Modeling and Characterization of an Electromagnetic System for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selecting the Optimal Inductor for Power Converter Applications

Selecting the Optimal Inductor for Power Converter Applications BACKGROUND SDR Series Power Inductors Today’s electronic devices have become increasingly power hungry and are operating at SMD Non-shielded higher switching frequencies, starving for speed and shrinking in size as never before. Inductors are a fundamental element in the voltage regulator topology, and virtually every circuit that regulates power in automobiles, industrial and consumer electronics, SRN Series Power Inductors and DC-DC converters requires an inductor. Conventional inductor technology has SMD Semi-shielded been falling behind in meeting the high performance demand of these advanced electronic devices. As a result, Bourns has developed several inductor models with rated DC current up to 60 A to meet the challenges of the market. SRP Series Power Inductors SMD High Current, Shielded Especially given the myriad of choices for inductors currently available, properly selecting an inductor for a power converter is not always a simple task for designers of next-generation applications. Beginning with the basic physics behind inductor SRR Series Power Inductors operations, a designer must determine the ideal inductor based on radiation, current SMD Shielded rating, core material, core loss, temperature, and saturation current. This white paper will outline these considerations and provide examples that illustrate the role SRU Series Power Inductors each of these factors plays in choosing the best inductor for a circuit. The paper also SMD Shielded will describe the options available for various applications with special emphasis on new cutting edge inductor product trends from Bourns that offer advantages in performance, size, and ease of design modification. -

Powder Material for Inductor Cores Evaluation of MPP, Sendust and High flux Core Characteristics Master of Science Thesis

Powder Material for Inductor Cores Evaluation of MPP, Sendust and High flux core characteristics Master of Science Thesis JOHAN KINDMARK FREDRIK ROSEN´ Department of Energy and Environment Division of Electric Power Engineering CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY G¨oteborg, Sweden 2013 Powder Material for Inductor Cores Evaluation of MPP, Sendust and High flux core characteristics JOHAN KINDMARK FREDRIK ROSEN´ Department of Energy and Environment Division of Electric Power Engineering CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY G¨oteborg, Sweden 2013 Powder Material for Inductor Cores Evaluation of MPP, Sendust and High flux core characteristics JOHAN KINDMARK FREDRIK ROSEN´ c JOHAN KINDMARK FREDRIK ROSEN,´ 2013. Department of Energy and Environment Division of Electric Power Engineering Chalmers University of Technology SE–412 96 G¨oteborg Sweden Telephone +46 (0)31–772 1000 Chalmers Bibliotek, Reproservice G¨oteborg, Sweden 2013 Powder Material for Inductor Cores Evaluation of MPP, Sendust and High flux core characteristics JOHAN KINDMARK FREDRIK ROSEN´ Department of Energy and Environment Division of Electric Power Engineering Chalmers University of Technology Abstract The aim of this thesis was to investigate the performanceof alternative powder materials and compare these with conventional iron and ferrite cores when used as inductors. Permeability measurements were per- formed where both DC-bias and frequency were swept, the inductors were put into a small buck converter where the overall efficiency was measured. The BH-curve characteristics and core loss of the materials were also investigated. The materials showed good performance compared to the iron and ferrite cores. High flux had the best DC-bias characteristics while Sendust had the best performance when it came to higher fre- quencies and MPP had the lowest core losses. -

Magnetics Design for Switching Power Supplies Lloydh

Magnetics Design for Switching Power Supplies LloydH. Dixon Section 1 Introduction Experienced SwitchMode Power Supply design- ers know that SMPS success or failure depends heav- ily on the proper design and implementation of the magnetic components. Parasitic elements inherent in high frequency transformers or inductors cause a va- riety of circuit problems including: high losses, high voltage spikes necessitating snubbers or clamps, poor cross regulation between multiple outputs, noise cou- pling to input or output, restricted duty cycle range, Figure 1-1 Transformer Equivalent Circuit etc. Figure I represents a simplified equivalent circuit of a two-output forward converter power transformer, optimized design, (3) Collaborate effectively with showing leakage inductances, core characteristics experts in magnetics design, and possibly (4) Become including mutual inductance, dc hysteresis and satu- a "magnetics expert" in his own right. ration, core eddy current loss resistance, and winding Obstacles to learning magnetics design distributed capacitance, all of which affect SMPS In addition to the lack of instruction in practical performance. magnetics mentioned above, there are several other With rare exception, schools of engineering pro- problems that make it difficult for the SMPS designer vide very little instruction in practical magnetics rele- to feel "at home" in the magnetics realm: vant to switching power supply applications. As a .Archaic concepts and practices. Our great- result, magnetic component design is usually dele- grandparents probably had a better understanding gated to a self-taught expert in this "black art". There of practical magnetics than we do today. Unfor- are many aspects in the design of practical, manu- tunately, in an era when computation was diffi- facturable, low cost magnetic devices that unques- cult, our ancestors developed concepts intended tionably benefit from years of experience in this field. -

Electromagnets and Their Applications

International Journal of Industrial Electronics and Electrical Engineering, ISSN(p): 2347-6982, ISSN(e): 2349-204X Volume-5, Issue-8, Aug.-2017, http://iraj.in ELECTROMAGNETS AND THEIR APPLICATIONS SHAHINKARIMAGHAIE Bachelor of Electrical Engineering, Yazd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Yazd, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Abstract- Electric current flowing through a wire wound around an iron nail creates a magnetic field, which caused an iron nail to become a temporary magnet. The nail can then be used to pick up paper clips. When the electric current is cut off, the nail loses its magnetic property and the paper clips fall off. The students will make an elecromagnet that will attract a paper clip. They will then increase the strength of an electromagnet(improve on their initial design) so that it will attract an increased number of paper clips. The participants will also compare the properties of magnets and electromagnets. However, unlike a permanent magnet that needs no power, an electromagnet requires a continuous supply of current to maintain the magnetic field. Electromagnets are widely used as components of other electrical devices, such as motors. Electromagnets are also employed in industry for picking up and moving heavy iron objects such as scrap iron and steel. We will investigate engineering and industrial applications of the case study. Keywords- Electromagnet, Application, Engineering. I. INTRODUCTION William Sturgeon. If you have ever played with a really powerful magnet, you have probably noticed Electromagnet, device in which magnetism is one problem. You have to be pretty strong to separate produced by an electric current. Any electric current the magnets again! Today, we have many uses for produces a magnetic field, but the field near an powerful magnets, but they wouldn’t be any good to ordinary straight conductor is rarely strong enough to us if we were not able to make them release the be of practical use. -

Effective Permeability of Multi Air Gap Ferrite Core 3-Phase

energies Article Effective Permeability of Multi Air Gap Ferrite Core 3-Phase Medium Frequency Transformer in Isolated DC-DC Converters Piotr Dworakowski 1,* , Andrzej Wilk 2 , Michal Michna 2 , Bruno Lefebvre 1, Fabien Sixdenier 3 and Michel Mermet-Guyennet 1 1 Power Electronics & Converters, SuperGrid Institute, 69100 Villeurbanne, France; [email protected] (B.L.); [email protected] (M.M.-G.) 2 Faculty of Electrical and Control Engineering, Gda´nskUniversity of Technology, 80-233 Gdansk, Poland; [email protected] (A.W.); [email protected] (M.M.) 3 Univ Lyon, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, INSA Lyon, ECLyon, CNRS, Ampère, 69100 Villeurbanne, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 4 February 2020; Accepted: 11 March 2020; Published: 14 March 2020 Abstract: The magnetizing inductance of the medium frequency transformer (MFT) impacts the performance of the isolated dc-dc power converters. The ferrite material is considered for high power transformers but it requires an assembly of type “I” cores resulting in a multi air gap structure of the magnetic core. The authors claim that the multiple air gaps are randomly distributed and that the average air gap length is unpredictable at the industrial design stage. As a consequence, the required effective magnetic permeability and the magnetizing inductance are difficult to achieve within reasonable error margins. This article presents the measurements of the equivalent B(H) and the equivalent magnetic permeability of two three-phase MFT prototypes. The measured equivalent B(H) is used in an FEM simulation and compared against a no load test of a 100 kW isolated dc-dc converter showing a good fit within a 10% error. -

Magnetics in Switched-Mode Power Supplies Agenda

Magnetics in Switched-Mode Power Supplies Agenda • Block Diagram of a Typical AC-DC Power Supply • Key Magnetic Elements in a Power Supply • Review of Magnetic Concepts • Magnetic Materials • Inductors and Transformers 2 Block Diagram of an AC-DC Power Supply Input AC Rectifier PFC Input Filter Power Trans- Output DC Outputs Stage former Circuits (to loads) 3 Functional Block Diagram Input Filter Rectifier PFC L + Bus G PFC Control + Bus N Return Power StageXfmr Output Circuits + 12 V, 3 A - + Bus + 5 V, 10 A - PWM Control + 3.3 V, 5 A + Bus Return - Mag Amp Reset 4 Transformer Xfmr CR2 L3a + C5 12 V, 3 A CR3 - CR4 L3b + Bus + C6 5 V, 10 A CR5 Q2 - + Bus Return • In forward converters, as in most topologies, the transformer simply transmits energy from primary to secondary, with no intent of energy storage. • Core area must support the flux, and window area must accommodate the current. => Area product. 4 3 ⎛ PO ⎞ 4 AP = Aw Ae = ⎜ ⎟ cm ⎝ K ⋅ΔB ⋅ f ⎠ 5 Output Circuits • Popular configuration for these CR2 L3a voltages---two secondaries, with + From 12 V 12 V, 3 A a lower voltage output derived secondary CR3 C5 - from the 5 V output using a mag CR4 L3b + amp postregulator. From 5 V 5 V, 10 A secondary CR5 C6 - CR6 L4 SR1 + 3.3 V, 5 A CR8 CR7 C7 - Mag Amp Reset • Feedback to primary PWM is usually from the 5 V output, leaving the +12 V output quasi-regulated. 6 Transformer (cont’d) • Note the polarity dots. Xfmr CR2 L3a – Outputs conduct while Q2 is on. -

Study on Characteristics of Electromagnetic Coil Used in MEMS Safety and Arming Device

micromachines Article Study on Characteristics of Electromagnetic Coil Used in MEMS Safety and Arming Device Yi Sun 1,2,*, Wenzhong Lou 1,2, Hengzhen Feng 1,2 and Yuecen Zhao 1,2 1 National Key Laboratory of Electro-Mechanics Engineering and Control, School of Mechatronical Engineering, Beijing Institute of technology, Beijing 100081, China; [email protected] (W.L.); [email protected] (H.F.); [email protected] (Y.Z.) 2 Beijing Institute of Technology, Chongqing Innovation Center, Chongqing 401120, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-158-3378-5736 Received: 27 June 2020; Accepted: 27 July 2020; Published: 31 July 2020 Abstract: Traditional silicon-based micro-electro-mechanical system (MEMS) safety and arming devices, such as electro-thermal and electrostatically driven MEMS safety and arming devices, experience problems of high insecurity and require high voltage drive. For the current electromagnetic drive mode, the electromagnetic drive device is too large to be integrated. In order to address this problem, we present a new micro electromagnetically driven MEMS safety and arming device, in which the electromagnetic coil is small in size, with a large electromagnetic force. We firstly designed and calculated the geometric structure of the electromagnetic coil, and analyzed the model using COMSOL multiphysics field simulation software. The resulting error between the theoretical calculation and the simulation of the mechanical and electrical properties of the electromagnetic coil was less than 2% under the same size. We then carried out a parametric simulation of the electromagnetic coil, and combined it with the actual processing capacity to obtain the optimized structure of the electromagnetic coil. -

Magnetic Materials: Hysteresis

Magnetic Materials: Hysteresis Ferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic materials have non-linear initial magnetisation curves (i.e. the dotted lines in figure 7), as the changing magnetisation with applied field is due to a change in the magnetic domain structure. These materials also show hysteresis and the magnetisation does not return to zero after the application of a magnetic field. Figure 7 shows a typical hysteresis loop; the two loops represent the same data, however, the blue loop is the polarisation (J = µoM = B-µoH) and the red loop is the induction, both plotted against the applied field. Figure 7: A typical hysteresis loop for a ferro- or ferri- magnetic material. Illustrated in the first quadrant of the loop is the initial magnetisation curve (dotted line), which shows the increase in polarisation (and induction) on the application of a field to an unmagnetised sample. In the first quadrant the polarisation and applied field are both positive, i.e. they are in the same direction. The polarisation increases initially by the growth of favourably oriented domains, which will be magnetised in the easy direction of the crystal. When the polarisation can increase no further by the growth of domains, the direction of magnetisation of the domains then rotates away from the easy axis to align with the field. When all of the domains have fully aligned with the applied field saturation is reached and the polarisation can increase no further. If the field is removed the polarisation returns along the solid red line to the y-axis (i.e. H=0), and the domains will return to their easy direction of magnetisation, resulting in a decrease in polarisation. -

MT Series High-Power Floor-Standing Programmable DC Power Supply • Expandable Into the Multi-Megawatts

MT Series High-Power Floor-Standing Programmable DC Power Supply • Expandable into the Multi-Megawatts Overview Magna-Power Electronics MT Series uses the same reliable current-fed power processing technology and controls as the rest of the MagnaDC programmable power supply product line, but with larger high-power modules: individual 100 kW, 150 kW and 250 kW power supplies. The high-frequency IGBT-based MT Series units are among the largest standard switched-mode power supplies on the market, minimizing the number of switching components when comparing to smaller module sizes. Scaling in the multi-megawatts is accomplished using the UID47 device, which provides master-slave control: one power supply takes command over the remaining units, for true system operation. As an added 100 kW and 150 kW Models 250 kW Models safety measure, all MT Series units include an input AC breaker rated for full power. 250 kW modules come standard with an embedded 12-pulse harmonic neutralizer, Models ensuring low total harmonic distortion (THD). 2 2 2 Even higher quality AC waveforms are available 100 kW 150 kW 250 kW 500 kW 750 kW 1000 kW with an external additional 500 kW 24-pulse 1 or 1000 kW 48-pulse harmonic neutralizers, Max Voltage Max Current Ripple Efficiency designed and manufactured exclusively by (Vdc) (Adc) (mVrms) Magna-Power for its MT Series products. 16 6000 N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 35 90 20 5000 N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 40 90 25 N/A 6000 N/A N/A N/A N/A 40 90 32 3000 4500 N/A N/A N/A N/A 40 90 40 2500 3750 6000 12000 18000 24000 40 91 50 2000 3000 5000 10000 15000 20000 50 91 MT Series Model Ordering Guide 60 1660 2500 4160 8320 12480 16640 60 91 80 1250 1850 3000 6000 9000 12000 60 91 There are 72 different models in the MT Series spanning power levels: 100 kW, 150 kW, 250 kW. -

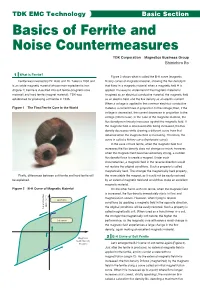

Basics of Ferrite and Noise Countermeasures TDK Corporation Magnetics Business Group Shinichiro Ito

TDK EMC Technology Basic Section Basics of Ferrite and Noise Countermeasures TDK Corporation Magnetics Business Group Shinichiro Ito What is Ferrite? 1 Figure 2 shows what is called the B-H curve (magnetic Ferrite was invented by Dr. Kato and Dr. Takei in 1930 and history curve) of magnetic material, showing the flux density B is an oxide magnetic material whose main ingredient is iron that flows in a magnetic material when a magnetic field H is (Figure 1) Ferrite is classified into soft ferrite (magnetic core applied. It is easy to understand if the magnetic material is material) and hard ferrite (magnet material). TDK was imagined as an electrical conductive material, the magnetic field established for producing soft ferrite in 1935. as an electric field, and the flux density as an electric current. When a voltage is applied to the common electrical conductive Figure 1 The First Ferrite Core in the World material, a current flows in proportion to the voltage; then, if the voltage is decreased, the current decreases in proportion to the voltage (Ohm’s Law). In the case of the magnetic material, the flux density non-linearly increases against the magnetic field. If the magnetic field is decreased after being increased, the flux density decreases while drawing a different curve from that obtained when the magnetic field is increasing. Therefore, the curve is called a history curve (hysteresis curve). In the case of hard ferrite, when the magnetic field first increases the flux density does not change so much, however, when the magnetic field becomes extremely strong, a sudden flux density flows to create a magnet. -

Assignment 3

PHYSICS 2800 – 2nd TERM Introduction to Materials Science Assignment 3 Date of distribution: Tuesday, March 9, 2010 Date for solutions to be handed in: Tuesday, March 16, 2010 -7 2 You may assume the standard values µ0 = 4 π × 10 kg-m/C for the permeability of vacuum -24 2 and µB = 9.27 × 10 A-m for the Bohr magneton. 3 1. Nickel is a ferromagnetic metal with density 8.90 g/cm . Given that Avogadro’s number NA = 6.02 × 10 23 atoms/mol and the atomic weight of Ni is 58.7, calculate the number of atoms of Ni per cubic metre. If one atom of Ni has a magnetic moment of 0.6 Bohr magnetons, deduce the saturation magnetization Ms and the saturation magnetic induction Bs for Ni. Answer: 3 The saturation magnetization is given by Ms = 0.6 µBN , where N is the number of atoms/m . ρN A But N = , where ρ is the density and ANi is the atomic weight of Ni. ANi 90.8( ×10 6 g/m 3 )( 02.6 ×10 23 atoms/mol ) So N = = 9.13 × 10 28 atoms/m 3. 58 7. g/mol -24 28 5 Then Ms = 0.6 (9.27 × 10 )( 9.13 × 10 ) = 5.1 × 10 A/m. Finally (from the lecture notes), -7 5 BS = µ0MS = (4 π × 10 )(5.1 × 10 ) = 0.64 Tesla. 2. The magnetization within a bar of some metal alloy is 1.2 × 10 6 A/m when the H field is 200 A/m. Calculate (a) the magnetic susceptibility χm of this alloy, (b) the permeability µ, and (c) the magnetic induction B within the alloy. -

Basic Design and Engineering of Normal-Conducting, Iron-Dominated Electromagnets

Basic design and engineering of normal-conducting, iron-dominated electromagnets Th. Zickler CERN, Geneva, Switzerland Abstract The intention of this course is to provide guidance and tools necessary to carry out an analytical design of a simple accelerator magnet. Basic concepts and magnet types will be explained as well as important aspects which should be considered before starting the actual design phase. The central part of this course is dedicated to describing how to develop a basic magnet design. Subjects like the layout of the magnetic circuit, the excitation coils, and the cooling circuits will be discussed. A short introduction to materials for the yoke and coil construction and a brief summary about cost estimates for magnets will complete this topic. 1 Introduction The scope of these lectures is to give an overview of electromagnetic technology as used in and around particle accelerators considering normal-conducting, iron-dominated electromagnets generally restricted to direct current situations where we assume that the voltages generated by the change of flux and possible resulting eddy currents are negligible. Permanent and superconducting magnet technologies as well as special magnets like kickers and septa are not covered in this paper; they were part of dedicated special lectures. It is clear that it is difficult to give a complete and exhaustive summary of magnet design since there are many different magnet types and designs; in principle the design of a magnet is limited only by the laws of physics and the imagination of the magnet designer. Furthermore, each laboratory and each magnet designer or engineer has his own style of approaching a particular magnet design.