The Implementation of the National Security Law for Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

Head 122 — HONG KONG POLICE FORCE

Head 122 — HONG KONG POLICE FORCE Controlling officer: the Commissioner of Police will account for expenditure under this Head. Estimate 2002–03................................................................................................................................... 12,445.8m Establishment ceiling 2002–03 (notional annual mid-point salary value) representing an estimated 34 597 non-directorate posts at 31 March 2002 reducing by 337 posts to 34 260 posts at 31 March 2003......................................................................................................................................... 9,473.1m In addition there will be 77 directorate posts at 31 March 2002 and at 31 March 2003. Capital Account commitment balance................................................................................................. 305.3m Controlling Officer’s Report Programmes Programme (1) Maintenance of Law and These programmes contribute to Policy Area 9: Internal Security Order in the Community (Secretary for Security). Programme (2) Prevention and Detection of Crime Programme (3) Reduction of Traffic Accidents Programme (4) Operations Detail Programme (1): Maintenance of Law and Order in the Community 2000–01 2001–02 2001–02 2002–03 (Actual) (Approved) (Revised) (Estimate) Financial provision ($m) 6,223.6 5,995.3 5,986.4 6,081.8 (–3.7%) (–0.1%) (+1.6%) Aim 2 The aim is to maintain law and order through the deployment of efficient and well-equipped uniformed police personnel throughout the land regions. Brief Description 3 Law -

Dissenting Media in Post-1997 Hong Kong Joyce Y.M. Nip the De

Dissenting media in post-1997 Hong Kong Joyce Y.M. Nip The de-colonization of Hong Kong took the form of Britain returning the territory to China in 1997 as a Special Administrative Region (SAR). Twenty years after the political handover, the “one country, two systems” arrangement designed by China to govern the Hong Kong SAR is facing serious challenge: Many in Hong Kong have come to regard Beijing as an unwelcome control master; and calls for self-determination have gained a substantial level of popular support. This chapter examines the role of media in this development, as exemplified by key political protest actions. It proposes the notion of “dissenting media” as a framework to integrate relevant academic and journalistic studies about Hong Kong. From the discipline of media and communications study, it suggests that operators of dissenting media are enabled to put forth information and analysis contrary to that of the establishment, which, in turn, help to form an oppositional public sphere. In the process, the identity and communities of dissent are built, maintained, and developed, contributing to the formation of a counter public that participates in oppositional political actions. Studies on the impact of media, mainly conducted in stable Anglo-American societies, tend to consider mainstream media as institutions that index1 or reinforce the status quo,2 and alternative media as forces that challenge established powers.3 In Hong Kong, the 1997 political changeover was accompanied by a reconfiguration of power relationships in line with China’s one-party dictatorship. The change runs counter to the political aspirations of the people of Hong Kong, and has bred a political movement for civil liberties, public accountability, and democracy. -

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: a Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Tso, Elizabeth Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 12:25:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623063 DISCOURSE, SOCIAL SCALES, AND EPIPHENOMENALITY OF LANGUAGE POLICY: A CASE STUDY OF A LOCAL, HONG KONG NGO by Elizabeth Ann Tso __________________________ Copyright © Elizabeth Ann Tso 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Elizabeth Tso, titled Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO, and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Perry Gilmore _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Wenhao Diao _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Sheilah Nicholas Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Yours Truly 2021

Region Name Country Information Mailing Address Gender Africa Yahaya Sharif Aminu Nigeria 22-year old singer at risk of execution after being sentenced Yahaya Sharif-Aminu Male to death by hanging for circulating a song via WhatsApp Nigerian Correctional Service considered blasphemous. Kano State Command c/of Nigeria Correctional Service National Headquarters Bill Clinton Drive, Airport Road. P.M.B 16 Garki Abuja. Nigeria MENA Ruba Asi Palestine Ruba Asi a Palestinian student who has been in military Ruba Asi Female detention since 9 July 2020, she is currently charged with Damon Prison participation and affiliation with a democratic student P.O. Box 98 political group at Birzeit University. Daliyat al-Karmel Israel Europe & EECA Julian Assange Austrialia Julian Assange is an Australian journalist who founded Julian Assange Male WikiLeaks in 2006. He is being sought by the current US DOB 3 July 1971 administration for publishing US government documents #A9379AY which exposed war crimes and human rights abuses. The HMP Belmarsh politically motivated charges represent an unprecedented Western Way attack on press freedom and the public’s right to know – London SE28 0EB seeking to criminalise basic journalistic activity. United Kingdom If convicted Julian Assange faces a sentence of 175 years, likely to be spent in extreme isolation. MENA Marwan Barghouti Palestine Marwan Barghouti is the Secretary-General of Fatah in the Marwan Barghouti Male West Bank. He was arrested in 2002 and sentenced to five Hadarim Prison life sentences and 40 years. P.O. Box 165 Even Yehuda 405000 Israel Asia "Slow beat" Hong Kong Currently charged under conspiracy to commit subversion. -

The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy

Loyola University Chicago International Law Review Volume 3 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring/Summer 2006 2006 The aB sic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong Michael C. Davis Chinese University of Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael C. Davis The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy. U. Chi. Int'l L. Rev. 165 (2006). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr/vol3/iss2/5 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago International Law Review by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BASIC LAW AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN HONG KONG Michael C. Davist I. Introduction Hong Kong's status as a Special Administrative Region of China has placed it on the foreign policy radar of most countries having relations with China and interests in Asia. This interest in Hong Kong has encouraged considerable inter- est in Hong Kong's founding documents and their interpretation. Hong Kong's constitution, the Hong Kong Basic Law ("Basic Law"), has sparked a number of debates over democratization and its pace. It is generally understood that greater democratization will mean greater autonomy and vice versa, less democracy means more control by Beijing. For this reason there is considerable interest in the politics of interpreting Hong Kong's Basic Law across the political spectrum in Hong Kong, in Beijing and in many foreign capitals. -

The Chief Executive's 2020 Policy Address

The Chief Executive’s 2020 Policy Address Striving Ahead with Renewed Perseverance Contents Paragraph I. Foreword: Striving Ahead 1–3 II. Full Support of the Central Government 4–8 III. Upholding “One Country, Two Systems” 9–29 Staying True to Our Original Aspiration 9–10 Improving the Implementation of “One Country, Two Systems” 11–20 The Chief Executive’s Mission 11–13 Hong Kong National Security Law 14–17 National Flag, National Emblem and National Anthem 18 Oath-taking by Public Officers 19–20 Safeguarding the Rule of Law 21–24 Electoral Arrangements 25 Public Finance 26 Public Sector Reform 27–29 IV. Navigating through the Epidemic 30–35 Staying Vigilant in the Prolonged Fight against the Epidemic 30 Together, We Fight the Virus 31 Support of the Central Government 32 Adopting a Multi-pronged Approach 33–34 Sparing No Effort in Achieving “Zero Infection” 35 Paragraph V. New Impetus to the Economy 36–82 Economic Outlook 36 Development Strategy 37 The Mainland as Our Hinterland 38–40 Consolidating Hong Kong’s Status as an International Financial Centre 41–46 Maintaining Financial Stability and Striving for Development 41–42 Deepening Mutual Access between the Mainland and Hong Kong Financial Markets 43 Promoting Real Estate Investment Trusts in Hong Kong 44 Further Promoting the Development of Private Equity Funds 45 Family Office Business 46 Consolidating Hong Kong’s Status as an International Aviation Hub 47–49 Three-Runway System Development 47 Hong Kong-Zhuhai Airport Co-operation 48 Airport City 49 Developing Hong Kong into -

Regulating Undercover Agents' Operations and Criminal

This document is downloaded from CityU Institutional Repository, Run Run Shaw Library, City University of Hong Kong. Regulating undercover agents’ operations and criminal Title investigations in Hong Kong: What lessons can be learnt from the United Kingdom and South Australia Author(s) Chen, Yuen Tung Eutonia (陳宛彤) Chen, Y. T. E. (2012). Regulating undercover agents’ operations and criminal investigations in Hong Kong: What lessons can be learnt Citation from the United Kingdom and South Australia (Outstanding Academic Papers by Students (OAPS)). Retrieved from City University of Hong Kong, CityU Institutional Repository. Issue Date 2012 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2031/6855 This work is protected by copyright. Reproduction or distribution of Rights the work in any format is prohibited without written permission of the copyright owner. Access is unrestricted. Page | 1 LW 4635 INDEPENDENT RESEARCH Topic: Regulating Undercover Agents’ Operations and Criminal Investigations in Hong Kong: What Lessons can be learnt from the United Kingdom and South Australia? Student Name: CHEN Yuen Tung Eutonia1 Date: 13th April 2012 Word Count: 9570 (excluding cover page, footnote and bibliography) Number of Pages: 39 Abstract It is not a dispute that undercover police officers have a proper role to play in contemporary law enforcement. However, there is no clear legislation in Hong Kong on the issue of whether the undercover agent is, at law, an offender of crime(s). This paper would examine the limitations of the prevailing undercover policing laws in Hong Kong and suggest possible recommendations. In particular, a comparative study of the United Kingdom and South Australia would be made to investigate whether Hong Kong should enact a legislation regulating undercover operations and criminal investigations. -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2003: China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong and Macau)

Page 1 of 66 China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau) Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 (Note: Also see the section for Tibet, the report for Hong Kong, and the report for Macau.) The People's Republic of China (PRC) is an authoritarian state in which, as directed by the Constitution, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP or Party) is the paramount source of power. Party members hold almost all top government, police, and military positions. Ultimate authority rests with the 24-member political bureau (Politburo) of the CCP and its 9-member standing committee. Leaders made a top priority of maintaining stability and social order and were committed to perpetuating the rule of the CCP and its hierarchy. Citizens lacked both the freedom peacefully to express opposition to the Party-led political system and the right to change their national leaders or form of government. Socialism continued to provide the theoretical underpinning of national politics, but Marxist economic planning has given way to pragmatism, and economic decentralization increased the authority of local officials. The Party's authority rested primarily on the Government's ability to maintain social stability; appeals to nationalism and patriotism; Party control of personnel, media, and the security apparatus; and continued improvement in the living standards of most of the country's 1.3 billion citizens. The Constitution provides for an independent judiciary; however, in practice, the Government and the CCP, at both the central and local levels, frequently interfered in the judicial process and directed verdicts in many high-profile cases. -

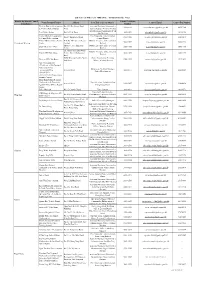

List of Access Officer (For Publication)

List of Access Officer (for Publication) - (Hong Kong Police Force) District (by District Council Contact Telephone Venue/Premise/FacilityAddress Post Title of Access Officer Contact Email Conact Fax Number Boundaries) Number Western District Headquarters No.280, Des Voeux Road Assistant Divisional Commander, 3660 6616 [email protected] 2858 9102 & Western Police Station West Administration, Western Division Sub-Divisional Commander, Peak Peak Police Station No.92, Peak Road 3660 9501 [email protected] 2849 4156 Sub-Division Central District Headquarters Chief Inspector, Administration, No.2, Chung Kong Road 3660 1106 [email protected] 2200 4511 & Central Police Station Central District Central District Police Service G/F, No.149, Queen's Road District Executive Officer, Central 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Central and Western Centre Central District Shop 347, 3/F, Shun Tak District Executive Officer, Central Shun Tak Centre NPO 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Centre District 2/F, Chinachem Hollywood District Executive Officer, Central Central JPC Club House Centre, No.13, Hollywood 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 District Road POD, Western Garden, No.83, Police Community Relations Western JPC Club House 2546 9192 [email protected] 2915 2493 2nd Street Officer, Western District Police Headquarters - Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Office Building & Facilities Manager, - Licensing office Arsenal Street 2860 2171 [email protected] 2200 4329 Police Headquarters - Shroff Office - Central Traffic Prosecutions Enquiry Counter Hong Kong Island Regional Headquarters & Complaint Superintendent, Administration, Arsenal Street 2860 1007 [email protected] 2200 4430 Against Police Office (Report Hong Kong Island Room) Police Museum No.27, Coombe Road Force Curator 2849 8012 [email protected] 2849 4573 Inspector/Senior Inspector, EOD Range & Magazine MT. -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations.