Living on 'Scenery and Fresh Air': Land-Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Come Celebrate! [email protected] 1-866-944-1744

Gulf Islands National Park Reserve parkscanada.gc.ca Come Celebrate! [email protected] 1-866-944-1744 Parks Pares Canada Canada Canada TABLE OF CONTENTS Contact Information 2 Welcome to Gulf Islands National Park Reserve, one of Programs 5 Top 10 Experiences 6-7 Canada's newest national parks. Established in 2003, it First Nations 8-9 Camping & Mooring 10 Trails 11 safeguards a portion of British Columbia's beautiful southern BC Ferries Coastal Naturalist Program 12 Gulf Islands in the Strait of Georgia. A mosaic of open Map 12-13 Species at Risk 14-15 meadows, forested hills, rocky headlands, quiet coves and Marine Wildlife Viewing 14-15 Extreme Take-Over 16 Did You Know? 17 sandy beaches, the park is a peaceful refuge just a stone's Ecological Integrity 17 Sidney Spit, D'Arcy throw from the urban clamour ofVancouver and Victoria. Island & Isle-de-Lis 18 Princess Margaret (Portland Is.), Brackman & Russell Islands 19 Pender Islands 20 Mayne Island 21 Saturna Island 22-23 Tumbo & Cabbage Islands 23 CONTACT INFORMATION Website information www.parkscanada.gc.ca/gulf Emergency and Important Phone Numbers Emergency call 911 In-Park Emergency or to report an offence 1-877-852-3100 Report a Wildfire 1-800-663-5555 (*5555 on cell phones) Marine Distress VHF Channel 16 Park Office • 250-654-4000 Toll Free 1-866-944-1744 Sidney Operations Centre 2220 Harbour Road Sidney, B.C. V8L 2P6 RCMP detachment offices located in Sidney, on the Penders, and on Mayne Island. Wflp\,t to teiA/OW pvu>re? The park offers many activities and learning opportunities. -

Status and Distribution of Marine Birds and Mammals in the Southern Gulf Islands, British Columbia

Status and Distribution of Marine Birds and Mammals in the Southern Gulf Islands, British Columbia. Pete Davidson∗, Robert W Butler∗+, Andrew Couturier∗, Sandra Marquez∗ & Denis LePage∗ Final report to Parks Canada by ∗Bird Studies Canada and the +Pacific WildLife Foundation December 2010 Recommended citation: Davidson, P., R.W. Butler, A. Couturier, S. Marquez and D. Lepage. 2010. Status and Distribution of Birds and Mammals in the Southern Gulf Islands, British Columbia. Bird Studies Canada & Pacific Wildlife Foundation unpublished report to Parks Canada. The data from this survey are publicly available for download at www.naturecounts.ca Bird Studies Canada British Columbia Program, Pacific Wildlife Research Centre, 5421 Robertson Road, Delta British Columbia, V4K 3N2. Canada. www.birdscanada.org Pacific Wildlife Foundation, Reed Point Marine Education Centre, Reed Point Marina, 850 Barnet Highway, Port Moody, British Columbia, V3H 1V6. Canada. www.pwlf.org Contents Executive Summary…………………..……………………………………………………………………………………………1 1. Introduction 1.1 Background and Context……………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 1.2 Previous Studies…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 2. Study Area and Methods 2.1 Study Area……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 2.2 Transect route……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 2.3 Kernel and Cluster Mapping Techniques……………………………………………………………………………..7 2.3.1 Kernel Analysis……………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 2.3.2 Clustering Analysis………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 2.4 -

SOUTHERN GULF ISLANDS VANCOUVER ISLAND SEWERED AREAS (SANITARY SEWERS) Mainland

SOUTHERN GULF ISLANDS VANCOUVER ISLAND SEWERED AREAS (SANITARY SEWERS) Mainland Area of Interest PENELAKUT FIRST Dioniso Point NATION Provincial Park CANADAU.S.A Porlier Pass Rd Secretary Islands Bodega Ridge Provincial Park Houstoun Passage Strait of Pebble Beach DL 63 Pebble Beach Georgia DL 60 Wallace Island N N o o Galiano Island r r t th h B E e a n c Porlier Pass Rd d h R R r d d D t e s n u S Maliview Wastewater Treatment Plant Fernwood Trincomali Channel Heritage W Forest a l k e Montague r s Harbour H o o Marine k Finlay R Park d Po Lake rlie Clanton Rd r P ass Rd St Whaler Bay Ch Mary an Montague Harbour Gossip n Stu e Lake rd l R ie Island idg s Stuart Channel e D Sta Parker B r rks Rd M a on y Island tag R ue Rd Galiano d R Payne Bay Vesuvius o Ba b y R in d so n R Bluff Park B u Bullocks d r M r Lake an i l se l ll R R d d Booth Bay Bluff Rd Active Pass Lower Ganges Rd Ganges Lower Mt. Galiano Wa ugh Georgina Point Rd Rd N Active Pass os d e R d R Salt Spring L R a on P y i Elementary g Long Harbour oi a s n n bo Ha t B n w r ll i Rd Gulf Islands b R l e l ou d b r o Salt Spring R d p C m Island Middle a Ganges Wastewater TSARTLIP FIRST C Treatment Plant Mount Erskine NATION F ernh Provincial Park Phoenix ill Rd Fe Rd Mayne Island e Ba lix J a ck ag y ill Rd Dalton DrV Ganges Harbour Mayne Island Fulford-Ganges Rd M Captain Passage arine rs C W ra a d n y ay R b e B rry Rd r e Roberts h g a Lake ll Prevost Island a Gulf Islands G National Park Reserve (Water Extension) Lake Salt Spring Navy Channel Maxwell Centre Samuel Island -

Gulf Islands Gulf Islands

Gulf Islands national park reserve of canada visitor guide brochure with map inside! TABLE OF CONTENTS Contact Information 2 Programs 5 Top 10 Experiences 6-7 Enjoy the Park 6-9 Welcome to Gulf Islands National Park Reserve, one of Camping 8 Trails 9 Canada’s newest national parks. Established in 2003, it First Nations 10-11 Species at Risk 12-13 safeguards a portion of British Columbia’s beautiful southern Marine Wildlife Viewing 12-13 Extreme Take-Over 14 Did You Know? 15 Gulf Islands in the Strait of Georgia. A mosaic of open Ecological Integrity 15 Sidney Spit, D’Arcy meadows, forested hills, rocky headlands, quiet coves and Island & Isle-de-Lis 16 Portland, Brackman & Russell Islands 17 sandy beaches, the park is a peaceful refuge just a stone’s Pender Islands 18 Mayne Island 19 throw from the urban clamour of Vancouver and Victoria. Saturna Island 20-21 Tumbo & Cabbage Islands 21 Map 22 Pullout brochure Additional Camping & Hiking Information CONTACT INFORMATION Website information www.pc.gc.ca/gulf Emergency and important phone numbers Emergency call 911 In-Park Emergency or to report an offence 1-877-852-3100 Report a Wildfire 1-800-663-5555 (*5555 on cell phones) Marine Distress VHF Channel 16 Park Offices • Sidney 250-654-4000 Toll Free 1-866-944-1744 • Saturna 250-539-2982 • Pender 250-629-6137 Address & office locations Did this visitor guide meet your needs? Let us know and you might win a $200 gift certificate from Mountain Equipment Sidney Operations Centre Co-op. Log on to www.parkscanadasurveys.ca to participate in an on-line survey. -

Order in Council 2315/1966

2315. Approved and ordered this 5th day of August , A.D. 19 66. At the Executive Council Chamber, Victoria, Lieutenant-Governor. PRESENT: The Honourable in the Chair. Mr. Martin Mr. Black Mr. Bonner Mr. Villiston Mr. Brothers Mr. Gaglardi Mr. Peterron Mr. Loffmark Mr. Campbell Mr. Chant Mr. Kinrnan Mr. Mr. Mr. To His Honour (c77/77 The Lieutenant-Governor in Council: The undersigned has the honour to recommend X 4,14 49/to •‘4":7151° 0 A ••>/v ',4 / THAT under the provisions of Section 34 of the "Provincial Elections Act" being Chapter 306 of the Revised Statutes of British Columbia, 1960" each of the persons whose names appear on the list attached hereto be appointed Returning Officer in and for the electoral district set out opposite their respective names; AND THAT the appointments of Returning Officers heretofor made are hereby rescinded. DATED this day of August A.D. 1966 Provincial Secretary APPROVED this day of Presiding Member of the Executive Council Returning Officers - 1966 Electoral District Name Alberni Thomas Johnstone, Port Alberni Atlin Alek S. Bill, Prince Rupert Boundary-Similkameen A. S. Wainwright, Cawston Burnaby-Edmond s W. G. Love, Burnaby Burnaby North E. D. Bolick, Burnaby Burnaby-Willingdon Allan G. LaCroix, Burnaby Cariboo E. G. Woodland, Williams Lake Chilliwack Charles C. Newby, Sardis Columbia River T. J. Purdie, Golden Comox W. J. Pollock, Comox Coquitlam A. R. Ducklow, New Westminster Cowichan-Malahat Cyril Eldred, Cobble Hill Delta Harry Hartley, Ladner Dewdney Mrs. D. J. Sewell, Mission Esquimalt H. F. Williams, Victoria Fort George John H. Robertson, Prince George Kamloops Edwin Hearn, Kamloops Kootenay Mrs. -

Order in Council 1780/1986

COLUMBIA 1780 APPROVED AND ORDERED SEP 24.1986 Lieutenant-Governer EXECUTIVE COUNCIL CHAMBERS, VICTORIA SEP 24.1986 On the recommendation of the undersigned, the Lieutenant-Governor, by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, orders that a general election be held in all the electoral districts for the election of members to serve in the Legislative Assembly; AND FURTHER ORDERS THAT Writs of Election be issued on September 24, 1986 in accordance with Section 40 of the Election Act; AND THAT in each electoral district the place for the nomination of candidates for election to membership and service in the Legislative Assembly shall be the office of the Returning Officer; AND THAT A Proclamation to that end be made. ...-- • iti PROVINCI1‘( ,IT/ ECRETARYT(' AND MINISTER OF GOVERNMENT SERVICES PRESIDING MEMBER OF THE E ECUTIVE COUNCIL (This part is for administrative purposes and it not part of the Order.) Authority under which Order is made: Election Act - sec. 33 f )40 Act and section. Other (specify) Statutory authority checked r9Z 4,4fAr 6-A (Signet, typed or printed name of Legal OfOra) ELECTION ACT WRIT OF ELECTION FORM 1 (section 40) ELIZABETH II, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom, Canada and Her Other Realms and Territories, QUEEN, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith. To the Returning Officer of the Electoral District of Coquitlam-Moody GREETING: We command you that, notice of time and place of election being given, you do cause election to be made, according to law, of a member (or members -

Tisdalle Holds Seat FULFORD WHARF RESTRICTED Ferries Full

j*. .. G. Wells, Vesvuius Bay Road, R, Rr 1, •'Ganges^ B.C "- ulf 3telan&? Brifttooob Tenth Year, No 36 GANGES, British Columbia Thursday, September 4, 1969 $4.00 per year. Copy Tisdalle Holds Seat ISLAND WHARFS FALLING APART FULFORD WHARF RESTRICTED Saanich and the Islands: PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURE: SECOND SALT SPRING FERRY LIMIT Tisdalle (Soc. Credit) 9577 Social Credit 39 Johannessen (NDP) 6791 New Democrats 11 Lindholm (Liberal) 3228 Liberal 5 Concrete is an aggravation on with a gross weight of less than Salt Spring Island as wharfs ser- 10 tons, the bottom fell out of END OF SUMMER ving the island are collapsing the Fulford wharf and without PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURE: 1969 from heavy weights. warning traffic was reduced to a Time was when a contractor maximum of big pick-ups. Social Credit 31 Liberal 6 could call a supplier and have New Democrats 17 (One seat not filled) m Ferries his concrete delivered and Heaviest traffic was heaviest poured within 24 hours. That hit. Concrete truck with the time is past. John Tisdalle will serve again counting there was little doubt Run Island contractors are turning (Turn to Page Two) in the provincial legislature. On of the results. As poll after poll to locally produced concrete Wednesday last weeK Saanich supported the Social Credit can- and specialists in concrete are and the Islands gave him a didate, reports were already bringing in gravel to be mixed handsome margin over his near- coming in of the provincial on the island. BRILLIANT est contestant for the seat he landslide to the Bennett govern- Full »*•»»»•»»»»»»»»»»»»»»• has held for 17 years. -

Rainwater Availability and Household Water Consumption for Mayne Island

MADRONE environmental services ltd. RAINWATER AVAILABILITY AND HOUSEHOLD WATER CONSUMPTION FOR MAYNE ISLAND for: Gerry Hamblin The Islands Trust by: Ken Hughes-Adams, M.Eng.,P.Eng. Madrone Environmental Services Ltd. and Bob Burgess Gulf Islands Rainwater Connection Ltd. October 30, 2006 Dossier 06.0122 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................1 2.0 RAINWATER AVAILABILITY ...................................................................2 2.1 Methodology............................................................................................2 2.2 Recent Climatic Conditions .....................................................................3 2.2.1 Spatial Trends in Precipitation .......................................................5 2.2.2 Extreme Dry Conditions .................................................................7 2.3 Future Climatic Conditions......................................................................8 3.0 HOUSEHOLD WATER CONSUMPTION ..............................................11 3.1 Methodology..........................................................................................11 3.2 Estimated 2005 Residential Household Water Use................................12 3.3 Seasonal Variations in Residential Water Use........................................14 3.4 Non-potable Water Use.........................................................................15 3.5 Factors Influencing Future Water Consumption....................................17 -

The Damnation of a Dam : the High Ross Dam Controversy

THE DAMYIATION OF A DAM: TIIE HIGH ROSS DAM CONTROVERSY TERRY ALLAN SIblMONS A. B., University of California, Santa Cruz, 1968 A THESIS SUBIUTTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Geography SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY May 1974 All rights reserved. This thesis may not b? reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Terry Allan Simmons Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: The Damnation of a Dam: The High Ross Dam Controversy Examining Committee: Chairman: F. F. Cunningham 4 E.. Gibson Seni Supervisor / /( L. J. Evendon / I. K. Fox ernal Examiner Professor School of Community and Regional Planning University of British Columbia PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University rhe righc to lcnd my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed ' without my written permission. Title of' ~hesis /mqqmkm: The Damnation nf a nam. ~m -Author: / " (signature ) Terrv A. S.imrnonze (name ) July 22, 1974 (date) ABSTRACT In 1967, after nearly fifty years of preparation, inter- national negotiations concerning the construction of the High Ross Dan1 on the Skagit River were concluded between the Province of British Columbia and the City of Seattle. -

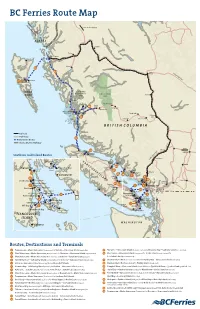

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver -

Religious and Social Influences on Voting in Greater Victoria*

Religious and Social Influences on Voting in Greater Victoria* T. RENNIE WARBURTON The detailed investigation of voting behaviour by social scientists has shown that the idea that voters are informed, rational and public spirited and that they carefully weigh the pros and cons of policy before casting their ballots is invalid and at best a means of legitimating the political theory underlying democratic elections. Not only has it been shown that large segments of the electorate are ignorant of such matters as party platforms, the party that particular candidates represent and even the identity of major party leaders, but that political behaviour is better explained as a product of social experience than as the exercise of rational choice.1 Social experience in this context is usually seen in terms of such factors as age, sex, parents' party preferences and social class, the latter being measured either by such objective indices as occupation, income or level of educational achievement or by more subjective ones such as in which social class electors place themselves. In national elec tions held since World War II a considerable segment of the electorate in North America, the United Kingdom and a number of continental European and Commonwealth countries, appears to have voted con sistently for the same party, regardless of the main issues involved. These consistent voting patterns have been directly related to various socio economic factors and, particularly in Canada, to religion. John Meisel, in one of the earliest Canadian analyses of electoral behaviour, reported finding a relationship between religious affiliation and voting preferences in the 1953 Federal and the 1955 Provincial * Thanks are due to David Goburn and Clyde Pope for helpful criticism of an earlier draft of this paper. -

Soils of the Gulf Islands of British Columbia Volume 2 Soils of North Pender, South Pender Prevost, Mayne, Saturna, and Lesser Islands

Soils of the Gulf Islands of British Columbia Volume 2 Soils of North Pender, South Pender Prevost, Mayne, Saturna, and lesser islands Report No. 43 British Columbia Soi1 Survey E.A. Kenney, L.J.P. van Vliet, and A.J. Green B.C. Soi1 Survey Unit Land Resource Research Centre Vancouver, B.C. Land Resource Research Centre Contribution No. 86-76 (Accompanying Map sheets from Soils of the Gulf Islands of British Columbia series: * North Pender, South Pender, and Prevost islands + Mayne and Saturna islands) Research Branch Agriculture Canada 1988 Copies of this publication are available from Maps B.C. Ministry of Environment Parliament Buildings Victoria, B.C. vav 1x5 o Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1988 CAt. No.: A57-426/2E ISBN: O-662-16258-7 Caver photo: Boot Cave, Saturna Island, looking towards Samuel Island. Courtesy: Province of British Columbia Staff editor: Jane T. Buckley iii CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. vii . PREFACE. ..Vlll PART 1. INTRODUCTION............................................. 1 PART 2. GENERALDESCRIPTION OF THE AREA.......................... 3 Location and extent ............................................ 3 History and development ........................................ 3 Climate ........................................................ 11 Natural vegetation ............................................. 11 Geology ........................................................ 15 Physiography ................................................... 16 Soi1 parent materials .........................................