Community Building at the Time of Nargis: the ASEAN Response, In: Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 28, 4, 3-22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNDP Myanmar Responds to Cyclone Nargis

UNDP Myanmar responds MATTERS OF FACT to Cyclone Nargis • 40 UNDP and its implementing partner NGO PACT offices in the Ayeyarwady Delta UNDP moved into action within 24 hours after Cyclone • 23 field teams active in the worst affected areas Nargis hit Myanmar on 2-3 May. The storm carved a • 500 national staff and project personnel working in the path of destruction that left 133,653 dead or missing delta and being mobilized for Cyclone Nargis response and 2.4 million severely affected by the crisis. operations • 5 UNDP offices functioning as ‘base camp’ for UN The cyclone’s 120-mile per hour winds and resulting organizations and international NGOs delivering to, and storm surge were particularly devastating in the working in Bogale, Mawlamyinegyun, Labutta, Ayeyarwady Delta, where entire villages were flattened. Ngapudaw and Kyaiklat • 2.4 million people severely affected by Cyclone UNDP is the only UN organization with field offices Nargis across Myanmar located in the region, which, prior to the cyclone was • 1.4 million people affected in the Ayeyarwady delta, home to seven million people. UNDP staff and families the hardest hit region of Myanmar experienced the natural disaster first-hand, as did those • 43,241 estimated total beneficiaries from UNDP coordinated relief efforts as of 21 May who work for partner non-governmental organization (NGO) PACT, which lost five of its project personnel. Supporting relief efforts: UNDP sent rotating teams UNDP has 40 functioning field offices in the delta and of national staff to work with and relieve its field staff in current field staff strength of more than 500 five of the affected townships – Bogale, experienced national staff and project personnel, Mawlamyinegyun, Labutta, Ngapudaw and Kyaiklat – including those of PACT. -

UK Aid in Burma

UKAID In BUrmA What is international development? also renewed the government’s International development is about commitment to increase UK aid to helping people fight poverty. Thanks 0.7% of national income from 2013. to the efforts of governments and people around the world, there are What is the Department for 500 million fewer people living in International Development? poverty today than there were 25 The Department for International years ago. But there is still much Development (DFID), leads the UK more to do. government’s fight against world poverty. 1.4 billion people still live on less than $1.25 a day. More needs to Since its creation in 1997, DFID has happen to increase incomes, settle helped more than 250 million people conflicts, increase opportunities for lift themselves from poverty and trade, tackle climate change, improve helped 40 million more children to people’s health and their chances to go to primary school. But there is get an education. still much to do to help make a fair, safe and sustainable world for all. Why is the UK government involved? Through its network of offices Each year the UK government helps throughout the world, DFID three million people to lift themselves works with governments of out of poverty. Ridding the world developing countries, charities, of poverty is not just morally right, non‑government organisations, it will make the world a better businesses and international place for everyone. Problems faced organisations, like the United by poor countries affect all of us, Nations, European Commission and including the UK. Britain’s fastest the World Bank, to eliminate global growing export markets are in poor poverty and its causes. -

Inter-Agency Real Time Evaluation of the Response to Cyclone Nargis

Inter-Agency Real Time Evaluation of the Response to Cyclone Nargis 17 December 2008 Robert Turner Jock Baker Dr. Zaw Myo Oo Naing Soe Aye Managed and funded by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA), Policy Development and Studies Branch (PDSB), Evaluation and Studies Section (ESS), on behalf of the Inter Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Contents Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgments.............................................................................................................................................iv Map of Myanmar................................................................................................................................................v 1 Executive Summary...................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction..............................................................................................................................1 1.2 Summary of Key Findings .......................................................................................................1 1.2.1 Consultation and Capacity Building..............................................................................2 1.2.2 Disaster Risk Reduction and Livelihoods .....................................................................2 1.2.3 Coordination..................................................................................................................2 -

Myanmar-Jews.Pdf

8*9** Letter Myanmar-- from After decades of repressive military rule, Burma’s Jewish community has dwindled to about 20 members. Is there hope for its future? A rare look at life inside the isolated country. Story by Jeremy Gillick Photos by Chris Daw As the sun sets in Burma, now known as Myanmar, a small group of Jews descends on the Park Royal Hotel in down town Yangon, formerly Rangoon. I arrive unfashionably early, hoping to steal some private time with Sammy Samuels, the debonair Burmese-American host of the third annual Myan mar Jewish Community Dinner Reception. But apparently it is fashionable for Burmese Jews to arrive late, and Sammy is no where to be found. At 6:30, tuxedoed caterers begin distribut ing glasses of Israeli and French wines to guests socializing in the lobby. I chat briefly with Cho, the daughter of Myanmar’s foreign minister, who professes her love for Israel, and then with an impeccably dressed British diplomat who is superb at making small talk. When I ask if I should be concerned about reporting from such a public location, he points to secret po lice lurking in the corners and suggests steering clear of dis cussing politics. “Once you’ve lived here a while, they’re easy to spot,” he says. At last, Sammy himself strides in. Short with a wide face, kind eyes and dark hair puffed up in the front, his relaxed de meanor belies the gravity of the task ahead of him. He is one of perhaps 20 Jews—many of them elderly or intermarried—left in the entire country. -

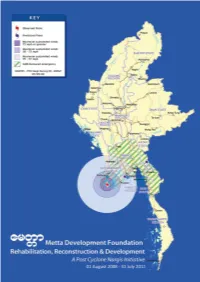

Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development a Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative

Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative 1 2 Metta Development Foundation Table of Contents Forward, Executive Director 2 A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative - Executive Summary 6 01. Introduction – Waves of Change The Ayeyarwady Delta 10 Metta’s Presence in the Delta. The Tsunami 11 02. Cyclone Nargis –The Disaster 12 03. The Emergency Response – Metta on Site 14 04. The Global Proposal 16 The Proposal 16 Connecting Partners - Metta as Hub 17 05. Rehabilitation, Reconstruction and Development August 2008-July 2011 18 Introduction 18 A01 – Relief, Recovery and Capacity Building: Rice and Roofs 18 A02 – Food Security: Sowing and Reaping 26 A03 – Education: For Better Tomorrows 34 A04 – Health: Surviving and Thriving 40 A05 – Disaster Preparedness and Mitigation: Providing and Protecting 44 A06 – Lifeline Systems and Transportation: The Road to Safety 46 Conclusion 06. Local Partners – The Communities in the Delta: Metta Meeting Needs 50 07. International Partners – The Donor Community Meeting Metta: Metta Day 51 08. Reporting and External Evaluation 52 09. Cyclones and Earthquakes – Metta put anew to the Test 55 10. Financial Review 56 11. Beyond Nargis, Beyond the Delta 59 12. Thanks 60 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms 61 Staff Directory 62 Volunteers 65 Annex 1 - The Emergency Response – Metta on Site 68 Annex 2 – Maps 76 Annex 3 – Tables 88 Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative 3 Forword Dear Friends, Colleagues and Partners On the night of 2 May 2008, Cyclone Nargis struck the delta of the Ayeyarwady River, Myanmar’s most densely populated region. The cyclone was at the height of its destructive potential and battered not only the southernmost townships but also the cities of Yangon and Bago before it finally diminished while approaching the mountainous border with Thailand. -

Atmosphere Interactions During Cyclone Nargis

Eos, Vol. 90, No. 7, 17 February 2009 VOLUME 90 NUMBER 7 17 FEBRUARY 2009 EOS, TRANSACTIONS, AMERICAN GEOPHYSICAL UNION PAGES 53–60 storm development. Thus, the timing of Nar- Ocean- Atmosphere Interactions gis was not unusual. Nor was its strength unprecedented: Cyclones of similar inten- sity hit Myanmar in May 1982 and April 2006. During Cyclone Nargis In both instances, landfall was north of the most densely populated parts of the country. PAGES 53–54 as captured by elements of this observing In mid- April 2008, SSTs in the Bay of Ben- system. gal were 29º– 30°C (Figures 2 and 3) and Cyclone Nargis (Figure 1a) made land- tropospheric wind shears were 30% weaker fall in Myanmar (formerly Burma) on 2 May Development of Nargis than normal. Against this backdrop, Nar- 2008 with sustained winds of approximately gis originated as a tropical depression in 210 kilometers per hour, equivalent to a cat- Tropical storms in the Bay of Bengal occur the southeastern Bay of Bengal on 24 April egory 3– 4 hurricane. In addition, Nargis most frequently in October– December with and then began tracking northwestward brought approximately 600 millimeters of a secondary peak in April– May. Relatively toward India. The depression became nearly rain and a storm surge of 3– 4 meters to the high (28º– 30°C) SSTs, a thermo dynamically stationary on encountering a region of cli- low- lying and densely populated Irrawaddy unstable atmosphere, and low tropospheric matologically high tropical cyclone heat River delta. In its wake, the storm left an esti- wind shears favor these seasons for tropical potential (Figure 1c), where it intensifi ed to mated 130,000 dead or missing and more than $10 billion in economic losses. -

Myanmar, Cyclone Nargis: 2 Years On

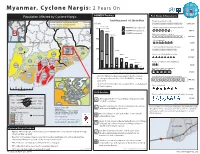

Myanmar, Cyclone Nargis: 2 Years On PONREPP Funding Population Affected by Cyclone Nargis Post-Nargis Achievements Total Requested: US $691million People receiving food aid India Affected Population in Ayeyarwady Division 1,600,000 China $US mil. Affected Population in Yangon Division 800,000 1,100,000 Vietnam Myanmar Total Affected Population 2,400,000 Livlihoods & Laos PONREPP 3 year requirement Nutrition support to malnourished children 200 Food Security Shelter PONREPP 2009 requirement 39,375 Thailand PONREPP 2009 received Education support to children BAY OF Education BENGAL 623,000 Cambodia Yangon Division 150 Schools repaired Ayeyarwady Division 1,500 5700 45000 Community Health Volunteers Trained 11000 11000 20800 34500 17000 100 6100 Health 536 3700 ! 23000 18700 Pathein 19900 100000 156000 WASH Houses receiving shelter assistance 37700 105000 DRR 162,047 96000 50 Protection 34500 178000 Recovery Ponds constructed and rehabilitated 230000 75000 ! Coord. 110000 Mawlamyinegyun 3,800 ! ! 160000 Env. Bogale Pyapon 0 Household latrines constructed ! Labutta 240000 Source: Office of the Resident Coordinator, Dec. 2009 67,430 190000 286000 • US $691 million has been requested in the Post-Nargis Households receiving agriculture support Recovery and Preparedness Plan (PONREPP) covering 12500 D D D D D D D D D D 344,112 11000 11000 2009-2011 Darfur Work P 2008 7000 • In 2009, US$132.8 million was received from a requirement Boats distributed 107000 0 20 40 80 6100 17000 of $247.3 million 25,029 5700 Kilometers 3900 2010 Priorities 11000 Ð 3700 5000 Ï Persons with disabilities provided with physical therapy Affected Population 160001 - 286000 23000 1700 An estimated 150,000 households are in urgent need 11,000 75001 - 160000 23001 - 75000 55000 of shelter assistance 12501 - 23000 Source : Humanitarian Country Team 1500 - 12500 156000 Need for construction of schools, provision of supplies, Affected Population in Township written in centre of The humanitarian community in Myanmar has worked tirelessly Produced 28 April 2009 Circle. -

Cyclone Nargis: What Are the Lessons from the 2004 Tsunami for Myanmar’S Recovery?

Risk, Livelihoods and Vulnerability Programme - May 2008 Cyclone Nargis: What are the Lessons from the 2004 Tsunami for Myanmar’s Recovery? FRANK THOMALLA, MATTHEW CHADWICK, SABRINA SHAW AND FIONA MILLER* n 2nd May 2008 Cyclone Nargis caused catastrophic relevant lessons are there for Myanmar? And looking forward, Odestruction and resulted in the deaths of nearly 80,000 how are immediate responses to disasters best designed to be in people in Myanmar. In the wake of one of the deadliest natural balance with longer term recovery? disasters in the country’s recent history, nearly 56,000 people are still missing, over 1 million are homeless and as many as 2.4 First, there is a need for coordinated collective action. million remain affected. The magnitude of the impacts of this A seemingly obvious point but challenging principle to tropical storm on an already impoverished country have been realise. During the 2004 Tsunami, many organisations were compared to those experienced by Sri Lanka, Indonesia and keen to respond and were under severe pressure to rapidly Thailand as a result of the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, as well as and transparently distribute considerable amounts of money to the devastation wrought by the 1991 cyclone in Bangladesh. pledged by the public, and to realise specific donor goals that sometimes diverged from needs on the ground. A First and foremost, it is of vital importance that sufficient lack of collective action, and at times blatant competition humanitarian assistance is allowed into the country to ensure the between agencies delivering humanitarian and livelihood survival of millions of affected people in the disaster zones. -

Manual on Cyclone

Scope of the Manual This manual is developed with wider consultations and inputs from various relevant departments/ministries, UN Agencies, INGOs, Local NGOs, Professional organizations including some independent experts in specific hazards. This is intended to give basic information on WHY, HOW, WHAT of a disaster. It also has information on necessary measures to be taken in case of a particular disaster in pre, during and post disaster scenario, along with suggested mitigation measures. It is expected that this will be used for the school teachers, students, parents, NGOs, Civil Society Organizations, and practitioners in the field of Disaster Risk Reduction. Excerpts from the speech of Ban Ki-moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations Don’t Wait for Disaster No country can afford to ignore the lessons of the earthquakes in Chile and Haiti. We cannot stop such disasters from happening. But we can dramatically reduce their impact, if the right disaster risk reduction measures are taken in advance. A week ago I visited Chile’s earthquake zone and saw how countless lives were saved because Chile’s leaders had learned the lessons of the past and heeded the warnings of crises to come. Because stringent earthquake building codes were enforced, much worse casualties were prevented. Training and equipping first responders ahead of time meant help was there within minutes of the tremor. Embracing the spirit that governments have a responsibility for future challenges as well as current ones did more to prevent human casualties than any relief effort could. Deaths were in the hundreds in Chile, despite the magnitude of the earthquake, at 8.8 on the Richter Scale, the fifth largest since records began. -

(ICT) Based Systems Can Contribute to Reducing Pollutant

27.11.2009 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 286 E/49 Thursday 19 June 2008 26. Recalls that information and communication technology (ICT) based systems can contribute to reducing pollutant emissions through more efficient traffic management, reduced fuel consumption and by facilitating eco-driving; 27. Invites the Commission to develop methodology for measuring the impact of ICTs on CO 2 emissions or to coordinate and disseminate existing findings; 28. Notes that the use and availability of portable or nomadic ICT-based device systems has increased and that the market for said devices continues to grow steadily; 29. Calls on stakeholders to work on measures to ensure the safe use and fixing of such devices, and to facilitate human-machine interaction; 30. Recalls that data privacy should be properly addressed and looks forward to the publication of the eSafety Forum's forthcoming data privacy code of practice; 31. Stresses the need for a definition by the European Telecommunications Standardisation Institute of an open standard for introducing eCall services at European level; 32. Welcomes the negotiations on the voluntary agreement on the inclusion of eCall as a standard option in all new vehicles from 2010 onwards; 33. Welcomes the negotiations on an international agreement for a global technical regulation which would include the technical specifications for the electronic stability control system, and calls on the Commission to draw up a report on the state of those negotiations and the measures agreed on the matter; 34. Looks forward to future reports on the development of the Safer, Cleaner, Efficient and Intelligent Car Initiative; 35. -

Impacts and Responses

Impacts and responses This information has been summarised from the Introduction to Tropical Meteorology (2nd Edition) which can be accessed, free of charge, on the MetEd/ COMET website (requires free registration). Introduction Tropical cyclones are the most hazardous tropical weather systems. Their hazards include: . strong winds . storm surge . wind-driven waves . heavy rainfall & flooding . tornadoes . lightning Their Impacts fall into two categories: . Direct impacts result directly from the storm itself, and include coastal erosion by storm surge and loss of infrastructure from wind stress. Indirect impacts occur as a consequence of direct impacts, and include diseases associated with water contamination, oil price increases when drilling platforms and refineries are damaged or closed, and fires started by live, downed power lines. Furthermore, some indirect impacts are longer term, including economic loss from damage to crops and fisheries where livelihoods are dependent on agriculture, post disaster stress, and insurance rate increases. The hazards created by tropical cyclones have a variety of impacts that vary spatially and temporally. Societal and Environmental Impacts Storm Surge and Wind-driven Waves Whenever there was a large loss of life from tropical cyclones, the predominant cause of death was drowning, not wind or windblown objects or structural failures. Globally, storm surge is the deadliest direct TC hazard. A storm surge is a large dome of water, 50 to 100 miles wide, that sweeps across the coast near where a hurricane makes landfall. It can be more than 5 metres deep at its peak (Fig. 1). Figure 1 A conceptual model of storm surge. NOAA The storm surge is created by wind-driven waves resulting from the low-pressure at the centre of the cyclone. -

Fact Sheet: USAID Assistance to Burma from 2008

USAID Assistance to Burma from 2008 - 2012 USAID has been providing humanitarian assistance to Burma since 2000. In 2008, our efforts scaled up in response to the devastation of Cyclone Nargis. From 2008 to 2012, the United States has provided a total of $196 million in bilateral foreign assistance funding to support humanitarian needs, promote democracy, and human rights through projects focused on civil society capacity building, health, education, and humanitarian assistance along the Thai-Burma border, in the Irrawaddy delta, and in central Burma. Civil Society USAID assistance has strengthened civil society within Burma and among internally displaced persons (IDP) and refugee communities on the Thai-Burma border through the delivery of health, education, emergency assistance, institutional capacity building, media, advocacy, and migrant protection activities. This work has built a strong foundation for new democracy programs to promote future citizen-led advances in the reform process underway. For example, within seven provinces in Thailand and six states in eastern Burma, 105 community- based organizations (CBOs) and local NGOs have participated in managerial and technical training. USAID has established four resource centers that continue to provide ongoing capacity building support for CBOs and NGOs. Within central Burma, USAID has established and support 372 democratically elected village development committees, 453 health development funds, 892 mother groups, 575 income generation organizations, and 156 water and sanitation groups. USAID’s civil society strengthening program has increased the capacity of CBOs focusing on child protection, created opportunities for parents and caregivers to participate in local decision-making processes, and built informal networks of teachers working in non-state, community-based schools.