Inventário, N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grumpyʼs Noughties Quiz Questions & Tinfoil Challenge

Grumpyʼs Noughties Quiz Questions & Tinfoil Challenge 1. Which album sold more copies: James Blunt's "Back to Bedlam" or Amy Winehouse's "Back to Black"? 2. Who wrote the hit noughties novel "The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time"? 3. Russell Brand and Jonathan Ross were widely criticised in 2008 for leaving a rude message on whose answerphone? 4. Who was Britney Spears married to for only 55 hours in 2004? 5. Who resigned over the decision to go to war with Iraq in 2003 and received the first ever standing ovation in the House of Commons? 6. What is the name of napoleon dynamite’s llama? 7. Which country was the first to legalise same-sex marriage in 2001? Multiple Choice: A. The Netherlands / B. Belgium / C. Germany 8. Who is the main character in "The Da Vinci Code"? 9. What was George Bush doing when the September 11 attacks began in 2001? Mulitiple Choice: A.Shopping for shoes / B. Reading to schoolchildren / C. Playing golf 10. Which newspaper does "Sex and the City’s Carrie Bradshaw write a column for? 11. Who did Italy beat in the 2006 World Cup final? 12. On "Lost", the survivors of a plane crash are left on a desert island. What was their flight? Multiple Choice: A. Atlantic Airlines Flight 514 / B. Oceanic Airlines Flight 815 13. What was the name of the boyband who lost out to Girls Aloud on "Popstars: The Rivals"? 14. In 2002, how many rounds did it take Lennox Lewis KO Mike Tyson? 15. -

USED Cds ––– NEW ARRIVALS ––– December 19 2020

USED CDs ––– NEW ARRIVALS ––– December 19 2020 REFCODE ARTIST TITLE RRP 11614 3DS VENUS TRAIL 19.95 10222 3DS HELLZAPOPPIN 19.95 253673 ABBA NUMBER ONES (2CD) 17.95 276551 AEROSMITH GET YOUR WINGS (REMASTERED) 12.95 561408 ALEX THIS IS ME 12.95 489421 AMOROSI VANESSA POWER 12.95 253936 ARCADE FIRE NEON BIBLE 12.95 79597 BATS THOUSANDS OF TINY LUMINOUS SPHERES19.95 8398 BATS SILVERBEET 14.95 112205 BEE GEES RECORD - THEIR GREATEST HITS (2CD)15.95 404210 BEETHOVEN/ASHKENAZY PIANO CONCERTOS 3/4 12.95 19410 BELEW ADRIAN YOUNG LIONS 12.95 289056 BEYONCE I AM SASHA FIERCE (2CD) 14.95 205432 BJORK MUSIC FROM DRAWING RESTRAINT 9 12.95 368828 BJORK BIOPHILIA 12.95 11624 BJORK TELEGRAM 12.95 198139 BLUNT JAMES BACK TO BEDLAM 12.95 122936 BOARDS OF CANADA GEOGADDI (LTD EDITION PACKAGING)25.95 258886 BOWIE DAVID YOUNG AMERICANS (CD/DVD SPECIAL39.95 EDITION) 241519 BRAGG BILLY MUST I PAINT YOU A PICTURE (2CD) 17.95 363734 BRAHMS/ASHKENAZY PIANO CONCERTO NO 2 14.95 37771 CACOPHONY SPEED METAL SYMPHONY 17.95 231406 CASH JOHNNY AMERICAN 5 HUNDRED HIGHWAYS 12.95 8528 CHAPMAN TRACY TRACY CHAPMAN 12.95 109753 CHAPMAN TRACY COLLECTION 12.95 13025 CLASH SINGLES 12.95 73602 COLDPLAY PARACHUTES 12.95 171283 COLTRANE JOHN ASCENSION (DIGI) 15.95 561364 COPELAND GREG/MARTIN MESSINGDEEP DOWN SOUTH 15.95 561394 CORRS TALK ON CORNERS (AUTOGRAPHED)39.95 170526 COULTER/JAMES GALWAY LEGENDS 12.95 34005 CROSBY STILLS AND NASH CROSBY STILLS AND NASH (REMASTERED)12.95 114370 CULTURE CLUB BEST OF (BLACK COVER) 12.95 561407 D SIDE BEST OF D SIDE 2004-2209 (BONUS DVD)17.95 -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Dokumentation „Amy – the Girl Behind the Name”

Bemerkungen zur Dokumentation „Amy – The Girl behind the Name” Erscheinungsjahr: 2015 Regisseur: Asif Kapadia Mitwirkende: ANDREW MORRIS (Bodyguard), BLAKE FIELDER-CIVIL (Ex- Gatte), BLAKE WOOD (Freund), CHIP SOMERS (Drogenberater), DALE DAVIS (Musical Director & Bassist), DARCUS BEESE (A&R (jetzt Präsident), Island Records), DR. CRISTINA ROMETE (Ärztin), GUY MOOT ( Präsident, Sony/ATV Publishing), JANIS WINEHOUSE (Amys Mutter), JULIETTE ASHBY(Freundin), LAUREN GILBERT(Freundin), LUCIAN GRAINGE (Vorstand & CEO, Universal Music Group), MARK RONSON (Musikproduzent), MITCHEL WINEHOUSE (Amys Vater), MONTE LIPMAN (Vorsitzender & CEO, Republic Records), NICK GATFIELD (Präsident, Island Records 2001-08), NICK SHYMANSKY (Amys erster Manager), PETER DOHERTY (Musiker), PHIL MEYNELL (Freund), RAYE COSBERT (Amys Manager, Metropolis Musik), SALAAM REMI (Musikproduzent), SAM BESTE (Pianist), SHOMARI DILON (Tontechniker), TONY BENNETT (Sänger), TYLER JAMES (Freund), YASIIN BEY(Hip-Hop-Künstler) Vorbemerkungen: Amy Jade Winehouse (* 1983;† 2011) war eine britische Sängerin und Songschreiberin. Als große Vorbilder bezeichnete Amy immer die Jazz-Ikonen Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan und Tony Benett. Im Alter von 16 Jahren war sie kurze Zeit des National Youth Jazz Orchestra (NYJO) in England. Bill Ashton, der 1965 das National Youth Jazz Orchestra in England mit gegründet hatte, sagte zum Debut- Auftritt der Band mit Amy im Jahr 2000 wörtlich: “I can honestly say, she had the best jazz voice of any young singer I had ever heard”. Amy tourte ein halbes Jahr lang (vor ihrem Durchbruch als Soul-/Pop-Sängerin) mit zwei Mitgliedern des NYJO durch kleine englische Jazz-Clubs. Sie liebte die Atmosphäre in Jazz-Clubs mehr als große Konzerthallen. Bill Ashton sagte zum Tod von Amy: “…the pop world has lost an icon – the jazz world lost a great jazz singer several years ago”. -

De Classic Album Collection

DE CLASSIC ALBUM COLLECTION EDITIE 2013 Album 1 U2 ‐ The Joshua Tree 2 Michael Jackson ‐ Thriller 3 Dire Straits ‐ Brothers in arms 4 Bruce Springsteen ‐ Born in the USA 5 Fleetwood Mac ‐ Rumours 6 Bryan Adams ‐ Reckless 7 Pink Floyd ‐ Dark side of the moon 8 Eagles ‐ Hotel California 9 Adele ‐ 21 10 Beatles ‐ Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band 11 Prince ‐ Purple Rain 12 Paul Simon ‐ Graceland 13 Meat Loaf ‐ Bat out of hell 14 Coldplay ‐ A rush of blood to the head 15 U2 ‐ The unforgetable Fire 16 Queen ‐ A night at the opera 17 Madonna ‐ Like a prayer 18 Simple Minds ‐ New gold dream (81‐82‐83‐84) 19 Pink Floyd ‐ The wall 20 R.E.M. ‐ Automatic for the people 21 Rolling Stones ‐ Beggar's Banquet 22 Michael Jackson ‐ Bad 23 Police ‐ Outlandos d'Amour 24 Tina Turner ‐ Private dancer 25 Beatles ‐ Beatles (White album) 26 David Bowie ‐ Let's dance 27 Simply Red ‐ Picture Book 28 Nirvana ‐ Nevermind 29 Simon & Garfunkel ‐ Bridge over troubled water 30 Beach Boys ‐ Pet Sounds 31 George Michael ‐ Faith 32 Phil Collins ‐ Face Value 33 Bruce Springsteen ‐ Born to run 34 Fleetwood Mac ‐ Tango in the night 35 Prince ‐ Sign O'the times 36 Lou Reed ‐ Transformer 37 Simple Minds ‐ Once upon a time 38 U2 ‐ Achtung baby 39 Doors ‐ Doors 40 Clouseau ‐ Oker 41 Bruce Springsteen ‐ The River 42 Queen ‐ News of the world 43 Sting ‐ Nothing like the sun 44 Guns N Roses ‐ Appetite for destruction 45 David Bowie ‐ Heroes 46 Eurythmics ‐ Sweet dreams 47 Oasis ‐ What's the story morning glory 48 Dire Straits ‐ Love over gold 49 Stevie Wonder ‐ Songs in the key of life 50 Roxy Music ‐ Avalon 51 Lionel Richie ‐ Can't Slow Down 52 Supertramp ‐ Breakfast in America 53 Talking Heads ‐ Stop making sense (live) 54 Amy Winehouse ‐ Back to black 55 John Lennon ‐ Imagine 56 Whitney Houston ‐ Whitney 57 Elton John ‐ Goodbye Yellow Brick Road 58 Bon Jovi ‐ Slippery when wet 59 Neil Young ‐ Harvest 60 R.E.M. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 25/02/2020 Sing Online on 1000 Most Popular Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 25/02/2020 Sing online on www.karafun.com 1000 most popular songs TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born My Way - Frank Sinatra Dreams - Fleetwood Mac Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Dancing Queen - ABBA Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Let It Go - Idina Menzel Santeria - Sublime Don't Stop Believing - Journey Old Town Road (remix) - Lil Nas X EXPLICIT Turn The Page - Bob Seger Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Fly Me to the Moon - Frank Sinatra Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Your Man - Josh Turner Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Valerie - Amy Winehouse House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Creep - Radiohead EXPLICIT Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi Wannabe - Spice Girls Dance Monkey - Tones and I Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Beautiful Crazy - Luke Combs Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley My Girl - The Temptations Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Jackson - Johnny Cash Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker All Of Me - John Legend Truth Hurts - Lizzo EXPLICIT I Wanna Dance with Somebody - Whitney Houston These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Perfect - Ed Sheeran Your Song - Elton John Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Zombie - The Cranberries Into the Unknown - Frozen 2 Girl Crush - Little Big Town Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Crazy - Patsy Cline -

By Mark Ronson | Amy Winehouse the Zutons | Annenmaykantereit

Analyse von Musikaufnahmen (253082b) Dozent: Prof. Oliver Curdt Studiengang: Audiovisuelle Medien - Master (Externes Wahlpflichtfach) Semester: SoSe 2020 Hochschule der Medien Stuttgart, den 06.08.2020 Valerie By Mark Ronson | Amy Winehouse The Zutons | AnnenMayKantereit Vorgelegt von: Korinna Lorentz (Matrikel-Nr.: 39708; Studiengang: Crossmedia Publishing & Management) Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 2 The Zutons ................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Entstehunggeschichte von Valerie................................................................................................................................ 5 2.1 Analyse von Valerie (The Zutons 2006) .................................................................................................................... 6 3 Amy Winehouse ............................................................................................................................................ 7 3.1 Live at BBC Radio.................................................................................................................................................. 8 3.2 Mark Ronson feat. Amy Winehouse .......................................................................................................................... 8 4 AnnenMayKantereit .................................................................................................................................... -

Band Song-List

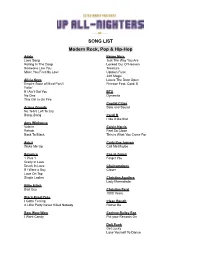

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

Billboard Magazine

WorldMags.net “Rehab” has been streamed more than 35 million times on Spotify — Winehouse herself is only dimly understood. “She never spent enough time [in the ONE DAY IN United States] for people to get a sense of her outside of being drunk and sloppy,” says Republic Records chairman/CEO Monte Lipman. David Joseph, chairman/ CEO of Universal Music U.K. and an NOVEMBER 2005, executive producer on Amy, says, “Some asked, ‘Are you making a film about a drug addict?’ People didn’t even realize she wrote her own lyrics.” The film is a riveting collage of audio interviews and mostly unseen footage. It AMY WINEHOUSE took the filmmakers two years to win the sat in a car with her friend and co-manager the screen they’ll feel embarrassed.” trust of Winehouse’s friends, many of whom Nick Shymansky, winding through the Like Britney Spears, another singer hadn’t spoken publicly since her death. “At English countryside toward a rehab center. classified as a “train wreck” at that time, the beginning nobody wanted to talk to me,” The singer’s drinking had been getting out Winehouse felt the lashes of 24-7 gossip says Kapadia. “Then everybody did.” Only of control, Shymansky remembers, and he coverage as it converged with her celebrity. Mitch Winehouse has since criticized the felt she needed help. When they arrived, And that wasn’t all Winehouse contended project, calling it “unbalanced.” Gay- Winehouse said she would check in on one with: The pressure to be thin worsened her Rees says that the initial three-hour cut condition: that her father, Mitch, agreed. -

Elenco Volumi Esposti Su Musica

COMUNE DI ALPIGNANO ASSESSORATO ALLA CULTURA In Biblioteca ... CD musica straniera pop-rock 1 Abba The album CD 782.42 ABB Bryan Adams So far so good CD 782.42 ADA Aerosmith Big Ones CD 782.42 AER Aerosmith Rockin' the joint CD 782.42 AER Christina Stripped CD 782.42 AGU Aguilera Air Moon safari CD 782.42 AIR The Alan I Robot CD 782.42 ALA Parsons Project America The definitive pop collection CD 782.42 AME Anastacia Anastacia CD 782.42 ANA Anastacia Pieces of a dream CD 782.42 ANA The Ark State of The Ark CD 782.42 ARK Richard Ashcroft Alone With Everybody CD 782.42 ASH Audioslave Out of exile CD 782.42 AUD Aventura God's project CD 782.42 AVE Backstreet Boys Millennium CD 782.42 BAC Backstreet Boys Backstreet's Back CD 782.42 BAC Joan Baez The Best of Joan C. Baez CD 782.42 BAE Basement Jaxx Kish kash CD 782.42 BAS B.B. King & Eric Riding With the King CD 782.42 BBK Clapton Beastie Boys Licensed to ill CD 782.42 BEA The Beatles The Beatles CD 782.42 BEA The Beatles The Beatles CD 782.42 BEA Beck Mutations CD 782.42 BEC George Benson The best of George Benson CD 782.42 BEN Samuele Bersani Che vita! CD 782.42 BER The B-52'S The B-52'S CD 782.42 BFI Björk SelmaSongs CD 782.42 BJO Björk Debut CD 782.42 BJO The Black Eyed Elephunk CD 782.42 BLA Peas The Black Eyed Monkey business CD 782.42 BLA Peas Blink-182 Blink-182 CD 782.42 BLI 2 Blur 13 CD 782.42 BLU Blues Brothers & Live from Chicago's house of blues CD 782.42 BLU Friends Blue Guilty CD 782.42 BLU Blue Best of Blue CD 782.42 BLU James Blunt Chasing time: the Bedlam sessions CD 782.42 BLU Michael Bolton Greatest Hits 1985-1995 CD 782.42 BOL Jon Bon Jovi Crush CD 782.42 BON David Bowie Live Santa Moica '72 CD 782.42 BOW Goran Bregovic Ederlezi CD 782.42 BRE James Brown Sex machine: The very best of James Brown CD 782.42 BRO Jackson Browne The Next Voice you Hear CD 782.42 BRO Michael Bublé It's time CD 782.42 BUB Jeff Buckley Sketches for my Sweetheart the Drunk CD 782.42 BUC AA. -

AMY Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com AMY Discussion Guide Director: Asif Kapadia Year: 2015 Time: 128 min You might know this director from: Ali and Nino (2016) Senna (2010) Far North (2007) The Return (2006) The Warrior (2001) FILM SUMMARY If you live in the Western World and have access to the mainstream press in any capacity, you’ve most likely heard of Amy Winehouse. Regardless of your knowledge of her before spending two hours in her filmic company, you probably have some notion of her - in many cases, not the most squeaky clean perception. Whenever Amy made it into the headlines, it was generally some kind of self-damaging drama that dragged her there. So when asked by Universal Records to make a documentary on the life of this renowned international pop star, director Asif Kapadia felt compelled to challenge the widely accepted notion of Amy as a train wreck. Lucky for him, hours and hours of amateur footage was offered his way, portraying a younger, fresher, happier, and healthier Amy, a young woman as of yet untouched by the destructive claws of fame, money, and addiction. Over the course of 128 hypnotic minutes, Kapadia takes us on a chronological ride through Amy’s short-lived time on earth. By adopting this approach, he grasps his audience by the heartstrings with early images of a charming and very talented young woman. As time progresses and success tsunamis her way, the natural arch of her life, however fast-lived, gains a clearer context, as does her untimely death. Despite the cast of dubious relationships and her substance-abusing decisions, Amy maintained an incredible natural talent up until her death. -

Amy Winehouse Full Album Download

Amy winehouse full album download LINK TO DOWNLOAD Artist: Amy Winehouse Album: Back To Black Label: IUniversal Republic Genre: R&b, Soul Quality: MP3 Bitrate: kbps (Scans). Aug 25, · Yuk tambah koleksi lagu Anda, dengan download lagu MP3 Amy Winehouse Full Album dalam artikel ini. Amy Winehouse adalah seorang penyanyi dan pencipta lagu soul, jazz, dan R&B dari Inggris. Penyanyi yang memiliki nama lengkap Amy Jade Winehouse ini lahir di Southgate, London, Inggris, 14 September dan meninggal di London, Inggris, Amy Jade Winehouse (September 14, – July 23, ) was an English-born singer and songwriter best known for her powerful contralto vocal range and her eclectic mix of musical. Apr 01, · 13 – Amy Amy Amy Outro. CD2. 01 – Take The Box (Demo) 02 – You Sent Me Flying (Demo) 03 – I Heard Love Is Blind (Demo) 04 – Someone To Watch Over Me (Demo) 05 – What It Is (Demo) 06 – Teach Me Tonight (Live At The Hootenanny, London ) 07 – ’round Midnight 08 – Fool’s Gold 09 – Stronger Than Me (Later With Jools. Posted in Amy Winehouse, Banda, Jazz, R&B, Ska, Soul Amy Winehouse – Discografia Author: dener Published Date: Janeiro 17, Leave a Comment on Amy Winehouse – Discografia. The discography of English singer and songwriter Amy Winehouse consists of two studio albums, one live album, three compilation albums, four extended plays, 14 singles (including three as a featured artist), three video albums and 14 music renuzap.podarokideal.ru the time of her death on 23 July , Winehouse had sold over million singles and over million albums in the United Kingdom. The first track is a slower version of the Zutons’ song “Valerie” that Winehouse had done earlier with Mark Ronson for Ronson’s Version album (and also featured in the film 27 Dresses).