Förstasida C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Report the Netherlands

Final National report from The Netherlands Crime Prevention Carousel Nicole Smits Tobias Woldendorp Final National report from The Netherlands Crime Prevention Carousel Amsterdam, 21 december 2006 Nicole Smits Tobias Woldendorp Met medewerking van: Eric Lugtmeijer DSP – groep BV Van Diemenstraat 374 1013 CR Amsterdam T: +31 (0)20 625 75 37 F: +31 (0)20 627 47 59 E: [email protected] W: www.dsp-groep.nl KvK: 33176766 A'dam Inhoudsopgave 1 Introduction - Description of the site 4 1.1 The Bijlmermeer 4 1.2 Description of the research area 7 1.3 Social fysical context of The Bijlmermeer 8 1.4 Method of research in The Netherlands 9 2 Answering the questionnaire 11 Introduction 11 2.1 Aims 11 2.2 Structure and Process 11 2.3 Changes in perception 12 2.4 Security and crime reduction 13 2.5 Design and Crime 16 2.6 Individual Participation 16 2.7 Participation of Police 16 2.8 Participation of residents 17 2.9 Acceptance 17 2.10 Success and Costs 17 2.11 Lessons learned during the renewal 18 2.12 Displacement 19 2.13 Costs 19 2.14 Outlook 19 3 Site visit reports 20 3.1 Introduction 20 3.2 What stroke you most in the area? 20 3.3 What lessons can your country learn from the visited project? 21 3.4 What advise would you give to the visited project? 22 3.5 Can you give references (good or bad examples) of projects in your own country? 23 4 Concluding observations 24 Appendix Appendix 1 Site visit reports 26 1.1 Site visit report from Germany 26 1.2 Site visit report from Hungary 32 1.3 Site visit report from Poland 33 1.4 Site visit report from the UK 39 1.5 Site visit report from the Netherlands 41 Appendix 2 Literature 45 Pagina 3 Final National report from The Netherlands DSP - groep 1 Introduction - Description of the site 1.1 The Bijlmermeer Perhaps internationally the most famous neighbourhood of The Netherlands. -

Tour Groot-Amsterdam

Tour Groot-Amsterdam Acht fetsroutes - vierentwintig essays Maurits de Hoog 3 Tour Groot-Amsterdam Acht fetsroutes - vierentwintig essays Maurits de Hoog ormgeving aura mits Gemeente Amsterdam December 2020 www.tourgrootamsterdam.nl mauritsdehoogsall.nl Met dan aan Maru Asmellash Marcel loemendal aroline omb hristiaan van es tte eddes os Gadet ric van der ooi rits almboom ri asveer livier van de anden on chaa eroen chilt aura mits art tuart asiem aa ic ermeulen Aat de ries nhoud Introductie 7 Dit is een doe-boek! 11 Route 1: Voorstad in een moeras - Homeic rommeniedi 2 - andschaseuilleton van het er- 2 - High streets Route 2: Gemengde stad rond de Zaan - angs de aan - aghettiat - Het Hem Route 3: Haven-Stad - Mauettes - en hub in Haven-tad - ordic eague - groen als motor Route 4: Het IJ komt erbij 0 - tedenbouw all-inclusive o meeliten - aterlein 0 2 - rong over het 0 Route 5: Binnenstad - Archiel van onbegreen waliteiten - tadsontwer groot idee - leine truces - Amsterdam 00 Route 6: Amstelstad - ibautas - Het nieuw midden van erualem - ietsring Route 7: Bijlmermeer - edesign ilmermeer 20 - he tri 2 - ntegratie A Route 8: Vecht links 22 - aar ees 20 2 - uiteneiland 20 2 - echt lins 2 Algemeen itbreidingslan tructuurschema Groot-Amsterdam 2 6 ntroductie De beste manier om een stad o regio te leren ennen is o de fets te staen. de website www.tourgrootamsterdam.nl vind e acht fetstochten van ieder twintig ilometer rond een station in de agglomeratie Amsterdam. De fetstochten leiden e langs biondere enomenen in een uitsnede van het verstedelit landscha in en rond de stad een stri ogesannen tussen ort rommeniedi in het noordwesten en ort ittermeer in het uidoosten. -

DE BODEM ONDER AMSTERDAM Een Geologische Stadswandeling

EEN GEOLOGISCHE STADSWANDELING Wim de Gans OVER DE AUTEUR Dr. Wim de Gans (Amersfoort, 1941) studeerde aardwetenschappen aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Na zijn afstuderen was hij als docent achtereenvolgens verbonden aan de Rijks Universiteit Groningen en de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Na deze universitaire loopbaan was hij jaren lang werkzaam als districtsgeoloog bij de Rijks Geologische Dienst (RGD), die in 1997 is overgegaan naar TNO. De schrijver is bij TNO voor de Geologische Dienst Nederland vooral bezig met het populariseren van de geologie van Nederland. Hij schreef talrijke publicaties en enkele boeken waaronder het Geologieboek Nederland (ANWB/TNO). DE BODEM ONDER AMSTERDAM EEN GEOLOGISCHE STADSWANDELING Wim de Gans VOORWOORD Wanneer je door de binnenstad van Amsterdam wandelt, is het moeilijk voor te stellen dat onder de gebouwen, straten en grachten niet alleen veen maar ook veel andere grondsoorten voorkomen die een belangrijk stempel hebben gedrukt op de ontwikkeling van de stad. Hier ligt een aardkundige geschiedenis die enkele honderdduizenden jaren omvat. Landijs, rivieren, zee en wind hebben allemaal bijgedragen aan de vorming van een boeiende en afwisselende bodem, maar ook een bodem waarop het moeilijk wonen of bouwen is. Hoewel de geologische opbouw onder de stad natuurlijk niet direct zichtbaar is, zijn de afgeleide effecten hiervan vaak wel duidelijk. Maar men moet er op gewezen worden om ze te zien. Vandaar dit boekje. Al wandelend en lezend gaat er een aardkundige wereld voor u open waaruit blijkt dat de samenstelling van de ondergrond van Amsterdam grote invloed heeft gehad op zowel de vestiging en historische ontwikkeling van de stad als op het bouwen en wonen, door de eeuwen heen. -

The Ice and the Real Estate on the Zuidas from The

THE ICE AND THE REAL INTRODUCTION ESTATE ON THE ZUIDAS The Zuidas is usually described as corporate and anonymous, a place without Amsterdam roots FROM THE LOGOLENGTH that could easily be picked up and put down RESEARCH ZUIDAS elsewhere in the world. But is this correct? Does this view do justice to the Zuidas? The project logolength is an Irene Janze artistic, mathematical research project that maps the Zuidas in a particular manner. Logos brand the Zuidas. They link the (business) Environment.................... owners to the towers. A logo provides for an History.................... image. You can measure the height of the logo, Local.................... or judge her strength or radiance. Public.......... Space.......... Sign.......... img 1 The measuring of the logolength fig. 2 Height meter 29 img 4 Polder map. Subtitle: VU and the Zuidas drawn on the military map of ca. 1848. Adaptation by J. Fokkema Maybe you think the logo is pretty, ugly, tough or boring and therefore condemn its location as well. One can also measure the content of a logo, by dissecting the logo into its stories. Did you know that the South-axis (Zuidas) was once a salt-axis? He immigrated from a place close to Paramaribo and expresses himself here in the ‘k’1 of the AkzoNobel logo. And what to think of gold diggers in Mongolia? They already knew 10.000 years ago that dinosaurs became birds. You can read about them in the logolength research of the VU logo: the griffin.2 The logos on the Zuidas refer to other times and distant places. They can dig and fly and take us to the stars, salt lakes, carrot juice, industries, glaciers, gold, oil, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Nauman or Damasio. -

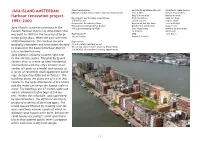

JAVA ISLAND AMSTERDAM Harbour Renovation

Client masterplan Architects apartment blocks Architects canal houses JAVA ISLAND AMSTERDAM DRO Amsterdam (Amsterdam’s planning department) Cruz & Ortiz Gerard Kruunenberg Harbour renovation project Kees Christiaanse Marlies Rohmer Developers and housing corporations Rudy Uytenhaak René van Zuuk SFB/BPF-bouw Sjoerd Soeters Cobien Heuff 1991-2000 Coöperatief Bouwbedrijf Moes Karelse en Van der Meer Jos van Eldonk Woningbouwvereniging Het Oosten Baneke Van der Hoeven Dana Ponec Java Island is a narrow peninsula in the Woningbouwvereniging ACOB Cees Nagelkerke Martine de Maeseneer Eastern Harbour District of Amsterdam that Jo Crepain Art Zaaijer was built in 1900 for the mooring of large Masterplanner AWG John Bosch ocean-going ships. When the port activities Sjoerd Soeters Geurst & Schulze shifted westwards, this harbour became Supervision gradually redundant and Amsterdam decided Sjoerd Soeters (masterplanner) to transform the Eastern Harbour District Ton Schaap (Amsterdam’s planning department) Jan de Waal (Amsterdam’s housing department) into a residential area. Java Island is uniquely located right next to the old city centre. The plan by Sjoerd Soeters aims to create an ideal residential environment with the city’s historic inner cordon of canals as a model and consists of a series of relatively small apartment build- ings, designed by different architects. The buildings along the quays are of a size that relates to the large dimensions of the island and the water yet keeps the human scale in mind. The buildings are 27 meters wide and each is divided into five bays of 5.4 me- ters. Within this structure, and supervised by Sjoerd Soeters, the different architects produced a variety of dwelling types. -

Amsterdam Zuidoost: De Bijlmermeer Amsterdam Zuidoost, Beter Bekend Als De Bijlmermeer, Is in 2007 Onderdeel Geworden Van De 40- Wijkenaanpak

http://kennisbank.platform31.nl/pages/27629/Amsterdam-Zuidoost-de-Bijlmermeer.html Amsterdam Zuidoost: de Bijlmermeer Amsterdam Zuidoost, beter bekend als De Bijlmermeer, is in 2007 onderdeel geworden van de 40- wijkenaanpak. De vernieuwing van de Bijlmer is echter al bijna twee decennia gaande. De wijk is in de jaren zestig ontwikkeld als het summum voor de moderne mens. Dit ideaal werd echter snel door de realiteit ingehaald, waardoor omvangrijke leegstand en ernstige leefbaarheidsproblemen ontstonden. Vanaf het begin van de jaren negentig is de vernieuwing grootschalig opgepakt en is het eerste voorbeeld geworden van de integrale aanpak, die landelijke navolging kreeg in het Grote Steden Beleid. Wijkbeschrijving De stad van morgen 'Nergens in de wereld is tot nu toe een mooiere en modernere stad van een dergelijke omvang tot uitvoering gekomen. De kans ligt er: het projekt voor het prettigste woonoord dat zich laat denken.' (burgemeester Van Hall, 1964) De Bijlmer werd in de jaren’ 60 aangekondigd als ‘De stad van morgen’ voor de mens van nu. Gebaseerd op de idealen van de CIAM en het plan ‘“De Stralende Stad” van CIAM’s belangrijkste voorhanger Le Corbusier, werden in hoog tempo flats neergezet. De hoogbouw in honingraatvorm maakte het mogelijk om te bouwen in hoge dichtheid en tegelijkertijd grote groene hoven te creëren die moesten bijdragen aan het vergroten van de collectiviteit. De wijk werd opgebouwd uit riante maar uniforme woningen met tal van collectieve voorzieningen per flatgebouw, auto's keurig uit het zicht opgeborgen in parkeergarages en gemotoriseerd verkeer gescheiden van fietsers en wandelaars. De nieuwe stad moet de Amsterdamse stadsontwikkeling opnieuw beroemd maken, net als in de jaren dertig het veelgeprezen Amsterdamse Uitbreidingsplan (AUP) van Van Eesteren. -

Gebiedsplan Bijlmer Centrum 2019

1 Gebiedsplan 2019 Bilmer Centrum 2 In dit gebiedsplan leest u wat de belangrikste onderwerpen zin in Bilmer Centrum en wat de gemeente samen met bewoners, ondernemers en maatschappelike organisaties in 2019 gaat doen. Inhoud Inleiding 3 Prioriteit 1 Verbeteren ontwikkelings-kansen jeugd 11 Prioriteit 2 Verminderen armoede 18 Prioriteit 3 Verbeteren woonklimaat 24 Prioriteit 4 Bevorderen lichamelike en geestelike gezondheid 32 Prioriteit 5 Bevorderen participatie en sociale cohesie 39 Prioriteit 6 Versterken buurteconomie, kunst en cultuuraanbod en verhogen duurzaam ondernemen 43 Meerjarenprogrammering 2019-2022 48 Colofon Dank aan bewoners(groepen), maatschappelike partners en bezoekers die hebben meegewerkt aan de totstandkoming van het gebiedsplan 2019. Dank aan Jeltje van Nuland en Paco Núñez. 3 Inleiding Voor u ligt het gebiedsplan 2019 van Bilmer Centrum. Het gebiedsplan beschrift de jaarlikse uitvoering van de gebiedsagenda 2019-2022. Met de gebiedsagenda signaleren de stadsdelen wat er buiten speelt en leeft; we laten zien wat de belangrikste ontwikkelingen, opgaven en kansen in het gebied zin. Die vertalen we naar prioriteiten en doelstellingen. Dat gebeurt op basis van de gebiedsanalyse, het coalitieakkoord en participatie met bewoners en betrokken partien. Dit gebiedsplan is een uitwerking van de activiteiten die nodig zin om de opgaven zoals omschreven in de gebiedsagenda 2019 te kunnen uitvoeren. Het gebiedsplan laat zien wat we in dat jaar gezamenlik willen bereiken. De activiteiten van het gebiedsplan gaan over de inzet op ‘meer, minder of anders’. Die inzet bestaat naast de reguliere inzet van bivoorbeeld basisvoorzieningen van de gemeente Amsterdam. Uiteraard bliven we alle actuele ontwikkelingen in deze periode nauwgezet volgen. Dat betekent dat we kunnen bisturen door activiteiten toe te voegen, aan te passen of te stoppen. -

Urban Europe.Indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10/11/16 / 13:03 | Pag

omslag Urban Europe.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10/11/16 / 13:03 | Pag. All Pages In Urban Europe, urban researchers and practitioners based in Amsterdam tell the story of the European city, sharing their knowledge – Europe Urban of and insights into urban dynamics in short, thought- provoking pieces. Their essays were collected on the occasion of the adoption of the Pact of Amsterdam with an Urban Agenda for the European Union during the Urban Europe Dutch Presidency of the Council in 2016. The fifty essays gathered in this volume present perspectives from diverse academic disciplines in the humanities and the social sciences. Fifty Tales of the City The authors — including the Mayor of Amsterdam, urban activists, civil servants and academic observers — cover a wide range of topical issues, inviting and encouraging us to rethink citizenship, connectivity, innovation, sustainability and representation as well as the role of cities in administrative and political networks. With the Urban Agenda for the European Union, EU Member States of the city Fifty tales have acknowledged the potential of cities to address the societal challenges of the 21st century. This is part of a larger, global trend. These are all good reasons to learn more about urban dynamics and to understand the challenges that cities have faced in the past and that they currently face. Often but not necessarily taking Amsterdam as an example, the essays in this volume will help you grasp the complexity of urban Europe and identify the challenges your own city is confronting. Virginie Mamadouh is associate professor of Political and Cultural Geography in the Department of Geography, Planning and International Development Studies at the University of Amsterdam. -

Wooncarrière in De Veranderende Stad a M S T E R D a M INHOUD

Wooncarrière in de veranderende stad A m s t e r d a m INHOUD Voorwoord Hoofdstukken: 1 Binding, wooncarrière en de veranderende stad 7 2 I Amsterdam 17 3 Een dorp in de stad 31 4 Stedelijk leven 43 2 5 Weg van Amsterdam 59 6 Verschillende buurten, verschillende mensen 73 Korte verantwoording van het onderzoek 83 Voetnoten 86 Colofon 88 Voorwoord Iedere twee jaar voeren de Gemeente Amsterdam en de Amsterdamse Federatie van Woningcorporaties een grootschalige enquête uit onder duizenden Amsterdammers. In dit onderzoek ‘Wonen in Amsterdam’ worden de woonwensen en de woonsituatie van Amsterdammers onderzocht. Wonen in Amsterdam geeft een goed en uitgebreid beeld van de woningmarkt met veel feiten en cijfers. Wat ontbreekt is het verhaal achter de cijfers. Voor dit onderzoek zijn daarom geen enquêtes afgenomen, maar gesprekken gevoerd met honderd Amsterdammers over hun woonsituatie. Het stedelijk wonen is weer populair. Steeds meer mensen kiezen bewust voor het stedelijk leven. Tegelijkertijd maken veel buurten in Amsterdam een proces van herwaardering door. Soms autonoom, soms gestimuleerd door investeringen door corporaties en de gemeente. Dit onderzoek vormt een overzicht van ervaringen van stedelingen op de woningmarkt. Deze woningmarkt bestaat uit een mozaïek van mensen en woningen en wordt gekenmerkt door een enorme diversiteit. Juist die diversiteit komt in dit boek naar voren. 5 In dit boek wordt de dynamiek van de stad gecombineerd met de individuele keuzes die mensen maken in hun wooncarrière. We zijn verheugd te zien dat de meeste geïnterviewde Amsterdammers tevreden zijn en ieder op zijn eigen wijze een binding met de buurt of stad heeft. -

18 Urban Renewal in the Bijlmermeer: Changing Strategies

Large housing estates: ideas, rise, fall and recovery The Bijlmermeer and beyond PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Technische Universiteit Delft, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. ir. K.Ch.A.M. Luyben, voorzitter van het College voor Promoties, in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 12 maart 2013 om 15.00 uur door Franciscus Anne Godefridus WASSENBERG doctorandus in de planologie geboren te Amsterdam Dit proefschrift is goedgekeurd door de promotor: Prof. emer. dr. ir. H. Priemus Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Rector Magnificus, voorzitter Prof. emer. dr. ir. H. Priemus, Technische Universiteit Delft, promotor Prof. dr. S. Musterd, Universiteit van Amsterdam Prof. dr. P. Hooimeijer, Universiteit Utrecht Prof. dr. W.A. Hafkamp, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam Prof. dr. J. van der Schaar, Universiteit van Amsterdam Prof. dr. ir. M.G. Elsinga, Technische Universiteit Delft Prof. dr. P.J. Boelhouwer, Technische Universiteit Delft Large housing estates: ideas, rise, fall and recovery The Bijlmermeer and beyond Frank Wassenberg The series Sustainable Urban Areas is published by IOS Press under the imprint Delft University Press IOS Press BV Nieuwe Hemweg 6b 1013 BG Amsterdam The Netherlands Fax +31 20 6870019 E-mail: [email protected] Sustainable Urban Areas is edited by OTB Research Institute for the Built Environment Delft University of Technology Jaffalaan 9 2628 BX Delft The Netherlands Phone +31 15 2783005 E-mail [email protected] http://www.otb.tudelft.nl Design: Cyril Strijdonk Ontwerpburo, Gaanderen; dtp: Itziar Lasa Printed in the Netherlands by Haveka, Alblasserdam ISSN 1574-6410; 48 (print) ISBN 978-1-61499-231-8 (print) ISSN 1879-8330; 48 (online) ISBN 978-1-61499-232-5 (online) NUR 755 Legal notice The publisher is not responsible for the use which might be made of the fol- lowing information. -

Water and Land Ur of the Netherlands

Water and Land ur of the netherlands Department of LanDscape architecture anD environmentaL Planning College of environmental Design, University of California, Berkeley printing: alonzo printing C ison design Water and Land introduction a stuDy tour of the netherLanDs prof. peter bosse L m a n n the birth of the idea for a study tour to the Netherlands developed after Assistant Professor Jennifer Brooke began research on the condition of reclaimed land in the San Francisco Bay Area. The low-lying tidal basins, formerly used for salt production, are now permanently open to tidal action. Large wetlands have emerged and gradually a new landscape will begin to take shape that will not necessarily resemble the original marshes of the Bay’s natural history. It will be a constructed landscape. The levees that protected the former salt flats followed a functional geometry in contrast to the evolving landscape that will become vegetated by successive plant communities and filled with birds and wildlife in a not entirely predictable fashion. Similarly, the Dutch polder (grazing land that is situated below sea level) has been converted to permanently flooded wetlands, and some of these wetlands are now 30 years old. In fall 2005, the catastrophic Hurricane Katrina occurred in the Mississippi Delta and gave the study tour additional impetus. During that fall semester, faculty in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning decided to concentrate efforts on the California Delta, which is formed by the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. We invited Jane Wolff of Washington University dep A rtment of la ndsc A pe A rchitecture A nd environment al p la nning a stuDy tour of the netherLanDs in Saint Louis to UC Berkeley as the Visiting Farrand condition of levees in the California Delta, students and Professor, to offer a design studio that would focus faculty in Jane Wolff’s design studio questioned the on the California Delta. -

Ra 170519Chvamstelarenametco

Gemeente Amsterdam CHV 2017.28 Amstel-Arena Inhoud Inleiding 3 1 Beleidskader 4 2 Historisch stedenbouwkundige analyse 5 2.1 Inleiding 5 2.2 Het landschap van de Groot-Duivendrechtse polder en Infrastructuur 6 2.3 De vormgeving van de Amstelscheg 17 2.4 De bedrijventerreinen Amstel I, II en III 21 2.5 Station Duivendrecht en omgeving 27 2.6 Centrumgebied Arena Poort 28 3 Conclusie en aanbevelingen 31 Bronnen 33 Colofon 33 2 Gemeente Amsterdam CHV 2017.28 Amstel-Arena Inleiding Monumenten en Archeologie heeft in opdracht van RVE Ruimte en Duurzaamheid een cultuurhistorische verkenning gemaakt van het gebied tussen Amstelstation en de omgeving van de Johan Cruijff Arena. Dit is gebeurd in het kader van de Gebiedsuitwerking Amstel-Arena (koers 2025) Het doel van de Gebiedsuitwerking is het nader bepalen van een ontwikkelstrategie voor het gebied tussen grofweg de omgeving Amstelstation en de Amsterdam ArenA en het aanjagen van nieuwe locaties voor gebiedsontwikkeling (incl. woningbouw) en de condities (infra, groen, voorzieningen) waaronder dit mogelijk is. Deze CHV is een bouwsteen van deze gebiedsuitwerking omdat een verslag is van het onderzoek naar de historische ontwikkeling van het gebied en brengt de voor de gebiedsstructuur bepalende kenmerken in kaart. 1. Begrenzing uitwerkingsgebied Amstel-Arena 3 Gemeente Amsterdam CHV 2017.28 Amstel-Arena 1 Beleidskader Naar aanleiding van de Modernisering van de Monumentenwet en de wijziging van artikel 3.1.6 van het Besluit ruimtelijke ordening (Bro, d.d.17 juni 2011, staatsblad 5 juli 2011, nr 339) dient per 1 januari 2012 bij het maken van bestemmingsplannen een beschrijving te worden opgenomen “van de wijze waarop met de in het gebied aanwezige cultuurhistorische waarden en in de grond aanwezige of te verwachten monumenten rekening is gehouden”.