Pages 391–412

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Additional Information

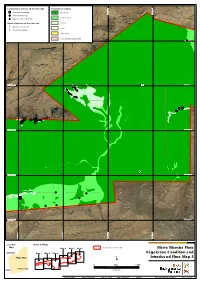

Current Survey Introduced Flora Records Vegetation Condition *Acetosa vesicaria Excellent 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 -

Seed Ecology Iii

SEED ECOLOGY III The Third International Society for Seed Science Meeting on Seeds and the Environment “Seeds and Change” Conference Proceedings June 20 to June 24, 2010 Salt Lake City, Utah, USA Editors: R. Pendleton, S. Meyer, B. Schultz Proceedings of the Seed Ecology III Conference Preface Extended abstracts included in this proceedings will be made available online. Enquiries and requests for hardcopies of this volume should be sent to: Dr. Rosemary Pendleton USFS Rocky Mountain Research Station Albuquerque Forestry Sciences Laboratory 333 Broadway SE Suite 115 Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA 87102-3497 The extended abstracts in this proceedings were edited for clarity. Seed Ecology III logo designed by Bitsy Schultz. i June 2010, Salt Lake City, Utah Proceedings of the Seed Ecology III Conference Table of Contents Germination Ecology of Dry Sandy Grassland Species along a pH-Gradient Simulated by Different Aluminium Concentrations.....................................................................................................................1 M Abedi, M Bartelheimer, Ralph Krall and Peter Poschlod Induction and Release of Secondary Dormancy under Field Conditions in Bromus tectorum.......................2 PS Allen, SE Meyer, and K Foote Seedling Production for Purposes of Biodiversity Restoration in the Brazilian Cerrado Region Can Be Greatly Enhanced by Seed Pretreatments Derived from Seed Technology......................................................4 S Anese, GCM Soares, ACB Matos, DAB Pinto, EAA da Silva, and HWM Hilhorst -

Transline Infrastructure Corridor Vegetation and Flora Survey

TROPICANA GOLD PROJECT Tropicana – Transline Infrastructure Corridor Vegetation and Flora Survey 025 Wellington Street WEST PERTH WA 6005 phone: 9322 1944 fax: 9322 1599 ACN 088 821 425 ABN 63 088 821 425 www.ecologia.com.au Tropicana Gold Project Tropicana Joint Venture Tropicana-Transline Infrastructure Corridor: Vegetation and Flora Survey July 2009 Tropicana Gold Project Tropicana-Transline Infrastructure Corridor Flora and Vegetation Survey © ecologia Environment (2009). Reproduction of this report in whole or in part by electronic, mechanical or chemical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, in any language, is strictly prohibited without the express approval of ecologia Environment and/or AngloGold Ashanti Australia. Restrictions on Use This report has been prepared specifically for AngloGold Ashanti Australia. Neither the report nor its contents may be referred to or quoted in any statement, study, report, application, prospectus, loan, or other agreement document, without the express approval of ecologia Environment and/or AngloGold Ashanti Australia. ecologia Environment 1025 Wellington St West Perth WA 6005 Ph: 08 9322 1944 Fax: 08 9322 1599 Email: [email protected] i Tropicana Gold Project Tropicana-Transline Infrastructure Corridor Flora and Vegetation Survey Executive Summary The Tropicana JV (TJV) is currently undertaking pre-feasibility studies on the viability of establishing the Tropicana Gold Project (TGP), which is centred on the Tropicana and Havana gold prospects. The proposed TGP is located approximately 330 km east north-east of Kalgoorlie, and 15 km west of the Plumridge Lakes Nature Reserve, on the western edge of the Great Victoria Desert (GVD) biogeographic region of Western Australia. -

RESPONSE to OEPA SUBMISSIONS Please Note That All Tables and Figures Are Presented at the Back of the Main Table

RESPONSE TO OEPA SUBMISSIONS Please note that all tables and figures are presented at the back of the main table OEPA Comment Proponent Response 1 OEPA Response to Proponent Response Proponent Response 2 Flora and Vegetation Please provide additional detail regarding As outlined in the Haul Road Management Lost Sands response does not provide any Although a precise quantification of infrastructure impacts cannot be provided to the completion of the management, monitoring and Plan Section 4.3.2 the indirect potential attempt to quantify the indirect impacts to Flora detailed road design, the following section provides a broad estimate and assessment of indirect mitigation of indirect impacts to Flora and impacts to flora and vegetation from the and Vegetation. For example, no modelling of impacts of the construction and operations of the haul road within the GVDNR. The proposed haul road Vegetation as a result of the construction Project include: dust had been attempted to demonstrate how will be the only infrastructure within the GVDNR. The estimation of indirect impacts includes additional and operation of the haul road. Where modification of surface and many hectares of vegetation within the GVDRN modelling activities related to indirect impacts of dust and hydrological processes on the GVDNR. possible indirect impacts should be groundwater flows (surface would be impacted by dust deposition during quantified. Indirect impacts which should the operations of the haul road. No justification hydrology and erosion); Indirect impacts resulting from the generation of Dust from the Haul Road be addressed in the Response to has been provided as to why this comment has introduction and spread of weeds; Submissions include the following: not been addressed. -

May Plant Availability List

May 2021: Plants Available—While They Last! Plants listed below are available to purchase at Norrie's Gift & Garden Shop, currently open Wednesday–Sundays 11:00 am-2:00 pm. New plants are delivered each week. Please wear a mask and be mindful of physical distancing. Arboretum members receive 10% off on plants and other items not already discounted; Many plants are also available to buy online (shopucscarboretum.com) and pick up at Norrie's by appointment; Thank you for supporting the Arboretum! AUSTRALIAN PLANTS Acacia myrtifolia Darwinia citriodora 'Seaspray' Hakea salicifolia ‘Gold Medal’ Actinodium cunninghamii Darwinia leiostyla 'Mt Trio' Hakea scoparia Adenanthos cuneatus 'Coral Drift' Dendrobium kingianum Hardenbergia violacea 'Mini Haha' Adenanthos dobsonii Dodonaea adenophora Hardenbergia violacea 'White Out' Adenanthos sericeus subsp. sericeus Eremaea hadra Hibbertia truncata Adenanthos x cunninghamii Eremophila subteretifolia Hypocalymma cordfolium 'Golden Veil' Agonis flexuosa 'Jervis Bay Afterdark' Feijoa sellowiana Isopogon anemonifolius 'Mt. Wilson' Banksia 'Giant Candles' Gastrolobium celsianum Isopogon formosus Banksia integrifolia Gastrolobium minus Kennedia nigricans Banksia integifolia 'Roller Coaster' Gastrolobium praemorsum 'Bronze Butterfly' Kennedia prostrata Banksia marginata 'Minimarg' Gastrolobium truncatum Kunzea badjensis 'Badja Blush' Banksia occidentalis Grevillea 'Bonfire' Kunzea baxteri Banksia spinulosa 'Nimble Jack' Grevillea 'Canterbury Gold' Kunzea parvifolia Banksia spinulosa 'Red Rock' Grevillea ‘Cherry -

Eremophila Koobabbiensis (Scrophulariaceae), a New, Rare Species from the Wheatbelt of Western Australia

R.J.Nuytsia Chinnock 21(4): &157–162 A.B. Doley, (2011) Eremophila koobabbiensis (Scrophulariaceae), a new rare species 157 Eremophila koobabbiensis (Scrophulariaceae), a new, rare species from the wheatbelt of Western Australia Robert J.Chinnock1 and Alison B. Doley2 1State Herbarium of South Australia, Hackney Road, Adelaide, South Australia 5000 2‘Koobabbie’, Waddy Forest, Western Australia 6515 Email: [email protected] Abstract Chinnock, R.J. & Doley, A.B. Eremophila koobabbiensis (Scrophulariaceae), a new, rare species from the wheatbelt of Western Australia. Nuytsia 21(4): 157–162 (2011). Eremophila koobabbiensis Chinnock, sp.nov., is described and illustrated. This rare species is known only from one area north of Moora and its conservation is discussed. It is also established in cultivation and its long-term survival is assured. Introduction When the monograph of Eremophila and allied genera was published (Chinnock 2007) one of the authors of this paper (RJC) was aware of a number of undescribed species in Western Australia that had been seen in the field or had been isolated from existing herbarium collections but were either inadequate for the preparation of accounts for publication, or were discovered too late to be included in the monograph. Andrew Brown (Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia) also drew attention to other new species of which he was aware. Since the publication of the monograph, two new taxa, E. grandiflora A.P.Br. & B.Buirchell and E. densifolia F.Muell. subsp. erecta A.P.Br. & B.Buirchell have been published (Brown & Buirchell 2007). In this paper a new and rare species is described and illustrated. -

La Trobeana Is Kindly Sponsored by Mr Peter Lovell Lovell Chen Architects & Heritage Consultants

LAA TTROBEANAROBEANA Journal of the C. J. La Trobe Society Inc. Journal ofVol.11, the No.C. J. 3, LaNovember Trobe 2012Society Inc. ISSN 1447-4026 Vol. 6, No. 2, June 2007 ISSN 1447-4026 La Trobeana is kindly sponsored by Mr Peter Lovell LOVEll CHEN ARCHITECTS & HERITAGE CONSULTANTS Lovell Chen Pty Ltd, Level 5, 176 Wellington Pde, East Melbourne 3002, Australia Tel: +61 (0)3 9667 0800 Fax: +61 (0)3 9416 1818 Email [email protected] ABN 20 005 803 494 Contents 4 Introduction 37 Jane Wilson A Word from the President Research Report: Charles La Trobe’s contribution to the establishment of the 5 Adrienne E. Clarke Horticultural Gardens at Burnley A Message from the Chancellor of La Trobe University 39 Susan Priestley Crises of 1852 for Lieutenant-Governor Tributes La Trobe, Captain William Dugdale and La Trobeana Henrietta Augusta Davies Journal of the C J La Trobe Society Inc. Dr Brian La Trobe Vol. 11, No 3, November 2012. 6 Tim Gatehouse 46 Dr Jean McCaughey The Turkish La Trobe: The career of ISSN 1447-4026 7 Claude Alexandre de Bonneval, the Editorial Committee 8 Mr Bruce Nixon Sultan’s advisor at the Ottoman Court Loreen Chambers (Hon Editor) Helen Armstrong Articles 54 Roz Greenwood Dianne Reilly Book Review: The French Closet by Robyn Riddett 9 R.W. Home Alison Anderson Burgess La Trobe’s ‘honest looking German’: Designed by Ferdinand Mueller and the botanical Reports and Notices Michael Owen [email protected] exploration of gold-rush Victoria Helen Botham For contributions and subscriptions enquiries contact: 56 Anna Murphy Anniversary of the Death of The Honorary Secretary: Dr Dianne Reilly AM 17 The C. -

Newsletter No

Newsletter No. 167 June 2016 Price: $5.00 AUSTRALASIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY SOCIETY INCORPORATED Council President Vice President Darren Crayn Daniel Murphy Australian Tropical Herbarium (ATH) Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria James Cook University, Cairns Campus Birdwood Avenue PO Box 6811, Cairns Qld 4870 Melbourne, Vic. 3004 Australia Australia Tel: (+61)/(0)7 4232 1859 Tel: (+61)/(0) 3 9252 2377 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Secretary Treasurer Leon Perrie John Clarkson Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service PO Box 467, Wellington 6011 PO Box 975, Atherton Qld 4883 New Zealand Australia Tel: (+64)/(0) 4 381 7261 Tel: (+61)/(0) 7 4091 8170 Email: [email protected] Mobile: (+61)/(0) 437 732 487 Councillor Email: [email protected] Jennifer Tate Councillor Institute of Fundamental Sciences Mike Bayly Massey University School of Botany Private Bag 11222, Palmerston North 4442 University of Melbourne, Vic. 3010 New Zealand Australia Tel: (+64)/(0) 6 356- 099 ext. 84718 Tel: (+61)/(0) 3 8344 5055 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Other constitutional bodies Hansjörg Eichler Research Committee Affiliate Society David Glenny Papua New Guinea Botanical Society Sarah Matthews Heidi Meudt Advisory Standing Committees Joanne Birch Financial Katharina Schulte Patrick Brownsey Murray Henwood David Cantrill Chair: Dan Murphy, Vice President Bob Hill Grant application closing dates Ad hoc adviser to Committee: Bruce Evans Hansjörg Eichler Research -

DRAFT 25/10/90; Plant List Updated Oct. 1992; Notes Added June 2021

DRAFT 25/10/90; plant list updated Oct. 1992; notes added June 2021. PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE CONSERVATION VALUES OF OPEN COUNTRY PADDOCK, BOOLARDY STATION Allan H. Burbidge and J.K. Rolfe INTRODUCTION Boolardy Station is situated about 150 km north of Yalgoo and 140 km west-north-west of Cue, in the Shire of Murchison, Western Australia. Open Country Paddock (about 16 000 ha) is in the south-east corner of the station, at 27o05'S, 116o50'E. The most prominent named feature is Coolamooka Hill, near the eastern boundary of the paddock. There are no conservation reserves in this region, although there are some small reserves set aside for various other purposes. Previous biological data for the station consist of broad scale vegetation mapping and land system mapping. Beard (1976) mapped the entire Murchison region at 1: 1 000 000. The Open Country Paddock area was mapped as supporting mulga woodlands and shrublands. More detailed mapping of land system units for rangeland assessment purposes has been carried out more recently at a scale of 1: 40 000 (Payne and Curry in prep.). Seven land systems were identified in open Country Paddock (Fig. 1). Apart from these studies, no detailed biological survey work appears to have been done in the area. Open Country Paddock has been only lightly grazed by domestic stock because of the presence of Kite-leaf Poison (Gastrolobium laytonii) and a lack of fresh water. Because of this and the generally good condition of the paddock and presence of a wide range of plant species, P.J. -

Enabling the Market: Incentives for Biodiversity in the Rangelands

Enabling the Market: Incentives for Biodiversity in the Rangelands: Report to the Australian Government Department of the Environment and Water Resources by the Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre Anita Smyth Anthea Coggan Famiza Yunus Russell Gorddard Stuart Whitten Jocelyn Davies Nic Gambold Jo Maloney Rodney Edwards Rob Brandle Mike Fleming John Read June 2007 Copyright and Disclaimers © Commonwealth of Australia 2007 Information contained in this publication may be copied or reproduced for study, research, information or educational purposes, subject to inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment and Water Resources. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Australian Government does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Contributing author information Anita Smyth: CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems Anthea Coggan: CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems Famiza Yunus: CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems Russell Gorddard: CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems Stuart Whitten: CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems Jocelyn Davies: CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems Nic Gambold: Central Land Council Jo Maloney Rodney Edwards: Ngaanyatjarra Council Rob Brandle: South Austalia Department for Environment and Heritage Mike Fleming: South Australia Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation John Read: BHP Billiton Desert Knowledge CRC Report Number 18 Information contained in this publication may be copied or reproduced for study, research, information or educational purposes, subject to inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source. -

Genera in Myrtaceae Family

Genera in Myrtaceae Family Genera in Myrtaceae Ref: http://data.kew.org/vpfg1992/vascplnt.html R. K. Brummitt 1992. Vascular Plant Families and Genera, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew REF: Australian – APC http://www.anbg.gov.au/chah/apc/index.html & APNI http://www.anbg.gov.au/cgi-bin/apni Some of these genera are not native but naturalised Tasmanian taxa can be found at the Census: http://tmag.tas.gov.au/index.aspx?base=1273 Future reference: http://tmag.tas.gov.au/floratasmania [Myrtaceae is being edited at mo] Acca O.Berg Euryomyrtus Schaur Osbornia F.Muell. Accara Landrum Feijoa O.Berg Paragonis J.R.Wheeler & N.G.Marchant Acmena DC. [= Syzigium] Gomidesia O.Berg Paramyrciaria Kausel Acmenosperma Kausel [= Syzigium] Gossia N.Snow & Guymer Pericalymma (Endl.) Endl. Actinodium Schauer Heteropyxis Harv. Petraeomyrtus Craven Agonis (DC.) Sweet Hexachlamys O.Berg Phymatocarpus F.Muell. Allosyncarpia S.T.Blake Homalocalyx F.Muell. Pileanthus Labill. Amomyrtella Kausel Homalospermum Schauer Pilidiostigma Burret Amomyrtus (Burret) D.Legrand & Kausel [=Leptospermum] Piliocalyx Brongn. & Gris Angasomyrtus Trudgen & Keighery Homoranthus A.Cunn. ex Schauer Pimenta Lindl. Angophora Cav. Hottea Urb. Pleurocalyptus Brongn. & Gris Archirhodomyrtus (Nied.) Burret Hypocalymma (Endl.) Endl. Plinia L. Arillastrum Pancher ex Baill. Kania Schltr. Pseudanamomis Kausel Astartea DC. Kardomia Peter G. Wilson Psidium L. [naturalised] Asteromyrtus Schauer Kjellbergiodendron Burret Psiloxylon Thouars ex Tul. Austromyrtus (Nied.) Burret Kunzea Rchb. Purpureostemon Gugerli Babingtonia Lindl. Lamarchea Gaudich. Regelia Schauer Backhousia Hook. & Harv. Legrandia Kausel Rhodamnia Jack Baeckea L. Lenwebia N.Snow & ZGuymer Rhodomyrtus (DC.) Rchb. Balaustion Hook. Leptospermum J.R.Forst. & G.Forst. Rinzia Schauer Barongia Peter G.Wilson & B.Hyland Lindsayomyrtus B.Hyland & Steenis Ristantia Peter G.Wilson & J.T.Waterh. -

Sites of Botanical Significance Vol1 Part1

Plant Species and Sites of Botanical Significance in the Southern Bioregions of the Northern Territory Volume 1: Significant Vascular Plants Part 1: Species of Significance Prepared By Matthew White, David Albrecht, Angus Duguid, Peter Latz & Mary Hamilton for the Arid Lands Environment Centre Plant Species and Sites of Botanical Significance in the Southern Bioregions of the Northern Territory Volume 1: Significant Vascular Plants Part 1: Species of Significance Matthew White 1 David Albrecht 2 Angus Duguid 2 Peter Latz 3 Mary Hamilton4 1. Consultant to the Arid Lands Environment Centre 2. Parks & Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory 3. Parks & Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory (retired) 4. Independent Contractor Arid Lands Environment Centre P.O. Box 2796, Alice Springs 0871 Ph: (08) 89522497; Fax (08) 89532988 December, 2000 ISBN 0 7245 27842 This report resulted from two projects: “Rare, restricted and threatened plants of the arid lands (D95/596)”; and “Identification of off-park waterholes and rare plants of central Australia (D95/597)”. These projects were carried out with the assistance of funds made available by the Commonwealth of Australia under the National Estate Grants Program. This volume should be cited as: White,M., Albrecht,D., Duguid,A., Latz,P., and Hamilton,M. (2000). Plant species and sites of botanical significance in the southern bioregions of the Northern Territory; volume 1: significant vascular plants. A report to the Australian Heritage Commission from the Arid Lands Environment Centre. Alice Springs, Northern Territory of Australia. Front cover photograph: Eremophila A90760 Arookara Range, by David Albrecht. Forward from the Convenor of the Arid Lands Environment Centre The Arid Lands Environment Centre is pleased to present this report on the current understanding of the status of rare and threatened plants in the southern NT, and a description of sites significant to their conservation, including waterholes.