Differences in the Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Copy The World Bank Implementation Status & Results Report Sichuan Chongqing Cooperation: Guang'an Demonstration Area Infrastructure Development Project (P133456) Sichuan Chongqing Cooperation: Guang'an Demonstration Area Infrastructure Development Project (P133456) EAST ASIA AND PACIFIC | China | Social, Urban, Rural and Resilience Global Practice Global Practice | IBRD/IDA | Investment Project Financing | FY 2015 | Seq No: 2 | ARCHIVED on 10-Dec-2015 | ISR21618 | Public Disclosure Authorized Implementing Agencies: Guangan Municipality Key Dates Key Project Dates Bank Approval Date:16-Mar-2015 Effectiveness Date:27-Aug-2015 Planned Mid Term Review Date:31-Oct-2017 Actual Mid-Term Review Date:-- Original Closing Date:30-Sep-2020 Revised Closing Date:30-Sep-2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The Project Development Objective is to improve Linshui County and Qianfeng District infrastructure and investment support services. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project Objective? No PHRPDODEL Public Disclosure Authorized Components Name Technical Assistance:(Cost $0.60 M) Linshui County Town:(Cost $64.39 M) Qianfeng District Town:(Cost $42.62 M) Project Management and Capacity Building:(Cost $1.77 M) Overall Ratings Name Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Substantial Substantial 12/10/2015 Page 1 of 9 Public Disclosure Copy Public Disclosure Copy The World Bank Implementation Status & Results Report Sichuan Chongqing Cooperation: Guang'an Demonstration Area Infrastructure Development Project (P133456) Implementation Status and Key Decisions The project is making good progress and is on track to improve Linshui County and Qianfeng District infrastructure and investment support services. -

Since the Reform and Opening Up1 1

Int. Statistical Inst.: Proc. 58th World Statistical Congress, 2011, Dublin (Session CPS020) p.6378 Research of Acceleration Urbanization Impacts on Resources and Environment in Sichuan Province Caimo,Teng National Bureau of Statistics of China, Survey Organizations of Sichuan No.31, the East Route, Qingjiang Road Chengdu, China, 610072 E-mail: [email protected] Since the reform and opening up, the rapid development of economic society and the rise ceaselessly of urbanization in Sichuan play an important role for material civilization and spiritual civilization, but also bring influence for resources and environment, this paper give an in-depth analysis about this. Ⅰ. The Main Characteristics of the Urbanization Development in Sichuan The reflection of urbanization in essence is from the industry cluster to population cluster., we tend to divided the process of urbanization into four stages, 1949-1978 is the first stage, 1978 – 1990 is the second stage, 1990 -2000 is the third stage, After the year of 2000 is the fourth stage. In view the particularities of the first phase, this paper researches mainly after three stages. 1. The level of the urbanization enhances unceasingly. With the reform and opening-up and the rapid development of social economy, the urbanization in Sichuan has significant achievements. The average annual growth of the level of urbanization is 0.8 percent in the twelve years of the second stage. The average annual growth in the third stage and the four stages is individually 0.5 and 1.3 percentage. The average annual growth of urbanization in the fourth stage is faster respectively 0.5 and 0.8 percent than the previous two stages which reflects obviously the rapid rise of the urbanization after the fourth stage in Sichuan. -

Water Service Delivery Reform in China: Safeguarding the Interests of the Poor

ANNALS OF ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 13-2, 463{487 (2012) Water Service Delivery Reform in China: Safeguarding the Interests of the Poor Denis Nitikin The World Bank, USA Chunli Shen University of Maryland, College Park, USA (Janey) Qian Wang* San Francisco State University, USA E-mail: [email protected] and Heng-fu Zou CEMA, Central University of Finance and Economics Shenzhen University Peking University Wuhan University The World Bank China faces a water scarcity problem that is severe by international stan- dards. Many factors, including rapid urbanization and environmental degra- dation etc, have been challenging the water service delivery in China. Since water scarcity and quality have impact on the poor, reforms to the water ser- vice provision can produce substantial improvements in the living standard of the economically disadvantaged groups. The objective of this study is to crit- ically evaluate the strengths and weakness of China's current water financing and delivering system, with a focus on safeguarding the interests of the poor, and to offer insight into possible solutions. Key Words: Water administration; Water pricing; Water financing. JEL Classification Numbers: Q25, I31. * Corresponding author: (Janey) Qian Wang, Assistant Professor 463 1529-7373/2012 All rights of reproduction in any form reserved. 464 DENIS NITIKIN, CHUNLI SHEN, QIAN WANG, AND HENG-FU ZOU 1. INTRODUCTION Rapidly increasing scarcity and deteriorating of quality of water resources present a serious challenge to China. These problems, to a substantial de- gree, are caused by demographic factors and economic growth, the processes which one cannot easily control at will. Pressing environmental problem- s call for radical policy measures to curb water demand and to increase environmentally sustainable water supply. -

Source Rupture Process of Lushan MS7.0 Earthquake, Sichuan, China and Its Tectonic Implications

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Article SPECIAL TOPIC October 2013 Vol.58 No.28-29: 34443450 Coseismic Deformation and Rupture Processes of the 2013 Lushan Earthquake doi: 10.1007/s11434-013-6017-6 Source rupture process of Lushan MS7.0 earthquake, Sichuan, China and its tectonic implications ZHAO CuiPing1*, ZHOU LianQing1 & CHEN ZhangLi2 1 Institute of Earthquake Science, China Earthquake Administration, Beijing 100036, China; 2 China Earthquake Administration, Beijing 100036, China Received June 9, 2013; accepted July 8, 2013; published online August 22, 2013 The source rupture process of the MS7.0 Lushan earthquake was here evaluated using 40 long-period P waveforms with even azimuth coverage of stations. Results reveal that the rupture process of the Lushan MS7.0 event to be simpler than that of the Wenchuan earthquake and also showed significant differences between the two rupture processes. The whole rupture process 19 lasted 36 s and most of the moment was released within the first 13 s. The total released moment is 1.9×10 N m with MW=6.8. Rupture propagated upwards and bilaterally to both sides from the initial point, resulting in a large slip region of 40 km×30 km, with the maximum slip of 1.8 m, located above the initial point. No surface displacement was estimated around the epicenter, but displacement was observed about 20 km NE and SW directions of the epicenter. Both showed slips of less than 40 cm. The rup- ture suddenly stopped at 20 km NE of the initial point. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

NPC Members of Yilong County Visited PFGHL Nanchong Factory

NPC Members of Yilong County Visited PFGHL Nanchong Factory On the morning of July 25, 2017, the delegates participating in the second session of the 17th Yilong County People's Congress gathered to visit the construction and development of the county seat and Industrial Park of Yilong County, Nanchong City of Sichuan Province. The county government officers including Guo Zonghai, Zheng Yuanqin, Li Jun, Deng Bulin, Leng Guanjun, Xu Yuan, Wu Kaihong, Chen Zhi, and Tang Guoying joined the visit and were informed of the details regarding the county’s key project of PFGHL Nanchong Factory and Hong Kong investments. After conducting detailed inspections of the facilities, the county government officers were confident of the immense developmental potential of the PFGHL Nanchong Factory. They provided praise for the achievements of the factory and displayed encouragement for the continued progression of the project. During the visit, the Factory Manager initially briefed the government officials and delegates on the current state of PFGHL Group and its Nanchong factory, namely the PFGHL Nanchong Factory. He said, "PFGHL is one of the leading one-stop international service providers in China’s garment industry. Its factories are distributed across the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong, forming a large interconnected garment manufacturing and service network. Its products are distributed internationally in a timely manner". Subsequently, the Factory Manager focused on introducing the efforts made by the PFGHL Nanchong Factory in environmental protection. The factory is operated to be in full compliance with Yilong County’s policy of green development. It is dedicated to implementing the county’s principle of protecting the Jialing River, its water bodies, and the surrounding hills. -

Earthquake Phenomenology from the Field the April 20, 2013, Lushan Earthquake Springerbriefs in Earth Sciences

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN EARTH SCIENCES Zhongliang Wu Changsheng Jiang Xiaojun Li Guangjun Li Zhifeng Ding Earthquake Phenomenology from the Field The April 20, 2013, Lushan Earthquake SpringerBriefs in Earth Sciences For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/8897 Zhongliang Wu · Changsheng Jiang · Xiaojun Li Guangjun Li · Zhifeng Ding Earthquake Phenomenology from the Field The April 20, 2013, Lushan Earthquake 1 3 Zhongliang Wu Guangjun Li Changsheng Jiang Earthquake Administration of Sichuan Xiaojun Li Province Zhifeng Ding Chengdu China Earthquake Administration China Institute of Geophysics Beijing China ISSN 2191-5369 ISSN 2191-5377 (electronic) ISBN 978-981-4585-13-2 ISBN 978-981-4585-15-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-981-4585-15-6 Springer Singapore Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014939941 © The Author(s) 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. -

Determinantsofpublicgoodsinve

J. Mt. Sci. (2014) 11(3): 816-824 e-mail: [email protected] http://jms.imde.ac.cn DOI: 10.1007/s11629-013-2244-1 Determinants of Public Goods Investment in Rural Communities in Mountainous Areas of Sichuan Province, China GUO Shi-li1,2,4, LIU Shao-quan1,*, LUO Ren-fu3, ZHANG Lin-xiu3 1 Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu 610041, China 2 Economic Research Center for Western China, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, Chengdu 610074, China 3 Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China 4 Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China * Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected]; First author, e-mail: [email protected] Citation: Guo SL, Liu SQ, Luo RF, Zhang LX (2014) Determinants of public goods investment in rural communities in mountainous areas of Sichuan Province, China. Journal of Mountain Science 11(3). DOI: 10.1007/s11629-013-2244-1 © Science Press and Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, CAS and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 Abstract: This study aims to investigate two Investment; Regression Analysis; Rural Development important issues: what are the determinants of public goods investment and what is the government’s investment behavior in mountainous areas. The Introduction impacts of natural conditions, target, and demand elements on public goods investment are analyzed Public goods which are non-competitive on the with statistical method, and the determinants of public goods investment in the areas are obtained by consumption and non-exclusive on the income, using population-weighted and stepwise regression refers to the goods and services produced and models with Eviews6.0 software with survey data in provided by the government (public sector) to meet 2008 and calculated data based on GIS of 20 typical the common needs of the people. -

China's Public Participation in Environmental Decision-Making

sustainability Article Decision-Maker-Oriented VS. Collaboration: China’s Public Participation in Environmental Decision-Making Lu Feng 1, Qimei Wu 2, Weijun Wu 3 and Wenjie Liao 4,* 1 School of Law, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610065, China; [email protected] 2 Judicial Bureau of Tongchuan District, Dazhou 635000, China; [email protected] 3 School of Public Affairs and Administration, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu 611731, China; [email protected] 4 Institute of New Energy and Low-Carbon Technology, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610065, China * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +86-28-6213-8375 Received: 31 October 2019; Accepted: 16 January 2020; Published: 12 February 2020 Abstract: Public participation in environmental decision-making (EDM) has been broadly discussed. However, few recent studies in English have focused on the participation subject, scope, ways, and procedure in the EDM of developing countries such as China in the worldwide governance transformation. This study aims to provide an overview of public participation in EDM in China, thus elucidating both the legislation and practice of public participation in EDM in China to a broader audience, as such an overview has not yet been provided. At the beginning of this article, we clarify the key definitions of EDM, public participation and the public, and establish an analytical framework for analyzing public participation in EDM in China. We analyze the scope of the public, the participation scope, ways of participating, and participation procedure in EDM in legislation and practice, through document analysis and empirical survey. We then comment on challenges for public participation in EDM in China—including low public participation in EDM, narrow scope of participation, unbalanced ways of participation, and unreasonable participation procedure. -

Crustal Stress State and Seismic Hazard Along Southwest Segment of the Longmenshan Thrust Belt After Wenchuan Earthquake

Journal of Earth Science, Vol. 25, No. 4, p. 676–688, August 2014 ISSN 1674-487X Printed in China DOI: 10.1007/s12583-014-0457-z Crustal Stress State and Seismic Hazard along Southwest Segment of the Longmenshan Thrust Belt after Wenchuan Earthquake Xianghui Qin*, Chengxuan Tan, Qunce Chen, Manlu Wu, Chengjun Feng Institute of Geomechanics, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100081, China; Key Laboratory of Neotectonic Movement & Geohazard, Ministry of Land and Resources, Beijing 100081, China ABSTRACT: The crustal stress and seismic hazard estimation along the southwest segment of the Longmenshan thrust belt after the Wenchuan Earthquake was conducted by hydraulic fracturing for in-situ stress measurements in four boreholes at the Ridi, Wasigou, Dahegou, and Baoxing sites in 2003, 2008, and 2010. The data reveals relatively high crustal stresses in the Kangding region (Ridi, Wasigou, and Dahegou sites) before and after the Wenchuan Earthquake, while the stresses were relatively low in the short time after the earthquake. The crustal stress in the southwest of the Longmenshan thrust belt, especially in the Kangding region, may not have been totally released during the earthquake, and has since increased. Furthermore, the Coulomb failure criterion and Byerlee’s law are adopted to analyzed in-situ stress data and its implications for fault activity along the southwest segment. The magnitudes of in-situ stresses are still close to or exceed the expected lower bound for fault activity, revealing that the studied region is likely to be active in the future. From the conclusions drawn from our and other methods, the southwest segment of the Longmenshan thrust belt, especially the Baoxing region, may present a future seismic hazard. -

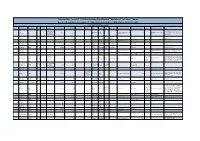

Documented Cases of 1,352 Falun Gong Practitioners "Sentenced" to Prison Camps

Documented Cases of 1,352 Falun Gong Practitioners "Sentenced" to Prison Camps Based on Reports Received January - December 2009, Listed in Descending Order by Sentence Length Falun Dafa Information Center Case # Name (Pinyin)2 Name (Chinese) Age Gender Occupation Date of Detention Date of Sentencing Sentence length Charges City Province Court Judge's name Place currently detained Scheduled date of release Lawyer Initial place of detention Notes Employee of No.8 Arrested with his wife at his mother-in-law's Mine of the Coal Pingdingshan Henan Zhengzhou Prison in Xinmi City, Pingdingshan City Detention 1 Liu Gang 刘刚 m 18-May-08 early 2009 18 2027 home; transferred to current prison around Corporation of City Province Henan Province Center March 18, 2009 Pingdingshan City Nong'an Nong'an 2 Wei Cheng 魏成 37 m 27-Sep-07 27-Mar-09 18 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2027 Arrested from home; County Court Zhejiang Fuyang Zhejiang Province Women's 3 Jin Meihua 金美华 47 f 19-Nov-08 15 Fuyang City November, 2023 Province City Court Prison Nong'an Nong'an 4 Han Xixiang 韩希祥 42 m Sep-07 27-Mar-09 14 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2023 Arrested from home; County Court Nong'an Nong'an 5 Li Fengming 李凤明 45 m 27-Sep-07 27-Mar-09 14 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2023 Arrested from home; County Court Arrested from home; detained until late April Liaoning Liaoning Province Women's Fushun Nangou Detention 6 Qi Huishu 齐会书 f 24-May-08 Apr-09 14 Fushun City 2023 2009, and then sentenced in secret and Province Prison Center transferred to current prison. -

Sauropod and Small Theropod Tracks from the Lower Jurassic Ziliujing Formation of Zigong City, Sichuan, China, with an Overview

Ichnos, 21:119–130, 2014 Copyright Ó Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1042-0940 print / 1563-5236 online DOI: 10.1080/10420940.2014.909352 Sauropod and Small Theropod Tracks from the Lower Jurassic Ziliujing Formation of Zigong City, Sichuan, China, with an Overview of Triassic–Jurassic Dinosaur Fossils and Footprints of the Sichuan Basin Lida Xing,1 Guangzhao Peng,2 Yong Ye,2 Martin G. Lockley,3 Hendrik Klein,4 W. Scott Persons IV,5 Jianping Zhang,1 Chunkang Shu,2 and Baoqiao Hao2 1School of the Earth Sciences and Resources, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China 2Zigong Dinosaur Museum, Zigong, Sichuan, China 3Dinosaur Trackers Research Group, University of Colorado, Denver, Colorado, USA 4Saurierwelt Palaontologisches€ Museum, Neumarkt, Germany 5Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada Keywords Grallator, Parabrontopodus, Hejie tracksite, Ma’anshan A dinosaur footprint assemblage from the Lower Jurassic Member, Zigong Ziliujing Formation of Zigong City, Sichuan, China, comprises about 300 tracks of small tridactyl theropods and large sauropods preserved as concave epireliefs (natural molds). The INTRODUCTION theropod footprints show similarities with both the ichnogenera Zigong is famous for the Middle Jurassic Shunosaurus Grallator and Jialingpus. Three different morphotypes are fauna and the Late Jurassic Mamenchisaurus fauna. However, present, probably related to different substrate conditions and extramorphological variation. A peculiar preservational feature fossils from the Early Jurassic and the Late Triassic are com- in a morphotype that reflects a gracile trackmaker with paratively rare. Previously reported Early Jurassic fossils extremely slender digits, is the presence of a convex epirelief that include fragmentary prosauropod and sauropod skeletal occurs at the bottom of the concave digit impressions.