Brian Katulis Senior Fellow, Center for American Progress Washington, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS): an Al-Qaeda Affiliate Case Study Pamela G

Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS): An Al-Qaeda Affiliate Case Study Pamela G. Faber and Alexander Powell October 2017 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Distribution DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. SPECIFIC AUTHORITY: N00014-16-D-5003 10/27/2017 Request additional copies of this document through [email protected]. Photography Credit: Michael Markowitz, CNA. Approved by: October 2017 Dr. Jonathan Schroden, Director Center for Stability and Development Center for Strategic Studies This work was performed under Federal Government Contract No. N00014-16-D-5003. Copyright © 2017 CNA Abstract Section 1228 of the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) states: “The Secretary of Defense, in coordination with the Secretary of State and the Director of National Intelligence, shall provide for the conduct of an independent assessment of the effectiveness of the United States’ efforts to disrupt, dismantle, and defeat Al- Qaeda, including its affiliated groups, associated groups, and adherents since September 11, 2001.” The Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations/Low Intensity Conflict (ASD (SO/LIC)) asked CNA to conduct this independent assessment, which was completed in August 2017. In order to conduct this assessment, CNA used a comparative methodology that included eight case studies on groups affiliated or associated with Al-Qaeda. These case studies were then used as a dataset for cross-case comparison. This document is a stand-alone version of the Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) case study used in the Independent Assessment. -

Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan

Fall 08 September 2012 Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School Global Justice Clinic http://livingunderdrones.org/ NYU School of Law Cover Photo: Roof of the home of Faheem Qureshi, a then 14-year old victim of a January 23, 2009 drone strike (the first during President Obama’s administration), in Zeraki, North Waziristan, Pakistan. Photo supplied by Faheem Qureshi to our research team. Suggested Citation: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION CLINIC (STANFORD LAW SCHOOL) AND GLOBAL JUSTICE CLINIC (NYU SCHOOL OF LAW), LIVING UNDER DRONES: DEATH, INJURY, AND TRAUMA TO CIVILIANS FROM US DRONE PRACTICES IN PAKISTAN (September, 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I ABOUT THE AUTHORS III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS V INTRODUCTION 1 METHODOLOGY 2 CHALLENGES 4 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 7 DRONES: AN OVERVIEW 8 DRONES AND TARGETED KILLING AS A RESPONSE TO 9/11 10 PRESIDENT OBAMA’S ESCALATION OF THE DRONE PROGRAM 12 “PERSONALITY STRIKES” AND SO-CALLED “SIGNATURE STRIKES” 12 WHO MAKES THE CALL? 13 PAKISTAN’S DIVIDED ROLE 15 CONFLICT, ARMED NON-STATE GROUPS, AND MILITARY FORCES IN NORTHWEST PAKISTAN 17 UNDERSTANDING THE TARGET: FATA IN CONTEXT 20 PASHTUN CULTURE AND SOCIAL NORMS 22 GOVERNANCE 23 ECONOMY AND HOUSEHOLDS 25 ACCESSING FATA 26 CHAPTER 2: NUMBERS 29 TERMINOLOGY 30 UNDERREPORTING OF CIVILIAN CASUALTIES BY US GOVERNMENT SOURCES 32 CONFLICTING MEDIA REPORTS 35 OTHER CONSIDERATIONS -

Testimony of Thomas Joscelyn Senior Fellow, Foundation for Defense Of

Testimony of Thomas Joscelyn Senior Fellow, Foundation for Defense of Democracies Senior Editor, The Long War Journal Before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade United States Congress “Global al-Qaeda: Affiliates, Objectives, and Future Challenges” July 18, 2013 1 Chairman Poe, Ranking Member Sherman and members of the Committee, thank you for inviting me here today to discuss the threat posed by al Qaeda. We have been asked to “examine the nature of global al Qaeda today.” In particular, you asked us to answer the following questions: “What is [al Qaeda’s] makeup? Is there a useful delineation between al Qaeda’s core and its affiliates? If so, what is the relationship? Most importantly, what is the threat of al Qaeda to the United States today?” I provide my answers to each of these questions in the following sections. But first, I will summarize my conclusions: • More than a decade after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks there is no commonly accepted definition of al Qaeda. There is, in fact, widespread disagreement over what exactly al Qaeda is. • In my view, al Qaeda is best defined as a global international terrorist network, with a general command in Afghanistan and Pakistan and affiliates in several countries. Together, they form a robust network that, despite setbacks, contests for territory abroad and still poses a threat to U.S. interests both overseas and at home. • It does not make sense to draw a firm line between al Qaeda’s “core,” which is imprecisely defined, and the affiliates. -

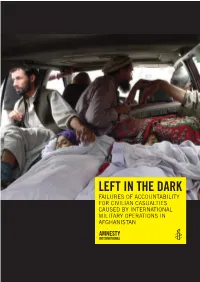

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent: a New Frontline in the Global Jihadist Movement?” the International Centre for Counter- Ter Rorism – the Hague 8, No

AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT: The Nucleus of Jihad in South Asia THE SOUFAN CENTER JANUARY 2019 AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT: THE NUCLEUS OF JIHAD IN SOUTH ASIA !1 AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT: THE NUCLEUS OF JIHAD IN SOUTH ASIA AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT (AQIS): The Nucleus of Jihad in South Asia THE SOUFAN CENTER JANUARY 2019 !2 AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT: THE NUCLEUS OF JIHAD IN SOUTH ASIA CONTENTS List of Abbreviations 4 List of Figures & Graphs 5 Key Findings 6 Executive Summary 7 AQIS Formation: An Affiliate with Strong Alliances 11 AQIS Leadership 19 AQIS Funding & Finances 24 Wahhabization of South Asia 27 A Region Primed: Changing Dynamics in the Subcontinent 31 Global Threats Posed by AQIS 40 Conclusion 44 Contributors 46 About The Soufan Center (TSC) 48 Endnotes 49 !3 AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT: THE NUCLEUS OF JIHAD IN SOUTH ASIA LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AAI Ansar ul Islam Bangladesh ABT Ansar ul Bangla Team AFPAK Afghanistan and Pakistan Region AQC Al-Qaeda Central AQI Al-Qaeda in Iraq AQIS Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas HUJI Harkat ul Jihad e Islami HUJI-B Harkat ul Jihad e Islami Bangladesh ISI Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence ISKP Islamic State Khorasan Province JMB Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh KFR Kidnap for Randsom LeJ Lashkar e Jhangvi LeT Lashkar e Toiba TTP Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan !4 AL-QAEDA IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT: THE NUCLEUS OF JIHAD IN SOUTH ASIA LIST OF FIGURES & GRAPHS Figure 1: Map of South Asia 9 Figure 2: -

Political Islam: a 40 Year Retrospective

religions Article Political Islam: A 40 Year Retrospective Nader Hashemi Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, Denver, CO 80208, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The year 2020 roughly corresponds with the 40th anniversary of the rise of political Islam on the world stage. This topic has generated controversy about its impact on Muslims societies and international affairs more broadly, including how governments should respond to this socio- political phenomenon. This article has modest aims. It seeks to reflect on the broad theme of political Islam four decades after it first captured global headlines by critically examining two separate but interrelated controversies. The first theme is political Islam’s acquisition of state power. Specifically, how have the various experiments of Islamism in power effected the popularity, prestige, and future trajectory of political Islam? Secondly, the theme of political Islam and violence is examined. In this section, I interrogate the claim that mainstream political Islam acts as a “gateway drug” to radical extremism in the form of Al Qaeda or ISIS. This thesis gained popularity in recent years, yet its validity is open to question and should be subjected to further scrutiny and analysis. I examine these questions in this article. Citation: Hashemi, Nader. 2021. Political Islam: A 40 Year Keywords: political Islam; Islamism; Islamic fundamentalism; Middle East; Islamic world; Retrospective. Religions 12: 130. Muslim Brotherhood https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020130 Academic Editor: Jocelyne Cesari Received: 26 January 2021 1. Introduction Accepted: 9 February 2021 Published: 19 February 2021 The year 2020 roughly coincides with the 40th anniversary of the rise of political Islam.1 While this trend in Muslim politics has deeper historical and intellectual roots, it Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral was approximately four decades ago that this subject emerged from seeming obscurity to with regard to jurisdictional claims in capture global attention. -

The Haqqani Network

October 2010 Jeffrey A. Dressler AFGHANISTAN REPORT 6 THE HAQQANI NETWORK FROM PAKISTAN TO AFGHANISTAN INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY of WAR Military A nalysis andEducation for Civilian Leaders Cover photo: Members of an Afghan-international security force pull security on a compound in Waliuddin Bak dis- trict, of Khost province, Afghanistan, Apr. 8, 2010. During the search, the security force captured a Haqqani facilita- tor, responsible for specialized improvised explosive device support and technical expertise for various militant networks. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Mark Salazar/Released) All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2010 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2010 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515, Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org ABOUT THE AUTHOR Jeffrey A. Dressler is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) where he studies security dynamics in southeastern and southern Afghanistan. He previously published the ISW report, Securing Helmand: Understanding and Responding to the Enemy (October 2009). Dressler’s work has drawn praise from members of the Marine Corps and the intelligence community for its understanding of the enemy network in southern Afghanistan and analysis of the military campaign in Helmand province over the past several years. Dressler was invited to Afghanistan in July 2010 to conduct research for General David Petraeus following his assumption of command. -

Congressional Testimony

Congressional Testimony “U.S. Counterterrorism Efforts in Syria: A Winning Strategy?” Thomas Joscelyn Senior Fellow, Foundation for Defense of Democracies Senior Editor, The Long War Journal Hearing before House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade Washington, DC September 29, 2015 ● ● 1726 M Street NW Suite 700 Washington, DC 20036 1 Chairman Poe, Ranking Member Keating, and other members of the committee, thank you for inviting me here today to speak about America’s counterterrorism efforts in Syria. The war in Syria is exceedingly complex, with multiple actors fighting one another on the ground and foreign powers supporting their preferred proxies. Iran and Hezbollah are backing Bashar al Assad’s regime, which is also now receiving increased assistance from Russia. The Islamic State (often referred to by the acronyms ISIS and ISIL) retains control over a significant amount of Syrian territory. Despite some setbacks at the hands of the U.S.-led air coalition and Kurdish ground forces earlier this year in northern Syria, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s organization has not suffered anything close to a knockout blow thus far. Sunni jihadists, led by Al Nusrah Front and its closest allies, are opposed to both the Islamic State and the Assad regime. Unfortunately, they have been the most effective anti-Assad forces for some time, as could be seen in their stunning advances in the Idlib province earlier this year. Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and other nations are all sponsoring proxies in the fight. Given the complexity of the war in Syria, it should be obvious that there are no easy answers. -

The Internal Conflict in the Global Jihad Camp

The Internal Conflict in the Global Jihad Camp Yoram Schweitzer The founding of the organization known as the Islamic State in the spring of 2013, and its June 2014 announcement of the establishment of the Islamic State under the leadership of the caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, caused a split among all organizations belonging to and identifying with the global jihad camp – a camp that until then had been led by al-Qaeda. The dispute began in April 2013 with al-Baghdadi’s unilateral declaration of a union between the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), an organization under his leadership that was a branch of al-Qaeda, and the Jabhat al-Nusra organization in Syria, led by Abu Mohammad al-Julani. The decision, which al-Baghdadi made without consulting al-Julani, set the two at odds; al-Julani quickly rejected the unification, while declaring his loyalty to al-Zawahiri, the emir of al-Qaeda and his supreme commander. For his part, al-Zawahiri tried unsuccessfully to mediate between the hostile parties and preserve unity. Thus in May 2013 he ruled that al-Baghdadi would remain responsible for Iraq, while al-Julani would be responsible for Syria. He also announced that Jabhat al-Nusra would become the Syrian branch of al-Qaeda and an official member of its cluster of alliances.1 After a year of additional but futile attempts at mediation and compromise, accompanied by grave mutual accusations by spokesmen of ISIS and al-Qaeda supporters, the feud reached a peak with al-Zawahiri’s declaration of February 2014, in which he disclaimed all responsibility for ISIS activity in Iraq and Syria, and the consequent expulsion of the organization from the al-Qaeda cluster of alliances.2 These events were followed by the announcement in late June 2014 by Islamic State spokesman Abu Muhammad al-‘Adnani of the founding of the Islamic State and the self-appointment of al-Baghdadi as caliph. -

CASD Cemiss Quarterly Winter 2009

WINTER 2009 Q UARTERLY YEAR VII WINTER 2009 PERSIAN GULF Iran’s regime gets weaker, Saudi Arabia’s influence in the region soars Diego Baliani 5 SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE An overview of South Eastern Europe and main trends for Centro Militare di Studi Strategici 2010 Paolo Quercia 11 CeMiSS Quarterly is a review COMMONWEALTH OF INDEPENDENT STATES EASTERN EUROPE supervised by CeMiSS director, Major General Giacomo Guarnera Towards a new security architecture in Europe? Andrea Grazioso 17 It provides a forum to promote the knowledge and understanding of THE AFGHAN THEATER international security affairs, military Afghanistan-Pakistan 2010 proof of facts of the new american strategy and other topics of significant interest. strategy Fausto Biloslavo 23 The opinions and conclusions expressed in the articles are those of AFRICA the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the 2010: Africa, yes you "could"! Italian Ministry of Defence. Maria Egizia Gattamorta 39 INDIA AND CHINA Military Center for Strategic Studies Department of International Relations The end of Chindia? Palazzo Salviati Nunziante Mastrolia 49 Piazza della Rovere, 83 00165 – ROME - ITALY LATIN AMERICA tel. 00 39 06 4691 3204 Economic recovery and political integration fax 00 39 06 6879779 Riccardo gefter wondrich 59 e-mail [email protected] ENERGY SECTOR Oil Rejected, renewable energy and energetic efficiency promoted Gerardo Iovane 65 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS The UN action in Somalia: between 2009 and 2010 valerio bosco 73 Negative balance for Russia in Central Asia Lorena Di Placido 83 FOCUS ON The importance of small and developing countries in solving crises in the International Community Slobodan Simic 89 Quarterly Year VII N° 4 - Winter 2009 Persian Gulf Iran’s regime gets weaker, Saudi Arabia’s influence in the region soars Diego Baliani In 2009, the balance of power between Iran and Saudi Arabia, the region’s two leading rival powers, was such that Iran got weaker and Saudi influence increased. -

Analysis of Nation-Building During Insurgency in U.S. Defense Policy Strategy

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2019 Analysis of Nation-Building during Insurgency in U.S. Defense Policy Strategy Joseph Valles Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Other International and Area Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Valles, Joseph, "Analysis of Nation-Building during Insurgency in U.S. Defense Policy Strategy" (2019). MSU Graduate Theses. 3453. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3453 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANALYSIS OF NATION-BUILDING DURING INSURGENCY IN U.S. DEFENSE POLICY STRATEGY A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Joseph Valles December 2019 Copyright 2019 by Joseph Valles ii ANALYSIS OF NATION-BUILDING DURING INSURGENCY IN U.S. -

The Effectiveness of the Drone Campaign Against Al Qaeda Central

The Effectiveness of the Drone Campaign against Al Qaeda Central. A Case Study Javier Jordán University of Granada (Spain) Preprint version: Javier Jordán, “The Effectiveness of the Drone Campaign against Al Qaeda Central: A Case Study”, Journal of Strategic Studies , Vol. 37, No 1 (2014), pp. 4- 29. Abstract This article examines the effects which the drone strike campaign in Pakistan is having on Al Qaeda Central. To that end, it constructs a theoretical model to explain how the campaign is affecting Al Qaeda’s capacity to carry out terrorist attacks in the United States and Western Europe. Although the results of one single empirical case cannot be generalised, they nonetheless constitute a preliminary element for the construction of a broader theoretical framework concerning the use of armed drones as part of a counter-terrorism strategy. Key Words: Al Qaeda, Terrorism, Intelligence, Drones, United States, Pakistan. Introduction Although it has tried to repeat its highly lethal attacks, Al Qaeda Central has been unable to strike successfully in the United States since 9/11 or in Western Europe since 7 July 2005 (London bombings). Logically, as with all complex social phenomena, the operational decline of the terrorist organisation is the result of multiple factors. This article focuses on just one: the campaign of drone strikes against Al Qaeda Central in Pakistan, particularly North Waziristan. A fruitful academic debate is taking place at present regarding the effectiveness of High Value Targeting (HVT) campaigns in the fight against terrorist organisations. Based on empirical studies involving relatively large samples, several authors question the effectiveness of such campaigns and even warn that they may be counterproductive.1 Others, however, also use empirical research to show that HVT reduces the effectiveness of terrorist organisations.