Rudolf Steiner and Peter Sellars: Theory to Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Season of Thrilling Intrigue and Grand Spectacle –

A Season of Thrilling Intrigue and Grand Spectacle – Angel Blue as MimÌ in La bohème Fidelio Rigoletto Love fuels a revolution in Beethoven’s The revenger becomes the revenged in Verdi’s monumental masterpiece. captivating drama. Greetings and welcome to our 2020–2021 season, which we are so excited to present. We always begin our planning process with our dreams, which you might say is a uniquely American Nixon in China Così fan tutte way of thinking. This season, our dreams have come true in Step behind “the week that changed the world” in Fidelity is frivolous—or is it?—in Mozart’s what we’re able to offer: John Adams’s opera ripped from the headlines. rom-com. Fidelio, to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. Nixon in China by John Adams—the first time WNO is producing an opera by one of America’s foremost composers. A return to Russian music with Musorgsky’s epic, sweeping, spectacular Boris Godunov. Mozart’s gorgeous, complex, and Boris Godunov La bohème spiky view of love with Così fan tutte. Verdi’s masterpiece of The tapestry of Russia's history unfurls in Puccini’s tribute to young love soars with joy a family drama and revenge gone wrong in Rigoletto. And an Musorgsky’s tale of a tsar plagued by guilt. and heartbreak. audience favorite in our lavish production of La bohème, with two tremendous casts. Alongside all of this will continue our American Opera Initiative 20-minute operas in its 9th year. Our lineup of artists includes major stars, some of whom SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS we’re thrilled to bring to Washington for the first time, as well as emerging talents. -

Oceanic Migrations

San Francisco Contemporary Music Players on STAGE series Oceanic Migrations MICHAEL GORDON ROOMFUL OF TEETH SPLINTER REEDS September 14, 2019 Cowell Theater Fort Mason Cultural Center San Francisco, CA SFCMP SAN FRANCISCO CONTEMPORARY MUSIC PLAYERS San Francisco Contemporary Music Brown, Olly Wilson, Michael Gordon, Players is the West Coast’s most Du Yun, Myra Melford, and Julia Wolfe. long-standing and largest new music The Contemporary Players have ensemble, comprised of twenty-two been presented by leading cultural highly skilled musicians. For 49 years, festivals and concert series including the San Francisco Contemporary Music San Francisco Performances, Los Players have created innovative and Angeles Monday Evening Concerts, Cal artistically excellent music and are one Performances, the Stern Grove Festival, Tod Brody, flute Kate Campbell, piano of the most active ensembles in the the Festival of New American Music at Kyle Bruckmann, oboe David Tanenbaum, guitar United States dedicated to contemporary CSU Sacramento, the Ojai Festival, and Sarah Rathke, oboe Hrabba Atladottir, violin music. Holding an important role in the France’s prestigious MANCA Festival. regional and national cultural landscape, The Contemporary Music Players Jeff Anderle, clarinet Susan Freier, violin the Contemporary Music Players are a nourish the creation and dissemination Peter Josheff, clarinet Roy Malan, violin 2018 awardee of the esteemed Fromm of new works through world-class Foundation Ensemble Prize, and a performances, commissions, and Adam Luftman, -

Mahler's Song of the Earth

SEASON 2020-2021 Mahler’s Song of the Earth May 27, 2021 Jessica GriffinJessica SEASON 2020-2021 The Philadelphia Orchestra Thursday, May 27, at 8:00 On the Digital Stage Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Michelle DeYoung Mezzo-soprano Russell Thomas Tenor Mahler/arr. Schoenberg and Riehn Das Lied von der Erde I. Das Trinklied von Jammer der Erde II. Der Einsame im Herbst III. Von der Jugend IV. Von der Schönheit V. Der Trunkene im Frühling VI. Der Abschied First Philadelphia Orchestra performance of this version This program runs approximately 1 hour and will be performed without an intermission. This concert is part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. Our World Lead support for the Digital Stage is provided by: Claudia and Richard Balderston Elaine W. Camarda and A. Morris Williams, Jr. The CHG Charitable Trust Innisfree Foundation Gretchen and M. Roy Jackson Neal W. Krouse John H. McFadden and Lisa D. Kabnick The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Leslie A. Miller and Richard B. Worley Ralph W. Muller and Beth B. Johnston Neubauer Family Foundation William Penn Foundation Peter and Mari Shaw Dr. and Mrs. Joseph B. Townsend Waterman Trust Constance and Sankey Williams Wyncote Foundation SEASON 2020-2021 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yannick Nézet-Séguin Music Director Walter and Leonore Annenberg Chair Nathalie Stutzmann Principal Guest Conductor Designate Gabriela Lena Frank Composer-in-Residence Erina Yashima Assistant Conductor Lina Gonzalez-Granados Conducting Fellow Frederick R. -

Don Giovanni's Case

RLCS, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72 – Pages 1.238 to 1.260 [Research] [Funded] | DOI:10.4185/RLCS-2017-1217en| ISSN 1138-5820 | Year 2017 How to cite this article in bibliographies / References I Villanueva-Benito, I Lacasa-Mas (2017): “The use of audiovisual language in the expansion of performing arts outside theater: Don Giovanni’s case, by Mozart”. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72, pp. 1.238 to 1.260. http://www.revistalatinacs.org/072paper/1217/67en.html DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-2017-1217en The use of audiovisual language in the expansion of performing arts outside theater: Don Giovanni’s case, by Mozart Isabel Villanueva-Benito [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Associate professor. Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (Spain). Visiting Researcher. University of Los Angeles, California (United States). [email protected] Iván Lacasa-Mas [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Full Professor. Universitat Internacional de Catalunya. Visiting Scholar, University of Texas at Austin, Texas (United States). [email protected] Abstract Introduction: This paper studies opera films of centuries XX and XXI, in order to identify whether the language used is closer to the theater standards of the performing arts typical of live or those of audiovisual media. Methodology: We have performed an exhaustive contents analysis of the end of the first act from 29 filmed versions of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, according to three categories: type of film, type of camera shots used and type of editing. From these, we evaluated 41 variables. Results: We conclude that, with the purpose to expand a performance such as the operatic outside theaters, even in the XXI century, live still limits the form of films. -

Peter Sellars Et Le Théâtre Du Présent Alexandre Lazaridès

Document généré le 23 sept. 2021 12:56 Jeu Revue de théâtre Peter Sellars et le théâtre du présent Alexandre Lazaridès Poésie-spectacle Numéro 112 (3), 2004 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/25345ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Cahiers de théâtre Jeu inc. ISSN 0382-0335 (imprimé) 1923-2578 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Lazaridès, A. (2004). Peter Sellars et le théâtre du présent. Jeu, (112), 142–146. Tous droits réservés © Cahiers de théâtre Jeu inc., 2004 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ ALEXANDRE LAZARIDÈS !l Peter Sellars et le théâtre du présent é à Pittsburgh en 1957, l'enfant terrible du théâtre américain, celui par qui le N scandale arrive et qui n'a cure des salles qui se vident, n'est pas près de rentrer dans le rang, en dépit de la quarantaine avancée. Bien au contraire, ce qui était in tuition quelque peu brouillonne à l'origine est devenu parti pris étayé par une longue expérience et soutenu par une force de conviction inébranlable. Boutades, paradoxes et contradictions se concilient chez lui avec un raisonnement multiple qui peut s'exprimer autant par des conférences et des essais que par l'action pédagogique auprès du public. -

BEKANNTMACHUNG Die Preisträger Des Polar Music Prize

BEKANNTMACHUNG Die Preisträger des Polar Music Prize 2014 sind: CHUCK BERRY UND PETER SELLARS Die Begründung für Chuck Berry Der Polarpreis 2014 wird Chuck Berry von St. Louis, USA, verliehen. An jenem Tag im Mai 1955, als Chuck Berry seine Debutsingel "Maybellene" einspielte, wurden die Parameter der Rockmusik definiert. Chuck Berry war der Pionier des Rock'n'Roll, der der E-Gitarre als Hauptinstrument der Rockmusik den Weg bereitete. Alle Riffs und Soli, die Rockgitarristen in den letzten 60 Jahren gespielt haben, enthalten DNA- Spuren, die sich auf Chuck Berry zurückführen lassen. The Rolling Stones, The Beatles und eine Million andere Bands haben ihr Handwerk erlernt, indem sie Stücke von Chuck Berry eingeübten. Daneben ist Chuck Berry ein meisterhafter Songwriter. In drei Minuten kann er Bilder aus dem Alltag eines Jugendlichen und dessen Träume skizzieren, nicht selten mit einem Auto im Zentrum. Chuck Berry, geboren 1926, war der erste, der auf den Highway hinausgefahren ist um zu verkünden: Wir alle sind "born to run". Preisbegründung für Peter Sellars: Der Polarpreis 2014 geht an Peter Sellars aus Pittsburgh, USA. Der Regisseur Peter Sellars ist das beste lebende Beispiel dafür, um was es beim Polarpreis geht: Musik sichtbar zu machen und sie in einem neuen Kontext zu präsentieren. Mit seinen kontroversen Inszenierungen von Opern und Theaterstücken hat Peter Sellars alles, von Krieg und Hunger bis hin zu Religion und Globalisierung, auf die Bühne gebracht. Sellars hat Mozart in den Luxus des Trump Tower und in den Drogenhandel von Spanish Harlem versetzt, eine Oper über Nixons Besuch in China inszeniert und Kafkas Sauberkeitswahn vertont. -

Festival Milestones

MILESTONES 1947 May 4 - First concert features French baritone Martial Singher with Paul Ulanowsky in a recital covering repertoire from Rameau to Ravel at Ojai’s Nordhoff Auditorium. 1948 Lawrence Morton becomes first program annotator and begins his association with the Festival; Igor Stravinky’s Histoire du soldat (A Solider’s Tale) is billed as the premiere of the final version of his work. 1949 Ojai Festivals, Ltd. is officially launched as a non-profit organization. 1952 The Festival holds first outdoor concert at the Libbey Bowl. 1953 Lukas Foss makes his first Ojai appearance as conductor. 1954 Lawrence Morton becomes first Artistic Director. 1955 Igor Stravinsky conducts his own works at the Festival. 1956 Stravinsky conducts his own Les Noces for Ojai audiences; permanent benches are added to the Libbey Bowl doubling the seating capacity to 750. 1957 Aaron Copland makes Ojai debut. 1960 For the first time, all Festival concerts are held at the Libbey Bowl. 1962 Jazz flutist Eric Dolphy performs Density 21.5 for solo flute by Edgard Varèse; the Festival includes a four-day prelude of discussions lectures/concerts with Luciano Berio, Milton Babbitt, Gunther Schuller and Lukas Foss. 1963 Foss experiments with music from Don Giovanni using three orchestras to create a kind of stereophonic surround sound at the Bowl; Mauricio Kagel is guest composer/conductor. 1964 Ingolf Dahl (USC faculty composer) is Music Director and Ojai becomes a northern “outpost” for the USC’s music department. 1965 19-year-old pianist Michael Tilson Thomas is featured in concert; Harold Shapero’s Serenade in D for String Orchestra and Ramiro Cortes’ Concerto for Violin and Strings are premiered. -

Only the Sound Remains (U.S

Saturday, November 17, 2018 at 7:30 pm Sunday, November 18, 2018 at 5:00 pm Pre-performance discussion with Kaija Saariaho, Peter Sellars, and Ara Guzelimian on Sunday, November 18 at 3:45 pm in the Agnes Varis and Karl Leichtman Studio Only the Sound Remains (U.S. premiere) An opera by Kaija Saariaho Directed by Peter Sellars This performance is approximately two hours and 20 minutes long, including a 20-minute intermission. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Rose Theater Please make certain all your electronic devices Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall are switched off. WhiteLightFestival.org The White Light Festival 2018 is made possible by Join the conversation: #WhiteLightFestival The Shubert Foundation, The Katzenberger Foundation, Inc., Laura Pels International Foundation for Theater, The Joelson Foundation, The Harkness Foundation for Dance, Great Performers Circle, Chairman’s Council, and Friends of Lincoln Center Public support is provided by New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature Nespresso is the Official Coffee of Lincoln Center NewYork-Presbyterian is the Official Hospital of Lincoln Center A co-production of Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam, Finnish National Opera, Opera National de Paris, Teatro Real, and Canadian Opera Company. As one of the original co-commissioners of Kaija Saariaho’s Only the Sound Remains , the Canadian Opera Company is proud to support the North American premiere of this work at Lincoln Center’s White Light Festival In collaboration with GRAME, Lyon By arrangement with G. -

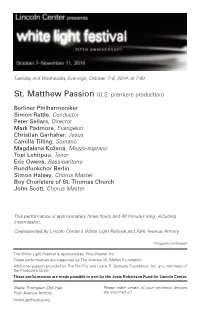

St. Matthew Passion (U.S

10-07 WL St Matthew_GP 9/24/14 12:00 PM Page 1 Tuesday and Wednesday Evenings, October 7–8, 2014, at 7:00 St. Matthew Passion (U.S. premiere production) Berliner Philharmoniker Simon Rattle , Conductor Peter Sellars , Director Mark Padmore , Evangelist Christian Gerhaher , Jesus Camilla Tilling , Soprano Magdalena Kožená , Mezzo-soprano Topi Lehtipuu , Tenor Eric Owens , Bass-baritone Rundfunkchor Berlin Simon Halsey , Chorus Master Boy Choristers of St. Thomas Church John Scott , Chorus Master This performance is approximately three hours and 40 minutes long, including intermission. Co-presented by Lincoln Center’s White Light Festival and Park Avenue Armory (Program continued) The White Light Festival is sponsored by Time Warner Inc. These performances are supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Additional support provided by The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. and members of the Producers Circle. These performances are made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Wade Thompson Drill Hall, Please make certain all your electronic devices Park Avenue Armory are switched off. WhiteLightFestival.org 10-07 WL St Matthew_GP 9/24/14 12:00 PM Page 2 Endowment support is provided by the American Upcoming White Light Festival Events: Express Cultural Preservation Fund. Thursday–Saturday Evenings, October 9–11, MetLife is the National Sponsor of Lincoln Center. at 8:00 in Baryshnikov Arts Center, Jerome Robbins Theater Movado is an Official Sponsor of Lincoln Center. Chalk and Soot (New York premiere) Dance Heginbotham United Airlines is the Official Airline of Lincoln Brooklyn Rider Center. Co-presented with Baryshnikov Arts Center WABC-TV is the Official Broadcast Partner of Friday Evening, October 10, at 7:30 Lincoln Center. -

On STAGE Series Carter and Beyond: Invention and Inspiration

San Francisco Contemporary Music Players on STAGE Series Carter and Beyond: Invention and Inspiration CARTER CHODOS SCHROEDER OCT 20, 2018 Taube Atrium Theater San Francisco, CA This event is San Francisco Contemporary Music Players Adam Luftman, trumpet Chris Froh, percussion David Tanenbaum, guitar Hannah Addario-Berry, cello Hrabba Atladottir, violin Jeff Anderle, clarinet Karen Gottlieb, harp Kate Campbell, piano Kyle Bruckmann, oboe The San Francisco Contemporary Music Players (SFCMP), a 24-member ensemble Loren Mach, percussion of highly skilled musicians, performs innovative contemporary classical music Meena Bhasin, viola based out of the San Francisco Bay Area. Nanci Severance, viola Nick Woodbury, percussion SFCMP aims to nourish the creation and dissemination of new works through Peter Josheff, clarinet high-quality musical performances, commissions, education and community Peter Wahrhaftig, tuba outreach. SFCMP promotes the music of composers from across cultures Richard Worn, contrabass and stylistic traditions who are creating a vast and vital 21st-century musical language. SFCMP seeks to share these experiences with as many people as Roy Malan, violin possible, both in and outside of traditional concert settings. Sarah Rathke, oboe Stephen Harrison, cello SFCMP evolved out of Bring Your Own Pillow concerts started in 1971 by Susan Freier, violin Charles Boone. Three years later, it was incorporated by Jean-Louis LeRoux and Tod Brody, flute Marcella DeCray who became its directors. Across its history, SFCMP has been led William -

Doctor Atomic a Guide for Educators

JOHN ADAMS Doctor Atomic A Guide for Educators ken howard / met opera Doctor Atomic THE WORK An opera in two acts, sung in English Stories of creation and destruction have long enjoyed a central place Music by John Adams in the human imagination. Yet for much of our history, the power to create and destroy was the stuff of legend—until, in 1945, scientific Libretto by Peter Sellars, adapted from original sources ingenuity put these powers very much in the hands of humankind. In the early morning hours of June 16, 1945, the United States tested an First performed on October 1, 2005, at San Francisco Opera atomic bomb in the remote New Mexico desert. The culmination of a massive, yearslong undertaking that involved more than 100,000 people across the United States, the test is often viewed as a triumph of science PRODUCTION and modern thought; for composer John Adams, it was a moment when Penny Woolcock the modern and the mythic came together with terrifying force. “The Production manipulation of the atom, the unleashing of that formerly inaccessible Julian Crouch Set Designer source of densely concentrated energy, was the great mythological tale Catherine Zuber of our time,” he observes. And in 2005, as the world celebrated the 60th Costume Designer anniversary of the end of World War II, Adams’s Doctor Atomic brought Brian MacDevitt this modern myth to the opera stage. Lighting Designer Andrew Dawson At the center of the story stands J. Robert Oppenheimer, the titular Choreographer doctor and a character as complex and conflicted as any mythological Leo Warner & Mark Grimmer hero. -

Chevalier, Nicole

NICOLE CHEVALIER dramatic coloratura soprano American born soprano Nicole Chevalier made her international breakthrough at the Salzburg Festival in the summer of 2019 as Elettra in Mozart’s Idomeneo with Teodor Currentzis and Peter Sellars. Since she sang the title role of La Traviata at Musikfest Bremen; Olympia, Antonia, Giulietta and Stella (Les Contes d’Hoffmann) at La Monnaie Brussels, Vitellia (La clemenza di Tito) as well as the title roles in Beethoven’s Leonore (Fidelio 1806) and Thaïs at Theater an der Wien, a concert version of Leonore with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, and a Corona proof production of Schönberg’s Pierrot Lunaire with Kent Nagano at Hamburgische Staatsoper (incl. a recording for the Biennale 2020). Upcoming plans feature her debut at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden as Vitellia (La clemenza di Tito) and Donna Elvira (Don Giovanni), followed in the 2021-22 sesaon by her Paris Opera debut as Iphigénie en Tauride in the Warlikowski production, role debut of Elisbeth in Don Carlo with Vincent Huguet, her de facto one-woman-show of La Traviata both in Basel, debut at Festspielhaus Baden-Baden with Thomas Hengelbrock as Elettrta in Idomeneo and debut at the Festival d’Aix 2023 edition with Tcherniakov as Despina in a new production of Così fan tutte. During her five years as a permanent ensemble member at the Komische Oper Berlin she worked extensively with Barrie Kosky with whom she created the 4-Female Leads in Les Contes d’Hoffmann, the title role in Handel’s Semele, the title role of Die Schöne Helena, Bernstein’s Cunegonde (Candide).