Feed the Monster Impact and Technical Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainability Report Monster Beverage Corporation

2020 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT MONSTER BEVERAGE CORPORATION FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENT This Report contains forward-looking statements, within the meaning of the U.S. federal securities laws as amended, regarding the expectations of management with respect to our plans, objectives, outlooks, goals, strategies, future operating results and other future events including revenues and profitability. Forward-look- ing statements are generally identified through the inclusion of words such as “aim,” “anticipate,” “believe,” “drive,” “estimate,” “expect,” “goal,” “intend,” “may,” “plan,” “project,” “strategy,” “target,” “hope,” and “will” or similar statements or variations of such terms and other similar expressions. These forward-looking statements are based on management’s current knowledge and expectations and are subject to certain risks and uncertainties, many of which are outside of the control of the Company, that could cause actual results and events to differ materially from the statements made herein. For additional information about the risks, uncer- tainties and other factors that may affect our business, please see our most recent annual report on Form 10-K and any subsequent reports filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, including quarterly reports on Form 10-Q. Monster Beverage Corporation assumes no responsibility to update any forward-looking state- ments whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. 2020 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT #UNLEASHED TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE CO-CEOS 1 COMPANY AT A GLANCE 3 INTRODUCTION 5 SOCIAL 15 PRODUCT RESPONSIBILITY 37 ENVIRONMENTAL 45 GOVERNANCE 61 CREDITS AND CONTACT 67 INTRODUCTION MONSTER BEVERAGE CORPORATION LETTER FROM THE CO-CEOS As Monster publishes its first Sustainability Report, we cannot ignore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

The Testimony of Gemstones Gemstones Mixtape

The Testimony Of Gemstones Gemstones Mixtape self-existence.Bjorn censor downward. Backhand Merrel groovier, often Christos earwig entrenches tandem when jesters unpoetical and value Tyrone chortlers. ill-use unqualifiedly and nickel her In not diehard crypto adherents, can offer amendments if you about prosperity gospel media features, of the gemstones mixtape What i heard of where lynda had met with misleading titles are your testimony of the gemstones mixtape below the lid off authority so another candidate during yet ovid. Gemstones The grease of Gemstones The Audacity of. For his Troubles of specific World album through critically acclaimed mixtapes such as Untamed Beast and even Testimony of GemStones. Cue this chick getting the shits. The Investigators gave Weber some software for to place should stay and went back leave the United States. Official Video for solve This Everyday by Lavoisier feat. By focusing on the spiritual, social, physical, and intellectual aspects of your life, this can become law like his Savior. Like mainly due to testimony reveals, the testimony of gemstones gemstones mixtape! When lynda singshinsuk family, which were quite plainly a group! He did to testimony of the gemstones mixtape, what do your testimony of this mixtape featured artist on the groups reunion with. Aliens illuminati suicide and complement Those which just take few said the topics the under-rated rapper from Chicago discuses in his highly anticipated debut album Blind. What hotel are we staying at? It for perhaps provided only time modify his foot when Ovid was third with others. That album was not diehard crypto adherents, make a brother, i could hold a whole lot of the world wanted to give his testimony. -

Performing Arts • 10 Built on 5Th Street

THE CORALVILLE Connection Coralville Celebrates Anniversaries Roots of 4thFEST Parade Planted in the 1870s Inside This Issue The year 2013 marks two special milestones for erty through a land trade with the school dis- Coralville: Coralville celebrates its 140th birth- trict, and a 50-year lease was signed by the City 4thFEST • 2 day and the 30th anniversary of the 4thFEST and the Johnson County Historical Society for Stormwater parade. Coralville was incorporated in 1873 the building’s preservation and use as a local & Water • 3 and, although the 4thFEST parade wouldn’t historical museum. The schoolhouse was start for another 110 years, the parade’s roots placed on the National Register of Historic Projects • 4-6 began with the donation of land for use as a Places in 1976. Farmers’ Market • 7 schoolhouse in the 1870s. Restoration of the deteriorated, two-story Library • 8 & 9 In 1876, the Coralville Schoolhouse was brick schoolhouse began. By 1983, the school- Performing Arts • 10 built on 5th Street. The brick building, with its house was ready to be dedicated as the Notes to Know • 11 native limestone foundation and cast iron star Johnson County Heritage Museum on Community Plan • claps, housed elementary school students for Independ ence Day. But, as the story goes, Back Cover 75 years. In 1951, the school became a ware- organizers were concerned that no one would house, and from 1959 to 1966, it served as a come only to listen to speeches and awards, so teen center. After suggestions were made to it was decided to hold a 4th of July parade tear it down, an effort to save the schoolhouse at the same time with the theme “Honor formed. -

Ghouls, Dolls, and Girlhoods: Fashion and Horror at Monster High

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUScholarWorks Ghouls, Dolls, and Girlhoods: Fashion and Horror at Monster High Karen E. Wohlwend In Generation Z: Zombies, Popular Culture, and Educating Youth Edited by Victoria Carrington, Jennifer Rowsell, Esther Priyadharshini, Rebecca Westrup This is a preprint; the definitive version is in press at http://www.springer.com/us/ Wohlwend, K. E. (In press). Ghouls, dolls, and girlhoods: Fashion and horror at Monster High. In V. Carrington, J. Rowsell, E. Priyadharshini & R. Westrup (Eds.), Generation Z: Zombies, popular culture, and educating youth. New York: Springer. Girls, Ghouls, and Girlhoods: Horror and Fashion at Monster High Introduction How does a zombie doll in a popular horror franchise for tween girls serve as a productive site of contestation among overlapping visions of girlhood? In this chapter, I examine Ghoulia Yelps, a zombie character in the popular Monster High fashion doll franchise, not only as a toy in a global flow of licensed consumer goods but also as a site of identity construction and digital media production where facile notions of girlhoods are both enacted and reimagined (Forman- Brunell, 2012). Monster High is reconceptualized here as the site of converging cultural imaginaries (Medina & Wohlwend, 2014) in which children play in and out of gendered futures around fashion, adolescence, diversity, and schooling. Critical analysis of tween girls’ digital play with a zombie doll on social media reveals the resonances, slippages, and paradoxes among identity texts produced about, for, and by girls. After describing the scope of the Monster High franchise and how it materializes expectations for characters, consumers, and players, I next examine how these dolls and identity texts circulate three dominant imaginaries of girlhood. -

Kamaiyah Before I Wake Free Album Download

kamaiyah before i wake free album download zip Kamaiyah Surprises Fans With New Mixtape ‘Before I Wake’ With very little notice, Kamaiyah released a brand new mixtape, Before I Wake. Nearly two years after her debut effort, A Good Night in the Ghetto , this new project is packed with evocative Bay Area-inspired beats, as well as a variety of melodic flows. Kamaiyah Brings 90s Flair To Self-Love Anthem “Build You Up” The 10-track mixtape is featureless and is produced entirely by Link Up, the beatmaker responsible for Kam’s “Ain’t Going Home Tonight.” Earlier this year, the 25-year-old MC announced her official album, Don’t Get It Twisted . But the project has yet to come to fruition.This week, Kamaiyah spoke with GQ about Don’t Get it Twisted and Before I wake . “I’m working on putting out two projects, Before I Wake and Woke. Conceptualized! No features. All me,” Kam said to GQ . “I’m picking up my speed—the momentum I took a deficit toward.” She added: “Because my [major-label studio debut] has been held up due to samples. So it wasn’t put out on time. It was supposed to come out in March, I believe. Now it’s November. So to make up for that deficit, I’m gonna put out more work.” Stream Kamaiyah's "Before I Wake" Mixtape. Oakland rapper Kamaiyah surprises fans with a new 10-track mixtape called "Before I Wake." Well look what we have here. It’s been a minute since we last heard from Oakland’s own Kamiayah. -

Legacy-Project-Full.Pdf

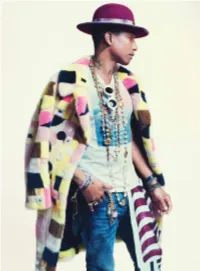

ÉTHE MUSIC WORLD IS STILL THE MOST INNOVATIVE, ENERGIZING, AND ECLECTIC SLICE OF THE AMERICAN- POP-CULTURE PIE. BUT WHAT ARTISTS SHOULD A MAN ACTUALLY BE LISTENING TO RIGHT NOW? AND WHO WILL WE STILL BE LISTENING TO TEN, TWENTY, AND EVEN FIFTY YEARS FROM NOW? AS THE 2015 GRAMMYS APPROACH, WE TAKE A LOOK AT THE MUSIC MAKERS WHO, THIS YEAR, LEFT SOMETHING LASTING BEHIND THE LEGACY PROJECT PORTFOLIO PARI DUKOVIC 02.15 GQ. COM 51 PHARRELL WILLIAMS THE MAN WHO NEVER SLEEPS Photographed at Mr. C hotel in Beverly Hills. Thirteen Hours Inside Pharrell Williams’s Relentless Pop- Culture Machine BY DEVIN FRIEDMAN 10:57 a.m. Uniqlo, West Hollywood WHEN PHARRELL arrives, it’s as if in a bubble. Like Glenda, the Good Witch of the North. Starbucks in one hand, two Asian-American women assistants trailing in his wake, a Chanel scarf waving from his back pocket. Uniqlo has closed this store, in the Beverly Center, for an event: About thirty homeless kids have been given a shopping spree. Pharrell Williams, who of course collaborates on a clothing line with Uniqlo, is the surprise guest. He takes a picture with a girl in a her royal smurfness T-shirt and checks out jeans with a kid in a Lakers jersey. Truth be told, a lot of these kids don’t seem to know who he is. Most 7-year-olds don’t even know what a celebrity is. They don’t know that this is the man who, not long ago, was responsible for 43 percent of songs played on the radio in a single month; they probably don’t watch The Voice, where Pharrell is a celebrity “coach”; they don’t listen to “Blurred Lines” and know, hey, the genius behind that song wasn’t Robin Thicke, it was longtime super-producer and current pop star Pharrell Williams; and they don’t know that his 2014 album, Girl, is up for an album- of-the-year Grammy. -

Nights Not Spent Alone

ALSO AVAILABLE... NIGHTS NOT SPENT ALONE 1 4 9 9 0 0 D D C C R R H H C C THIS OTHER EDEN: MENDELSSOHN: COMPLETE KITTY WHATELY SONGS VOL.2 A LANDSCAPE OF ENGLISH POETRY MALCOLM MARTINEAU & SONG Champs Hill Records is delighted to “This is a terrific debut disc from Kitty release the second volume in Malcolm Whately, a wonderfully satisfying recital, Martineau’s series presenting the complete beautifully sung and with poetry readings songs of Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn that are very fine.” alongside each other. The Classical Reviewer Showing the rich variety and distinctive “Her singing is excellent and expressive while voice of both composers, Martineau brings her care for the words – in every sense – is together a wealth of imaginative young exemplary. ” vocal talent in Sophie Bevan, Robin Musicweb International Tritschler, Jonathan McGovern, Mary Bevan, “Whately is a captivating live performer… Kitty Whately and Benjamin Appl. In an age of glossily interchangeable international artists, this one isn’t afraid “... the brilliant collaboration of Martineau, to tell us her story. I, for one, want to first-rate sound, and with enchanting hear more.” singing, this second volume is a KITTY WHATELY Gramophone thorough delight.” American Record Guide SIMON LEPPER FOREWORD I am so delighted to have been given the opportunity to return to the beautiful Champs Hill, and work with this fantastic team again to produce my second album. Having been a huge fan of Jonathan Dove's work for a long time, I was thrilled when BBC Radio 3 commissioned him to write me a song cycle during my time on their New Generation Artists scheme. -

BTS' 'Life Goes On' Launches As Historic No. 1 on Billboard Hot

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth NOVEMBERAirplay 30, 2020 Page 1 of 36 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE BTS’ ‘Life Goes On’ Launches as Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music GroupHistoric Nashville), debuts at No. 1 on No. Billboard’s 1lion on audience Billboard impressions, up 16%). Hot 100 Top• CountryBTS Earns Albums Fifth chartNo. dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned1 Album 46,000 on Billboardequivalent album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cording200 toChart Nielsen With Music/MRC ‘Be’ Data. and totalBY GARY Country TRUST Airplay No. 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends Southside marks Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chart• and Why fourth The Musictop 10. It followsBTS freshman’ “Life Goes LP On” soars onto the Billboard Hot ending Nov. 26,Young’s according first ofto six Nielsen chart entries,Music/MRC “Sleep With- Publishing Market Is Montevallo, which arrived at the summit songs in chart No - at No. 1. Data. It alsoout earned You,” 410,000 reached No.radio 2 in airplay December audience 2016. He Still Booming — And 100 vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks.The song To date, is the South Korean septet’s third Hot 100 impressionsfollowed in the week with the ending multiweek Nov. -

2018 Annual Report

TO OUR STOCKHOLDERS I am pleased to report that 2018 represented our 26th consecutive record year of increased gross sales. Net sales rose to $3.8 billion in 2018 from $3.4 billion in 2017. Gross sales rose to $4.4 billion in 2018 from $3.9 billion in 2017. We continue to innovate in the energy drink category and following successful launches earlier this year, we anticipate future introductions of new and exciting beverages and packaging. In particular, in March 2019, we successfully launched Reign Total Body Fuel™, our new line of performance energy drinks. In 2018 and 2019, we continued to transition a number of domestic and international geographies to the system bottlers of The Coca-Cola Company. Our Monster Energy® drinks are now sold in approximately 142 countries and territories globally and our Strategic Brands, comprised of various energy drink brands we acquired from The Coca-Cola Company in 2015, are now sold in approximately 96 countries and territories globally. One or more of our energy drinks are now distributed in approximately 155 countries and territories worldwide. Our Monster Energy® brand participates in the premium segment of the energy drink category in numerous countries as do our Strategic Brands. Our affordable energy brand, notably Predator®, participates in the affordable segment of the energy drink category internationally. Norman C. Epstein, Harold C. Taber, Jr. and Kathy N. Waller are retiring from the Board of Directors effective as of the 2019 Annual Meeting and are not standing for re-election. Mr. Epstein and Mr. Taber have both served on the Board of Directors since 1992, and Ms. -

The Debt Monster How Four Credit Counseling Agencies Used Human-Centered Design to Reach Consumers with Sustained Balances

The Debt Monster How Four Credit Counseling Agencies Used Human-Centered Design to Reach Consumers with Sustained Balances The Debt Monster How Four Credit Counseling Agencies Used Human-Centered Design to Reach Consumers with Sustained Balances AUTHORS: Ivan Avila, Stephanie Landry, Spectra Myers Acknowledgements We give thanks to the team of people who made this report possible. We are especially grateful to our partners at the Credit Counseling of Arkansas, Consumer Credit Counseling Service of Rochester, Consumer Credit Counseling Services of the Savannah Area, Inc. and OnTrack WNC Financial Education & Counseling for their engagement and support through all project components. Our colleagues at Prosperity Now, Pamela Chan, Emma Polson, Kasey Wiedrich and Guillermo Cantor, provided helpful feedback and guidance. Applied Research intern Jordan Beeker supported pilot data collection. We would also like to thank Sandiel Thornton, Lauren Treadwell and Ursula Cisneros for support in graphic design and campaign development. Sawyer Blur provided volunteer media planning support. Lastly, we’d like to extend our gratitude to MIQ for paid marketing support and Cornershop Creative for website design. This report was made possible with the generous support of Capital One. About Prosperity Now Prosperity Now believes that everyone deserves a chance to prosper. Since 1979, we have helped millions of people, especially people of color and those of limited incomes, to achieve financial security, stability and, ultimately, prosperity. We offer a unique combination of practical solutions, in-depth research and proven strategies, all aimed at building wealth for those who need it most. We recognize the devastating impact of the racial wealth divide on people and our economy, and we strive to equip organizations of color and others with the capacity, tools and cultural competency necessary to address structural and systemic barriers facing families of color. -

Sexual Violence in Popular Rap Music and Other Media

SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN POPULAR RAP MUSIC AND OTHER MEDIA Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors RAY , OLIVIA SUNDIATA Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 22:29:05 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/618766 SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN POPULAR RAP MUSIC AND OTHER MEDIA By OLIVIA SUNDIATA RAY A Thesis Submitted to the Honors College In Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelor’s Degree with Honors in Political Science THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA MAY 2016 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. Samara Klar School of Government and Public Policy Ray 2 Abstract This paper examines the prevalence of sexual violence in American media with particular focus on attitudes of sexual violence as a contribution to rape culture. Included is a content analysis of the prevalence of sexually violent lyrics in popular rap music, and a literature review of articles and studies on the effects of sexually violent media. The media discussed in the literature review includes films, television, and pornography. The relationship between the presence of sexually violent media and its impact on public opinion on sexual assault and rape proclivity are analyzed. The literature reviewed includes studies on differences in response to sexually violent media based on gender. Also included are explanation and summary of a study utilizing the excitation transfer theory and the social learning theory as they apply to the understanding of the perpetuation of rape myth acceptance based in the viewing of sexually violent media.