Municipal Revenue Generation in the Calgary and Edmonton Metropolitan Regions and Its Implications for Land Use*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calgary Metropolitan Plan Environment Report: Strategies and Actions: Part 1

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Richard Parker Professorship Repository Calgary Regional Partnership Documents 2009 Calgary Metropolitan Plan Environment Report: Strategies and Actions: Part 1 O2 Planning + Design Inc. O2 Planning + Design Inc. Calgary Regional Partnership. (2009). Calgary Metropolitan Plan Environment Report: Strategies and Actions: Part 1. Calgary: O2 Planning + Design Inc. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/107163 report Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca CALGARY METROPOLITAN PLAN ENVIRONMENT REPORT: STRATEGIES AND ACTIONS Presented to: CALGARY REGIONAL PARTNERSHIP Presented by: O2 PLANNING + DESIGN INC. 2009 October 2010 Version Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction........................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 Existing Environment ............................................................................................................ 8 2.1 Land ................................................................................................................................. 8 2.1.1 Natural Regions and Subregions............................................................................. 8 2.1.2 Landforms .............................................................................................................. 12 2.1.3 Landscape Units .................................................................................................... 14 2.1.4 Vegetation and Land Cover .................................................................................. -

Annual Information Form May 18, 2000 2

WELL SERVICE LTD. Revised Annual Information Form May 18, 2000 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page THE COMPANY ................................................................... 2 BUSINESS OF THE COMPANY .......................................................... 2 Overview ................................................................. 2 History ................................................................... 3 Acquisition of Superior Oilwell Cementers Inc. ..................................... 4 Acquisition of Northline Energy Services Inc. ...................................... 4 Well Servicing Operations ..................................................... 4 Future Plans ............................................................... 5 SELECTED FINANCIAL INFORMATION ................................................... 6 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS ............................................. 7 ENVIRONMENTAL MATTERS .......................................................... 7 DIRECTORS AND OFFICERS ........................................................... 7 DIVIDEND RECORD AND POLICY ...................................................... 10 MARKET FOR COMMON SHARES OF THE COMPANY ....................................... 10 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ......................................................... 10 THE COMPANY Trican Well Service Ltd. (“Trican” or the “Company”) was incorporated under the Companies Act (Alberta) on April 11, 1979 under the name 216858 Oilwell Service Co. Ltd. The Company’s name was changed to Trican Oilwell -

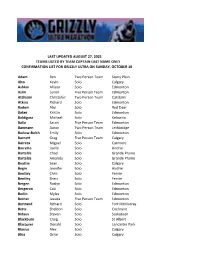

Last Updated August 27, 2021 Teams Listed by Team Captain Last Name Only Confirmation List for Grizzly Ultra on Sunday, October 10

LAST UPDATED AUGUST 27, 2021 TEAMS LISTED BY TEAM CAPTAIN LAST NAME ONLY CONFIRMATION LIST FOR GRIZZLY ULTRA ON SUNDAY, OCTOBER 10 Adam Ben Two Person Team Stony Plain Alto Kevin Solo Calgary Ashkin Allison Solo Edmonton Aslin Lynell Five Person Team Edmonton Atchison Christofer Two Person Team Carstairs Atkins Richard Solo Edmonton Badoni Atul Solo Red Deer Baker Kristin Solo Edmonton Baldigara Michael Solo Kelowna Balla Sarah Five Person Team Edmonton Banmann Aaron Two Person Team Lethbridge Barlow-Bolch Emily Solo Edmonton Barnett Greg Five Person Team Calgary Barrera Miguel Solo Canmore Barrette Joelle Solo Airdrie Bartelds Chad Solo Grande Prairie Bartelds Amanda Solo Grande Prairie Beattie Sean Solo Calgary Begin Jennifer Solo Airdrie Bentley Chris Solo Fernie Bentley Sheri Solo Fernie Bergen Roslyn Solo Edmonton Bergeron Cait Solo Edmonton Berlin Myles Solo Edmonton Bernat Jessica Five Person Team Edmonton Bertrand Richard Solo Fort McMurray Betts Sheldon Solo Cochrane Bidaux Steven Solo Saskatoon Blackburn Craig Solo St Albert Blacquier Donald Solo Lancaster Park Blasius Alex Solo Calgary Bliss Orrie Solo Calgary Boisvenue Melissa Solo Redwood Meadows Borba Renata Two Person Team Edmonton Boyd Suzanne Solo Calgary Brandt Frank Solo Steinbach Brandt Juanita Solo Calgary Bratland Lisa Solo Hythe Bratland Kailey Solo Hythe Brekkas Elana Solo Aurora Brenner Tina Two Person Team Edmonton Brescia Laura Solo Calgary Brezden Julian Solo Edmonton Brinen Peter Solo Red Deer Brochu Rachelle Two Person Team Peace River Brockman Nancy Two -

2018 Municipal Affairs Population List | Cities 1

2018 Municipal Affairs Population List | Cities 1 Alberta Municipal Affairs, Government of Alberta November 2018 2018 Municipal Affairs Population List ISBN 978-1-4601-4254-7 ISSN 2368-7320 Data for this publication are from the 2016 federal census of Canada, or from the 2018 municipal census conducted by municipalities. For more detailed data on the census conducted by Alberta municipalities, please contact the municipalities directly. © Government of Alberta 2018 The publication is released under the Open Government Licence. This publication and previous editions of the Municipal Affairs Population List are available in pdf and excel version at http://www.municipalaffairs.alberta.ca/municipal-population-list and https://open.alberta.ca/publications/2368-7320. Strategic Policy and Planning Branch Alberta Municipal Affairs 17th Floor, Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: (780) 427-2225 Fax: (780) 420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 780-420-1016 Toll-free in Alberta, first dial 310-0000. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2018 Municipal Census Participation List .................................................................................... 5 Municipal Population Summary ................................................................................................... 5 2018 Municipal Affairs Population List ....................................................................................... -

Bylaw 31/2018 Amendment to Waste Management Bylaw Agenda Item: 5C

Town of Cochrane Council Report Meeting: Regular Council Meeting Date: October 9, 2018 Originated By: Fabrizio Bertolo, Manager, Waste & Recycling Title: Bylaw 31/2018 Amendment to Waste Management Bylaw Agenda Item: 5c RECOMMENDED ACTION That Council gives First Reading to Bylaw 31/2018. STRATEGIC / SUSTAINABILITY PLAN ITEM Town of Cochrane Strategic Plan 1.2 Future infrastructure, facilities and plans be developed and implemented to accommodate growth. 1.4 Promote/Advocate the Cochrane Sustainability Plan by aligning our plans and actions. 3.3 Promote and celebrate a culture of engagement, customer service, innovation, responsibility and accountability. Cochrane Sustainability Plan 4. We contribute to the solution on climate change BACKGROUND Attached for First Reading is Bylaw 31/2018 which proposes to amend Town of Cochrane Waste Management Bylaw 08/2018, to reduce residential waste pick up (black carts) from every week to every two weeks. Council adopted the Zero Waste Framework in the Fall of 2012 as the Town of Cochrane’s waste management vision. The Zero Waste Framework outlines how Cochrane can achieve Zero Waste by focusing on reducing our environmental footprint by minimizing the amount of waste that must be landfilled through waste reduction, reuse, recycling, redesign, composting and other actions. The overall vision is Zero Waste with the interim goal of 80% of waste diverted from the landfill by 2020. The Zero Waste Framework identifies 5 Pathways to achieving our goals: Organics (in all sectors), Multi-family Recycling, Industrial Commercial Institutional Recycling, Construction & Demolition Recycling and Events & Public Spaces. Diversion Rate for the Town of Cochrane moved from 31% (2016) to 61% after the implementation of the Organics program. -

2017 Municipal Affairs Population List

2017 Municipal Affairs Population List Population figures are based on the latest municipal or federal census counts reported to the Minister as of September 1, 2017 in compliance with the Determination of Population Regulation 63/2001 under Section 604 of the Municipal Government Act. Strategic Policy and Planning Branch Alberta Municipal Affairs 17th Floor, Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 2017 Municipal Affairs Population List Alberta Municipal Affairs © Government of Alberta 2018 ISSN 978-1-4601-3652-2 ISBN 2368-7320 Printed in Canada The publication is released under the Open Government Licence. This publication and previous editions of the Municipal Affairs Population are available in pdf and excel version at http://www.municipalaffairs.alberta.ca/mc_official_populations and http://open.alberta.ca/publications/2368-7320. Data for this publication are from the 2016 federal census of Canada, or from the 2016 or 2017 municipal census conducted by municipalities. For more detailed data on the census conducted by Alberta municipalities, please contact the municipalities directly. Questions concerning the Municipal Affairs Population List can be directed to: Strategic Policy and Planning Branch Alberta Municipal Affairs 17th Floor, Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: (780) 427-2225 Fax: (780) 420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 780-420-1016 To be connected toll-free in Alberta, first dial 310-0000. - Page ii - 2017 Municipal Affairs Population List Table of Contents Introduction -

2017 Municipal Codes

2017 Municipal Codes Updated December 22, 2017 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] 2017 MUNICIPAL CHANGES STATUS CHANGES: 0315 - The Village of Thorsby became the Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017). NAME CHANGES: 0315- The Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017) from Village of Thorsby. AMALGAMATED: FORMATIONS: DISSOLVED: 0038 –The Village of Botha dissolved and became part of the County of Stettler (effective September 1, 2017). 0352 –The Village of Willingdon dissolved and became part of the County of Two Hills (effective September 1, 2017). CODE NUMBERS RESERVED: 4737 Capital Region Board 0522 Metis Settlements General Council 0524 R.M. of Brittania (Sask.) 0462 Townsite of Redwood Meadows 5284 Calgary Regional Partnership STATUS CODES: 01 Cities (18)* 15 Hamlet & Urban Services Areas (396) 09 Specialized Municipalities (5) 20 Services Commissions (71) 06 Municipal Districts (64) 25 First Nations (52) 02 Towns (108) 26 Indian Reserves (138) 03 Villages (87) 50 Local Government Associations (22) 04 Summer Villages (51) 60 Emergency Districts (12) 07 Improvement Districts (8) 98 Reserved Codes (5) 08 Special Areas (3) 11 Metis Settlements (8) * (Includes Lloydminster) December 22, 2017 Page 1 of 13 CITIES CODE CITIES CODE NO. NO. Airdrie 0003 Brooks 0043 Calgary 0046 Camrose 0048 Chestermere 0356 Cold Lake 0525 Edmonton 0098 Fort Saskatchewan 0117 Grande Prairie 0132 Lacombe 0194 Leduc 0200 Lethbridge 0203 Lloydminster* 0206 Medicine Hat 0217 Red Deer 0262 Spruce Grove 0291 St. Albert 0292 Wetaskiwin 0347 *Alberta only SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE NO. -

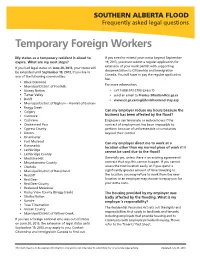

Temporary Foreign Workers

SOUTHERN ALBERTA FLOOD Frequently asked legal questions Temporary Foreign Workers My status as a temporary resident is about to If you need to extend your status beyond September expire. What are my next steps? 19, 2013, you must submit a regular application for extension of your work permit with supporting If you had legal status on June 20, 2013, your status will documentation to Citizenship and Immigration be extended until September 19, 2013, if you live in Canada. You will have to pay the regular application one of the following communities: fee. • Black Diamond For more information: • Municipal District of Foothills • Stoney Nation • call 1-888-242-2100 (press 7) • Turner Valley • send an email to [email protected] • Banff • www.cic.gc.ca/english/visit/extend-stay.asp • Municipal District of Bighorn – Hamlet of Exshaw • Bragg Creek • Calgary Can my employer reduce my hours because the • Canmore business has been affected by the flood? • Cochrane Employers can terminate or reduce hours if the • Crownsnest Pass contract of employment has been impossible to • Cypress County perform because of unforeseeable circumstances • Devon beyond their control. • Drumheller • Fort Macleod Can my employer direct me to work at a • Kananaskis location other than my normal place of work if it • Lethbridge cannot be used due to the flood? • Lethbridge County • Medicine Hat Generally yes, unless there is an existing agreement/ • Mountainview County contract that says this cannot happen. If you cannot • Okotoks access the new location easily or if you spend a • Municipal District of Ranchland significantly greater amount of time traveling to • Redcliff the location, you may refuse to work from the new • Red Deer location or an employer may choose to repay you for • Red Deer County your extra costs. -

Community. Commitment. Results

Community. Commitment. Results. Lilli Young Research [email protected] CALGARY OFFICE Suite 300, 602 12th Avenue SW P: 403-266-1201 ext. 225 Calgary, AB T2R 1J3 F: 403-266-2701 Lilli Young joined Maurice Law as a researcher in September 2013. She holds a Masters of Arts in History (2014) from the University of Lethbridge where she completed her thesis on oral history, memory, and the social and discursive construction of the past. Lilli is currently the Research Director at Maurice Law, and has completed archival research in aboriginal history in numerous government and other institutes across Canada, including the Glenbow Museum, the Provincial Archives of Alberta, and Library and Archives Canada. Lilli has experience collecting, handling, and managing archival documents, and is well practiced in the writing of historical reports and in deducing the historical relevance of primary documents within the current social and legal context. Lilli has held numerous academic research positions as a research assistant in the History, Women’s Studies and Kinesiology departments at the University of Lethbridge. Lilli first gained experience conducting research in aboriginal history when she completed a Education & Professional Memberships project on Southern Alberta residential schools as a volunteer for the Alexander Galt Museum and Archives. Lilli then completed an eight-month co-op work term at the • Canadian Historical Association Litigation Management and Resolution Branch for the Department of Aboriginal Aairs and • Canadian Women Studies Association Northern Development Canada where she gained research experience related to historical Community Engagement & Presentations and current aboriginal litigation issues. Subsequently, she held a position with Smith Research which specialized in land claims and litigation research and support for government departments and First Nations involved in legal actions. -

Great Kids Shine at Annual Awards Ceremony

March 13, 2005 Great Kids shine at annual awards ceremony Edmonton... Nineteen outstanding Alberta children and youth have been honoured for making a difference at home and in their communities. Premier Ralph Klein presented the sixth annual Great Kids Awards during a ceremony at the Fantasyland Hotel in Edmonton on March 13. "I'm overwhelmed at the optimism and the drive these children possess. Their ability to overcome challenges and their compassion for others are inspiring," said Premier Klein. "Each one of these children deserves to be recognized for the difference they have made in the lives of others. They are true role models for us all." Award recipients were selected from among 181 nominations, by a review panel made up of MLAs and community members. In honour of Alberta's Centennial, this year's awards make a total of 100 Great Kids honoured across Alberta. "These Great Kids are truly an inspiration," said Children's Services Minister Heather Forsyth. "They prove that with passion and perseverance, we can all make a positive difference. It's an honour to recognize their outstanding achievements." This year's Great Kids will receive a prize package including an IBM computer, a $500 education bursary from TransCanada, accommodation at the Fantasyland Hotel and gift certificates for West Edmonton Mall. Corporate sponsors of the 2005 Great Kids Award are IBM, TransCanada, West Edmonton Mall and the Fantasyland Hotel. To be eligible for a Great Kids Award, nominees must be residents of Alberta between the ages of five to 18, demonstrate considerable effort in school, contribute to their community through volunteer service and contribute to the quality of home life by willingly assuming responsibilities within their family. -

2019 Municipal Codes

2019 Municipal Codes Updated February 22, 2019 Strategic Policy and Planning 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] 2019 MUNICIPAL CHANGES STATUS / NAME CHANGES: 0019-Effective January 1, 2019, the Town of Beaumont became the City of Beaumont 0111-Effective January 1, 2019, the Municipal District of Foothills No. 31 became Foothills County AMALGAMATED: FORMATIONS: DISSOLVED: 0131-Effective January 1, 2019, the Town of Grande Cache is dissolved and became part of the Municipal District of Greenview No. 16 (0481) CODE NUMBERS RESERVED: 4737 Edmonton Metropolitan Region Board 0524 R.M. of Brittania (Sask.) 0462 Townsite of Redwood Meadows 6586 Calgary Metropolitan Region Board STATUS CODES: 01 Cities (19)* 15 Hamlet & Urban Services Areas (397) 09 Specialized Municipalities (6) 20 Services Commissions (73) 06 Municipal Districts (63) 25 First Nations (52) 02 Towns (107) 26 Indian Reserves (138) 03 Villages (86) 50 Local Government Associations (23) 04 Summer Villages (51) 60 Emergency Districts (12) 07 Improvement Districts (8) 98 Reserved Codes (4) 08 Special Areas (4) 11 Metis Settlements (8) * (Includes Lloydminster) February 22, 2019 Page 1 of 13 CITIES CODE CITIES CODE NO. NO. Airdrie 0003 Beaumont 0019 Brooks 0043 Calgary 0046 Camrose 0048 Chestermere 0356 Cold Lake 0525 Edmonton 0098 Fort Saskatchewan 0117 Grande Prairie 0132 Lacombe 0194 Leduc 0200 Lethbridge 0203 Lloydminster* 0206 Medicine Hat 0217 Red Deer 0262 Spruce Grove 0291 St. Albert 0292 Wetaskiwin 0347 *Alberta only SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE NO. NO. Crowsnest Pass 0361 Jasper 0418 Lac La Biche County 4353 Mackenzie County 0505 Strathcona County 0302 Wood Buffalo 0508 MUNICIPAL DISTRICTS CODE MUNICIPAL DISTRICTS CODE NO. -

Industry Guide 2017-2018

2017-2018 INDUSTRY GUIDE 2017-2018 PROFESSIONAL GOLFERS’ ASSOCIATION OF ALBERTA INDUSTRY GUIDE New: Notes section at the back PGA of Alberta Club Listing Advantage Golf Academy Blackhawk GC Canal at Delacour (The) 97 Cypress Way SE 5111 Range Road 255 Box 20 Medicine Hat, AB T1B 1H1 Spruce Grove, AB T7Y 1A8 Delacour, AB T0M 0T0 T: (403) 504-3272 T: (780) 470-4790 T: (403) 590-4515 F: (403) 529-1010 F: (780) 470-4525 F: (403) 590-4576 Trevor Moore – Teaching Pro Craig McArthur – Head Pro Paul Hemstreet – Head Pro Kevin Chow – Associate Bob Davidchuk – Associate Alberta Springs GR David MacComb – Associate Site 11, Box 7, RR 4 Jacques Plouffe – Associate Canmore G&CC Red Deer, AB T4N 5E4 Evan Dyki – Candidate for Membership 2000-8th Ave T: (403) 342-5995 Canmore, AB T1W 1Y2 F: (403) 342-5995 Blair Oko Golf Academy T: (403) 678-4785 1979 – 111 Street Al Norlin – Head Pro F: (403) 678-6616 Edmonton, AB T6J 7C6 Justin Bennett – Associate Darren Cooke – Executive Pro T: (780) 496-9534 Luke Rundell – Associate Richard Eichele – Head Pro F: (780) 432-1627 Blair Oko – Head Teaching Pro Dana Down – Associate Apple Creek GC Bill Dreger – Associate 11064 TWP Road 275 Chris Cooke – Candidate for Membership Rockyview, AB T4B 2A3 Blue Devil GC 2300 – 194 Ave SE T: (403) 912-2191 Canyon Meadows G&CC Tyler Babkirk – Head Pro Calgary, AB T2X 0R3 12501-14th Street SW Edmund Dzieciuch – Candidate for Membership T: (403) 452-7892 F: (403) 452-8691 Calgary, AB T2W 2Y8 Ardmore GC Blake Clayton – Head Pro T: (403) 281-1188 F: (403) 251-6620 5105 50th Street Doug