Evidence from Erbil Citadel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archaeology of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and Adjacent Regions

Copyrighted material. No unauthorized reproduction in any medium. The Archaeology of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and Adjacent Regions Edited by Konstantinos Kopanias and John MacGinnis Archaeopress Archaeology Copyrighted material. No unauthorized reproduction in any medium. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 393 9 ISBN 978 1 78491 394 6 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the authors 2016 Cover illustration: Erbil Citadel, photo Jack Pascal All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Holywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Copyrighted material. No unauthorized reproduction in any medium. Contents List of Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................................iv Authors’ details ..................................................................................................................................... xii Preface ................................................................................................................................................. xvii Archaeological investigations on the Citadel of Erbil: Background, Framework and Results.............. 1 Dara Al Yaqoobi, Abdullah Khorsheed Khader, Sangar Mohammed, Saber -

Substance Use Among High School Students in Erbil City, Iraq: Prevalence and Potential Contributing Factors

Research article EMHJ – Vol. 25 No. 11 – 2019 Substance use among high school students in Erbil City, Iraq: prevalence and potential contributing factors Nazar Mahmood,1 Samir Othman,1 Namir Al-Tawil 1 and Tariq Al-Hadithi1 1Department of Community Medicine, College of Medicine, Hawler Medical University-Erbil, Kurdistan Region, Iraq (Correspondence to: Nazar A. Mahmood: [email protected]). Abstract Background: Substance use among adolescents, especially smoking and alcohol consumption, has become a public health concern in the Kurdistan Region, Iraq, in the past 10 years. Aims: This study aimed to determine the prevalence of substance use and certain associated factors among high school students in Erbil City, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted using a multistage cluster sampling technique to collect a sample of 3000 students. A modified version of the School Survey on Drug Use from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime was used for data collection. Binary logistic regression models were used to identify risk factors for substance use. Results: The lifetime prevalence rates of cigarettes smoking, waterpipe smoking and alcohol consumption were 27.6%, 23.6% and 3.7%, respectively. Male gender, age 17–19 years, smoker in the family, and easy accessibility of cigarettes were significantly associated with cigarette smoking. Factors significantly associated with waterpipe smoking were male gen- der, age 17–19 years, waterpipe smoker in the family, waterpipe smoker friend, and easy accessibility. Male gender, alco- hol dependent in the family, alcohol-dependent friend, easy accessibility of alcohol, and low family income were signifi- cant predictors of alcohol consumption. -

Freedom of Expression in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

@ Metro Centre; Hevi Khalid (Sulaymaniyah December 2020) Freedom of Expression in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights May 2021 Baghdad, Iraq “Recent years have seen progress towards a democratic Kurdistan Region where freedom of expression and the rule of law are valued. But democratic societies need media, activists and critics to be able to report on public issues without censorship or fear, and citizens also have a right to be informed.” - UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet, 12 May 2021 “Transparency, accountability and openness to questioning is vital for any healthy democracy.” - Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Iraq, Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert, 12 May 2021 2 Contents I. Executive summary ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 II. Mandate ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 III. Methodology ................................................................................................................................................................. 5 IV. Legal Framework .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 i. Applicable International -

Babylonian Populations, Servility, and Cuneiform Records

Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 60 (2017) 715-787 brill.com/jesh Babylonian Populations, Servility, and Cuneiform Records Jonathan S. Tenney Cornell University [email protected] Abstract To date, servility and servile systems in Babylonia have been explored with the tradi- tional lexical approach of Assyriology. If one examines servility as an aggregate phe- nomenon, these subjects can be investigated on a much larger scale with quantitative approaches. Using servile populations as a point of departure, this paper applies both quantitative and qualitative methods to explore Babylonian population dynamics in general; especially morbidity, mortality, and ages at which Babylonians experienced important life events. As such, it can be added to the handful of publications that have sought basic demographic data in the cuneiform record, and therefore has value to those scholars who are also interested in migration and settlement. It suggests that the origins of servile systems in Babylonia can be explained with the Nieboer-Domar hy- pothesis, which proposes that large-scale systems of bondage will arise in regions with * This was written in honor, thanks, and recognition of McGuire Gibson’s efforts to impart a sense of the influence of aggregate population behavior on Mesopotamian development, notably in his 1973 article “Population Shift and the Rise of Mesopotamian Civilization”. As an Assyriology student who was searching texts for answers to similar questions, I have occasionally found myself in uncharted waters. Mac’s encouragement helped me get past my discomfort, find the data, and put words on the page. The necessity of assembling Mesopotamian “demographic” measures was something made clear to me by the M.A.S.S. -

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq

WELCOME TO THE KURDISTAN REGION OF IRAQ Contents President Masoud Barzani 2 Fast facts about the Kurdistan Region of Iraq 3 Overview of the Kurdistan Region 4 Key historical events through the 19th century 9 Modern history 11 The Peshmerga 13 Religious freedom and tolerance 14 The Newroz Festival 15 The Presidency of the Kurdistan Region 16 Structure of the KRG 17 Foreign representation in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq 20 Kurdistan Region - an emerging democracy 21 Focus on improving human rights 23 Developing the Region’s Energy Potential 24 Kurdistan Region Investment Law 25 Tremendous investment opportunities beckon 26 Tourism potential: domestic, cultural, heritage 28 and adventure tourism National holidays observed by 30 KRG Council of Ministers CONTENTS Practical information for visitors to the Kurdistan Region 31 1 WELCOME TO THE KURDISTAN REGION OF IRAQ President Masoud Barzani “The Kurdistan Region of Iraq has made significant progress since the liberation of 2003.Through determination and hard work, our Region has truly become a peaceful and prosperous oasis in an often violent and unstable part of the world. Our future has not always looked so bright. Under the previous regime our people suffered attempted We are committed to being an active member of a federal, genocide. We were militarily attacked, and politically and democratic, pluralistic Iraq, but we prize the high degree of economically sidelined. autonomy we have achieved. In 1991 our Region achieved a measure of autonomy when Our people benefit from a democratically elected Parliament we repelled Saddam Hussein’s ground forces, and the and Ministries that oversee every aspect of the Region’s international community established the no-fly zone to internal activities. -

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya About MERI The Middle East Research Institute engages in policy issues contributing to the process of state building and democratisation in the Middle East. Through independent analysis and policy debates, our research aims to promote and develop good governance, human rights, rule of law and social and economic prosperity in the region. It was established in 2014 as an independent, not-for-profit organisation based in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Middle East Research Institute 1186 Dream City Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq T: +964 (0)662649690 E: [email protected] www.meri-k.org NGO registration number. K843 © Middle East Research Institute, 2017 The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of MERI, the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publisher. The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict MERI Policy Paper Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya October 2017 1 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................4 2. “Reconciliation” after genocide .........................................................................................................5 -

Transformation of Erbil Old Town Fabric Asmaa Ahmed Mustafa Jaff

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 10, Issue 3, March-2019 443 ISSN 2229-5518 Transformation of Erbil Old Town Fabric Asmaa Ahmed Mustafa Jaff Abstract— The historical cities in a time change with different factors. Like population growth, economical condition, social unconscious as can be listed many reasons. Erbil the capital located in the north of Iraq, a historic city. The most important factor in the planning and urban development of the city, and it was the focus point in the radial development of the city and iconic element is old town Erbil was entered on the World Heritage Sites (UNESCO) in 2014. In order to preserve and rehabilitation of the old historical city and conservation this heritage places and transfer for future generation and to prevent the loss of the identity of the city. This research focusing on the heritage places in the city and historical buildings, identifying the city, also the cultural and architectural characteristic. Cities are a consequence of the interaction of cultural, social, economic and physical forces. Countries have to adapt to these social, economic, physical and cultural changes, urban problems in order to meet the new needs and urban policies. Urban transformations, economic activity, social urban spaces that have lost their functions and physical qualities. This thesis study reveals the spatial and socio-economic effects of urban transformation. Historical Erbil city, which is the urban conservation project, was selected as the study area and the current situation, spatial and socio-economic effects of the urban transformation project being implemented in this region were evaluated. -

Fighting-For-Kurdistan.Pdf

Fighting for Kurdistan? Assessing the nature and functions of the Peshmerga in Iraq CRU Report Feike Fliervoet Fighting for Kurdistan? Assessing the nature and functions of the Peshmerga in Iraq Feike Fliervoet CRU Report March 2018 March 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: Peshmerga, Kurdish Army © Flickr / Kurdishstruggle Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the author Feike Fliervoet is a Visiting Research Fellow at Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit where she contributes to the Levant research programme, a three year long project that seeks to identify the origins and functions of hybrid security arrangements and their influence on state performance and development. -

Employment Promotion 4.0

Implemented by : Employment Promotion 4.0 Information & Communication Technologies (ICT) for a Modern Youth in Iraq The challenge are supported by experienced mentors in developing their busi- ness ideas. The trainings focus on practice-oriented skills in ICT, entrepreneurship and soft skills, and improve the overall employ- Iraq's population is one of the youngest in the world. Almost two ability of young Iraqis. Therefore, employment prospects are cre- thirds of all Iraqis are under the age of 25, many of whom are in- ated for both entrepreneurs and job seekers. ternally displaced persons in their own country, or refugees from neighbouring countries. The majority has hardly any employment Project Name ICT – Perspectives for the Modern Youth in Iraq prospects; every fifth of them is unemployed. Commissioned German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation Job opportunities in the traditional sectors of the Iraqi economy, by and Development (BMZ) such as the oil industry and public services, are decreasing. More than half of the working population is currently employed in the Project Region Baghdad, Basra, Mosul, Erbil, Sulaymaniyah, Anbar public sector, but with decreasing government revenues due to National Partner Ministry of Planning, Iraq declining oil prices, these jobs don’t offer long-term perspectives. Duration 12/2017 – 11/2020 The private sector, however, has hardly developed until now. Young Iraqis are becoming increasingly interested in the field of Furthermore, the matchmaking process between the supply and information and communication technologies (ICT) as a possible demand side on the ICT market is an integral part of the project. field of employment. The basic requirements for this sector are Access to finance and investments is a major burden for startups comparatively good in Iraq: Mobile Internet in broadband quality and their growth prospects. -

How to Respond to an Iraqi Militia Outrage by Michael Knights

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 3435 Rockets over Erbil: How to Respond to an Iraqi Militia Outrage by Michael Knights Feb 16, 2021 Also available in Arabic / Farsi ABOUT THE AUTHORS Michael Knights Michael Knights is the Boston-based Jill and Jay Bernstein Fellow of The Washington Institute, specializing in the military and security affairs of Iraq, Iran, and the Persian Gulf states. Brief Analysis Iran-backed militias took the unprecedented step of rocketing a major city and U.S. base in Iraqi Kurdistan, and the Biden administration must quickly find its own formula for restoring deterrence. n February 15, the city of Erbil (the capital of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, or KRI) was struck with a heavy O rocket attack that killed one contractor working for the U.S.-led coalition at Erbil’s airport, wounded five more coalition personnel (including one U.S. soldier), and injured at least three local civilians. As many as twenty- eight rocket launches may have been attempted, with more than a dozen rockets landing in the densely populated city, an unprecedentedly reckless strafing of a civilian population center. Despite efforts to muddy the waters by using “facade” groups to claim responsibility for the attack, Iran-backed militias are likely responsible, given their patterns of publicizing previous attacks. The Biden administration now has the difficult task of crafting a response that is measured but resolute, and must make some key decisions about how to attribute and deter such attacks on U.S. persons and U.S. partners in the future. The Erbil Rocket Attack A t 21.15 hours (Erbil time), a barrage of 107 mm rockets was fired from a disguised launch vehicle outside an agricultural market five miles southwest of Erbil. -

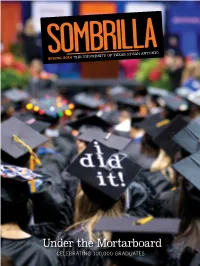

Under the Mortarboard

SombrillaSPRING 2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT SAN ANTONIO Under the Mortarboard CELEBRATING 100,000 G RADUATES ON THE COVER: One of the thousands of recent UTSA graduates dis- plays her excitement on her mortarboard at the fall 2013 ceremony. COVER PHOTO: MARK MCCLENDON ON THIS PAGE: Students celebrate at the fall 2013 commencement. © EDWARD A. ORNELAS/SAN ANTONIO EXPRESS-NEWS/ZUMAPRESS.COM inSiDe Kicking It A simulator designed by UTSA students boils 12 down the science of football’s perfect kick. Under the Mortarboard Decorating mortarboards has become an unofficial highlight of commencement. As UTSA celebrates 100,000 graduates, meet the individuals behind some of the ceremony’s 16 unique mortarboard stories. Saving the Past In Iraq, two UTSA professors have joined 24 the effort to preserve ancient sites. The PaSeo CommuniTy TEACHING LET THE WORD 28 BIG UNIVERSITY’S 4 OUR FUTURE 8 GO FORTH SMALL START The teachers and Professor Ethan Get to know a few of faculty at Forester Wickman turns a the first to graduate Elementary exem- president’s words in 1974. plify the education into music. pipeline. 30 TRUCKIN’ 10 LET’S CIRCLE It TOMATO UNLOCKING One San Antonio UTSA alum Shaun 6 THE CLOUD middle school is Lee brings the farm- Cutting-edge tech- working with UTSA ers market to you. nologies come and UT Austin to UTSA. to change how 31 CLASS NOTES students are disci- Profile of commu- 7 ROWDY CENTS plined. nication studies Students can learn trailblazer Dariela money manage- ROADRUNNER Rodriguez ’00, M.A. ment techniques 14 SPORTS ’08; and Generations with this free Sports briefs; plus Federal Credit Union program. -

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq As a Violation Of

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq as a Violation of Human Rights Submission for the United Nations Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights About us RASHID International e.V. is a worldwide network of archaeologists, cultural heritage experts and professionals dedicated to safeguarding and promoting the cultural heritage of Iraq. We are committed to de eloping the histor! and archaeology of ancient "esopotamian cultures, for we belie e that knowledge of the past is ke! to understanding the present and to building a prosperous future. "uch of Iraq#s heritage is in danger of being lost fore er. "ilitant groups are ra$ing mosques and churches, smashing artifacts, bulldozing archaeological sites and illegall! trafficking antiquities at a rate rarel! seen in histor!. Iraqi cultural heritage is suffering grie ous and in man! cases irre ersible harm. To pre ent this from happening, we collect and share information, research and expert knowledge, work to raise public awareness and both de elop and execute strategies to protect heritage sites and other cultural propert! through international cooperation, advocac! and technical assistance. R&SHID International e.). Postfach ++, Institute for &ncient Near -astern &rcheology Ludwig-Maximilians/Uni ersit! of "unich 0eschwister-Scholl/*lat$ + (/,1234 "unich 0erman! https566www.rashid-international.org [email protected] Copyright This document is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution .! International license. 8ou are free to copy and redistribute the material in an! medium or format, remix, transform, and build upon the material for an! purpose, e en commerciall!. R&SHI( International e.). cannot re oke these freedoms as long as !ou follow the license terms.