A Context for Eminem's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

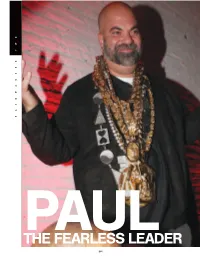

The Fearless Leader Fearless the Paul 196

TWO RAINMAKERS PAUL THE FEARLESS LEADER 196 ven back then, I was taking on far too many jobs,” Def Jam Chairman Paul Rosenberg recalls of his early career. As the longtime man- Eager of Eminem, Rosenberg has been a substantial player in the unfolding of the ‘‘ modern era and the dominance of hip-hop in the last two decades. His work in that capacity naturally positioned him to seize the reins at the major label that brought rap to the mainstream. Before he began managing the best- selling rapper of all time, Rosenberg was an attorney, hustling in Detroit and New York but always intimately connected with the Detroit rap scene. Later on, he was a boutique-label owner, film producer and, finally, major-label boss. The success he’s had thus far required savvy and finesse, no question. But it’s been Rosenberg’s fearlessness and commitment to breaking barriers that have secured him this high perch. (And given his imposing height, Rosenberg’s perch is higher than average.) “PAUL HAS Legendary exec and Interscope co-found- er Jimmy Iovine summed up Rosenberg’s INCREDIBLE unique qualifications while simultaneously INSTINCTS assessing the State of the Biz: “Bringing AND A REAL Paul in as an entrepreneur is a good idea, COMMITMENT and they should bring in more—because TO ARTISTRY. in order to get the record business really HE’S SEEN healthy, it’s going to take risks and it’s going to take thinking outside of the box,” he FIRSTHAND told us. “At its height, the business was run THE UNBELIEV- primarily by entrepreneurs who either sold ABLE RESULTS their businesses or stayed—Ahmet Ertegun, THAT COME David Geffen, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert FROM ALLOW- were all entrepreneurs.” ING ARTISTS He grew up in the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, surrounded on all sides TO BE THEM- by music and the arts. -

Eminem Interview Download

Eminem interview download LINK TO DOWNLOAD UPDATE 9/14 - PART 4 OUT NOW. Eminem sat down with Sway for an exclusive interview for his tenth studio album, Kamikaze. Stream/download Kamikaze HERE.. Part 4. Download eminem-interview mp3 – Lost In London (Hosted By DJ Exclusive) of Eminem - renuzap.podarokideal.ru Eminem X-Posed: The Interview Song Download- Listen Eminem X-Posed: The Interview MP3 song online free. Play Eminem X-Posed: The Interview album song MP3 by Eminem and download Eminem X-Posed: The Interview song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru 19 rows · Eminem Interview Title: date: source: Eminem, Back Issues (Cover Story) Interview: . 09/05/ · Lil Wayne has officially launched his own radio show on Apple’s Beats 1 channel. On Friday’s (May 8) episode of Young Money Radio, Tunechi and Eminem Author: VIBE Staff. 07/12/ · EMINEM: It was about having the right to stand up to oppression. I mean, that’s exactly what the people in the military and the people who have given their lives for this country have fought for—for everybody to have a voice and to protest injustices and speak out against shit that’s wrong. Eminem interview with BBC Radio 1 () Eminem interview with MTV () NY Rock interview with Eminem - "It's lonely at the top" () Spin Magazine interview with Eminem - "Chocolate on the inside" () Brian McCollum interview with Eminem - "Fame leaves sour aftertaste" () Eminem Interview with Music - "Oh Yes, It's Shady's Night. Eminem will host a three-hour-long special, “Music To Be Quarantined By”, Apr 28th Eminem StockX Collab To Benefit COVID Solidarity Response Fund. -

The 2014 Sony Hack and the Role of International Law

The 2014 Sony Hack and the Role of International Law Clare Sullivan* INTRODUCTION 2014 has been dubbed “the year of the hack” because of the number of hacks reported by the U.S. federal government and major U.S. corporations in busi- nesses ranging from retail to banking and communications. According to one report there were 1,541 incidents resulting in the breach of 1,023,108,267 records, a 78 percent increase in the number of personal data records compro- mised compared to 2013.1 However, the 2014 hack of Sony Pictures Entertain- ment Inc. (Sony) was unique in nature and in the way it was orchestrated and its effects. Based in Culver City, California, Sony is the movie making and entertain- ment unit of Sony Corporation of America,2 the U.S. arm of Japanese electron- ics company Sony Corporation.3 The hack, discovered in November 2014, did not follow the usual pattern of hackers attempting illicit activities against a business. It did not specifically target credit card and banking information, nor did the hackers appear to have the usual motive of personal financial gain. The nature of the wrong and the harm inflicted was more wide ranging and their motivation was apparently ideological. Identifying the source and nature of the wrong and harm is crucial for the allocation of legal consequences. Analysis of the wrong and the harm show that the 2014 Sony hack4 was more than a breach of privacy and a criminal act. If, as the United States maintains, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (herein- after North Korea) was behind the Sony hack, the incident is governed by international law. -

Cnn's Tony Harris Interviews Students

SINCE 1947 An upbeat paper http://srt5.atlantapublicschools. forLACROSS a downtown school us/grady/ BAND ECONOMY THEN AND NOW Freshman group Fire stations closed, Is surge in student rocks music scene personnel laid off in activism a modern-day on campus city’s budget cuts civil rights movement? p. 12 p. 10 pp. S1-S4 HENRY W. GRADY HIGH SCHOOL, ATLANTA VOLUME LXII, NUMBER 5, Feb. 2, 2009 CNN’S TONY HARRIS INTERVIEWS STUDENTS BY Emm A FR E NCH reasons we wanted to talk to young people was be- studio to film a live interview on Jan. 9. group of students spoke their minds last Decem- cause at that time President-elect Obama’s campaign According to Chillag, Grady students were ber, when CNN reporter Tony Harris visited was very much helped by organized young people who chosen to participate because “the school A the school to interview them in what became a were very excited about the election,” CNN writer and is a historic place in Atlanta and has series of broadcasts titled “Class in Session.” In the in- segment producer Amy Chillag said. “We thought that the diversity [we wanted].” terview the it would make sense, once he was in office, to interview 13 stu- high school kids and talk about what made them so see CNN page 6 d e n t s excited about him and what issues he needs to tackle voiced and prioritize.” t h e i r Four students—seniors Taylor Fulton and Mike thoughts on Robinson, junior Caroline McKay and sophomore the economy, Michael Barlow— made such an impression in the education, race, interview segments that CNN invited them to the the war in Iraq and President Obama’s new administration. -

Body in the Lyrics of Tori Amos

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 3-2014 "Purple People": "Sexed" Linguistics, Pleasure, and the "Feminine" Body in the Lyrics of Tori Amos Megim A. Parks California State University - San Bernardino Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Parks, Megim A., ""Purple People": "Sexed" Linguistics, Pleasure, and the "Feminine" Body in the Lyrics of Tori Amos" (2014). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 5. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/5 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “PURPLE PEOPLE”: “SEXED” LINGUISTICS, PLEASURE, AND THE “FEMININE” BODY IN THE LYRICS OF TORI AMOS ______________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino ______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition ______________________ by Megim Alexi Parks March 2014 “PURPLE PEOPLE”: “SEXED” LINGUISTICS, PLEASURE, AND THE “FEMININE” BODY IN THE LYRICS OF TORI AMOS ______________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino ______________________ by Megim Alexi Parks March 2014 ______________________ Approved by: Dr. Jacqueline Rhodes, Committee Chair, English Dr. Caroline Vickers, Committee Member Dr. Mary Boland, Graduate Coordinator © 2014 Megim Alexi Parks ABSTRACT The notion of a “feminine” style has been staunchly resisted by third-wave feminists who argue that to posit a “feminine” style is essentialist. -

PDF (1.01 Mib)

.Two long-awaitetj albums from Lilith f aves MATTHEW CARDINALE contributing writer The latest from Tori Amos and Paula Cole are journeys: Tori's journey deep- er into planet electronica and Paula's al growth in "Pearl," kindness in affirmation of love and divinity. "Amen" and love in "God is Watch- Together, they're just perfect to take ing Us." us into the new millennium. Paula's music has become fuller, more I'm not sure if To Venus and Back When consistent and more complete. Sure, can You're is the correct title for Tori's new desig a rock she's not doing the verse/ chorus repeat n Your o,,, star like li . P1tli "fl double-disc album, because I don't vvn Ug/ on Arn Oro thing anymore, but who is these days think she's really come back at ry Shirts os, You besides Ricky Martin. "I Wanna be Some- 0 . too. all. Disc one is a forest of brand l'v7. n her third body" features T-Boz from TLC, just new material, while disc two is Sh:rylanc1, p 。 オ セ 。 ケ lost in th Flt gets pretty, one example of Paula's objective to inte- Tori live in concert during her Lilith セ 。 ウ later rea Cofe sto'P e Woods Of liI>lforo the rhymes are work- grate Lilith Fair pop with R&B. She . th air st. I scued b 'Ped t d e hetic a Warts .S: a er. 0 take a ing and it's lovely. The last track, sounds a bit like Mary Blige as she , recent Plugge tour: our own pn- 0 ry J. -

ARIA Charts, 1996-04-21 to 1996-06-02

Enjoy CifqrZ ria a TRADE MARK REGD CHART AUS TR A LIAN SINGLES CHA VMS CHART TW LW TI TITLE / ARTIST 1W LW TI TITLE / ARTIST 1 1 8 HOW BIZARRE O.M.C. HUH/POL 5776202 1 1 35 JAGGED LITTLE PILL Alanis Morissette A3 WEA/WAR 9362459012 2 2 10 MISSING THE REMIX EP Everything But The Girl • WEA/WAR 2 3 27 (WHAT'S THE STORY) MORNING GLORY Oasis A4 CRE/SONY 481020.2 3 4 8 FATHER & SON Boyzone PDR/POL 5776792 3 2 5 FALLING INTO YOU Celine Dion A EPI/SONY 483792.2 4 3 12 ONE OF US Joan Osborne A MER/POL 8523682 4 6 16 PRESIDENTS OF THE U.S.A. Presidents Of The U.S.A. A COL/SONY 481039.2 5 6 3 CALIFORNIA LOVE 2Pac ISUPOL 8545692 5 4 21 THE MEMORY OF TREES Enya A3 WEA/WAR 0630128792 6 7 9 ANYTHING 3T EPI/SONY 662696.2 6 8 9 TENNESSEE MOON Neil Diamond A COUSONY 481378.2 7 5 9 SPACEMAN Babylon Zoo • EMI 8826492 7 7 20 NEW BEGINNING Tracy Chapman A WEA/WAR 7559618502 8 10 5 IRONIC Alanis Morissette WEA/WAR 93624365 8 9 25 MELLON COLLIE &THE INFINITE SADNESS Smashing Pumpkins A VIR/EMI 8408642 9 8 12 POWER OFA WOMAN Eternal EMI 8825142 9 5 3 TINY MUSIC... FROM THE VATICAN GIFT SHOP Stone Temple Pilots EW/WAR 7567828712 * 10 NEW SALVATION The Cranberries ISUPOL 8546172 10 11 2 GREATES ITS VOLUME 1 Take That BMG 4321355582 11 9 9 GET DOWN ON IT Peter Andre (Feat. -

Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep March 2003 3-28-2003 Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_mar Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003" (2003). March. 14. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_mar/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2003 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in March by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Thll the troth March28,2003 + FRIDAY and don't be afraid. • VO LUME 87 . NUMBER 123 THE DA ILYEASTERN NEWS . COM THE DAILY Four for 400 Eastern baseball team has four chances this weekend to earn head coach Jim EASTERN NEWS <:rlh....,,t n his 400th career Student fees may be hiked • Fees may raise $70 next semester By Avian Carrasquillo STUDENT GOVERNMENT ED ITOR If approved students can expect to pay an extra $70.55 in fees per semester. The Student Senate Thition and Fee Review Committee met Thursday to make its final vote on student fees for next year. Following the committee's approval, the fee proposals must be approved by the Student Senate, vice president for student affairs, the President's Council and Eastern's Board of Trustees. The largest increase of the fees will come in the network fee, which will increase to $48 per semester to fund a 10-year network improvement project. The project, which could break ground as early as this summer would upgrade the campus infra structure for network upgrades, which will Tom Akers, head coach of Eastern's track and field team, watches high jumpers during practice Thursday afternoon. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

Customer Service Policies

Dear Concessionaire: From the entire Concessions & Quality Assurance staff, welcome to Detroit Metropolitan Airport. We hope to make your experience at Detroit Metro exciting, enjoyable, and profitable. The Concessions Department is comprised of professionals with experience in airport planning, real estate management and development, retail/food and beverage management, marketing, contracting, and finance. Our main goal is to ensure your initial and continued success at the Airport. Many of the passengers who arrive at Detroit Metro Airport are here for the first time. First impressions are important. We want to strive to make the Airport an enjoyable environment for all travelers. Our day-to-day concessions management will focus on the following areas: customer service, contract administration and compliance, performance standards monitoring, marketing and promotion, contract support, and tenant coordination support. Attached is the Tenant Handbook, which details useful reference information and various policies and procedures. Please make this important reference available to your on-site staff. Our doors are open to you at any time. We enjoy exploring any ideas you have to improve the concession program and your own business. We are available to assist with any emergencies that may arise. Your success is our mission. Sincerely, Greg Hatcher Director of Concessions & Quality Assurance 1 Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport Table of Contents- North Terminal 1.0 Reference Information 1.1 Concessions and Quality Assurance Department -

Marketing Violent Entertainment to Children Report

MARKETING VIOLENT ENTERTAINMENT TO CHILDREN: A REVIEW OF SELF-REGULATION AND INDUSTRY PRACTICES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, MUSIC RECORDING & ELECTRONIC GAME INDUSTRIES REPORT OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION SEPTEMBER 2000 Federal Trade Commission Robert Pitofsky, Chairman Sheila F. Anthony Commissioner Mozelle W. Thompson Commissioner Orson Swindle Commissioner Thomas B. Leary Commissioner TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................1 A. President’s June 1, 1999 Request for a Study and the FTC’s Response ........................................................1 B. Public Concerns About Entertainment Media Violence ...................1 C. Overview of the Commission’s Study ..................................2 Focus on Self-Regulation ...........................................2 Structure of the Report .............................................3 Sources .........................................................4 II. THE MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY SELF-REGULATORY SYSTEM .......4 A. Scope of Commission’s Review ......................................5 B. Operation of the Motion Picture Self-Regulatory System .................6 1. The rating process ..........................................6 2. Review of advertising for content and rating information .........8 C. Issues Not Addressed by the Motion Picture Self-Regulatory System .......10 1. Accessibility of reasons for ratings ............................10 2. Advertising placement -

Defining Music As an Emotional Catalyst Through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2011 All I Am: Defining Music as an Emotional Catalyst through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture Adrienne M. Trier-Bieniek Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Therapy Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Trier-Bieniek, Adrienne M., "All I Am: Defining Music as an Emotional Catalyst through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture" (2011). Dissertations. 328. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/328 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "ALL I AM": DEFINING MUSIC AS AN EMOTIONAL CATALYST THROUGH A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF EMOTIONS, GENDER AND CULTURE. by Adrienne M. Trier-Bieniek A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology Advisor: Angela M. Moe, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2011 "ALL I AM": DEFINING MUSIC AS AN EMOTIONAL CATALYST THROUGH A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF EMOTIONS, GENDER AND CULTURE Adrienne M. Trier-Bieniek, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2011 This dissertation, '"All I Am': Defining Music as an Emotional Catalyst through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture", is based in the sociology of emotions, gender and culture and guided by symbolic interactionist and feminist standpoint theory.