NOTE T B USERS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2005-419-1

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2005-419-1 Ottawa, 28 September 2005 CHUM Limited Victoria, British Columbia Erratum 1. Paragraph 1 of Complaint regarding the broadcast of an episode of Talk Radio on CFAX, Victoria, Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2005-419, 18 August 2005, is replaced with the following, which clarifies that CHUM Limited, the current licensee of CFAX, was not the licensee at the time that the programming addressed in the decision was broadcast: 1. On 11 October 2004, the Commission received a written complaint concerning a segment of programming broadcast on 27 September 2004 by CFAX, an AM radio station in Victoria, British Columbia. On 3 September 2004, the Commission approved, subject to conditions precedent, an application by CHUM Limited (CHUM) to acquire from Seacoast Communications Group Inc. (Seacoast) the assets of CFAX and CHBE-FM Victoria, and for broadcasting licences to continue the operation of the stations.1 The conditions precedent were satisfied on 29 September 2004. Seacoast was therefore still the licensee of CFAX at the time of the broadcast in question. In light of the above, the references to “the licensee” in paragraphs 20 and 26 are to Seacoast and all other references to “the licensee,” including those in paragraph 27, are to CHUM, the current licensee that replied to the complaint. 2. The italicized summary at the beginning of the decision is replaced with the following, so that it accurately reflects the body of the decision. In this decision, the Commission addresses a complaint regarding comments that were broadcast by CFAX, an AM radio station in Victoria. -

FACTOR 2006-2007 Annual Report

THE FOUNDATION ASSISTING CANADIAN TALENT ON RECORDINGS. 2006 - 2007 ANNUAL REPORT The Foundation Assisting Canadian Talent on Recordings. factor, The Foundation Assisting Canadian Talent on Recordings, was founded in 1982 by chum Limited, Moffat Communications and Rogers Broadcasting Limited; in conjunction with the Canadian Independent Record Producers Association (cirpa) and the Canadian Music Publishers Association (cmpa). Standard Broadcasting merged its Canadian Talent Library (ctl) development fund with factor’s in 1985. As a private non-profit organization, factor is dedicated to providing assistance toward the growth and development of the Canadian independent recording industry. The foundation administers the voluntary contributions from sponsoring radio broadcasters as well as two components of the Department of Canadian Heritage’s Canada Music Fund which support the Canadian music industry. factor has been managing federal funds since the inception of the Sound Recording Development Program in 1986 (now known as the Canada Music Fund). Support is provided through various programs which all aid in the development of the industry. The funds assist Canadian recording artists and songwriters in having their material produced, their videos created and support for domestic and international touring and showcasing opportunities as well as providing support for Canadian record labels, distributors, recording studios, video production companies, producers, engineers, directors– all those facets of the infrastructure which must be in place in order for artists and Canadian labels to progress into the international arena. factor started out with an annual budget of $200,000 and is currently providing in excess of $14 million annually to support the Canadian music industry. Canada has an abundance of talent competing nationally and internationally and The Department of Canadian Heritage and factor’s private radio broadcaster sponsors can be very proud that through their generous contributions, they have made a difference in the careers of so many success stories. -

VIZEUM CANADA INC. Suite 1205, Oceanic Plaza, 1066 West Hastings Vancouver BC V6E 3X1 (604) 646-7282

VIZEUM CANADA INC. Suite 1205, Oceanic Plaza, 1066 West Hastings Vancouver BC V6E 3X1 (604) 646-7282 NEWSPAPER CLIENT: Ministry of Finance PUBLICATION NET TOTAL BC DAILIES VANCOUVER - LOWER MAINLAND VANCOUVER SUN $138,495.90 VANCOUVER PROVINCE $71,257.50 NORTHERN BC DAWSON CREEK DAILY NEWS $10,002.00 FORT ST. JOHN ALASKA HWY NEWS $10,502.10 PRINCE GEORGE CITIZEN $14,473.70 THE ISLAND ALBERNI VALLEY TIMES $9,671.06 NANAIMO DAILY NEWS $12,195.40 VICTORIA TIMES COLONIST $53,158.10 THOMPSON OKANAGAN KAMLOOPS DAILY NEWS $17,269.10 KELOWNA DAILY COURIER $17,362.80 PENTICTON HERALD $15,403.70 KOOTENAY ROCKIES CRANBROOK DAILY TOWNSMAN $7,518.00 KIMBERLEY DAILY BULLETIN $6,489.60 TRAIL DAILY TIMES $9,905.70 NATIONAL DAILY GLOBE AND MAIL - BC EDITION $37,414.42 FREE DAILIES 24 HOURS $39,004.00 METRO VANCOUVER $33,690.00 Page 1 Page 1 of 9 FIN-2011-00084 VIZEUM CANADA INC. Suite 1205, Oceanic Plaza, 1066 West Hastings Vancouver BC V6E 3X1 (604) 646-7282 BC COMMUNITIES VANCOUVER - LOWER MAINLAND BURNABY NOW $13,102.80 BURNABY/ NEW WEST NEWS LEADER $20,374.20 COQ/PT COQ/PT MOODY TRI-CITY NEWS $17,331.30 COQUITLAM NOW $13,102.80 DELTA OPTIMIST $8,269.80 DELTA, SOUTH DELTA LEADER $4,709.60 LANGLEY ADVANCE $9,753.54 LANGLEY TIMES $14,685.30 MAPLE RIDGE / PITT MEADOWS NEWS $11,778.20 MAPLE RIDGE / PITT MEADOWS TIMES $8,919.90 NEW WESTMINSTER, THE RECORD $8,549.04 RICHMOND NEWS $14,515.20 RICHMOND REVIEW $15,019.20 SURREY / NORTH DELTA LEADER $22,491.00 SURREY NOW $18,505.80 VANCOUVER COURIER - ALL $45,090.00 VANCOUVER WESTENDER $10,399.90 WHITE ROCK PEACE ARCH NEWS $13,097.70 BUSINESS IN VANCOUVER $6,392.00 VANCOUVER - FRASER VALLEY ABBOTSFORD / MISSION TIMES $11,175.00 ABBOTSFORD NEWS (Abbotsford & Mission) $18,144.00 AGASSIZ-HARRISON OBSERVER $2,248.40 ALDERGROVE STAR $3,219.30 CHILLIWACK PROGRESS $14,778.40 CHILLIWACK TI MES $9,565.80 HOPE STANDARD $3,014.90 MISSION RECORD $4,036.90 Page 2 Page 2 of 9 FIN-2011-00084 VIZEUM CANADA INC. -

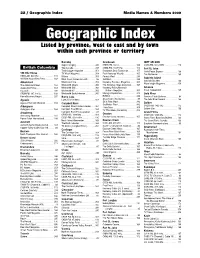

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Submission of Renewal Applications for Broadcasting Licences of Radio Stations Expiring 31 August 2020

Broadcasting Notice of Consultation CRTC 2019-194 PDF version Ottawa, 3 June 2019 Public record: 1011-NOC2019-0194 Call for licence renewal applications Submission of renewal applications for broadcasting licences of radio stations expiring 31 August 2020 1. The Commission requests that the licensees listed in the appendix to this notice submit renewal applications for their broadcasting licences expiring 31 August 2020. The licensees must submit their renewal applications by no later than 31 August 2019. 2. Licensees who do not wish to renew their licences beyond the expiry date indicated in this notice must advise the Commission in writing by no later than 31 August 2019. 3. This call for applications is consistent with the procedures announced in New procedures for licence renewal applications, Broadcasting Information Bulletin CRTC 2015-116, 31 March 2015 (Broadcasting Information Bulletin 2015-116). 4. The Commission will process the licence renewal applications under the rules for applications set out in Part 1 of the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Rules of Practice and Procedure. However, where the Commission deems appropriate, the renewal applications may be published in a notice of consultation. 5. Interested persons will be given the opportunity to comment on the renewal applications once they are posted on the Commission’s website. Procedure for filing 6. Licensees must file their renewal applications electronically by completing the Broadcasting Online Form and Cover Page using the secured service My CRTC Account (Partner Log In or GCKey Log In). An example of the application form can be viewed on the web page Radio – Licence Renewal – Form 310. -

Vividata Brands by Category

Brand List 1 Table of Contents Television 3-9 Radio/Audio 9-13 Internet 13 Websites/Apps 13-15 Digital Devices/Mobile Phone 15-16 Visit to Union Station, Yonge Dundas 16 Finance 16-20 Personal Care, Health & Beauty Aids 20-28 Cosmetics, Women’s Products 29-30 Automotive 31-35 Travel, Uber, NFL 36-39 Leisure, Restaurants, lotteries 39-41 Real Estate, Home Improvements 41-43 Apparel, Shopping, Retail 43-47 Home Electronics (Video Game Systems & Batteries) 47-48 Groceries 48-54 Candy, Snacks 54-59 Beverages 60-61 Alcohol 61-67 HH Products, Pets 67-70 Children’s Products 70 Note: ($) – These brands are available for analysis at an additional cost. 2 TELEVISION – “Paid” • Extreme Sports Service Provider “$” • Figure Skating • Bell TV • CFL Football-Regular Season • Bell Fibe • CFL Football-Playoffs • Bell Satellite TV • NFL Football-Regular Season • Cogeco • NFL Football-Playoffs • Eastlink • Golf • Rogers • Minor Hockey League • Shaw Cable • NHL Hockey-Regular Season • Shaw Direct • NHL Hockey-Playoffs • TELUS • Mixed Martial Arts • Videotron • Poker • Other (e.g. Netflix, CraveTV, etc.) • Rugby Online Viewing (TV/Video) “$” • Skiing/Ski-Jumping/Snowboarding • Crave TV • Soccer-European • Illico • Soccer-Major League • iTunes/Apple TV • Tennis • Netflix • Wrestling-Professional • TV/Video on Demand Binge Watching • YouTube TV Channels - English • Vimeo • ABC Spark TELEVISION – “Unpaid” • Action Sports Type Watched In Season • Animal Planet • Auto Racing-NASCAR Races • BBC Canada • Auto Racing-Formula 1 Races • BNN Business News Network • Auto -

NUMERIS Top-Line Radio Statistics Fall 2018 September 3–October 28, 2018 TOP-LINE RADIO STATISTICS St

NUMERIS Top-line Radio Statistics Fall 2018 September 3–October 28, 2018 TOP-LINE RADIO STATISTICS St. John's CTRL Source: Numeris Survey Period: Radio Diary Survey September 3 - October 28, 2018 Demographic: A12+ Area: 0009 (St. John's Ctrl) Daypart: Monday-Sunday 5am-1am Fall 2018 Universe: 194,920 Station Market Share % Ctrl Reach (000) FC Reach (000) CBN St John's Ctrl 12.0 42.4 60.0 CBN FM St John's Ctrl 2.6 13.1 21.2 CHOZF+ St John's Ctrl 5.7 50.6 133.2 CJYQ St John's Ctrl 0.4 4.2 7.2 CKIXFM St John's Ctrl 10.7 59.6 73.8 CKSJFM St John's Ctrl 15.4 61.1 84.5 VOCM St John's Ctrl 20.2 63.8 124.3 VOCMFM St John's Ctrl 19.6 65.5 96.1 TERMS Central (Ctrl) Market Area - A Numeris defined geographical area, usually centred around one urban centre. The definition of a Central Market Area generally corresponds to Statistics Canada Census Metropolitan Areas, Census Agglomeration, Cities, Counties, Census Divisions or Regional Districts. Universe - Estimated Population of the Central Market Area. Share - Within the central market area, the estimated total hours tuned to that station expressed as a percentage of total hours tuned to all radio. Central (Ctrl) Reach - The estimated number of different people, within the central market area, who tuned to that station for at least one quarter hour during the week. Full Coverage (FC) Reach - The estimated number of different people, anywhere in Canada, who tuned to that station for at least one quarter hour during the week. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

Federal Court Final Settlement Agreement

FEDERAL COURT Proposed Class Proceedings Court File No.: T-2111-16 SHERRY HEYDER, AMY GRAHAM and NADINE SCHULTZ-NIELSEN Plaintiffs - and - THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA Defendant Court File No.: T-460-17 LARRY BEATTIE Plaintiff - and - THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA Defendant FINAL SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT WHEREAS: A. Some members of the Canadian Armed Forces ("CAF") have experienced sexual harassment, sexual assault, and/or discrimination on the grounds of sex, gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in connection with their military service; B. Some public service employees appointed under the Public Service Employment Act to positions in the Department of National Defence (“DND”), and some employees of the Staff of the Non-Public Funds, Canadian Forces (“SNPF”), have also experienced sexual Page 1 of 280 harassment, sexual assault, and/or discrimination on the grounds of sex, gender, gender identity or sexual orientation in connection with their employment in the Military Workplace; C. In 2016 and 2017, proposed class proceedings were commenced against Canada in the Federal Court of Canada, the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia, the British Columbia Superior Court, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice and the Quebec Superior Court in connection with this Sexual Misconduct. Those proceedings have been stayed on consent or by order, or have been held in abeyance, while this proposed class action by Sherry Heyder, Amy Graham and Nadine Schultz-Nielsen (the “Heyder Class Action”), and this proposed class action by Larry Beattie (the “Beattie Class Action”), have been pursued together in the Federal Court (together, the “Heyder and Beattie Class Actions”) on behalf of all four representative plaintiffs (together, the “Plaintiffs”). -

Various Radio and Television Stations – Corporate Reorganization

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2019-14 PDF version Reference: 2018-388 Ottawa, 21 January 2019 Bell Media Inc., on its own behalf and on behalf of 8384819 Canada Inc., and Bell Media Inc., on behalf of a corporation to be incorporated Various locations Public record for these applications: 2018-0483-1, 2018-0672-0, 2018-0673-8, 2018-0674-6, 2018-0675-4, 2018-0676-2 and 2018-0484-9 Public hearing in the National Capital Region 6 December 2018 Various radio and television stations – Corporate reorganization 1. The Commission approves the applications by Bell Media Inc. (Bell Media), on its own behalf and on behalf of 8384819 Canada Inc., as well as the application by Bell Media, on behalf of a corporation to be incorporated, for authority to effect a multi- step corporate reorganization involving the assets of the radio and television services listed in the appendix to this decision. Bell Media also requested new broadcasting licences to continue the operation of these services under the same terms and conditions as those in effect under the current licences. The Commission did not receive any interventions regarding these applications. 2. The corporate reorganization will be effected through a series of steps. First, a new share capital corporation will acquire the assets of the services currently operated by Bell Media Radio (Toronto) Inc. and 4382072 Canada Inc., partners in a general partnership carrying on business as Bell Media Radio G.P. Following an amalgamation, Bell Media will become the licensee of these undertakings. Next, Bell Media and 8384819 Canada Inc. will become partners in a new general partnership, which will replace the general partnerships currently carrying on business as Bell Media Windsor Radio Partnership, Bell Media Ontario Regional Radio Partnership, Bell Media Ottawa Radio Partnership, Bell Media Toronto Radio 2013 Partnership, Bell Media Canada Radio 2013 Partnership and Bell Media British Columbia Radio Partnership. -

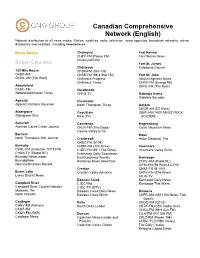

Get Maximum Exposure to the Largest Number of Professionals in The

Canadian Comprehensive Network (English) National distribution to all news media. Dailies, weeklies, radio, television, news agencies, broadcast networks, online databases and websites, including newswire.ca. News Media Chetwynd Fort Nelson CHET-FM [Peace FM] Fort Nelson News Chetwynd Echo British Columbia Fort St. James Chilliwack Caledonia Courier 100 Mile House CFSR-FM (Star FM) CKBX-AM CKSR-FM (98.3 Star FM) Fort St. John CKWL-AM [The Wolf] Chilliwack Progress Alaska Highway News Chilliwack Times CHRX-FM (Energy 98) Abbotsford CKNL-FM (The Bear) CKQC-FM Clearbrook Abbotsford/Mission Times CFEG-TV Gabriola Island Gabriola Sounder Agassiz Clearwater Agassiz Harrison Observer North Thompson Times Golden CKGR-AM [EZ Rock] Aldergrove Coquitlam CKIR-AM [1400 AM EZ ROCK Aldergrove Star Now, The GOLDEN] Ashcroft Courtenay Hagensborg Ashcroft Cache Creek Journal CKLR-FM (The Eagle) Coast Mountain News Comox Valley Echo Barriere Hope North Thompson Star Journal Cranbrook Hope Standard, The CHBZ-FM (B104) Burnaby CHDR-FM (The Drive) Invermere CFML-FM (Evolution 107.9 FM) CJDR-FM (99.1 The Drive) Invermere Valley Echo CHAN-TV (Global BC) Cranbrook Daily Townsman Burnaby NewsLeader East Kootenay Weekly Kamloops BurnabyNow Kootenay News Advertiser CHNL-AM (Radio NL) New Westminster Record CIFM-FM (98 Point 3 CIFM) Creston CKBZ-FM (B-100) Burns Lake Creston Valley Advance CKRV-FM (The River) Lakes District News CFJC-TV Dawson Creek Kamloops Daily News Campbell River CJDC-AM Kamloops This Week Campbell River Courier-Islander CJDC-TV (NTV) Midweek, -

Ownership Chart 143N

BCE Bell Media Radio & TV #143n Ownership – Broadcasting - CRTC 2021-01-15 UPDATE CRTC 2018-57 – approved the acquisition by Bell Media Inc. of the assets of CICZ-FM Midland, CICX-FM Orillia, CJOS-FM Owen Sound and CICS-FM Sudbury from Larche Communications Inc. CRTC 2019-14 - approved a multi-step corporate reorganization effected through: 1. The acquistion by a new share capital corporation of the assets of the services currently operated by Bell Media Radio (Toronto) Inc. and 4382072 Canada Inc., partners in a general partnership carrying on business as Bell Media Radio G.P. Afterwards, an amalgamation will occur and Bell Media Inc. will become the licensee of the undertakings. 2. Bell Media Inc.and 8384819 Canada Inc. will become partners in a new general partnership, which will replace the general partnerships currently carrying on business as Bell Media Windor Radio Partnership, Bell Media Ontario Regional Radio Partnership, Bell Media Ottawa Radio Partnership, Bell Media Toronto Radio 2013 Partnership, Bell Media Canada Radio 2013 Partnership and Bell Media British Columbia Radio Partnership. CRTC 2020-116 & CRTC 2020-154 – amalgamation of Groupe V Média inc. with its subsidiary V Interactions inc. to form a corporation, the name of which is to be determined (VFusion). After the amalgamation, all of the issued and outstanding shares of VFusion held by Remstar and other shareholders will be transferred to Bell Canada. Afterwards, Bell Canada will transfer all of the shares of VFusion to Bell Media Inc. NOTE: These ownership changes were reflected. Update – 2020-04-14 – incorporation of 11749366 Canada Inc.