. Associated Historic Contexts Development of Texas Road Networks, 1866-1965 Historic Bridges of Texas, 1866-1965 C. Form Prepared bv NAME/TITLE: Bruce Jensen, Historical Studies Supervisor Texas Department of Transportation, Environmental Affairs Division 1 STREET & NUMBER: 125 East 11 h Street TELEPHONE: (512) 416-2628 CITY/TOWN: Austin STATE: Texas ZIP CODE: 78757 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. (_ See continuation sheet for additional comments .) · {SHPO, Texas Historical Commission) ate I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Shoal Creek Trail: Vision to Action Plan

SHOAL CREEK TRAIL: VISION TO ACTION PLAN NOVEMBER 7, 2018 June 1, 2018 On behalf of the Shoal Creek Conservancy Board of Directors, staff, and dedicated volunteers, I am pleased to share the Shoal Creek Trail: Vision to Action Plan. This community-initiated and community-developed Plan presents a bold vision for the future of Austin’s oldest hike-and-bike trail and our city’s growing trail network. It is the result of a yearlong public process facilitated in partnership with the City of Austin Public Works Department. A diverse set of stakeholders guided development of the Plan: the 60+ member Community Advisory Group, the Technical Advisory Group comprised of more than 10 public entities, and a team of skilled consultants. The Plan proposes improvements to the existing 3.9 mile Shoal Creek Trail, as well as a 9+ mile trail extension. When complete, the Shoal Creek Trail will extend for 13 miles from the Butler Trail at Lady Bird Lake to the Northern Walnut Creek Trail north of Highway 183. It will provide a continuous pathway for runners, walkers and cyclists from downtown past the Domain. The Trail will not only connect schools, businesses, neighborhoods and other major destinations, but will also enhance the natural environment and celebrate our city’s cultural heritage along the way. Ultimately, the Trail will become part of become part of “The Big Loop Trail,” a 30-mile loop of urban trail that will traverse Austin by way of creeks and parks. While the Plan presents a sweeping vision for the Shoal Creek Trail, it also embraces a concrete and resourceful approach to achieving this vision. -

Downtown Doorsteps Martin Luther King Jr SELF-GUIDED TOUR

Downtown Doorsteps Martin Luther King Jr SELF-GUIDED TOUR 3 FEATURED HOMES 18th 1. 709 Rio Grande Street E 2. 1310 San Antonio Street r e 3. Cambridge Tower v i D R 16th 4. 706 Congress Avenue d e 5. Brown Building R 15th C F POINTS OF INTEREST 14th A. Sampson-Nalle House BIKE ROUTE B. Pease Elementary School PROVIDED BY 2 G 13th C. Moonlight Tower Sh oa D. Bertram Building l C re e E. Scottish Rite Theater k 12th F. Texas Chili Parlor B H G. The Cloak Room 11th H. Westgate Tower I. e Heman Marion Sweatt Travis County Courthouse d A I I - n 10th 3 J. Austin History Center a 5 r G K. Bremond Block io R 9th L. The Driskill M. Paramount Theatre t J s 8th N. Walter Tips Building e W N O. O. Henry Hall 1 K 5 M 7th P. Republic Square 4 Q. West Sixth Street Bridge Q L 6th O Presented by 5th ii. P 4th NATIONAL REGISTER r s o s i a s o n e z HISTORIC DISTRICTS m o o r a t d a r g e n a L B n r i. Congress Avenue p A a o o u l n l C o c a a a ii. Sixth Street C v S d a a L u Cesar Chavez G i. k e e r C r e l l a W 2020 PRESERVATION AUSTIN SELF-GUIDED HOMES TOUR Downtown Doorsteps: Self-Guided Tour This self-guided tour is a companion piece to Downtown Doorsteps: Preservation Austin’s 2020 Virtual Homes Tour. -

Biennial Report Thcbien16c Thcbiennial04ec 11/8/16 12:08 PM Page 2

THCBien16c_THCBiennial04Ec 11/8/16 12:08 PM Page 1 To protect and preserve the state’s historic and prehistoric resources for the use, education, enjoyment, and economic benefit of present and future generations. Young Texans learn about the Army’s 19th-century Camel Corps at the THC’s Fort Lancaster State Historic Site. 2015/2016 Biennial Report THCBien16c_THCBiennial04Ec 11/8/16 12:08 PM Page 2 Workers restore the historic Franklin County Courthouse clock. Photo: Mount Vernon Optic-Herald THCBien16c_THCBiennial04Ec 11/8/16 12:08 PM Page 1 J LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Lately, you don't have to look too hard to see how popular Texas history and our historic places are to the world. Millions watched “Texas Rising,” an entertaining depiction of the post-Alamo Texas Revolution. While not historically satisfying, the miniseries demonstrated the audience for dramatizations of Texas history—even those filmed in Mexico. A more acclaimed series, “The Leftovers,” filmed on location in Lockhart, showcasing the restored Caldwell County Courthouse. HBO featured the courthouse prominently in the show and its promotions. In Bexar County, the San Antonio Missions received World Heritage Site designation, allowing Texas to tap a global network of cultural tourists. It draws even more international visitors to San Antonio, already a top heritage travel destination. The lesson is clear—Texas history isn’t dead words in dusty volumes, or old buildings falling into decay. Texas history is alive, inspiring and fascinating audiences as much today as it did in years past. Our history is the story of Texas’ unique culture of entrepreneurism, individualism, and multiculturalism.