Report, Situation in the Central African Republic II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central African Republic Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #4 01-21

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #4, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2014 JANUARY 21, 2014 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA 1 F U N D I N G HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2014 Conditions in the Central African Republic (CAR) remain unstable, and insecurity continues to constrain 2.6 19% 19% humanitarian efforts across the country. million The U.S. Government (USG) provides an additional $30 million in humanitarian Estimated Number of assistance to CAR, augmenting the $15 People in CAR Requiring 12% million contributed in mid-December. Humanitarian Assistance U.N. Office for the Coordination of 26% HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) – December 2013 TO CAR IN FY 2014 24% USAID/OFDA $8,008,810 USAID/FFP2 $20,000,000 1.3 Health (19%) State/PRM3 $17,000,000 million Humanitarian Coordination & Information Management (26%) Estimated Number of Logistics & Relief Commodities (24%) $45,008,810 Food-Insecure People Protection (12%) TOTAL USAID AND STATE in CAR ASSISTANCE TO CAR U.N. World Food Program (WFP) – Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (19%) December 2013 KEY DEVELOPMENTS 902,000 Since early December, the situation in CAR has remained volatile, following a pattern of Total Internally Displaced rapidly alternating periods of calm and spikes in violence. The fluctuations in security Persons (IDPs) in CAR conditions continue to impede humanitarian access and aid deliveries throughout the OCHA – January 2014 country, particularly in the national capital of Bangui, as well as in northwestern CAR. Thousands of nationals from neighboring African countries have been departing CAR 478,383 since late December, increasing the need for emergency assistance within the region as Total IDPs in Bangui countries strive to cope with returning migrants. -

OCHA CAR Snapshot Incident

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Overview of incidents affecting humanitarian workers January - May 2021 CONTEXT Incidents from The Central African Republic is one of the most dangerous places for humanitarian personnel with 229 1 January to 31 May 2021 incidents affecting humanitarian workers in the first five months of 2021 compared to 154 during the same period in 2020. The civilian population bears the brunt of the prolonged tensions and increased armed violence in several parts of the country. 229 BiBiraorao 124 As for the month of May 2021, the number of incidents affecting humanitarian workers has decreased (27 incidents against 34 in April and 53 in March). However, high levels of insecurity continue to hinder NdéléNdélé humanitarian access in several prefectures such as Nana-Mambéré, Ouham-Pendé, Basse-Kotto and 13 Ouaka. The prefectures of Haute-Kotto (6 incidents), Bangui (4 incidents), and Mbomou (4 incidents) Markounda Kabo Bamingui were the most affected this month. Bamingui 31 5 Kaga-Kaga- 2 Batangafo Bandoro 3 Paoua Batangafo Bandoro Theft, robbery, looting, threats, and assaults accounted for almost 60% of the incidents (16 out of 27), 2 7 1 8 1 2950 BriaBria Bocaranga 5Mbrès Djéma while the 40% were interferences and restrictions. Two humanitarian vehicles were stolen in May in 3 Bakala Ippy 38 2 Bossangoa Bouca 13 Bozoum Bouca Ippy 3 Bozoum Dekoa 1 1 Ndélé and Bangui, while four health structures were targeted for looting or theft. 1 31 2 BabouaBouarBouar 2 4 1 Bossangoa11 2 42 Sibut Grimari Bambari 2 BakoumaBakouma Bambouti -

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

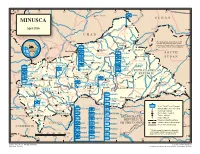

MINUSCA T a Ou M L B U a a O L H R a R S H Birao E a L April 2016 R B Al Fifi 'A 10 H R 10 ° a a ° B B C H a VAKAGA R I CHAD

14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° ZAMBIA Am Timan é Aoukal SUDAN MINUSCA t a ou m l B u a a O l h a r r S h Birao e a l April 2016 r B Al Fifi 'A 10 h r 10 ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh Garba The boundaries and names shown ouk ahr A Ouanda and the designations used on this B Djallé map do not imply official endorsement Doba HQ Sector Center or acceptance by the United Nations. CENTRAL AFRICAN Sam Ouandja Ndélé K REPUBLIC Maïkouma PAKISTAN o t t SOUTH BAMINGUI HQ Sector East o BANGORAN 8 BANGLADESH Kaouadja 8° ° SUDAN Goré i MOROCCO u a g n i n i Kabo n BANGLADESH i V i u HAUTE-KOTTO b b g BENIN i Markounda i Bamingui n r r i Sector G Batangafo G PAKISTAN m Paoua a CAMBODIA HQ Sector West B EAST CAMEROON Kaga Bandoro Yangalia RWANDA CENTRAL AFRICAN BANGLADESH m a NANA Mbrès h OUAKA REPUBLIC OUHAM u GRÉBIZI HAUT- O ka Bria Yalinga Bossangoa o NIGER -PENDÉ a k MBOMOU Bouca u n Dékoa MAURITANIA i O h Bozoum C FPU CAMEROON 1 OUHAM Ippy i 6 BURUNDI Sector r Djéma 6 ° a ° Bambari b ra Bouar CENTER M Ouar Baoro Sector Sibut Baboua Grimari Bakouma NANA-MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO- BASSE MBOMOU M WEST Obo a Yaloke KOTTO m Bossembélé GRIBINGUI M b angúi bo er ub FPU BURUNDI 1 mo e OMBELLA-MPOKOYaloke Zémio u O Rafaï Boali Kouango Carnot L Bangassou o FPU BURUNDI 2 MAMBÉRÉ b a y -KADEI CONGO e Bangui Boda FPU CAMEROON 2 Berberati Ouango JTB Joint Task Force Bangui LOBAYE i Gamboula FORCE HQ FPU CONGO Miltary Observer Position 4 Kade HQ EGYPT 4° ° Mbaïki Uele National Capital SANGHA Bondo Mongoumba JTB INDONESIA FPU MAURITANIA Préfecture Capital Yokadouma Tomori Nola Town, Village DEMOCRATICDEMOCRATIC Major Airport MBAÉRÉ UNPOL PAKISTAN PSU RWANDA REPUBLICREPUBLIC International Boundary Salo i Titule g Undetermined Boundary* CONGO n EGYPT PERU OFOF THE THE CONGO CONGO a FPU RWANDA 1 a Préfecture Boundary h b g CAMEROON U Buta n GABON SENEGAL a gala FPU RWANDA 2 S n o M * Final boundary between the Republic RWANDA SERBIA Bumba of the Sudan and the Republic of South 0 50 100 150 200 250 km FPU SENEGAL Sudan has not yet been determined. -

République Centrafricaine - Préfecture : Kémo Date De Production :Février 2015

Pour Usage Humanitaire Uniquement République Centrafricaine - Préfecture : Kémo Date de production :février 2015 Bazoyua Mbrés Bongo Mbrès Tao Wangué 1 Bobani Karagoua Bonou 2 Lady Lakouéténé Zimi-Gbagoua Zamboutou Gbawi Bokoga Yangoumara Gbada-Wangue Ndjangala Ouham Botto Fafa Gokara Boua Bambia 1 Mbiti Mbrès Badolé Bambia 2 Ndenga Kanda Nana-Gribizi Mbrés Sabayanga 2 Boboin Sabayanga Kaga-Bandoro Scieurs Bogoué Boya Gribizi 1 Bokolo Bogoué Bokago Somboké Morobanda 1 Yandoba Morobanda 2 Bokaga Beya Mbambi Bouca Bayolo Gboréa Bérabofidoua Banou Togbo Bac Bongoyo 1 Koumi Mboussa Mbouilli Mbolokpaka Baguiti 2 Begbayolo Bouloua Béboguila Koua Dissikou 4 Dissikou 3 Wapo Banda-Mandja 2 Dissikou Bofoulou Béra-Bobo Bokada Baguiti 1 Ba-Bobo Orongou 2 Orongou 1 Dekoa Bozagba Bouca Bofere Wandalongo Bobo Mbou Gou 2 Gou 1 Bombaroua Gbegon Begueze Yaligaza Daya Kagaya Bégou Bofidoua 2 Bafada Boanga Yangassa Bandagoli Baguela Kobadja Baïdou-Ngoumbourou Sidi-Ndolo Bakala Banda-Mandja 1 Lah Dekoa Saboyombo Ouolo 1 Plémandji Bengbali Begbaranga Malékara Ippy Oualo Ngbéré Tilo Koudou-Bégo Gpt Bobatoua 2 Niamou Tilo Binguifara Bedonga Gpt Donzi Yombandji Bekofe 1 Gazaporo Bekofe 2 Ngoro Bédambou Zourou Bovoula Baguiti 2 Mbimbi Fôh Cotonaf Tilo Simandele Tilo Madomalé Pélékesse Guiffa Ndéré Bodo Bongo 2 Bokoro Zouhouli Bongo Danga-Gboudou Dékoa Badéré Poukouya Bambari Sabone Koudoukou Oualambélé Mourouba Ngarambéti Mbimé-Yomba Bodengue Mbadjié Dobalé Ndakadja Ouham Bouca Mala Yonga Mabanga Bakabi Katakpa Mala Ndamiri Yomba Bakala Binguimalé Piangou Oumari -

Lake Chad Basin

Integrated and Sustainable Management of Shared Aquifer Systems and Basins of the Sahel Region RAF/7/011 LAKE CHAD BASIN 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION EDITORIAL NOTE This is not an official publication of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The content has not undergone an official review by the IAEA. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the IAEA or its Member States. The use of particular designations of countries or territories does not imply any judgement by the IAEA as to the legal status of such countries or territories, or their authorities and institutions, or of the delimitation of their boundaries. The mention of names of specific companies or products (whether or not indicated as registered) does not imply any intention to infringe proprietary rights, nor should it be construed as an endorsement or recommendation on the part of the IAEA. INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION REPORT OF THE IAEA-SUPPORTED REGIONAL TECHNICAL COOPERATION PROJECT RAF/7/011 LAKE CHAD BASIN COUNTERPARTS: Mr Annadif Mahamat Ali ABDELKARIM (Chad) Mr Mahamat Salah HACHIM (Chad) Ms Beatrice KETCHEMEN TANDIA (Cameroon) Mr Wilson Yetoh FANTONG (Cameroon) Mr Sanoussi RABE (Niger) Mr Ismaghil BOBADJI (Niger) Mr Christopher Madubuko MADUABUCHI (Nigeria) Mr Albert Adedeji ADEGBOYEGA (Nigeria) Mr Eric FOTO (Central African Republic) Mr Backo SALE (Central African Republic) EXPERT: Mr Frédèric HUNEAU (France) Reproduced by the IAEA Vienna, Austria, 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION Table of Contents 1. -

OCHA CAR Snapshot Incident

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Overview of incidents affecting humanitarian workers January 2021 CONTEXT Incidents from The civilian population remains the first victim of the renewed tensions 1 January to 31 January 2021 and violence observed in the country since the end of 2020. The significant increase in incidents affecting humanitarian aid workers 66 Birao in January reflects the acute insecurity in several prefectures where 12 armed confrontations took place, such as Lobaye, Ombella Mpoko and Mbomou. Ndélé In January, nearly 90% of the 66 incidents recorded (the highest monthly 5 Markounda figure since 2017) involved robberies, burglaries, and looting. Armed Kabo Bamingui confrontations were not the direct cause of incidents, but the absence of 31 2 Kaga-Kaga- 1 Batangafo Bandoro Batangafo Bandoro security forces in several cities encouraged opportunistic criminal acts. 2 1 1 508 BriaBria 5 Djéma During the month, 4 humanitarian vehicles were stolen, 2 of them were 3 Bakala Ippy 38 Bouca 5 BBozoumozoum Bouca 1 3 recovered. Bossangoa 2 Dekoa 1 BabouaBouar 1 4 Bouar 611 Rafai 2 Bossangoa Sibut Grimari Bambari 22 2 Bambari Bakouma INCIDENTS DEATH INJURED Bogangolo 32 Zémio Obo 8 5 1 Bangassou 7 Damara Kouango 14 Carnot Boali 7 12 1 1 Gambo 2 1 Bimbo 2 61,4% 1 Bangassou 66 0 0 Boda Mbaiki Jan 2021 2 Jan 2021 1 Mongoumba X # D’INCIDENTS Satema 0 1 - 2 Bangui PERCENTAGE OF INCIDENTS BY TYPE NUMBER OF INCIDENTS Bangui 3- 4 3 5 - 9 Intimidation Bangassou 14 10 - 14 Threats => 15 Agression (6) Bambari 8 7.6% Kaga-Bandoro 8 Interferences 20,8% Bossangoa INCIDENTS TRENDS OVER THE PAST 12 MONTHS /restrictions (8) 23.9%24.4% 6 23.9%24.4%12.1% Burglary N'dele 5 49,8%40.746%37% Robbery 66 40.737% intrusion Bria 5 59 80.3% (53) 66 Bangui 3 27,8% 40 38 38 37 37 39 30.2% Kabo 2 35 33 34.8%30.2% 27 26 34.8% Boda 2 19 Bouca 2 2021 Top 10 sub-prefectures affected Jan Feb Mars Apr May June July Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan The boundaries, names shown, and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Central African Republic Cash Based Initiatives (1 Jan - 30 June 2020)

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC CASH BASED INITIATIVES (1 JAN - 30 JUNE 2020) KEY FIGURES Resilience KEY FIGURES Voucher 201K $1.2M people Electronic Emergency Transfer Response Development Cash 1.7K $4.8M Transfer people Non Emergency $1M Emergency 9.4K Response 60K $6.2M $5.2M Response 263K people people assisted with cash provided to affected people assisted provided to affected transfers by World Bank’s initiative people people $187K CASH BENEFICIARIES BY SUB PREFECTURE IMPLEMENTATION TYPE OF CBI REACHED BY CLUSTER LOCATIONS ORGANISATIONS 3,268 3,200 2,893 NNGO 10 Food Security Nutrition LCS* Shelter/NFI/CCCM Protection 195K 16K 37K 13K 1.7K 23 people people people people Partners INGO 9 people Kaga-Bandoro Berbérati Bangassou Sub Prefectures $4.6M $0.32M $1.1M $0.15M $0.08M TOP TEN Donor funding Cash Assistance 24 out of 71 UN IN MILLIONS (USD) 4 *Livelihood and community stabilization USAID 4.06 1.5 CASH BENEFICIARIES BY SUB PREFECTURE 2.28 Humanitarian Response Multidonors 72,156 30,994 29,654 24,122 14,492 14,100 7,479 7,124 6,697 6,380 EU 0.7 Kaga-Bandoro Ngaoundaye Paoua Bambari Bria Bouar Bozoum Bangui Dékoa Bossangoa GFFO 0.6 The remaining 49,412 beneficiaries are located in 14 other Sub Prefectures. FRANCE 0.18 KEY FIGURES CASH BENEFICIARIES BY SUB PREFECTURE Cash SIDA 0.16 Transfer 44K Netherlands 0.11 people 39,546 26,139 8,479 6,442 6,362 UNICEF 0.09 Electronic Transfer COVID 19 Bambari Ippy Bakala Bangui Grimari KLINSKY 0.06 99K 55K $2.3M people assisted people provided to affected The remaining 11,654 beneficiaries are located in 10 Others 0.23 people other Sub Prefectures. -

A Study of the Primary Granitoid Outcroppings and Sedimentary Rocks in the Boali Region of the Central African Republic

7 A Study of the Primary Granitoid Outcroppings and Sedimentary Rocks in the Boali Region of the Central African Republic Narcisse Bassanganam, Yang Mei Zhen, Prince E. Yedidya Danguene, Minfang Wang Earth Resource, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China Earth Faculty, University of Bangui, Central African Republic Abstract Located in the Central African Republic, the region of Boali is noted for its waterfalls and for the nearby hydroelectric projects. The waterfalls of Boali are 250 m wide and 50 m high, and are a popular tourist destination. The Central African Republic (CAR) has large reserves of Granitoids that remain largely untapped. That is why these rocks, which outcrop and which constitute the base of the Boali region and its surroundings, caught our attention. Previous studies by Bowen (1915) explained the order of appearance of various minerals as a function of the temperature and initial magma (SiO2) content. According to Bowen’s diagram, we can say that the magma underwent a magmatic differentiation giving rocks that are poor in silica (Diorite), followed by rocks rich in silica (Granodiorite and Granite). Knowing the absolute age of the Granitoids on the edge of the craton of Mbomou (2.1 Ga, Moloto et al., 2008, and Toteu et al, 1994), we can deduce the chronology of other formations. Initially there was the formation of the metamorphic formations and sandstones of Boali. This was followed by a slow intrusion of magma which crystallized in depth to give grainy rock (granitoids and pegmatite) in the region of Boali. This intrusion had metamorphosed the pre- existing formations through an orthogneiss. -

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC RIGHTS Materials Published by Human Rights Watch WATCH Since the March 2013 Seleka Coup

HUMAN CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC RIGHTS Materials Published by Human Rights Watch WATCH since the March 2013 Seleka Coup Central African Republic Materials Published by Human Rights Watch since the March 2013 Seleka Coup Copyright © 2014 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org Central African Republic Materials Published Since the Seleka Coup This document contains much of Human Rights Watch’s reporting on the human rights situation in the Central African Republic following the March 24, 2013 coup d’état against former President François Bozizé. For all of Human Rights Watch’s work on Central African Republic, including photographs, satellite imagery, and reports, please visit our website: https://www.hrw.org/africa/central-african-republic. -

République Centrafricaine

République Centrafricaine Pour usage Déplacement de population dans les régions humanitaire uniquement du Nord-Est - Situation au mois de janvier 2012 Nombre de déplacés par Sous-Préfecture Pas de données 0 - 1000 $ 1000 - 2500 Birao 2500 - 7500 Chad EEE1429 7500 - 15000 Vakaga 15000 - 25000 Nombre de EEE 500 Ouanda-Djallé déplacés estimé EEE225 Ndélé !! Camp de déplacés EEE6516 Sudan Bamingui-Bangoran Fertit Bamingui Ouadda Kabo EEE812 Markounda !! Centr al Haute-Kotto Afr ican Nangha Batangafo Repub lic Boguila Kaga-Bandoro Yalinga Nana-Bakassa Yadé Mbrès Ouham Nana-Gribizi Bria EEE5208 Bakala Ippy Djéma Bouca Dékoa Ouaka Mala Haut-Mbomou Bossangoa Kémo Kagas Sibut Rafai Haut-Oubangui Grimari Bambari!! Bakouma Mbomou Bogangolo Congo, Alindao Zémio Obo Bambouti Bossembélé Plateaux Ndjoukou Bangassou DRC Yaloké Kouango Mingala !!!! !! Boali Damara !!!! Nombre de retournés par Sous-Préfecture Pas de données 0 - 5000 5000 - 10000 10000 - 13000 Birao Chad Nombre de retournés estimé EEE5652 EEE 500 (revenant d'un déplacement au sein Vakaga de la RCA ou dans les pays voisins) !! Camp de déplacés Ouanda Sudan Djallé Ndélé EEE6880 Bamingui-Bangoran Fertit Ouadda Bamingui Kabo !! Markounda Haute-Kotto Centr al Afr ican Nangha Batangafo Repub lic Yalinga Boguila Ouham Kaga-Bandoro Nana-Bakassa Mbrès Yadé Nana-Gribizi Bria Bossangoa EEE8736 Bakala Ippy Djéma Bossangoa Bouca Kagas Dékoa Ouaka Mala Haut-Mbomou Kémo Rafai Bogangolo Sibut Bambari Haut-Oubangui Grimari !! Bakouma Mbomou Ombella Basse-Kotto Congo, Yaloké M'Poko Ndjoukou Alindao Bangassou -

Failing to Prevent Atrocities in the Central African Republic

Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect Occasional Paper Series No. 7, September 2015 Too little, too late: Failing to prevent atrocities in the Central African Republic Evan Cinq-Mars The Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect was established in February 2008 as a catalyst to promote and apply the norm of the “Responsibility to Protect” populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. Through its programs and publications, the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect is a resource for governments, international institutions and civil society on prevention and early action to halt mass atrocity crimes. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Occasional Paper was produced with the generous support of Humanity United. ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Evan Cinq-Mars is an Advocacy Officer at the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, where he monitors populations at risk of mass atrocities in Central African Republic (CAR), Burundi, Guinea and Mali. Evan also coordinates the Global Centre’s media strategy. Evan has undertaken two research missions to CAR since March 2014 to assess efforts to uphold the Responsibility to Protect (R2P). He has appeared as an expert commentator on the CAR situation on Al Jazeera and the BBC, and his analysis has appeared in Bloomberg, Foreign Policy, The Globe and Mail, Radio France International, TIME and VICE News. Evan was previously employed by the Centre for International Governance Innovation. He holds an M.A. in Global Governance, specializing in Conflict and Security, from the Balsillie School of International Affairs at the University of Waterloo. COVER PHOTO: Following a militia attack on a Fulani Muslim village, wounded children are watched over by Central African Republic soldiers in Bangui.