By Rail from Charlton Kings to the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Box Office Coordinator (Town Hall & Pittville Pump Room)

Box Office Coordinator (Town Hall & Pittville Pump Room) Salary: £23,632 - £26,211 per annum 40 hours per week Are you interested in great arts and culture? Come and work for us! We’re recruiting a Box Office Coordinator to lead our Sales and Customer Service team, and help us deliver an excellent customer experience, in a pivotal role that brings together our entertainment offer and the ticket-buying public. Based across The Cheltenham Town Hall and Pittville Pump Room, the role facilitates all our ticket income across our Co-Promotions and Hires activities across both venues. It involves oversight of accurate transactions, reporting and accounting, and vital feedback from our customers to continue to grow and develop our programme. You will be responsible for the smooth and efficient running of the box office on a day- to-day basis, meeting and greeting customers and answering queries, and delivering on our customer charter. You will use the ticketing system to oversee and facilitate sales, prepare customer and forecasting reports for the senior team and manage venue capacities and seating plans. You will coordinate our ticket commission income, the customer journey from ticket purchase to event attendance, and be a vital component of the Cheltenham Town Hall and Pittville Pump Room development. For more information and an informal chat about the role please speak to Rhys Hopkin, Events & Programme Producer on [email protected] or call 01242 387440. For the job description and person specification please use the links provided on the vacancies page. To apply for this vacancy please email your CV with supporting statement to: [email protected] using ‘Box Office Coordinator CT223 as your reference. -

Cheltenham Needs Analysis

Cheltenham Needs Analysis Produced by Data and Analysis Team Gloucestershire County Council July 2019 Contents Thriving Economy and Workforce ......................................................................................... 4 1. The economy of Cheltenham ...................................................................................... 4 1.1 Gross Value Added ................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Jobs and workplace based employment ................................................................. 6 2. Cheltenham’s business base and entrepreneurial growth ........................................... 8 2.1 Active enterprises ................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Business start-ups ................................................................................................ 10 2.3 Business deaths ................................................................................................... 11 2.4 Survival rates ........................................................................................................ 12 2.5 Business size and turnover ................................................................................... 14 2.6 Self employment ................................................................................................... 17 3. The workforce........................................................................................................... 19 3.1 Employment -

VCH Gloucestershire

I thank John Chandler again for the excellent production and also all the contributors, without whom the newsletter would not exist. We hope you find our eleventh newsletter interesting and Welcome from the Editor informative. If you have any comments or further ideas, please let me know: [email protected]. Welcome to our eleventh newsletter, keeping you in David Aldred touch with the work of the County History Trust. Editor You can read of the latest developments below, but the most significant development since our last newsletter is that the drafts for Cheltenham Report from the Trust 1738-1852 are now publicly available on the academy website (http://www.vchglosacademy.org/ In common with many other charities, the Trust has Cheltenham1738.html). There you can read about decided to update its governance structure in the the building of the town’s iconic Pittville pump light of changes in charity legislation since 2013. We room. wanted to secure the benefits of being what is termed My thanks go to Jan Broadway for contacting a ‘Charitable Incorporated Organisation’, rather than contributors and who, with Jonathan Comber, has an old-style ‘Unincorporated Association’. Those distributed the digital version of the newsletter. who have been down this road with other groups Pittville pump room (David Aldred) VCH Gloucestershire Newsletter 11 July 2019 England’s greatest local history community project is working in Gloucestershire to foster public knowledge, understanding and appreciation1 of the history and heritage of the county. from a bronze bust of Sir Charles, a long-serving Cheltenham MP). These grants, and the new regular supporters who signed up after the same will know that it’s not possible to simply upgrade an meeting, are of course very welcome, but we have existing charity. -

A Busy Summer Ahead Civic Day and Midsummer Fiesta

The Newsletter of Cheltenham Civic Society Issue 11 | June 2018 Your regular update on how we are working to keep CHELTENHAM a great place to thrive Stall at Midsummer Fiesta, Montpellier Gardens A plethora of signs and ‘orphan’ post Civic Day map A busy summer ahead Civic Day and Midsummer Fiesta Feedback at our AGM in March the protection of our own conservation organised a competition that involves highlighted how seriously our members areas, including on-street parking, people visiting the community groups take the ‘streetscape’ of our town, street paraphernalia, poor street represented there to find out more including signage, footpaths and street furniture and equipment on buildings. about the great work that they do. furniture. In view of this we have Street Pride is particularly concerned Hollywood Bowl, Leisure@Cheltenham, decided to mark Civic Day on 16 June about unnecessary bollards, signs, Paint Yourself Pottery and the by participating in the national Street posts and guard rails, of which there Gloucestershire Warwickshire Steam Pride campaign, led by Civic Voice. are plenty in Cheltenham! Our team will Railway have already donated prizes We will focus on the High Street within note all these issues and we will report and vouchers - and there may be more! the town’s Central Conservation Area, the offenders to the relevant authorities. The Civic Society will also have its own between Barratt’s Mill Lane and the The Civic Society is also participating stall and will encourage new members Honeybourne Bridge. Cheltenham’s in the Midsummer Fiesta in Montpellier to join. Do come along and support us Local Development Framework Gardens on 7 July . -

Cheltlf12 Brochure

SponSorS & SupporterS Title sponsor In association with Broadcast Partner Principal supporters Global Banking Partner Major supporters Radio Partner Festival Partners Official Wine Working in partnership Official Cider 2 The Times Cheltenham Literature Festival dIREctor Festival Assistant Jane Furze Hannah Evans Artistic dIREctor Festival INTERNS Sarah Smyth Lizzie Atkinson, Jen Liggins BOOK IT! dIREctor development dIREctor Jane Churchill Suzy Hillier Festival Managers development OFFIcER Charles Haynes, Nicola Tuxworth Claire Coleman Festival Co-ORdinator development OFFIcER Rose Stuart Alison West Welcome what words will you use to describe your festival experience? Whether it’s Jazz, Science, Music or Literature, a Cheltenham Festival experience can be intellectually challenging, educational, fun, surprising, frustrating, shocking, transformational, inspiring, comical, beautiful, odd, even life-changing. And this year’s The Times Cheltenham Literature Festival is no different. As you will see when you browse this brochure, the Festival promises Contents 10 days of discussion, debate and interview, plus lots of new ways to experience and engage with words and ideas. It’s a true celebration of 2012 NEWS 3 - 9 the power of the word - with old friends, new writers, commentators, What’s happening at this year’s Festival celebrities, sports people and scientists, and from children’s authors, illustrators, comedians and politicians to leading opinion-formers. FESTIVAL PROGRAMME 10 - 89 Your day by day guide to events I can’t praise the team enough for their exceptional dedication and flair in BOOK IT! 91 - 101 curating this year’s inspiring programme. However, there would be no Festival Our Festival for families and without the wonderful enthusiasm of our partners and loyal audiences and we young readers are extremely grateful for all the support we receive. -

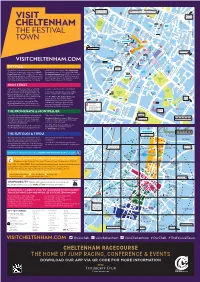

Cheltenham Racecourse (Map Ref E1) the Everyman Theatre (Map Ref D4) D H M B E Lk R S a Park Priory Th D Ed

n Tesco t e A4019 to Tewkesbury, t e e Y d r n l R e Pittville Pump Room, Leisure at Cheltenham, W d M5 North Junction 10, a e U r a EL R d L t L b B I l R T S Racecourse, Park & Ride and A435 to Evesham N G M Gallagher Retail Park ’s D T S D l s O A E D R ’ A N R R ER u l RO P T a u O A S h k D E P a R n C Y t c t U t P r i B4632 to A t e w O S t o w L e e C M a G S s r la d A W N t r L Winchcombe n e e e A 4 r n R 0 E u S S c e t u q e H l 1 L r y u l n & Broadway 9 S n a S i e O S B e r PO W l e e v d IN l E l t D t D O a v t a A e N C V i O n A l E R a M e O r P R r A u en Y t t D n ce R Winston D o R S e o BU s ad T M H g e PITTVILLE Churchill I r n ES a G n t P H i o PR r S o CIRCUS k Memorial S K t T t s M r e T ’ E t e R l S Holst t E l S Gardens E u s a e ’ t E R t r a Birthplace n r t T e e e P T S g e e e S Trinity Museum d t t r c t r n t S S o t a Long Millbrook l D S o S e S The Church q t e P Stay r r N Roundabout e i G a e t t h u v Brewery A Se h t t t n lki H B S L rk S o s S e r a B tre r i e et o n Quarter d o T L lm n r r e n R on G o o n g N y t e i o R y v f a t d G All Saints t e n O i len b e x s S t f W a n al o H s e T P i e Y l S t O t w o tre Church a u D et a g M r e rk e r S re Citizens S o t y n St t P r a T r St w B s A Warwick t e e S a n C N y s R S D Advice n o S e h t a h G Place d s W a & A h e A m g P t e R a o a e r E e n y t o St James’ r J n c T l r O K e i s o ’S d t b n a o e R R R n n n o l d O n o e a W s Roundabout p e N A e p m a r n R P n D b e n l r r S R k Chester e a C r t d o A H l -

CTP Phase 4 Original Etros - Formal Representations with Personal Data Redacted

CTP Phase 4 Original ETROs - Formal Representations with personal data redacted Enquiry Reference Date Enquiry Detail Number 1 29/06/2018 St Pauls Road I wish to see evidence that the council has undertaken formal risk assessments with regard to the effects of displacement of traffic into surrounding streets on road and public safety. 2 29/06/2018 Hales Road Closing the Boots Corner scheme for general traffic is a very bad decision. Traffic will now spread to residential areas and the fumes from Diesel as well as Petrol will now invade residential areas to the detrimental health of all residents, especially children and older people!! The Cheltenham Borough Council has NOT listened to the residents of Cheltenham which is a disgrace and it is surprising that the County Council has agreed to execute this scheme! This will certainly have repercussions in the Ballot Box at future Elections !! Shame on both the County Council and Cheltenham Borough Council, especially Cheltenham Borough Council !!! 3 29/06/2018 Battledown Approach A terrible plan, with no thought for alternative routes. Going to create more pollution due to traffic and drive people out of town. The dying town centre will truly be dead. What a waste of money! Do any tax payers want this? 4 03/07/2018 Bishop's Cleeve Totally agree with scheme except being able to not drive through town because of existing restrictions- not sure routes are viable without causing chaos. You need to create a clear run and by stopping Clarence street you have pushed traffic to side streets. -

Notice of a Meeting of Planning Committee Thursday, 20 April 2017

Notice of a meeting of Planning Committee Thursday, 20 April 2017 6.00 pm Council Chamber - Municipal Offices Membership Councillors: Garth Barnes (Chair), Bernard Fisher (Vice-Chair), Paul Baker, Mike Collins, Colin Hay, Karl Hobley, Adam Lillywhite, Helena McCloskey, Chris Nelson, Tony Oliver, Louis Savage, Diggory Seacome, Klara Sudbury, Pat Thornton and Simon Wheeler The Council has a substitution process and any substitutions will be announced at the meeting Agenda 1. APOLOGIES 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTE REST 3. DECLARATIONS OF INDE PENDENT SITE VISITS 4. PUBLIC QUESTIONS 5. MINUTES OF LAST MEET ING (Pages 7 - 24) 6. PLANNING/LISTED BUIL DING/CONSERVA TION AREA CONSENT/ADVERTISEMENT APPLICATIONS, APPLICATIONS FOR LAWFUL DEVELOPMENT CERTIFICATE AND TREE RELATED APPLICATIONS – SEE MAIN SCHEDULE a) 16/00202/OUT Land off Kidnappers Lane (Pages 25 - 208) b) 16/01907/FUL Sandfor d Court, Humphris Place (Pages 209 - 234) c) 16/02105/FUL Cotswold Grange Hotel, Pittville (Pages 235 - 268) Circus Road d) 17/00129/FUL Castle Dream Stud, Mill Lane, (Pages 269 - 296) Charlton Kings e) 17/00 149/FUL 22 Dagmar Road (Pages 297 - 304) 1 f) 17/00165/FUL 259 Gloucester Road (Pages 305 - 330) g) 17/00218/FUL 1 Hartley Close (Pages 331 - 338) h) 17/00268/LBC Municipal Offices (Pages 339 - 342) i) 17/00291/LBC Cheltenham Town Hall (Pages 343 - 346) j) 17/00395/FUL 24 Leyson Road, The Reddings (Pages 347 - 354) 7. ANY OTHER ITEMS THE CHAIRMAN DETERMINES URGENT AND REQUIRES A DECISION Contact Officer : Judith Baker, Planning Committee Co-ordinator, Email : [email protected] 2 3 5 Agenda Item 5 Page 7 Planning Committee 23 rd March 2017 Present: Members (14) Councillors Barnes, Chair (GB); Fisher, Vice-Chair (BF); Baker (PB); Collins (MC); Colin Hay (CH); Lillywhite (AL); McCloskey (HM); Nelson (CN); Oliver (TO); Savage (LS); Seacome (DS); Sudbury (KS); Thornton (PT); Wheeler (SW). -

Towards a Commissioning Strategy for Leisure and Culture Outcomes

Appendix A Towards a Commissioning Strategy For Leisure and Culture Outcomes Preliminary Analysis – July 2011 Table of contents 1 Introduction and Context ............................................................................................... 3 2 Background to Leisure and Culture services ............................................................... 11 3 Current Service Provision ............................................................................................ 14 4 Cheltenham’s Leisure and Culture Offer ...................................................................... 24 5 Alternative Delivery Arrangements .............................................................................. 28 6 From Needs Assessment to Defining Outcomes – The Current Model Exercise ........ 31 7 Current Model Exercise Assessment and Recommendations ..................................... 36 8 Plan for next stage and capacity management ............................................................ 46 9. Consultation ................................................................................................................ 46 Page 2 of 47 Towards a Commissioning Strategy For Leisure and Culture Appendix A July 2011 1 Introduction and Context 1.1 Cheltenham’s journey towards becoming a strategic commissioning authority began with the publication of Sir Michael Lyons report (2007) Place-shaping: a shared ambition for the future of local government. Sir Michael said “I believe that local government is an essential part of our system of -

2020Venue Guide

2020 VENUE GUIDE meetincheltenham.co.uk EVENT PLANNING MEET IN CHELTENHAM 2020 Meet in Cheltenham can help you with a range of services when planning your Cheltenham is a large Regency spa town located on the edge of the Cotswolds and event. Whether you are looking to organise a large conference over a number in the county of Gloucestershire, giving you easy access to Wales, the Midlands and of days, a one-off bespoke event or a small meeting we’re here to help. London. We’re just an hour away from hubs like Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff and Oxford, and London is just over two hours’ away by train. Working with over 20 hotels, unique venues and event suppliers in Cheltenham and the surrounding area we provide a free to use venue finding service and specialise With direct access to major motorways, including the M4 and M5, plus mainline in providing competitive venue options and practical destination support. railway stations and international airports, Cheltenham is easily accessible whether you’re travelling by road, rail or air. We can also negotiate bedroom rates at residential properties for bookings of 20 or more people. We can reserve the required accommodation and provide an As the home of GCHQ, Cheltenham is at the centre of the UK’s Cyber Tech industry. easy to use link in order to manage delegate room bookings online. Cheltenham is also known as ‘The Festival Town’, testament to its vibrant cultural offer and year-round calendar of major festivals and events. In addition to venue and accommodation finding we also provide the following -

Service Number 42/43

4 | Transport Network Analysis SERVICE NUMBER 42/43 42 3 0 3 6 9 12 km Connecting Cheltenham - Baseline Report 107 4 | Transport Network Analysis SERVICE NUMBER 51 51 3 0 3 6 9 12 km 108 Connecting Cheltenham - Baseline Report 4 | Transport Network Analysis SERVICE NUMBER 93 93 3 0 3 6 9 12 km Connecting Cheltenham - Baseline Report 109 4 | Transport Network Analysis SERVICE NUMBER 94 94 3 0 3 6 9 12 km 110 Connecting Cheltenham - Baseline Report 4 | Transport Network Analysis SERVICE NUMBER 94U 94U 3 0 3 6 9 12 km Connecting Cheltenham - Baseline Report 111 4 | Transport Network Analysis SERVICE NUMBER 97 97 3 0 3 6 9 12 km 112 Connecting Cheltenham - Baseline Report 4 | Transport Network Analysis SERVICE NUMBER 99 99 3 0 3 6 9 12 km Connecting Cheltenham - Baseline Report 113 114 Connecting Cheltenham - Baseline Report 5 | Disruptive Technologies Connecting Cheltenham - Baseline Report 115 5 | Disruptive Technologies DISRUPTIVE TECHNOLOGIES Transport is undergoing disruption. A variety of technological create more mobility and more car use at the expense of public of far fewer vehicles on the road in some future visions, in the advances are combining to offer both new forms of transportation transport, walking and cycling. In so doing, the commercial shorter term at least, the numbers of vehicles on the road may as well as radically changing the way services are delivered viability of public transport could be further eroded, exacerbating increase. and accessed. These include apps providing dynamic journey accessibility and inclusion for groups who can’t afford (or don’t planning and routeing information so that travellers can plan want to) engage with these new services, and we could end up The strategy should, therefore, try to prioritise shared transit, their journeys ‘on the go’ in response to real time network with more mobility, more congestion and more exclusion. -

Borough of Cheltenham at a Statutory Quarterly Meeting of the Town

Borough of Cheltenham At a Statutory Quarterly Meeting of the Town Council of the Borough or Cheltenham, duly convened and held at the Municipal Offices, in the said Borough, on Monday, 10th November, 1924, at 12 noon. Present: The Deputy Mayor (Alderman Charles Henry Margrett, C.B.E.) in the chair. Aldermen Clara Frances Winterbotham, Bendall, Green, Steel and Taylor Councillors Bastin, Major Cavenagh-Mainwaring, Dunn, O.B.E., Farrar, Leigh James, Mann, Moore, Pates, Pruen, Sawyer, St. Clair, Stewart, Thomas, Capt. Trye, C.B.E. and Yarnold. Apologies—Apologies for absence were received from Councillors Welstead and Whitaker. 1—Election of Councillors—The Town Clerk reported the election on the 1st inst. of the following as Councillors :— Frank Harry Bastin for the North Ward : George Owen William Dunn, O.B.E. for the Central Ward : John Poytress Pates for the East Ward : Arthur Sidney Fitzgerald Pruen for the South Ward : John Henry Trye (Capt.) C.B.E. for the Middle Ward : and Thomas Edwin Whitaker for the West Ward : and laid. before the Council their Declarations of Acceptance of Office. 5 2—Election of Mayor—It was unanimously Resolved, That Councillor Walter James Manser Dicks be and he is hereby re-elected Mayor of the Borough of Cheltenham for the ensuing year. The Mayor then made the Declaration of Acceptance of Office and took the Oath of Allegiance and Judicial Oath. The Mayor thereupon took the Chair. 3—Appointment of Deputy Mayor—The Mayor signified in writing that he had appointed Alderman Charles Henry Margrett, C.B.E., J.P., C.A., to be his Deputy, and it was Resolved, That such appointment be recorded upon the Minutes of the Council.