Possibilities of University-Sponsored

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Johnny Cash by Dave Hoekstra Sept

Johnny Cash by Dave Hoekstra Sept. 11, 1988 HENDERSONVILLE, Tenn. A slow drive from the new steel-and-glass Nashville airport to the old stone-and-timber House of Cash in Hendersonville absorbs a lot of passionate land. A couple of folks have pulled over to inspect a black honky-tonk piano that has been dumped along the roadway. Cabbie Harold Pylant tells me I am the same age Jesus Christ was when he was crucified. Of course, this is before Pylant hands over a liter bottle of ice water that has been blessed by St. Peter. This is life close to the earth. Johnny Cash has spent most of his 56 years near the earth, spiritually and physically. He was born in a three-room railroad shack in Kingsland, Ark. Father Ray Cash was an indigent farmer who, when unable to live off the black dirt, worked on the railroad, picked cotton, chopped wood and became a hobo laborer. Under a New Deal program, the Cash family moved to a more fertile northeastern Arkansas in 1935, where Johnny began work as a child laborer on his dad's 20-acre cotton farm. By the time he was 14, Johnny Cash was making $2.50 a day as a water boy for work gangs along the Tyronza River. "The hard work on the farm is not anything I've ever missed," Cash admitted in a country conversation at his House of Cash offices here, with Tom T. Hall on the turntable and an autographed picture of Emmylou Harris on the wall. -

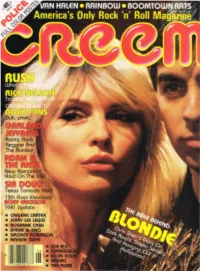

RUSH: but WHY ARE THEY in SUCH a HURRY? What to Do When the Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•

• CARLENE CARTER • JERRY LEE LEWIS • ROSANNE CASH • BYRNE & ENO • SMOKEY acMlNSON • MARVIN GAYE THE SONG OF INJUN ADAM Or What's A Picnic Without Ants? .•.•.•••••..•.•.••..•••••.••.•••..••••••.•••••.•••.•••••. 18 tight music by brit people by Chris Salewicz WHAT YEAR DID YOU SAY THIS WAS? Hippie Happiness From Sir Doug ....••..•..••..•.••••••••.•.••••••••••••.••••..•...•.••.. 20 tequila feeler by Toby Goldstein BIG CLAY PIGEONS WITH A MIND OF THEIR OWN The CREEM Guide To Rock Fans ••.•••••••••••••••••••.•.••.•••••••.••••.•..•.•••••••••. 22 nebulous manhood displayed by Rick Johnson HOUDINI IN DREADLOCKS . Garland Jeffreys' Newest Slight-Of-Sound •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.••..••. 24 no 'fro pick. no cry by Toby Goldstein BLONDIE IN L.A. And Now For Something Different ••••.••..•.••.••.•.•••..••••••••••.••••.••••••.••..••••• 25 actual wri ting by Blondie's Chris Stein THE PSYCHEDELIC SOUNDS OF ROKY EmCKSON , A Cold Night For Elevators •••.••.•••••.•••••••••.••••••••.••.••.•••..••.••.•.•.••.•••.••.••. 30 fangs for the memo ries by Gregg Turner RUSH: BUT WHY ARE THEY IN SUCH A HURRY? What To Do When The Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•. 32 mortgage payments mailed out by J . Kordosh POLICE POSTER & CALENDAR •••.•••.•..••••••••••..•••.••.••••••.•••.•.••.••.••.••..•. 34 LONESOME TOWN CHEERS UP Rick Nelson Goes Back On The Boards .•••.••••••..•••••••.••.•••••••••.••.••••••.•.•.. 42 extremely enthusiastic obsewations by Susan Whitall UNSUNG HEROES OF ROCK 'N' ROLL: ELLA MAE MORSE .••.••••.•..•••.••.• 48 control -

Johnny Cash Returns to ‘Stamping Ovation’ Legendary Singer Is Second Inductee Into Multi-Year Music Icons Series

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Mark Saunders June 5, 2013 [email protected] 202-268-6524 usps.com/news Release No. 13-056 To obtain a high-resolution of the stamp image for media use only, please email [email protected]. Johnny Cash Returns to ‘Stamping Ovation’ Legendary Singer is Second Inductee into Multi-Year Music Icons Series NASHVILLE — John Carter Cash, Rosanne Cash, Larry Gatlin, Jamey Johnson, The Oak Ridge Boys, The Roys, Marty Stuart, Randy Travis and other entertainers paid tribute to Johnny Cash as he was inducted today into the Postal Service’s Music Icons Forever stamp series at the Grand Ole Opry’s Ryman Auditorium. “With his gravelly baritone and spare percussive guitar, Johnny Cash had a distinctive musical sound — a blend of country, rock ’n’ roll and folk — that he used to explore issues that many other popular musicians of his generation wouldn’t touch,” said U.S. Postal Service Board of Governors member Dennis Toner. “His songs tackled sin and redemption, good and evil, selfishness, loneliness, temptation, love, loss and death. And Johnny explored these themes with a stark realism that was very different from other popular music of that time.” “It is an amazing blessing that my father, Johnny Cash be honored with this stamp. Dad was a hardworking man, a man of dignity. As much as anything else he was a proud American, always supporting his family, fans and country. I can think of no better way to pay due respect to his legacy than through the release of this stamp,” said singer-songwriter, producer John Carter Cash, Johnny Cash’s son. -

The Big List (My Friends Are Gonna Be) Strangers Merle Haggard 1948 Barry P

THE BIG LIST (MY FRIENDS ARE GONNA BE) STRANGERS MERLE HAGGARD 1948 BARRY P. FOLEY A LIFE THAT'S GOOD LENNIE & MAGGIE A PLACE TO FALL APART MERLE HAGGARD ABILENE GEORGE HAMILITON IV ABOVE AND BEYOND WYNN STEWART-RODNEY CROWELL ACT NATURALLY BUCK OWENS-THE BEATLES ADALIDA GEORGE STRAIT AGAINST THE WIND BOB SEGER-HIGHWAYMAN AIN’T NO GOD IN MEXICO WAYLON JENNINGS AIN'T LIVING LONG LIKE THIS WAYLON JENNINGS AIN'T NO SUNSHINE BILL WITHERS AIRPORT LOVE STORY BARRY P. FOLEY ALL ALONG THE WATCHTOWER BOB DYLAN-JIMI HENDRIX ALL I HAVE TO DO IS DREAM EVERLY BROTHERS ALL I HAVE TO OFFER IS ME CHARLIE PRIDE ALL MY EX'S LIVE IN TEXAS GEORGE STRAIT ALL MY LOVING THE BEATLES ALL OF ME WILLIE NELSON ALL SHOOK UP ELVIS PRESLEY ALL THE GOLD IN CALIFORNIA GATLIN BROTHERS ALL YOU DO IS BRING ME DOWN THE MAVERICKS ALMOST PERSUADED DAVID HOUSTON ALWAYS LATE LEFTY FRIZZELL-DWIGHT YOAKAM ALWAYS ON MY MIND ELVIS PRESLEY-WILLIE NELSON ALWAYS WANTING YOU MERLE HAGGARD AMANDA DON WILLIAMS-WAYLON JENNINGS AMARILLO BY MORNING TERRY STAFFORD-GEORGE STRAIT AMAZING GRACE TRADITIONAL AMERICAN PIE DON McLEAN AMERICAN TRILOGY MICKEY NEWBERRY-ELVIS PRESLEY AMIE PURE PRAIRIE LEAGUE ANGEL FLYING TOO CLOSE WILLIE NELSON ANGEL OF LYON TOM RUSSELL-STEVE YOUNG ANGEL OF MONTGOMERY JOHN PRINE-BONNIE RAITT-DAVE MATTHEWS ANGELS LIKE YOU DAN MCCOY ANNIE'S SONG JOHN DENVER ANOTHER SATURDAY NIGHT SAM COOKE-JIMMY BUFFET-CAT STEVENS ARE GOOD TIMES REALLY OVER MERLE HAGGARD ARE YOU SURE HANK DONE IT WAYLON JENNINGS AUSTIN BLAKE SHELTON BABY PLEASE DON'T GO MUDDY WATERS-BIG JOE WILLIAMS BABY PUT ME ON THE WAGON BARRY P. -

The Justice in Policing Act of 2020 in the U.S

June 23, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker of the House 1236 Longworth House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Honorable Kevin McCarthy Republican Leader 2468 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader McCarthy: Since the killing of George Floyd just one month ago, our country has seen protests grow, attitudes shift, and calls for change intensify. We in the music and entertainment communities believe that Black lives matter and have long decried the injustices endured by generations of Black citizens. We are more determined than ever to push for federal, state, and local law enforcement programs that truly serve their communities. Accordingly, we are grateful for movement of the Justice in Policing Act of 2020 in the U.S. House of Representatives and urge its quick passage. The Justice in Policing Act is not about marginal change; it takes bold steps that will make a real, positive difference for law enforcement and the communities they serve. We celebrate the long- overdue rejection of qualified immunity, emphasizing that law enforcement officers themselves are not above the law – that bad cops must be held accountable and victims must have recourse. We applaud the provisions to ban chokeholds and no-knock warrants, to establish a national police misconduct registry, to collect data and improve investigations into police misconduct, to promote de-escalation practices, to establish comprehensive training programs, and to update and enhance standards and practices. This legislation will not only promote justice; it will establish a culture of responsibility, fairness, and respect deserving of the badge. Our communities and nation look to you to take a stand in this extraordinary moment and we respectfully ask that you vote YES on the Justice in Policing Act of 2020. -

Two Different Contractors Will Build Middle Schools

Volume XXXV No. 12 sewaneemessenger.com Friday, April 5, 2019 Village Two Diff erent Updates Contractors Will Build by Leslie Lytle Messenger Staff Writer Middle Schools Two years ago Frank Gladu by Leslie Lytle, Messenger Staff Writer who oversees the Sewanee Village project made a promise “not to cut At the March 29 meeting, the Franklin County School Board selected my beard until we build some- Biscan Construction to build the new North Middle School and South- thing.” Gladu will soon get to cut land Constructors to build South Middle School. Of the fi ve contractors his beard. At the April 2 Sewanee bidding, three bid on both schools, Southland among them. Th e bids by Village update meeting, Gladu an- R. G. Anderson and Barton Malow Construction off ered a discounted nounced the long-awaited ground- price if awarded the contract for both schools. Th e combined bid from breaking for the new bookstore the contractors selected, $40,588,200, was nearly a million dollars less along with reviewing other high than the next lowest bidder, Barton Malow, even after taking the dis- momentum initiatives, narrowing count into account. U.S. Hwy. 41A and construction Biscan’s $20,258,500 bid includes HVAC for the Huntland School of a mixed-use grocery and apart- gym, as requested in the bid package. Th e County Commission allocated ment building. $48 million for construction of the middle schools. “The bookstore underwent a “It’s good not to be up against the wall,” said Construction Manager redesign to conform to the bud- Gary Clardy who pointed out unforeseen costs could arise. -

Teacher's Guide

TEACHER’S GUIDE FOR GRADES 3–6 Teach Language Arts Through Lyric Writing Made possible by generous support from Teach Language Arts Through Lyric Writing We’re always together, always forever, Nothing can stop us now When I’m with you the sky turns blue Feels like I’m floating on a cloud Words & Music • Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum 1 Teach Language Arts Through Lyric Writing TEACHER’S GUIDE FOR GRADES 3 - 6 Table of Contents Overview 3 Lessons 1. What Is Songwriting? 7 2. Parts of a Song 11 3. Subject and Title 18 4. Theme and Message 23 5. Rhythm and Syllables 28 6. Rhyme 32 7. Creating Strong Images 36 8. Focused Lyric-Writing Day 41 9. Revision 46 Preparing for Songwriter Workshop 47 Guidelines for Lyric Submission to Museum 48 10. Copyright and Post-Unit Reflection 51 Appendix Common Core Curriculum Standards 55 Music Curriculum Standards 56 Supplemental Materials 57 Pre-Unit Assessment Rubric 58 Final Lyric Assessment Rubric 59 Songwriter Manuscripts 64 Acknowledgments Inside Back Cover “ I was twelve when I learned my first three chords on guitar and wrote my first song. My life changed forever... Music became the way I told my stories.” —Taylor Swift Since 1979, the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum has been helping students tell their stories through its innovative Words & Music program. Over 35 years, nearly 100,000 students have learned how to write song lyrics while developing key skills in language arts. Not only does Words & Music teach core curriculum but it also connects young people to Nashville’s music community, pairing participating classes with songwriters who turn students’ work into finished songs that are performed in an interactive workshop. -

The Unbroken Circle the Musical Heritage of the Carter Family

The Unbroken Circle The Musical Heritage Of The Carter Family 1. Worried Man Blues - George Jones 2. No Depression In Heaven - Sheryl Crow 3. On The Sea Of Galilee - Emmylou Harris With The Peasall - Sisters 4. Engine One-Forty-Three - Johnny Cash 5. Never Let The Devil Get - The Upper Hand Of You - Marty Stuart And His Fabulous - Superlatives 6. Little Moses - Janette And Joe Carter 7. Black Jack David - Norman And Nancy Blake With - Tim O'brien 8. Bear Creek Blues - John Prine 9. You Are My Flower - Willie Nelson 10. Single Girl, Married Girl - Shawn Colvin With Earl And - Randy Scruggs 11. Will My Mother Know - Me There? The Whites - With Ricky Skaggs 12. The Winding Stream - Rosanne Cash 13. Rambling Boy - The Del Mccoury Band 14. Hold Fast To The Right - June Carter Cash 15. Gold Watch And Chain - The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band - With Kris Kristofferson Produced By John Carter Cash (except "No Depression" produced by Sheryl Crow) Engineered And Mixed By Chuck Turner (except "Engine One-Forty-Three" mixed by John Carter Cash) Executive Assistant To The Producer Andy Wren Mixing Assistant Mark "Hank" Petaccia Recorded at Cash Cabin Studio, Hendersonville, Tennessee unless otherwise listed. Mixed at Quad Studios, Nashville, Tennessee All songs by A.P. Carter Peer International Corp. (BMI) Lyrics reprinted by permission. The Production Team Would Like To Thank: Laura Cash, Anna Maybelle Cash, Joseph Cash, Skaggs Family Records, Joseph Lyle, Mark Rothbaum, LaVerne Tripp, Debbie Randal, The guys at Underground Sound, Rita Forrester, Flo Wolfe, Dale Jett, Pat and Sharen Weber, Hope Turner, Chet and Erin, Connie Smith, Lou and Karen Robin, Cathy and Bob Sullivan, Kirt Webster, Bear Family Records, Wayne Woodard, Mark Stielper, Carlene, Renate Damm, Lin Church, David Ferguson, Kelly Hancock, Karen Adams, Lisa Trice, Lisa Kristofferson and kids, Nancy Jones, DS Management, Rick Rubin, Ron Fierstein, Les Banks, John Leventhal, Sumner County Sheriff's Department, our buddies at TWRA, and most of all God. -

A Message from Karen Pearl He Holiday Season Is Always a Special an Integral Part of the Healthcare System, and Time at God’S Love We Deliver

THE NEWSLETTER OF GOD’S LOVE WE DELIVER NUTRITION: OUR SIGNATURE DIFFERENCE GODSLOVEWEDELIVER.ORG WINTER 2017 A Message From Karen Pearl he holiday season is always a special an integral part of the healthcare system, and time at God’s Love We Deliver. Our these results could move us closer to that volunteers, once again, eagerly jumped reality. Tin to help prepare and deliver a record 4,400 I thank everyone who participated in special meals at Thanksgiving and 4,600 our volunteer and fundraising activities in Winter Feast meals in December, making the 2016. Your compassion and generosity are holidays much more joyful for our clients, inspiring, and you have made it possible for their children and their senior caregivers. I us to achieve great success. was delighted to see so many familiar faces Here are but a few examples. At the helping in the kitchen and delivering holiday Golden Heart Awards in October, emcee meals throughout New York City and into Neil Patrick Harris joined a star-studded New Jersey and Nassau and Westchester line-up of entertainers, celebrity chefs and Counties. The many warm thank you notes models, along with our Board, Trustees, Celebrating the Cookbook with Board members Jon Gilman & Scott Bruckner and messages of gratitude from clients and Leadership Council, genLOVE members their families demonstrate the tremendous and friends to honor three people who have impact our volunteers and supporters made supported God’s Love in numerous ways: true labor of love from our beloved Board in clients’ lives this season. Thank you all so supermodel and entrepreneur Karlie Kloss, member Jon Gilman and dedicated volunteer much. -

Rosanne Cash Episode Transcript

VOICES IN THE HALL ROSANNE CASH EPISODE TRANSCRIPT PETER COOPER Welcome to Voices in the Hall, presented by the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. I’m Peter Cooper. Today’s guest, Rosanne Cash. ROSANNE CASH Coming here as a teenager, I thought Nashville was kind of backwards. The girls were still really curling their hair and we were all like dead straight hair hippies growing up near Los Angeles. And we were infused with the Pop and Rock of Southern California in the late 60s and early 70s. And it was like coming to a little bit of a different time. My dad cast an awfully large shadow and people were happy to try to look through me to see him and try to find out what of him was in me, and I wanted to know who I was without him. You can’t really explain inspiration. I don’t know how inspiration works. But I have been doing this long enough that I have a sense of mastery about at least knowing when it’s right. PETER COOPER It’s Voices in the Hall with Rosanne Cash. “Tennessee Flat Top Box” - Rosanne Cash (King’s Record Shop / Columbia) PETER COOPER That was “Tennessee Flat Top Box,” recorded by Rosanne Cash, written by her father Johnny Cash, and featuring stellar guitar work from the great Randy Scruggs. Rosanne Cash is a heralded songwriter, a luminous vocalist, an essayist, a deep thinker, and the author of one of the greatest musical memoirs I’ve ever read, a book simply called Composed. -

Advance Program Notes Rosanne Cash the River and the Thread Friday, December 11, 2015, 7:30 PM

Advance Program Notes Rosanne Cash The River and the Thread Friday, December 11, 2015, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Rosanne Cash The River and the Thread Biographies ROSANNE CASH, vocals, guitar Rosanne Cash and her new album, The River and the Thread With The River and the Thread, Rosanne Cash has added the next chapter to a remarkable period of creativity. In 2015, Cash was awarded three Grammy Awards: her album won for Best Americana Album and the track Feather’s Not a Bird, which she co-wrote with her longtime collaborator (and husband) John Leventhal, won for Best American Roots Performance and Best American Roots Song. Her last two albums, Black Cadillac (2006) and The List (2009), were both nominated for GRAMMY Awards; The List—an exploration of essential songs as selected and given to Cash by her father, Johnny Cash—was also named Album of the Year by the Americana Music Association. In addition, her best-selling 2010 memoir, Composed, was described by the Chicago Tribune as “one of the best accounts of an American life you will likely ever read.” Cash, who has charted 21 Top 40 country singles, including 11 number ones, wrote all of the new album’s songs with John Leventhal, who also served as producer, arranger, and guitarist. Featuring a long list of guests—from young guns like John Paul White (The Civil Wars) and Derek Trucks to such legends as John Prine, Rodney Crowell, and Tony Joe White—The River and the Thread is a kaleidoscopic examination of the geographic, emotional, and historic landscape of the American South. -

CENTER for the PERFORMING ARTS at PENN STATE ONSTAGE © Clay Patrick Mcbride Patrick © Clay Today’S Performance Is Sponsored By

CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS AT PENN STATE ONSTAGE © Clay Patrick McBride Patrick © Clay Today’s performance is sponsored by Richard and Sally Kalin COMMUNITY ADVISORY COUNCIL The Community Advisory Council is dedicated to strengthening the relationship between the Center for the Performing Arts and the community. Council members participate in a range of activities in support of this objective. Nancy VanLandingham, chair Bonnie Marshall Lam Hood, vice chair Pieter Ouwehand Melinda Stearns Judy Albrecht Lillian Upcraft William Asbury Pat Williams Lynn Sidehamer Brown Nina Woskob Philip Burlingame Deb Latta student representatives Eileen Leibowitz Brittany Banik Ellie Lewis Stephanie Corcino Christine Lichtig Jesse Scott Mary Ellen Litzinger CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS AT PENN STATE presents Rosanne Cash The River & The Thread Rosanne Cash, vocals and guitar John Leventhal, guitars, vocals, and music director Kevin Barry, guitars Glenn Patscha, keyboards Zev Katz, bass Dan Rieser, drums and percussion 7:30 p.m. Thursday, April 9, 2015 Eisenhower Auditorium Tonight’s program will be announced from the stage. The concert includes one intermission. sponsors Richard and Sally Kalin media sponsor BIG FROGGY 101 Some photographs and moving images have been generously provided by: James Jaworowicz and The Jack Robinson Archive, Memphis, Tennessee; Dave Anderson, Little Rock, Arkansas; Oxford American, A Magazine of the South; and The Library of Congress. Rosanne Cash appears by arragement with Opus 3 Artists and Cross Road Management. The Center for the Performing Arts at Penn State receives state arts funding support through a grant from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, a state agency funded by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency.