Arizona's Changing Rivers: How People Have Affected the Rivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologic Map of the Chino Valley North 7½' Quadrangle, Yavapai County, Arizona

DIGITAL GEOLOGIC MAP DGM-80 Arizona Geological Survey www.azgs.az.gov GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE CHINO VALLEY NORTH 7½’ QUADRANGLE, YAVAPAI COUNTY, ARIZONA, V. 1.0 Brian. F. Gootee, Charles A. Ferguson, Jon E. Spencer and Joseph P. Cook December 2010 ARIZONA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Geologic Map of the Chino Valley North 7½' Quadrangle, Yavapai County, Arizona by Brian F. Gootee, Charles A. Ferguson, Jon E. Spencer, and Joe P. Cook Arizona Geological Survey Digital Geologic Map DGM-80 version 1.0 December, 2010 Scale 1:24,000 (1 sheet, with text) Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress St., #100, Tucson, Arizona 85701 This geologic map was funded in part by the USGS National Cooperative Geologic Mapping Program, award no. 08HQAG0093. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Government. Table of Contents Table of Contents......................................................................................................................... i List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. ii Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Geologic Discussion ................................................................................................................... 3 Quaternary faulting ...........................................................................................................3 -

Upper Granite Creek Watershed Pollutant Reduction Plan

Upper Granite Creek Watershed Pollutant Reduction Plan Prepared for Public Works Department 433 N. Virginia Street Prescott, AZ 86301 Prepared by 4600 E. Washington Street, Suite 600 Phoenix, Arizona 85034 November 2020 Upper Granite Creek Watershed Pollutant Reduction Plan City of Prescott Public Works Department Prescott, Arizona Submitted to: City of Prescott Prescott, Arizona Submitted by: Wood Environment & Infrastructure Solutions, Inc. Phoenix, Arizona November 2020 Project No. 3720156008 November 30, 2020 Project No. 3720156008 Contract No. 2015-184 City of Prescott Public Works Department 430 North Virginia Street Prescott, Arizona 86301 Attn: Ben Burns, City of Prescott Matt Killeen, City of Prescott Section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act (CWA) requires that states compile a list of surface waters that do not meet applicable water quality standards (WQS). The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) then must develop Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) for waterbodies on the 303(d) List. TMDLs set the amount of the given pollutant(s) that the waterbody can withstand without creating an impairment of that surface water’s designated beneficial use(s). The City of Prescott (City) is named in two TMDLs, identified as: • Watson Lake TMDL: Total Nitrogen, Dissolved Oxygen (DO), pH & Total Phosphorus Targets - Finalized February 2015 (Open File Report OFR-14-03) • Final Upper Granite Creek Watershed Escherichia coli (E. coli) TMDL November 2015 (Open File Report 14-08) Since 2015, Wood Environment & Infrastructure Solutions, Inc (Wood), has been supporting the City by performing a wide range of activities. The overall purpose of these activities was to evaluate and model pollutant reduction activities and present recommendations in the Upper Granite Creek Watershed Pollutant Reduction Plan (WPRP) and Watson Lake Reservoir Lake Management Plan (LMP). -

443 Subpart D—Federally Promulgated Water Quality Standards

Environmental Protection Agency § 131.33 Subpart D—Federally Promulgated of streams located in Indian country, Water Quality Standards or as may be modified by the Regional Administrator, EPA Region X, pursu- § 131.31 Arizona. ant to paragraph (a)(3) of this section, ° (a) [Reserved] a temperature criterion of 10 C, ex- (b) The following waters have, in ad- pressed as an average of daily max- dition to the uses designated by the imum temperatures over a seven-day State, the designated use of fish con- period, applies to the waterbodies iden- sumption as defined in R18–11–101 tified in paragraph (a)(2) of this section (which is available from the Arizona during the months of June, July, Au- Department of Environmental Quality, gust and September. Water Quality Division, 3033 North (2) The following waters are pro- Central Ave., Phoenix, AZ 85012): tected for bull trout spawning and rearing: COLORADO MAIN STEM RIVER (i) BOISE-MORE BASIN: Devils BASIN: Creek, East Fork Sheep Creek, Sheep Hualapai Wash MIDDLE GILA RIVER BASIN: Creek. Agua Fria River (Camelback Road to (ii) BROWNLEE RESERVOIR BASIN: Avondale WWTP) Crooked River, Indian Creek. Galena Gulch (iii) CLEARWATER BASIN: Big Can- Gila River (Felix Road to the Salt yon Creek, Cougar Creek, Feather River) Creek, Laguna Creek, Lolo Creek, Queen Creek (Headwaters to the Su- Orofino Creek, Talapus Creek, West perior WWTP) Fork Potlatch River. Queen Creek (Below Potts Canyon) (iv) COEUR D’ALENE LAKE BASIN: SAN PEDRO RIVER BASIN: Cougar Creek, Fernan Creek, Kid Copper Creek Creek, Mica Creek, South Fork Mica SANTA CRUZ RIVER BASIN: Creek, Squaw Creek, Turner Creek. -

Outfalls Inspected FY 2020 898997 Northcentral I‐15 9.13 Virgin River

Outfalls inspected FY 2020 Outfall ID District Route MilePost Receiving water Impaired OAW 898997 Northcentral I‐15 9.13 Virgin River 985778 Southcentral I‐10 289.18 Cienega Creek 986825 Southcentral I‐10 288.82 Cienega Creek 1006202 Southcentral I‐10 284.96 Davidson Canyon 1006204 Southcentral I‐10 284.28 Davidson Canyon 1006274 Southcentral I‐10 284.41 Davidson Canyon 1006380 Southcentral I‐10 284.17 Davidson Canyon 1006409 Southcentral I‐10 284.29 Davidson Canyon 1017172 Southcentral SR 77 71.81 Rillito Creek 1017220 Southeast US 191 153.58 Gila River 1058178 Northcentral I‐17 339.85 Sinclair Wash 1062492 Northcentral SR 89A 382.28 Oak Creek 1069543 Northcentral I‐15 9.3 Virgin River 1069544 Northcentral I‐15 9.31 Virgin River 1069545 Northcentral I‐15 9.35 Virgin River 1069546 Northcentral I‐15 9.36 Virgin River 1069547 Northcentral I‐15 9.37 Virgin River 1069548 Northcentral I‐15 9.43 Virgin River 1069550 Northcentral I‐15 9.46 Virgin River 1485571 Northwest SR 89 306.41 Granite Creek 1486080 Northwest SR 89 306.33 Granite Creek 1486083 Northwest SR 89 306.48 Granite Creek 1488480 Northwest SR 69 287.98 Lynx Creek 1510550 Southcentral SR 77 79.84 Canada del Oro 1510619 Southeast US 191 153.43 Gila River 1512473 Central SR 202L 5.9 Salt River 1512474 Central SR 202L 7.99 Salt River 1512475 Central SR 202L 8.3 Salt River 1512476 Central SR 202L 8.45 Salt River 1512477 Central SR 202L 14.45 Salt River 1512486 Central SR 101L 51.38 Salt River 1512487 Central SR 101L 51.58 Salt River 1512537 Central SR 51 6.99 Salt -

Arizona Historic Bridge Inventory

STATE OF ARIZONA HISTORIC PROMINVENTORY FORM Granite Creek Bridge mumy YaTapcd inventorynurh OW42 milwst 318.13 invmtory rout. SR 88 A Iocabn 0.3 rnl E Id SR 89 Came imsdMte Creek cityhriciniv Preston USGS quadrangle hot! district 85 Ul'M referem 12.370057.3831113 STRUCTURAL INFORMATION main span number 2 main span type 104 appr, span number 0 appr. vantype degrea of skew 0 guardrail type 6 main span lhgth 43.0 tuperstructve concrete three-beamdeck girder structure length 89.0 sbstrmture concrete abutmenb, wlngwalls and pier roadway width 20.1 floarldeddng concrete deck swumrre width 23.8 othn fuWr ateel TMebeam guard& HISTORICAL INFORMATION eonmuetlondete 1922 desIgnsr/snginw Adzona Highway Dement projes number FAP 19 buildn1eon~actw Windsor, Coleman & Khg information wwce ADCYT Mge records structure owner Arizona Department of Tmnsportatlon altnakn datds) m1980 ahations steel Thrie beam guardrails lnstcrlled NATIOW REGISTER NUATION For additional informakn, sw "Vehicular Bridges in Nina1880-1964" Nebnal Reglrthr Multiple Property Dosumentation Form inventory rmre 61 NRW eligibility ebglble NRH crltsris A- 0- Cx signtf, statement excellent example of early state standard brldge hpe FORM COMRElED BY Clayton B. hr,Prindpal FRASERdeeign 420 South County Road 23E Loveland, Colorado 80537 31 October MXl4 642 FRASERDESIGN GRANITE CREEK BRIDGE ~lruclvoNa w d.t. d phota: November 20G2 visw &&en north northwest +t~N: 02.1 1.263 02.11.264 FRASERDESIGN GRANITE CREEK BRIDGE CONSTRUCTON HISTORY In 1920 the Arizona Highway Department undertook an improvement of the highway linking Prescott and Jerome. AHD designated this construction as Federal Aid Project 19, to be jointly funded by the state and the U.S. -

Comments on DEIS Volume 2, Appendix C: Wild and Scenic Rivers Evaluation for the Inyo, Sequoia, and Sierra National Forests

Exhibit VIII.1-1 Comments on DEIS Volume 2, Appendix C: Wild and Scenic Rivers Evaluation for the Inyo, Sequoia, and Sierra National Forests General Comments on Evaluation Process The Forest Service deserves recognition for conducting a comprehensive evaluation of potential Wild & Scenic Rivers (WSRs) in the Forest Plans Revision (FPR) process. We appreciate that the agency incorporated its previously completed inventories, eligibility findings, and suitability recommendations. We also greatly appreciate that the Inyo and Sierra Forests determined additional streams to be eligible. However, we identified a number of problems with Appendix C that require attention – not the least of which is the Sequoia Forest’s dismal (in comparison to the Inyo and Sierra) inventory and evaluation results, which failed to identify any new eligible stream segments. We also appreciated the opportunity to review and comment on the preliminary inventory and evaluation in February 2016. However, we are disappointed to find that few of the points raised in our 26 pages of detailed comments were addressed in Appendix C. So these comments are somewhat duplicative to the ones submitted by CalWild et al dated Feb. 1, 2016, which are hereby incorporate by reference. Be advised that new additional points are included in these comments. WSR Inventory/Evaluation Comments Applicable To All Three Forests Unnamed Streams Not Inventoried (DEIS Vol. 2, App. C, pg. 379) – The inventory process appears to be restricted to rivers and streams named on 7.5-minute USGS quad maps. There is nothing in the Forest Service Handbook (FSH), federal guidelines, or in federal law that limits WSR inventories and evaluations to only named streams. -

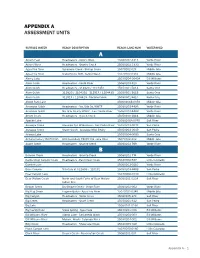

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED A Ackers East Headwaters - Ackers West 15060202-3313 Verde River Ackers West Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-3333 Verde River Agua Fria River Sycamore Creek - Bishop Creek 15070102-023 Middle Gila Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo Lake 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alder Creek Headwaters - Verde River 15060203-910 Verde River Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820 / 1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - Aravaipa Wild. Bndry 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arizona Canal (15070102) HUC boundary 15070102 - Gila River 15070102-202 Middle Gila Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River B Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bass Canyon Tributary at 322606 / 110131 15050203-899B San Pedro -

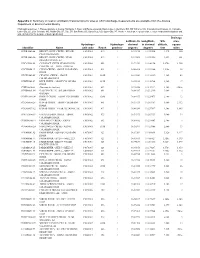

USGS Open-File Report 2009-1269, Appendix 2

Appendix 2. Summary of location and basin characteristics for sites at which discharge measurements are available from the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality [Hydrologic provinces: 1, Plateau Uplands; 2, Central Highlands; 3, Basin and Range Lowlands. Basin codes in Identifiers: BW, Bill Williams; CG, Colorado-Grand Canyon; Cl, Colorado- Lower Gila; LC, Little Colorado; MG, Middle Gila; SR, Salt; SP, San Pedro; SC, Santa Cruz; UG, Upper Gila; VR, Verde. <, less than; >, greater than; e, value not present in database and was estimated for the purpose of model predictions] Drainage Latitude, in Longitude, Site area, Hydrologic Hydrologic decimal in decimal altitude, square Identifier Name unit code Reach province degrees degrees feet miles CGBRA000.44 BRIGHT ANGEL CREEK - BELOW 15010001 019 1 36.10236 112.09514 2,520 100 PHANTOM RANCH CGBRA000.50 BRIGHT ANGEL CREEK - NEAR 15010001 019 1 36.10306 112.09556 2,452 101 GRAND CANYON, AZ CGCAT056.68 CATARACT CREEK NEAR GRAND 15010004 005 1 35.72333 112.44194 5,470e 1,200 CANYON, AZ USGS 09404100 CGCLE000.19 CLEAR CREEK - ABOVE COLORADO 15010001 025 1 36.08414 112.03344 2,520e 36 RIVER CGCRY000.05 CRYSTAL CREEK - ABOVE 15010002 018B 1 36.13542 112.24319 2,360 43 COLORADO RIVER CGDEE000.07 DEER CREEK - ABOVE COLORADO 15010002 019B 1 36.38931 112.50764 1,960 17 RIVER CGDIA000.06 (No name in database) 15010002 002 1 35.76556 113.37222 1,340 <946e CGGDN001.09 GARGEN CREEK - BELOW INDIAN 15010002 841 1 36.08347 112.12319 3,600 4 GARDEN CGHRM000.08 HERMIT CREEK - ABOVE COLORADO 15010002 020B -

The Verde River, One of the Last Perennial Southwestern Rivers, Is in Danger of Running Dry. You Can Help Save It

FY 2019 ANNUAL REPORT THE VERDE RIVER, ONE OF THE LAST PERENNIAL SOUTHWESTERN RIVERS, IS IN DANGER OF RUNNING DRY. YOU CAN HELP SAVE IT. SUSTAINING FLOWS RESTORING HABITAT PROMOTING COMMUNITY 2 2 STAFF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Nancy L.C. Steele, Executive Director Chip Norton, President Maxwell Wilson, Manager, Sustaining Flows Tony Goia, Vice President Tracy Stephens, Manager, Habitat Restoration Jeni O'Callaghan, Secretary Matthew Wilson, Manager, Habitat Resortation Brent Bitz, Treasurer Karon Leigh, Manager, Marketing & Communications Peggy Chaikin Matthew Gilbert, Financial Services Administrator Max Castillo Virginia Weis, Administrative Assistant Susan Culp Elaine Nichols, Habitat Restoration Field Supervisor Jennifer Diffley Laura Jones, Community Engagement Coordinator Marsha Foutz Isaac Dudley, Business Development Coordinator Siera Russell Tod Young, Communications Coordinator Harry Sweet Benjamin Kowalewski, Habitat Resortation Coordinator Emily Garding, GIS Specialist con't next page If you love the Verde River and its tributaries, such as Granite Creek, Sycamore Creek, Oak Creek, and Fossil Creek, please ACT NOW TO HELP Friends work collaboratively to restore habitat, sustain flows, and promote community stewardship. DONATE, VOLUNTEER, & LEARN at VERDERIVER.ORG 3 LETTER FROM THE 3 “Working collaboratively for a healthy Verde River.” PRESIDENT This has been the modus operandi of Friends since our inception in 2007. Partnerships + Collaborations I've learned that in order to achieve our vision of a healthy Verde River flowing through healthy communities, we need to build even more partnerships going forward. The more things change, the more they remain the same. In 2007, the founders of Friends relied upon a small group of volunteers to donate their passion and their time to complete river projects in the Verde River Greenway Natu- ral Area. -

Prescott Active Management Area

Virtual Tour Prescott AMA Active Management Area 2200 EastHillsdale Road 2200 Prescott, AZ 86301 www.azwater.gov Prescott (928) 778-7202 Prescott AMA r u o General Groundwater Facts T al u t r • New AMAs can be i • The Groundwater V Management Code was designated either by passed in June of 1980 determination by the and established the four director (45-412) or by initial Active Management petition of 10% of the Areas (AMA): Phoenix, registered voters within Tucson, Pinal and the boundary of the Prescott. proposed AMA (45-415). • The Prescott, Phoenix and • Each AMA shall have a Tucson AMAs have a goal groundwater user’s of safe-yield by 2025. advisory council (GUAC) of five members who are appointed by the Governor. 2 Prescott AMA r u o Active Management Areas (AMA) and T al Irrigation Non-expansion Areas (INA) u t r i V Arizona Prescott AMA 485 mile2 ~ 20,000 AF water use Santa Cruz AMA 750 mile2 ~ 20,000 AF water use Tucson AMA 3,800 mile2 ~ 300,000 AF water use Pinal AMA 4,000 mile2 ~ 800,000 AF water use Phoenix AMA 5,600 mile2 ~ 2 million AF water use 3 4 Virtual Tour Prescott AMA Prescott AMA r u o Prescott AMA T al u • The Prescott AMA, 100 miles t • Precipitation varies from 13 to 25 r i north & west of Phoenix, inches per year V comprises 485 square miles in central Yavapai County, Arizona • 2,900,000 acre feet of groundwater in storage in local sub-basins* • Elevation ranges from 4400’ to 7800’ above sea level • The 2003 to 2004 mean annual water-level decline rate was -2.7 • Vegetation varies from high feet* desert grasslands to conifer forests • Broad alluvial basins ringed by fault block mountains 5 *Prescott Active Management Area 2003-2004 Hydrologic Monitoring Report Prescott AMA r u o T Precipitation al u t r 25 in. -

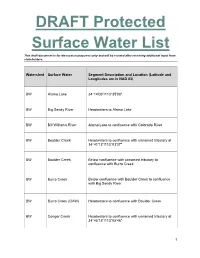

DRAFT Protected Surface Water List

DRAFT Protected Surface Water List This draft document is for discussion purposes only and will be revised after receiving additional input from stakeholders. Watershed Surface Water Segment Description and Location (Latitude and Longitudes are in NAD 83) BW Alamo Lake 34°14'06"/113°35'00" BW Big Sandy River Headwaters to Alamo Lake BW Bill Williams River Alamo Lake to confluence with Colorado River BW Boulder Creek Headwaters to confluence with unnamed tributary at 34°41'13"/113°03'37" BW Boulder Creek Below confluence with unnamed tributary to confluence with Burro Creek BW Burro Creek Below confluence with Boulder Creek to confluence with Big Sandy River BW Burro Creek (OAW) Headwaters to confluence with Boulder Creek BW Conger Creek Headwaters to confluence with unnamed tributary at 34°45'15"/113°05'46" 1 This draft document is for discussion purposes only and will be revised after receiving additional input from stakeholders. BW Conger Creek Below confluence with unnamed tributary to confluence with Burro Creek BW Copper Basin Wash Headwaters to confluence with unnamed tributary at 34°28'12"/112°35'33" BW Cottonwood Canyon Headwaters to Bear Trap Spring BW Cottonwood Canyon Below Bear Trap Spring to confluence at Smith Canyon Sycamore Creek BW Date Creek Headwaters to confluence with Santa Maria River BW Francis Creek (OAW) Headwaters to confluence with Burro Creek BW Kirkland Creek Headwaters to confluence with Santa Maria River BW Knight Creek Headwaters to confluence with Big Sandy River BW Peeples Canyon Headwaters to confluence with Santa Maria River (OAW) BW Santa Maria River Headwaters to Alamo Lake BW Trout Creek Headwaters to confluence with unnamed tributary at 35°06'47''/113°13'01'' 2 This draft document is for discussion purposes only and will be revised after receiving additional input from stakeholders. -

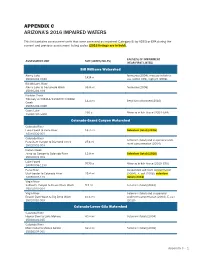

Appendix C Arizona's 2016 Impaired Waters

APPENDIX C ARIZONA’S 2016 IMPAIRED WATERS This list contains assessment units that were assessed as impaired (Category 5) by ADEQ or EPA during the current and previous assessment listing cycles (2016 listings are in bold). CAUSE(S) OF IMPAIRMENT ASSESSMENT UNIT SIZE (ACRES/MILES) (YEAR FIRST LISTED) Bill Williams Watershed Alamo Lake Ammonia (2004), mercury in fish tis- 1414 a 15030204-0040 sue (2002- EPA), high pH (1996) Bill Williams River Alamo Lake to Castaneda Wash 35.9 mi Ammonia (2006) 15030204-003 Boulder Creek Tributary at 344114/1131800 to Wilder 14.4 mi Beryllium (dissolved)(2010) Creek 15030202-006B Coors Lake 230 a Mercury in fish tissue (2004- EPA) 15030202-5000 Colorado-Grand Canyon Watershed Colorado River Lake Powell to Paria River 16.3 mi Selenium (total) (2016) 14070006-001 Colorado River Selenium (total) and suspended sedi- Parashant Canyon to Diamond Creek 27.6 mi ment concentration (2004) 15010002-003 Kanab Creek Jump-up Canyon to Colorado River 12.8 m Selenium (total) (2016) 15010003-001 Lake Powell 9770 a Mercury in fish tissue (2010- EPA) 14070006-1130 Paria River Suspended sediment concentration Utah border to Colorado River 29.4 mi (2004), E. coli (2006), selenium 14070007-123 (total) (2016) Virgin River Sullivan’s Canyon to Beaver Dam Wash 9.7 mi Selenium (total) (2012) 15010010-004 Virgin River Selenium (total) and suspended Beaver Dam Wash to Big Bend Wash 10.1 mi sediment concentration (2004), E. coli 15010010-003 (2010) Colorado-Lower Gila Watershed Colorado River Hoover Dam to Lake Mohave 40.4 mi Selenium