Ancient-World-Wide-System-Preview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nearest Stars: a Guided Tour by Sherwood Harrington, Astronomical Society of the Pacific

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 5 - Spring 1986 © 1986, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. The Nearest Stars: A Guided Tour by Sherwood Harrington, Astronomical Society of the Pacific A tour through our stellar neighborhood As evening twilight fades during April and early May, a brilliant, blue-white star can be seen low in the sky toward the southwest. That star is called Sirius, and it is the brightest star in Earth's nighttime sky. Sirius looks so bright in part because it is a relatively powerful light producer; if our Sun were suddenly replaced by Sirius, our daylight on Earth would be more than 20 times as bright as it is now! But the other reason Sirius is so brilliant in our nighttime sky is that it is so close; Sirius is the nearest neighbor star to the Sun that can be seen with the unaided eye from the Northern Hemisphere. "Close'' in the interstellar realm, though, is a very relative term. If you were to model the Sun as a basketball, then our planet Earth would be about the size of an apple seed 30 yards away from it — and even the nearest other star (alpha Centauri, visible from the Southern Hemisphere) would be 6,000 miles away. Distances among the stars are so large that it is helpful to express them using the light-year — the distance light travels in one year — as a measuring unit. In this way of expressing distances, alpha Centauri is about four light-years away, and Sirius is about eight and a half light- years distant. -

Stellar Distances Teacher Guide

Stars and Planets 1 TEACHER GUIDE Stellar Distances Our Star, the Sun In this Exploration, find out: ! How do the distances of stars compare to our scale model solar system?. ! What is a light year? ! How long would it take to reach the nearest star to our solar system? (Image Credit: NASA/Transition Region & Coronal Explorer) Note: The above image of the Sun is an X -ray view rather than a visible light image. Stellar Distances Teacher Guide In this exercise students will plan a scale model to explore the distances between stars, focusing on Alpha Centauri, the system of stars nearest to the Sun. This activity builds upon the activity Sizes of Stars, which should be done first, and upon the Scale in the Solar System activity, which is strongly recommended as a prerequisite. Stellar Distances is a math activity as well as a science activity. Necessary Prerequisite: Sizes of Stars activity Recommended Prerequisite: Scale Model Solar System activity Grade Level: 6-8 Curriculum Standards: The Stellar Distances lesson is matched to: ! National Science and Math Education Content Standards for grades 5-8. ! National Math Standards 5-8 ! Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (grades 6 and 8) ! Content Standards for California Public Schools (grade 8) Time Frame: The activity should take approximately 45 minutes to 1 hour to complete, including short introductions and follow-ups. Purpose: To aid students in understanding the distances between stars, how those distances compare with the sizes of stars, and the distances between objects in our own solar system. © 2007 Dr Mary Urquhart, University of Texas at Dallas Stars and Planets 2 TEACHER GUIDE Stellar Distances Key Concepts: o Distances between stars are immense compared with the sizes of stars. -

Planets and Exoplanets

NASE Publications Planets and exoplanets Planets and exoplanets Rosa M. Ros, Hans Deeg International Astronomical Union, Technical University of Catalonia (Spain), Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias and University of La Laguna (Spain) Summary This workshop provides a series of activities to compare the many observed properties (such as size, distances, orbital speeds and escape velocities) of the planets in our Solar System. Each section provides context to various planetary data tables by providing demonstrations or calculations to contrast the properties of the planets, giving the students a concrete sense for what the data mean. At present, several methods are used to find exoplanets, more or less indirectly. It has been possible to detect nearly 4000 planets, and about 500 systems with multiple planets. Objetives - Understand what the numerical values in the Solar Sytem summary data table mean. - Understand the main characteristics of extrasolar planetary systems by comparing their properties to the orbital system of Jupiter and its Galilean satellites. The Solar System By creating scale models of the Solar System, the students will compare the different planetary parameters. To perform these activities, we will use the data in Table 1. Planets Diameter (km) Distance to Sun (km) Sun 1 392 000 Mercury 4 878 57.9 106 Venus 12 180 108.3 106 Earth 12 756 149.7 106 Marte 6 760 228.1 106 Jupiter 142 800 778.7 106 Saturn 120 000 1 430.1 106 Uranus 50 000 2 876.5 106 Neptune 49 000 4 506.6 106 Table 1: Data of the Solar System bodies In all cases, the main goal of the model is to make the data understandable. -

Exoplanet Atmosphere Measurements from Direct Imaging

Exoplanet Atmosphere Measurements from Direct Imaging Beth A. Biller and Mickael¨ Bonnefoy Abstract In the last decade, about a dozen giant exoplanets have been directly im- aged in the IR as companions to young stars. With photometry and spectroscopy of these planets in hand from new extreme coronagraphic instruments such as SPHERE at VLT and GPI at Gemini, we are beginning to characterize and classify the at- mospheres of these objects. Initially, it was assumed that young planets would be similar to field brown dwarfs, more massive objects that nonetheless share sim- ilar effective temperatures and compositions. Surprisingly, young planets appear considerably redder than field brown dwarfs, likely a result of their low surface gravities and indicating much different atmospheric structures. Preliminarily, young free-floating planets appear to be as or more variable than field brown dwarfs, due to rotational modulation of inhomogeneous surface features. Eventually, such inho- mogeneity will allow the top of atmosphere structure of these objects to be mapped via Doppler imaging on extremely large telescopes. Direct imaging spectroscopy of giant exoplanets now is a prelude for the study of habitable zone planets. Even- tual direct imaging spectroscopy of a large sample of habitable zone planets with future telescopes such as LUVOIR will be necessary to identify multiple biosigna- tures and establish habitability for Earth-mass exoplanets in the habitable zones of nearby stars. Introduction Since 1995, more than 3000 exoplanets have been discovered, mostly via indirect means, ushering in a completely new field of astronomy. In the last decade, about a dozen planets have been directly imaged, including archetypical systems such as arXiv:1807.05136v1 [astro-ph.EP] 13 Jul 2018 Beth A. -

The Milky Way the Milky Way's Neighbourhood

The Milky Way What Is The Milky Way Galaxy? The.Milky.Way.is.the.galaxy.we.live.in..It.contains.the.Sun.and.at.least.one.hundred.billion.other.stars..Some.modern. measurements.suggest.there.may.be.up.to.500.billion.stars.in.the.galaxy..The.Milky.Way.also.contains.more.than.a.billion. solar.masses’.worth.of.free-floating.clouds.of.interstellar.gas.sprinkled.with.dust,.and.several.hundred.star.clusters.that. contain.anywhere.from.a.few.hundred.to.a.few.million.stars.each. What Kind Of Galaxy Is The Milky Way? Figuring.out.the.shape.of.the.Milky.Way.is,.for.us,.somewhat.like.a.fish.trying.to.figure.out.the.shape.of.the.ocean.. Based.on.careful.observations.and.calculations,.though,.it.appears.that.the.Milky.Way.is.a.barred.spiral.galaxy,.probably. classified.as.a.SBb.or.SBc.on.the.Hubble.tuning.fork.diagram. Where Is The Milky Way In Our Universe’! The.Milky.Way.sits.on.the.outskirts.of.the.Virgo.supercluster..(The.centre.of.the.Virgo.cluster,.the.largest.concentrated. collection.of.matter.in.the.supercluster,.is.about.50.million.light-years.away.).In.a.larger.sense,.the.Milky.Way.is.at.the. centre.of.the.observable.universe..This.is.of.course.nothing.special,.since,.on.the.largest.size.scales,.every.point.in.space. is.expanding.away.from.every.other.point;.every.object.in.the.cosmos.is.at.the.centre.of.its.own.observable.universe.. Within The Milky Way Galaxy, Where Is Earth Located’? Earth.orbits.the.Sun,.which.is.situated.in.the.Orion.Arm,.one.of.the.Milky.Way’s.66.spiral.arms..(Even.though.the.spiral. -

Are We Going to Alpha Centauri?

REVIEW https://doi.org/10.32386/scivpro.000019 Are we going to Alpha Centauri? Didier Queloz, Mejd Alsari* Nobel Prize Laureate Didier Queloz talks about realistic ways to explore Proxima Centauri b and other potentially habitable planetary systems such as TRAPPIST-1 using technologies that are currently available. He also discusses his interdisciplinary research activities on abiogenesis and the search for life on other planets. See video at https://youtu.be/RODr30duRrg. Mejd Alsari (MA). Does the Drake Equation1,2 define a sort of roadmap for astronomers in their quest for understanding our uni- verse when you read it from left to right? Note: the Drake Equation predicts the number of extant advanced technical civilizations possessing both the interest and the capabili- * 1 ty for interstellar communication as N=R ×fp×ne×fl×fi×fc×L, where: • R* is the mean rate of star formation averaged over the lifetime of our Galaxy; • fp is the fraction of stars with planetary systems; • ne is the mean number of planets in each planetary system with environments favourable for the origin of life; • fl is the fraction of such favourable planets on which life de- velops; Figure 1 | Prof. Didier Queloz, Professor of Physics, Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge. • fi is the fraction of such inhabited planets on which intelligent life arises during the lifetime of the local star; • fc is the fraction of planets populated by intelligent beings on tested. It’s a chemistry experiment that needs to be done to address which an advanced technical civilization arises during the life- these fundamental questions. -

Report 2017 Research, Education and Public Outreach Activity Report 2017 Research, Education and Public Outreach

Activity Report 2017 Research, Education and Public Outreach Activity Report 2017 Research, Education and Public Outreach Nathalie A. Cabrol Director, Carl Sagan Center, Pamela Harman, Acting Director, Center for Education Rebecca McDonald Director, Center for Outreach Bill Diamond President & CEO The SETI Institute: 189 N Bernardo Avenue Suite 200, Mountain View, CA 94043. Phone: (650) 961-6633 Activity Report 2017 Research, Education and Public Outreach TABLE OF CONTENTS Peer-reviewed publications 10 Conferences: Abstracts & Proceedings 18 Technical Reports & Data Releases 29 Outreach, Media Coverage, Web Stories & Interviews 31 Invited Talks (Professional & Public) 39 Highlights, Significant Events & Activities 46 Fieldwork 52 Honors & Awards 54 Missions, Observations & Strategic Planning 56 Acknowledgements 60 The SETI Institute: 189 N Bernardo Avenue Suite 200, Mountain View, CA 94043. Phone: (650) 961-6633 Activity Report 2017 Research, Education and Public Outreach FROM THE SETI INSTITUTE President and CEO Dear friends, The scientists, educators and outreach professionals of the SETI Institute had yet another banner year of productivity in 2017. We are delighted to present our 2nd annual report, cataloging the research and education programs of the Institute, as well as the myriad of mainstream media stories about our people and our work. Among the highlights from this year’s report are 147 peer-reviewed articles in scientific journals, 225 conference proceedings and abstracts, 172 media stories and interviews, and 177 invited talks. -

Alpha Centauri

8 www.Astronomy.com Thank you for registering on Astronomy.com! We hope you enjoy these two articles that provide you with just a small sample of what Astronomy magazine has to offer. Please remember that this copyrighted material is for your use only. It is unlawful to share or distribute this file to others in any way, including e-mailing it, posting it online, or sharing paper copies with others. If you have suggestions or comments on this product, please contact us at [email protected]. Sincerely, The staff of Astronomy magazine TROUBLESHOOTING GUIDE Please note: Packages are color intensive. To save color ink in your printer, change your printer setting to grayscale. SAVING PACKAGE Save the package when you download the PDF. Click on the computer disk icon in Adobe Acrobat, or go to File, Save. MY PRINTER WON’T PRINT THE TEXT CORRECTLY Close all other programs/applications and print directly out of the Acrobat Reader program, not your Web browser. Printing problems are caused by not enough free system memory. PAGES ARE NOT PRINTING FULL SIZE Set your printer to print 100% and make sure “print to fit” is not checked under printer setup or printer options. To boldly go ... How humans will travel to Alpha Centauri Long thought to be the province of science fiction, interstellar flight might not be as impossible as you think. by Bill Andrews pace, we all know, is the final frontier. But years ago. Starting just eight years later, a dozen men given our current technological state, it trod on the surface of another world, the Moon, for might stay that way for some time. -

Selected Studies of Orbital Stability and Habitability In

SELECTED STUDIES OF ORBITAL STABILITY AND HABITABILITY IN STAR-PLANET SYSTEMS by WILLIAM JASON EBERLE Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON December 2010 I dedicate this to my daughter Astra Chalisa Eberle. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervising professor Dr. Manfred Cuntz for constantly motivating and encouraging me, and also for his invaluable advice during the course of my studies. I wish to thank Dr. Zdzislaw Musielak, Dr. Ramon Lopez, Dr. Alex Weiss and Dr. Qiming Zhang for their interest in my research and for taking time to serve in my committee. I would also like to express my deep gratitude to my parents, Kip and Darlene Eberle, without whom I wouldn't even be alive. They have motivated me and made many sacrifices to provide me with opportunities that they didn't have. I am also extremely grateful to my wife Sarinya for her encouragement and patience. I also want to thank my sisters Sandy and Nikki for their perspectives that have helped to develop mine. Finally, I want to acknowledge all of my friends and acquaintances that I have known throughout my education especially Travis Collavo for his invaluable comments which improved this work. November 15, 2010 iii ABSTRACT SELECTED STUDIES OF ORBITAL STABILITY AND HABITABILITY IN STAR-PLANET SYSTEMS William Jason Eberle, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2010 Supervising Professor: Manfred Cuntz The study of planets remaining in orbit around one star with another star interfering is an important topic of orbital mechanics and astrobiology. -

Planet Detectability in the Alpha Centauri System

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Institucional Académico Universidad Andrés Bello The Astronomical Journal, 155:24 (12pp), 2018 January https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/aa9bea © 2017. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Planet Detectability in the Alpha Centauri System Lily Zhao1 , Debra A. Fischer1 , John Brewer1 , Matt Giguere1 , and Bárbara Rojas-Ayala2 1 Yale University, 52 Hillhouse, New Haven, CT 06511, USA; [email protected] 2 Departamento de Ciencias Físicas, Universidad Andrés Bello, Fernández Concha 700 Edificio C1 Piso 3, 7591538 Santiago, Chile Received 2017 July 1; revised 2017 November 14; accepted 2017 November 16; published 2017 December 18 Abstract We use more than a decade of radial-velocity measurements for a Cen A, B, and Proxima Centauri from the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher, CTIO High Resolution Spectrograph, and the Ultraviolet and Visual Echelle Spectrograph to identify the Misin and orbital periods of planets that could have been detected if they existed. At each point in a mass–period grid, we sample a simulated, Keplerian signal with the precision and cadence of existing data and assess the probability that the signal could have been produced by noise alone. Existing data places detection thresholds in the classically defined habitable zones at about Misin of 53 MÅ for a Cen A, 8.4 MÅ for a Cen B, and 0.47 MÅ for Proxima Centauri. Additionally, we examine the impact of systematic errors, or “red noise” in the data. A comparison of white- and red-noise simulations highlights quasi-periodic variability in the radial velocities that may be caused by systematic errors, photospheric velocity signals, or planetary signals. -

The Sky Tonight April

horse. Sources differ on which centaur the APRIL PAENGA-WHĀ WHĀ HIGHLIGHTS constellation represents, but most consider it to be Chiron, who mentored many Greek THE SKY TONIGHT heroes. Centaurus was one of the 48 - - - constellations described in the 2nd century TE AHUA O TE RAKI I TENEI PO by astronomer Ptolemy, and it remains one Omega Centauri of the 88 modern constellations. Originally thought to be a single star, in 1677, this fuzzy spot was identified to High in the southeast, you will find two be a cluster that actually contains around bright stars that appear close together, 10 million individual stars. Pictured on called Alpha Centauri and Beta Centauri. the cover, Omega Centauri is a globular These stars mark the two front legs of the cluster: a collection of stars that orbits a centaur, and also act as the pointer stars galactic core. This is the largest of these in to help find the Southern Cross. the Milky Way, with light taking 150 years to travel from one edge to the other. Omega Centauri has a mass four million times that of our Sun, making it also the Image: Johannes Hevelius – Wikimedia Commons most massive cluster in our galaxy. The light coming from the millions of stars in the cluster has travelled for 15 800 years to reach us here on Earth. As this cluster is most easily seen from April to September, now is the time to start looking for it. Brighter than any other star cluster, Omega Centauri can currently be found high in the southeastern sky, along the back of the constellation Centaurus. -

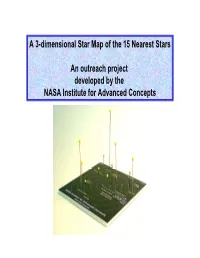

3-D Star Map of the 15 Nearest Stars

A 3-dimensional Star Map of the 15 Nearest Stars An outreach project developed by the NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts Star Map Base Top Bottom USRA HD 217987 ANSER Star Type Distance (lt-yrs) Sol G2V 0 Ross 248 UV Ceti A 10 light Proxima Centauri M5Ve 4.22 UV Ceti B years Alpha Centauri A G2V 4.39 8 Alpha Centauri B K1V 4.39 Epsilon Eridani 6 Barnard's Star sdM4 5.94 Wolf 359 M6.5Ve 7.8 4 Ross 154 Lalande 21185 M2V 8.31 2 Sirius A A0m 8.6 Barnard's Star Sirius B DA2 8.6 Sol UV Ceti A M5.5Ve 8.7 27,000 light years Sirius A UV Ceti B M5.5Ve 8.7 Proxima Centauri to the center of Sirius B Ross 154 M3.5Ve 9.69 our galaxy Alpha Centauri A Ross 248 M5.5Ve 10.3 Alpha Centauri B Epsilon Eridani K2V 10.5 HD 217987 M2/M3V 10.73 One inch equals 4 light years Lalande 21185 Wolf 359 The arrow from the Sun points toward the galactic center, the black surface is parallel to the galactic plane, and NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts the wires point “up” normal to the galactic plane. www.niac.usra.edu Star Map Base (White Background) Top Bottom USRAHD 217987 ANSER Star Type Distance (lt-yrs) Sol G2V 0 Ross 248 UV Ceti A 10 light Proxima Centauri M5Ve 4.22 UV Ceti B years Alpha Centauri A G2V 4.39 8 Alpha Centauri B K1V 4.39 Epsilon Eridani 6 Barnard's Star sdM4 5.94 Wolf 359 M6.5Ve 7.8 4 Ross 154 Lalande 21185 M2V 8.31 2 Sirius A A0m 8.6 Barnard's Star Sirius B DA2 8.6 Sol UV Ceti A M5.5Ve 8.7 27,000 light years Sirius A UV Ceti B M5.5Ve 8.7 Proxima Centauri to the center of Sirius B Ross 154 M3.5Ve 9.69 our galaxy Alpha Centauri A Ross 248 M5.5Ve 10.3 Alpha Centauri B Epsilon Eridani K2V 10.5 HD 217987 M2/M3V 10.73 One inch equals 4 light years Lalande 21185 Wolf 359 The arrow from the Sun points toward the galactic center, the white surface is parallel to the galactic plane, and NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts the wires point “up” normal to the galactic plane.