SECMOL (A): Envisioning Radical Change in Ladakh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ladakh Travels Far and Fast

LADAKH TRAVELS FAR AND FAST Sat Paul Sahni In half a century, Ladakh has transformed itself from the medieval era to as modern a life as any in the mountainous regions of India. Surely, this is an incredible achievement, unprecedented and even unimagin- able in the earlier circumstances of this landlocked trans-Himalayan region of India. In this paper, I will try and encapsulate what has happened in Ladakh since Indian independence in August 1947. Independence and partition When India became independent in 1947, the Ladakh region was cut off not only physically from the rest of India but also in every other field of human activity except religion and culture. There was not even an inch of proper road, although there were bridle paths and trade routes that had been in existence for centuries. Caravans of donkeys, horses, camels and yaks laden with precious goods and commodities had traversed the routes year after year for over two millennia. Thousands of Muslims from Central Asia had passed through to undertake the annual Hajj pilgrimage; and Buddhist lamas and scholars had travelled south to Kashmir and beyond, as well as towards Central Tibet in pursuit of knowledge and religious study and also for pilgrimage. The means of communication were old, slow and outmoded. The postal service was still through runners and there was a single telegraph line operated through Morse signals. There were no telephones, no newspapers, no bus service, no electricity, no hospitals except one Moravian Mission doctor, not many schools, no college and no water taps. In the 1940s, Leh was the entrepôt of this part of the world. -

TA 7417- IND: Support for the National Action Plan on Climate Change

TA7417-IND Support for the National Action Plan for Climate Change Support to the National Water Mission TA 7417 - IND: Support for the National Action Plan on Climate Change Support to the National Water Mission Final Report September 2011 Appendix 1 India Water Systems PREPARED FOR Government of India Governments of Punjab, Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu Asian Development Bank Support to the National Water Mission NAPCC ii Appendix 1 India Water Systems Appendix 1 India Water Systems Support to the National Water Mission NAPCC ii Appendix 1 India Water Systems Support to the National Water Mission NAPCC iii Appendix 1 India Water Systems SUMMARY OF ABBREVIATIONS A1B IPCC Climate Change Scenario A1 assumes a world of very rapid economic growth, a global population that peaks in mid-century and rapid introduction of new and more efficient technologies. A1 is divided into three groups that describe alternative directions of technological change: fossil intensive (A1FI), non-fossil energy resources (A1T) and a balance across all sources (A1B). A2 IPCC climate change Scenario A2 describes a very heterogeneous world with high population growth, slow economic development and slow technological change. ADB Asian Development Bank AGTC Agriculture Technocrats Action Committee of Punjab AOGCM Atmosphere Ocean Global Circulation Model APHRODITE Asian Precipitation - Highly-Resolved Observational Data Integration Towards Evaluation of Water Resources - a observed gridded rainfall dataset developed in Japan APN Asian Pacific Network for Global Change Research AR Artificial Recharge AR4 IPCC Fourth Assessment Report AR5 IPCC Fifth Assessment Report AWM Adaptive Water Management B1 IPCC climate change Scenario B1 describes a convergent world, with the same global population as A1, but with more rapid changes in economic structures toward a service and information economy. -

Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru Series 2, Volume 60

Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru Series 2, Volume 60 April 15- May 31, 1960 1. Members of the Chinese Delegation1 Jagat Mehta from Kannampilly Chinese Foreign Office handed over following list of Chou En-lai's party. Begins: 1. Chou En-lai Premier of the State Council. 2. Chen Yi Vice Premier of the State Council and Minister for Foreign Affairs. 3. Chang Han-fu Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs. 4. ChangYen Deputy Director of the Office in Charge of Foreign Affairs, State Council. 5. Chiao Kuan-hua Assistant Minister for Foreign Affairs. 6. Lo Ching-chang Deputy Director of the Premier's Secretariat. 7. Chang Wen-chin Director of the First Asian Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 8. Kang Mao-chao Deputy Director of the Indo Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 9. Li Shu-huai Department Deputy Director, Ministry of Public Security. 1 Telegram from K.M. Kannampilly, Charge d' Affaires, Indian Embassy, Peking, to Jagat Mehta, Director, Northern Division, MEA, 7 April 1960. This volume begins on 15 April but three items dated 7, 8 and 14 April have been included here as they pertain to Chou's visit. 10.Huag Shu-tsu Deputy Director of the Health Protection Bureau, Ministry of Public Health. 11. Chou Chia-ting Secretary of the Premier's Secretariat. 12. Pu Shou-chang Secretary of the Premier's Secretariat. 13. HoChien Secretary of the Premier's Secretariat. 14. Han Hsu Assistant Director of the Protocol Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 15. Ma Lieh Secretary of the Premier's Secretariat. 16. Ni Yung Heh Assistant Director of the First Asian Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. -

Magazine1-4 Final.Qxd (Page 2)

Restore Geological ...Page 4 SUNDAY, MAY 17, 2020 INTERNET EDITION : www.dailyexcelsior.com/sunday-magazine Making Spirituality...Page 3 Saint, Scholar from Ladakh Nawang Tsering Shakspo With that, Prime Minister Bakshi inducted Kushok Bakula into his ministry and accordingly Kushok Bakula Rinpoche became Deputy Minister with the portfolio of Ladakh Affairs. According to reliable Soon after Ladakh was granted the UT status, Dr. Karan Singh, the former Sadr-i-Riyasat sources, it was none other than Nehru himself who directed Bakshi Sahib to create the Ladakh Affairs post of Jammu and Kashmir and a close associate of 19th Kushok Bakula Rinpoche, said in a state- in the Government. ment: "All empires invariably come to an end, J&K no exception." On the other hand, Kushok As the celebration of the 2500 Buddha Jayanti was drawing near, the Indian Government Bakula Rinpoche had forecast long ago that "Ladakh would attain the UT status, though there was looking for a Buddhist religious leader who could influence the Buddhist community of could be delay, adding that the destiny lies in its separation from the Jammu and Kashmir India. In 1955, the Indian Government sent Kushok Bakula to Tibet to assess the situation State". there, on account of the massive Chinese build-up in Tibet and the Red Army intrusion in that Padma Bhushan 19th Kushok Bakula Rinpoche (1917-2003), a saint and scholar from country. The Government of India also nominated Kushok Bakula as a member of the Ladakh, remained a pre-eminent religious and political figure in Ladakh for over half a cen- National Committee for Buddha Jayanti celebration in the year 1956, headed by the then tury, marked by great social and political changes. -

Page1final.Qxd (Page 2)

daily Follow us: Daily Excelsior JAMMU, FRIDAY, JULY 2, 2021 REGD. NO. JK-71/21-23 Vol No. 57 12 Pages ` 5.00 ExcelsiorRNI No. 28547/65 No. 181 AC to approve Good, digital governance prime motive of Govt: LG projects above Rs 20 cr Excelsior Correspondent Far-reaching reforms of Modi Govt JAMMU, July 1: The Government today ordered that projects above Rs 20 crore will benefitted J&K, Ladakh: Dr Jitendra be approved by the Administrative Council (AC) now onwards. Fayaz Bukhari An order to this effect was Union Ministers to start visiting UT again issued by Chief Secretary Dr SRINAGAR, July 1: Union Arun Kumar Mehta. Minister of State Develop- cers from 10 States, Dr Jitendra eral governance initiatives He brought forth the trans- As per the order, all propos- ment of North Eastern Region Singh said that Modi undertaken by the Government formational changes pursued by als for administrative approval (DoNER), MoS PMO, Government is committed to for Jammu & Kashmir including Government through the of projects above Rs 20 crore Personnel, Public Grievances, Transparency and "Justice for the long-pending cadre review, Mission Karmayogi, wherein will be placed for consideration Pensions, Atomic Energy and and approval of the Space, Dr Jitendra Singh Sinha urges all to Administrative Council after today said that many far- concurrence by the Finance reaching reforms of Modi participate in Department. Government like Prevention Delimitation meets Expert Panel to visit *Watch video on www.excelsiornews.com Excelsior Correspondent Srinagar Hospitals : DB of Corruption Act, abolition of JAMMU, July 1: Excelsior Correspondent interviews for Group C and D Lieutenant Governor Manoj A view of lightning in the sky during thunderstorm in Jammu on Thursday night which brought SRINAGAR, July 1: The posts and more than 800 Sinha today appealed to all slight relief for Jammuites from scorching heat. -

“Repair, Renovation and Restoration of Water Bodies- Encroachment on Water Bodies and Steps Required to Remove the Encroachment and Restore the Water Bodies”

10 STANDING COMMITTEE ON WATER RESOURCES (2015-16) SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENATION. “Repair, Renovation and Restoration of Water Bodies- Encroachment on Water Bodies and Steps Required to Remove the Encroachment and Restore the Water Bodies”. TENTH REPORT LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2016 / Shravana,1938 (Saka) 1 TENTH REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON WATER RESOURCES (2015-16) (SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENATION. “Repair, Renovation and Restoration of Water Bodies- Encroachment on Water Bodies and Steps Required to Remove the Encroachment and Restore the Water Bodies”. Presented to Lok Sabha on 02.08.2016 Laid on the Table of Rajya Sabha on 02.08.2016 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2016/ Shravana,1938 (Saka) 2 CONTENTS Part – I REPORT Page No. COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (2015-2016) (iii) INTRODUCTION (v) Chapter – I Introductory 1 Chapter – II - State of Water Bodies in the country 4 - Minor Irrigation Census 4 - Reasons for increase/ decrease in total number of water bodies 5 - Survey of water bodies by the Ministry 7 - Classification of Water Bodies 9 - Measures taken to revive perishing water bodies 12 Chapter – III - Encroachment on Water Bodies 16 - Extent of encroachment 16 - Impact of encroachment on water bodies 21 - Action against encroachers 24 - Monitoring mechanism for prevention and removal of encroachments 26 (a) Monitoring mechanism under Repair, Renovation and Restoration 26 (RRR) Scheme (b) -

Ladakh-Minutes.Pdf

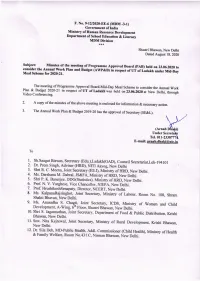

F. No. 9-12l2020-EE-6 (MDM -3-t) Government of India Ministry of Human R$ource Development Department of School Education & Literacy MDMDivision *** Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi Dated August I E, 2020 Subject: Minutes of the meeti-ng programme of Approvar Board @AB) herd on 23.06.2020 to consider the Annual work plan and Budget (Awp&B) In respect of ur of Ladakh under Mid_Day Meal Scheme for 2020-21. of Programme Approval lte lecting Board-Mid-Day Meal Scheme to consider the Annual Work -. &^^ Bu-dcet lLalt 2020-21 in respect of uT of Ladekh was held on 2tlt.ff.2t|20 r.i"*'ixr]r[,r,r.rgn Video Conferencing. "i 2' A copy oft}e minutes ofthe above meeting is enclosed for information & nec€ssaq/ action. 3. The Annual Work Plan & Budget 2019_20 has the approval of Secretary (SE&L). (Arnab D Under Secreta Tel. 011- E-mail: [email protected] To I !h S_aueat Biswas, Secretary @du.),Ladakh(GAD), Council Secrerariat,Leh_ l94l0l 2 Dr. Prem Singh, Adviser (HRD), NITI Aayog, New Delhi 3 Shri R. C. Meena, Joint Secretary (EE.I), Ministry of HRD, New Delhi. 4 Ms. Darshana M. Dabral, JS&FA, Ministry of HRD, New ielhi. 5 hri P. K. Bane{ee, DDG(Statistics), Ministry of HRD, New Delhi. 6 Prof. N. V. Varghese, Vice Chancellor, NIEpA, New Delhi. 7 Prof. HrushikeshSenapaty, Director, NCERT, New Delhi. 8 Ms. IGlpanaRajsinghot, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Labour, Room No. 10g, Sham Shakti Bhavan, New Delhi. Ms' Anuradha 9. S. chagti, Joint Secretary, ICDS, Ministry of women and child Devetopmenr, A-Wing. -

Government of India Ministry of Commerce & Industry

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY DEPARTMENT FOR PROMOTION OF INDUSTRY AND INTERNAL TRADE RAJYA SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. 133. TO BE ANSWERED ON FRIDAY, THE 29TH NOVEMBER, 2019. FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS FOR BUSINESSESIN JAMMU, KASHMIR AND LADAKH *133. SHRI BINOY VISWAM: Willthe Minister of COMMERCE ANDINDUSTRY be pleased to state: (a) the financial implications forbusinesses and the economy in Jammu,Kashmir and Ladakh since 5th August,2019; and (b) whether the Ministry has taken anysteps to reinvigorate the economy inJammu, Kashmir and Ladakh? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY (SHRI PIYUSH GOYAL) (a) & (b): Full potential of businesses and economy in Jammu, Kashmir &Ladakh regions could not be realized for the last 70 years as the people of Jammu and Kashmir have suffered from terrorist violence and separatism supported from across the border for the past many decades. On account of article 35A and certain other constitutional ambiguities, the people of these regions were denied full rights enshrined in the Constitution of India and other benefits of various Central Laws that were being enjoyed by other citizens of the country. After the declaration issued by the President under article 370, based on the recommendation of the Parliament and reorganization of the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir into Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir and Union Territory of Ladakh, all such aspects have been addressed and the people of these regions can now realize full potential in all sectors of economy and businesses like in other parts of the country. Due to these recent decisions, certain precautionary measures taken initially have already been substantially relaxed. -

Justifying Autonomy for Ladakh Martijn Van Beek Aarhus University, Denmark

Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 18 Number 1 Himalayan Research Bulletin: Solukhumbu Article 9 and the Sherpa, Part Two: Ladakh 1998 True Patriots: Justifying Autonomy for Ladakh Martijn van Beek Aarhus University, Denmark Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation van Beek, Martijn (1998) "True Patriots: Justifying Autonomy for Ladakh," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 18: No. 1, Article 9. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol18/iss1/9 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. True Patriots: Justif ying Autonomy for Ladakh Martijn van Beek Department of Ethnography and Social Anthropology Aarhus University, Denmark email: [email protected] When the first Ladakh Hill Development Council Minster joined in and the Governor of the State, General (Leh) was sworn in on 3 September 1995, Le.h District K.V. Krishna Rao, addressed the first meeting of the in the Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir regained a Council saying: measure of the autonomy that the Kingdom of Ladakh "Today, we have gathered here to mark one of the had lost in the 1830s .1 The Ladakh Autonomous Hill most important turning points in the history of this Development Councils Act 1995, decreed by the great land. -

Government of India Ministry of Home Affairs Lok Sabha

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2417 TO BE ANSWERED ON THE 03RD DECEMBER, 2019/AGRAHAYANA 12, 1941 (SAKA) DETENTION IN J&K 2417. SHRI DAYANIDHI MARAN: Will the Minister of HOME AFFAIRS be pleased to state: (a) the total number of persons in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) detained by the State and grounds for detention, itemized and with dates of detention, place of arrest and current status and lodging; (b) the total cost incurred by the Government towards implementation of the abrogation of Article 370 and the re-organization of J&K in terms of personnel deployed, cost of supplies, travel expenditure, detention of persons, communication and medical facilities; (c) the details thereof itemized; (d) whether there has been loss of business and economic impact since the abrogation of Article 370; and (e) if so, the details thereof and the corrective measures taken by the Government in this regard, and the comparison of fiscal data corresponding to this period across the last 15 years? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (SHRI G. KISHAN REDDY) (a) To prevent commission of offences involving breach of peace, activities prejudicial to the security of the State and maintenance of public order, 5161 persons including stone pelters, OGWs, separatists, etc. were taken into preventive custody in Kashmir Valley since 4th August, 2019. Out of these, presently 609 persons are under preventive detentions. These detentions have been made under statutory provisions by the concerned Magistrates. -2/… -2- LS.US.Q.NO.2417 FOR 03.12.2019 (b) & (c) No separate assessment has been made of cost incurred towards personnel deployed, cost of supplies, travel expenditure, detention of persons, communication and medical facilities, etc. -

National Mission on Himalayan Studies (NMHS) NMHS Annual Progress Report – Pro Forma

National Mission on Himalayan Studies (NMHS) NMHS Annual Progress Report – Pro forma Kindly fill the NMHS Annual Progress Report segregated into following 11 segments, as applicable to the objectives & quantifiable outcomes of your NMHS Project. 1. Project Information 2. Project Site Details 3. Project Activities Chart w.r.t. Timeframe [Gantt or PERT] 4. Financial and Resource Information 5. Equipment and Asset Information 6. Expenditure Statement and Utilization Certificate (UC) 7. Project Beneficiary Groups 8. Project Progress Summary (as applicable to the project) 9. Project Linkages (with concerned Institutions/ State Agencies) 10. Knowledge Products – Publication, recommendations, etc. 11. Project Concluding Remarks Kindly attach a descriptive Annexure/ Files separately for the segments marked for the detailed description required. Please let us know in case of any query at: [email protected] NMHS 2020 NMHS-Annual Progress Report (APR) Pro Forma Page 1 of 19 NMHS Progress Report (Period from 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020) 1. Project Information Project ID: NMHS/MG-2017 Sanction Date: 22/11/2017 Project Title: Understanding Ladakh’s socio-ecological processes to provide inputs for landscape-level development strategies BTG: PI and Affiliation Pankaj Raina, Wildlife Warden, Leh (Institution): Department of Wildlife Protection, UT Ladakh Name & Address of the Co-PI, if any: n/a Structured Major activities of the project during the year 2019-20 were focused on Abstract - data collection to spatially cover the Ladakh landscape across different detailing the seasons. These activities includes occupancy surveys and camera current year trapping in Hemis National Park which have been completed. Currently progress [Word camera trapping exercise is being expanded at Ladakh landscape level. -

Utll2020 the ADMINISTRATION of UNION TERRITORY of LADAKH GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT E-Mail: [email protected]

1/1277/2021 ~~ F.No.LAlGAD(DRPSC)UTLl2020 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT E-mail: [email protected] UT Secretariat, Ladakh Dated:-1B.OB.2021 Subject:- Study tour of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Urban Development (2020-21) to Leh w.e.f 25th of August, 2021. Reference:-LAFEAS-UD019/10/2021-UD Dated: 26.07.2021 from Lok Sabha Secretariat. Order No:-142-LA (GAD) of 2021 Dated: -18.08.2021 In continuation to the Order No: 133-LA (GAD) of 2021 dated: 30.07.2021 regarding the study tour of Standing Committee on Housing and Urban Development Department which is scheduled to visit Leh w.e.f zs" August 2021, as per the program annexed herewith. The visit is being facilitated by SBI, Canara Bank, Bank of India, and NBCC&HUDCO in coordination with UT Administration. Accordingly, in order to ensure smooth and hassle free visit of the Standing Committee, the following Officers/Departments are hereby assigned the responsibilities/ duties as indicated against each. S.No Assignment Name of the Officer Responsibility assigned 1. Program Co-ordination Smt. Zahida Bano Coordination with other Director Housing & agencies i.e. Urban Development a). To Coordinate and keep Department. liaison with the Nodal organization ie. SBI. b).To keep liaison with all other concerned Departments. 2. Meeting with the Smt. Zahida Bano All arrangement at venue of Ladakh Director Housing & the meeting and Administration/LAHDCs Urban Development coordination with the Department. departments for making presentations. 3. Deployment of Liaison Sh. Shrikant Will deploy liaison officers Officers Balasaheb Suse.