Myanmar and Rakhine State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Important Facts About the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - Emref

Important Facts about the 2015 Myanmar General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation (EMReF) 2015 October Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF 1 Important Facts about the 2015 General Election Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation - EMReF ENLIGHTENED MYANMAR RESEARCH ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT FOUNDATION (EMReF) This report is a product of the Information Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation EMReF is an accredited non-profit research Strategies for Societies in Transition program. (EMReF has been carrying out political-oriented organization dedicated to socioeconomic and This program is supported by United States studies since 2012. In 2013, EMReF published the political studies in order to provide information Agency for International Development Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010- and evidence-based recommendations for (USAID), Microsoft, the Bill & Melinda Gates 2012). Recently, EMReF studied The Record different stakeholders. EMReF has been Foundation, and the Tableau Foundation.The Keeping and Information Sharing System of extending its role in promoting evidence-based program is housed in the University of Pyithu Hluttaw (the People’s Parliament) and policy making, enhancing political awareness Washington's Henry M. Jackson School of shared the report to all stakeholders and the and participation for citizens and CSOs through International Studies and is run in collaboration public. Currently, EMReF has been regularly providing reliable and trustworthy information with the Technology & Social Change Group collecting some important data and information on political parties and elections, parliamentary (TASCHA) in the University of Washington’s on the elections and political parties. performances, and essential development Information School, and two partner policy issues. -

WFP Myanmar Country Brief in Numbers

In Numbers 3,385 mt of food assistance distributed US$585,800 cash based transfers made US$26.7 m six months (May-October 2018) net funding requirements, representing 8.6% of total needs WFP Myanmar 295,000 people Country Brief assisted 52% 48% in April 2018 April 2018 Operational Context Operational Updates Myanmar, the second largest country in Southeast Asia, is WFP successfully completed the April food amidst an important political and socio-economic distributions in Rakhine State. In Maungdaw District, transformation. Highly susceptible to natural disasters, WFP assisted 68,500 conflict-affected people, Myanmar ranks 3rd out of 187 countries in the global climate including 2,900 pregnant and lactating women and risk index. An estimated 37.5 percent of its 53 million population live near or below the poverty line. Most in the adolescent girls and 10,000 children under the age of country struggle with physical, social and economic access to five, from Muslim, Buddhist and Hindu communities sufficient, safe and nutritious food with women, girls, elderly, in 123 villages of Buthidaung and Maungdaw persons with disabilities and minorities affected most. Townships. Nearly one in three children under the age of five suffers In Sittwe District, WFP reached 109,500 internally from chronic malnutrition (stunting) while wasting prevails at displaced persons (IDPs) and other conflict affected seven percent nationally. Myanmar is one of the world's 20 populations in townships of Kyaukpyu, Kyauktaw, high tuberculosis burden countries. It is also among 35 Minbya, Mrauk-U, Myebon, Pauktaw, Rathedaung and countries accounting for 90 percent of new HIV infections Sittwe. -

Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Township Map - Rakhine State 92° E 93° E 94° E Tilin 95° E Township Myaing Yesagyo Pauk Township Township Bhutan Bangladesh Kyaukhtu !( Matupi Mindat Mindat Township India China Township Pakokku Paletwa Bangladesh Pakokku Taungtha Samee Ü Township Township !( Pauk Township Vietnam Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Nyaung-U !( Paletwa Saw Township Saw Township Ngathayouk !( Bagan Laos Maungdaw !( Buthidaung Seikphyu Township CHIN Township Township Nyaung-U Township Kanpetlet 21° N 21° Township MANDALAYThailand N 21° Kyauktaw Seikphyu Chauk Township Buthidaung Kyauktaw KyaukpadaungCambodia Maungdaw Chauk Township Kyaukpadaung Salin Township Mrauk-U Township Township Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Ponnagyun Township Township Minbya Rathedaung Sidoktaya Township Township Yenangyaung Yenangyaung Sidoktaya Township Minbya Pwintbyu Pwintbyu Ponnagyun Township Pauktaw MAGWAY Township Saku Sittwe !( Pauktaw Township Minbu Sittwe Magway Magway .! .! Township Ngape Myebon Myebon Township Minbu Township 20° N 20° Minhla N 20° Ngape Township Ann Township Ann Minhla RAKHINE Township Sinbaungwe Township Kyaukpyu Mindon Township Thayet Township Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Mindon Township !( Bay of Bengal Ramree Kamma Township Kamma Ramree Toungup Township Township 19° N 19° N 19° Munaung Toungup Munaung Township BAGO Padaung Township Thandwe Thandwe Township Kyangin Township Myanaung Township Kyeintali !( 18° N 18° N 18° Legend ^(!_ Capital Ingapu .! State Capital Township Main Town Map ID : MIMU1264v02 Gwa !( Other Town Completion Date : 2 November 2016.A1 Township Projection/Datum : Geographic/WGS84 Major Road Data Sources :MIMU Base Map : MIMU Lemyethna Secondary Road Gwa Township Boundaries : MIMU/WFP Railroad Place Name : Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) translated by MIMU AYEYARWADY Coast Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] Township Boundary www.themimu.info Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Yegyi Ngathaingchaung !( State/Region Boundary 2016. -

Rakhine State Census Report Volume 3 – K

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Rakhine State Census Report Volume 3 – K Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Rakhine State Report Census Report Volume 3 – K For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014, and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is now my hope that the main results, both Union and each of the State and Region reports, will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national and sub-national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and officers at the State/Region, District and Township Levels, and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. The technical support and our strong desire to follow international standards affirmed our commitment to strict adherence to the guidelines and recommendations, which form part of international best practices for census taking. -

Location Indicators by Indicator

ECCAIRS 4.2.6 Data Definition Standard Location Indicators by indicator The ECCAIRS 4 location indicators are based on ICAO's ADREP 2000 taxonomy. They have been organised at two hierarchical levels. 12 January 2006 Page 1 of 251 ECCAIRS 4 Location Indicators by Indicator Data Definition Standard OAAD OAAD : Amdar 1001 Afghanistan OAAK OAAK : Andkhoi 1002 Afghanistan OAAS OAAS : Asmar 1003 Afghanistan OABG OABG : Baghlan 1004 Afghanistan OABR OABR : Bamar 1005 Afghanistan OABN OABN : Bamyan 1006 Afghanistan OABK OABK : Bandkamalkhan 1007 Afghanistan OABD OABD : Behsood 1008 Afghanistan OABT OABT : Bost 1009 Afghanistan OACC OACC : Chakhcharan 1010 Afghanistan OACB OACB : Charburjak 1011 Afghanistan OADF OADF : Darra-I-Soof 1012 Afghanistan OADZ OADZ : Darwaz 1013 Afghanistan OADD OADD : Dawlatabad 1014 Afghanistan OAOO OAOO : Deshoo 1015 Afghanistan OADV OADV : Devar 1016 Afghanistan OARM OARM : Dilaram 1017 Afghanistan OAEM OAEM : Eshkashem 1018 Afghanistan OAFZ OAFZ : Faizabad 1019 Afghanistan OAFR OAFR : Farah 1020 Afghanistan OAGD OAGD : Gader 1021 Afghanistan OAGZ OAGZ : Gardez 1022 Afghanistan OAGS OAGS : Gasar 1023 Afghanistan OAGA OAGA : Ghaziabad 1024 Afghanistan OAGN OAGN : Ghazni 1025 Afghanistan OAGM OAGM : Ghelmeen 1026 Afghanistan OAGL OAGL : Gulistan 1027 Afghanistan OAHJ OAHJ : Hajigak 1028 Afghanistan OAHE OAHE : Hazrat eman 1029 Afghanistan OAHR OAHR : Herat 1030 Afghanistan OAEQ OAEQ : Islam qala 1031 Afghanistan OAJS OAJS : Jabul saraj 1032 Afghanistan OAJL OAJL : Jalalabad 1033 Afghanistan OAJW OAJW : Jawand 1034 -

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State”

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State” Table of Contents KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................... 2 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 5 1.1. POLITICAL PARTY LANDSCAPE IN RAKHINE STATE............................................................................ 7 1.2. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON FREE AND FAIR ELECTIONS .............................................................. 8 1.3. ELECTORAL SYSTEM IN MYANMAR ................................................................................................. 10 2. OBJECTIVE AND SCOPE OF THE STUDY ..................................................................................... 11 1. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 11 1.1. SAMPLING ...................................................................................................................................... 11 1.2. RESEARCH PROCESS ........................................................................................................................ 12 1.3. LIMITATION OF STUDY .................................................................................................................... 12 2. FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................ -

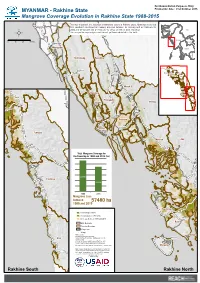

Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015

For Humanitarian Purposes Only MYANMAR - Rakhine State Production date : 21st October 2015 Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015 This map illustrates the evolution of mangrove extent in Rakhine State, Myanmar as derived Bhutan from Landsat-5 multispectral imagery acquired between 13 January and 23 February for Nepal Mindat 1988 and 30 January and 24 February for 2015 at 30m of pixel resolution. India China Town Bangladesh Bangladesh This is a preliminary analysis and has not yet been validated in the field. Paletwa Town Viet Nam Myanmar 0 10 20 30 Kms Laos Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Town Town Maungdaw Thailand Buthidaung Kyauktaw Cambodia Taungpyoletwea Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Town Buthidaung Kyauktaw Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Mrauk-U Town Maungdaw Rathedaung Mrauk-U Ponnagyun Town Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Pauktaw Minbya Sittwe Pauktaw Myebon Sittwe Myebon Ann Ann Mrauk-U Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu Ramree Ramree Toungup Rathedaung Mrauk-U Munaung Munaung Toungup Town Ann Thandwe Ponnagyun Thandwe Rathedaung Minbya Kyeintali Mindon Ma-Ei Town Town Town Gwa Gwa Ramree Minbya Town Ponnagyun Town Pauktaw Sittwe Pauktaw Town Sittwe Toungup Town Myebon Town Myebon Ann Toungup Town Total Mangrove Coverage for the Township in 1988 and 2015 (ha) Ann Town Thandwe Town 280986 Thandwe 223506 Kyaukpyu 1988 2015 Town Mangrove Loss between 57480 ha 1988 and 2015 Kyaukpyu New Mangrove area Kyeintali Town Remaining area 1988-2015 Ramree Decrease between 1988 and 2015 Town Ramree State Boundary Township Boundary Village-Tract Village Data sources: Toungup Landcover Analysis: UNOSAT Administrative Boundaries, Settlements: OCHA Munaung Gwa Town Roads: OSM Coordinate System: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N Contact: [email protected] File: REACH_MMR_Map_Rakhine_HVA_Mangrove_21OCT2015_A1 Munaung Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Gwa Town on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, associated, donors mentioned on this map. -

Zootaxa, Danio Aesculapii, a New Species of Danio

Zootaxa 2164: 41–48 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Danio aesculapii, a new species of danio from south-western Myanmar (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) SVEN O. KULLANDER & FANG FANG Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, PO Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Danio aesculapii, new species, is described from small rivers on the western slope of the Rakhine Yoma in south-western Myanmar. It is superficially similar to D. choprae from northern Myanmar in having a series of vertical bars anteriorly on the side, but differs from it and other species of Danio in having six instead of seven or more branched dorsal-fin rays, and from all other species of Danio except D. erythromicron and D. kerri in having 12 instead of 10 or 14 circumpeduncular scale rows. Key words: Rakhine Yoma, Thandwe, Danio choprae, endemism Introduction The cyprinid fish genus Danio Hamilton includes 14 small species in South and Southeast Asia (Kullander et al. 2009), as a rule diagnosable by distinct species-specific colour patterns. About half of the species of Danio have a pigment pattern that consists of one or more dark or light horizontal stripes (Fang, 1998). Among the others, Danio kyathit Fang differs in having the stripes broken up into rows of small brown spots, D. margaritatus (Roberts) has a pattern of small light spots on the sides, D. dangila (Hamilton) has rows of dark rings with light centres, and D. -

New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State?

CRS INSIGHT New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State? February 15, 2019 (IN11046) | Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) Approximately 250 Chin and Rakhine refugees entered into Bangladesh's Bandarban district in the first week of February, trying to escape the fighting between Burma's military, or Tatmadaw, and one of Burma's newest ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), the Arakan Army (AA). Bangladesh's Foreign Minister Abdul Momen summoned Burma's ambassador Lwin Oo to protest the arrival of the Rakhine refugees and the military clampdown in Rakhine State. Bangladesh has reportedly closed its border to Rakhine State. U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar Yanghee Lee released a press statement on January 18, 2019, indicating that heavy fighting between the AA and the Tatmadaw had displaced at least 5,000 people. She also called on the Rakhine State government to reinstate the access for international humanitarian organizations. The Conflict Between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw The AA was formed in Kachin State in 2009, with the support of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). In 2015, the AA moved some of its soldiers from Kachin State to southwestern Chin State, and began attacking Tatmadaw security bases in Chin State and northern Rakhine State (see Figure 1). In late 2017, the AA shifted more of its operations into northeastern Rakhine State. According to some estimates, the AA has approximately 3,000 soldiers based in Chin and Rakhine States. Figure 1. Reported Clashes between Arakan Army and Tatmadaw Source: CRS, utilizing data provided by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State

ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 1/2 RH PT Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State (Source: Myanmar Information Management Unit) http://themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/State_Map_D istrict_Rakhine_MIMU764v04_23Oct2017_A4.pdf ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 2/2 RH PT Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Rakhine State 92° EBANGLADESH 93° E 94° E 95° E Pauk !( Kyaukhtu INDIA Mindat Pakokku Paletwa CHINA Maungdaw !( Samee Ü Taungpyoletwea Nyaung-U !( Kanpetlet Ngathayouk CHIN STATE Saw Bagan !( Buthidaung !( Maungdaw District 21° N THAILAND 21° N SeikphyuChauk Buthidaung Kyauktaw Kyauktaw Kyaukpadaung Maungdaw Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Mrauk-U Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Mrauk-U District Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Minbya Pwintbyu Sittwe DistrictPonnagyun Pauktaw Sittwe Saku !( Minbu Pauktaw .! Ngape .! Sittwe Myebon Ann Magway Myebon 20° N RAKHINE STATE Minhla 20° N Ann MAGWAY REGION Sinbaungwe Kyaukpyu District Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu !( Mindon Ramree Toungup Ramree Kamma 19° N 19° N Bay of Bengal Munaung Toungup Munaung Padaung Thandwe District BAGO REGION Thandwe Thandwe Kyangin Legend .! State/Region Capital Main Town !( Other Town Kyeintali !( 18° N Coast Line 18° N Map ID: MIMU764v04 Township Boundary Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 State/Region Boundary Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 International Boundary Data Sources: MIMU Gwa Base Map: MIMU Road Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Kyaukpyu Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) Gwa translated by MIMU Maungdaw Mrauk-U Email: [email protected] Website: www.themimu.info Sittwe Ngathaingchaung Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Kilometers !( Thandwe 2017. May be used free of charge with attribution. 0 15 30 60 Yegyi 92° E 93° E 94° E 95° E Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

'Threats to Our Existence'

Threats to Our Existence: Persecution of Ethnic Chin Christians in Burma Chin Human Rights OrganizaƟ on Threats to Our Existence: Persecution of Ethnic Chin Christians in Burma September, 2012 © Chin Human Rights OrganizaƟ on 2 Montavista Avenue Nepean ON K2J 2L3 Canada www.chro.ca Photos © CHRO Front cover: Chin ChrisƟ ans praying over a cross they were ordered to destroy by the Chin State authoriƟ es, Mindat township, July 2010. Back cover: Chin ChrisƟ an revival group in Kanpetlet township, May 2010. Design & PrinƟ ng: Wanida Press, Thailand ISBN: 978-616-305-461-6 Threats to Our Existence: PersecuƟ on of ethnic Chin ChrisƟ ans in Burma i Contents CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................... i Figures and appendices .................................................................................................. iv Acronyms ....................................................................................................................... v DedicaƟ on ...................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ viii About the Chin Human Rights OrganizaƟ on................................................................... ix RaƟ onale and methodology ........................................................................................... ix Foreword .......................................................................................................................