A Case Study of Tobacco Control in Twenty-First Century Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 What's Wrong with the Employee Free Choice Act?

6 What’s Wrong with the Employee Free Choice Act? Richard A. Epstein he first one hundred days of the Obama administration have been marked by its determination to pass the revolu- T tionary Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), which was introduced in Congress on March 10, 2009. As of this writing, it looks as though the bill will not pass this year, given the unanimous Republican opposition to it in the Senate. But the issue is likely to be revived again during the Obama presidency, as it has been before, so it is important to examine its provisions because it raises important issues of principle. In addition, it has gathered an impressive level of political and intellectual support. In particular, the EFCA has received the endorsement of the Democratic National Convention Platform Committee of prominent economists, under the aegis of the Economic Policy Institute, and of President Obama and Vice President Biden. In a recent congressional hearing before the 110th Congress on February 8, the EFCA was defended as the means to return to the management-labor balance under the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (the NLRA, in its original form is commonly referred to as the Wagner Act), said to be the surest way to revive the fortunes of a shrinking middle class. The reality, however, is otherwise. The EFCA would hamper the efficiency of labor markets in ways that make the road to economic 89 90 REACTING TO THE SPENDING SPREE recovery far steeper than necessary. Generally, it will severely hurt the very persons whom it intends to help. -

Large Firm Dynamics and Secular Stagnation: Evidence from Japan and the U.S

Bank of Japan Working Paper Series Large Firm Dynamics and Secular Stagnation: Evidence from Japan and the U.S. Yoshihiko Hogen* [email protected] Ko Miura** [email protected] Koji Takahashi*** [email protected] No.17-E-8 Bank of Japan June 2017 2-1-1 Nihonbashi-Hongokucho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 103-0021, Japan ***Research and Statistics Department (currently at the Monetary Affairs Department) *** Research and Statistics Department *** Research and Statistics Department (currently at the Financial System and Bank Examination Department) Papers in the Bank of Japan Working Paper Series are circulated in order to stimulate discussion and comments. Views expressed are those of authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank. If you have any comment or question on the working paper series, please contact each author. When making a copy or reproduction of the content for commercial purposes, please contact the Public Relations Department ([email protected]) at the Bank in advance to request permission. When making a copy or reproduction, the source, Bank of Japan Working Paper Series, should explicitly be credited. Large Firm Dynamics and Secular Stagnation: Evidence from Japan and the U.S. Yoshihiko Hogeny Ko Miuraz Koji Takahashix June 2017 Abstract Focusing on the recent secular stagnation debate, this paper examines the role of large …rm dynamics as determinants of productivity ‡uctuations. We …rst show that idiosyncratic shocks to large …rms as well as entry, exit, and reallocation e¤ects account for 30 to 40 percent of productivity ‡uctuations in Japan and the U.S. -

No. 144 Journal of East Asian Libraries

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2008 Number 144 Article 15 2-1-2008 No. 144 Journal of East Asian Libraries Journal of East Asian Libraries Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Libraries, Journal of East Asian (2008) "No. 144 Journal of East Asian Libraries," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2008 : No. 144 , Article 15. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2008/iss144/15 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JOURNAL 圖書 OF 图书 EAST 図書 ASIAN 도서 LIBRARIES No. 144 February 2008 Council on East Asian Libraries The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. ISSN 1087-5093 TABLE OF CONTENTS Number 144 February 2008 From the President i Articles Ping Situ New Concept of Collection Management: A Survey of Library Space-related Issues 1 Guo-hua Wang LLOLI: Language Learning Oriented Library Instruction 16 Meng Zhan and Fei Yu Analysis and Digital Processing of the 1911-1949 China Literary Collection 21 Reports Report on the Working Meeting of The North American Coordinating Council on Japanese Library Resources 27 Report on the First NCC Image Use Protocol Task Force Meeting 35 2006-2007 CEAL Statistical Report 42 Grand Opening of T. H. Tsien Library in Nanjing University: an International Celebration 70 New Appointments 72 Retirements Bill McCloy 73 Charles Wu 75 Announcements 77 Indexes 79 Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. -

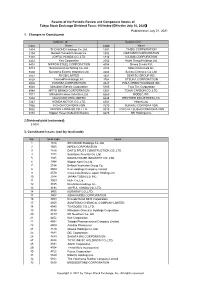

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

A PARTNER for CHANGE the Asia Foundation in Korea 1954-2017 a PARTNER Characterizing 60 Years of Continuous Operations of Any Organization Is an Ambitious Task

SIX DECADES OF THE ASIA FOUNDATION IN KOREA SIX DECADES OF THE ASIA FOUNDATION A PARTNER FOR CHANGE A PARTNER The AsiA Foundation in Korea 1954-2017 A PARTNER Characterizing 60 years of continuous operations of any organization is an ambitious task. Attempting to do so in a nation that has witnessed fundamental and dynamic change is even more challenging. The Asia Foundation is unique among FOR foreign private organizations in Korea in that it has maintained a presence here for more than 60 years, and, throughout, has responded to the tumultuous and vibrant times by adapting to Korea’s own transformation. The achievement of this balance, CHANGE adapting to changing needs and assisting in the preservation of Korean identity while simultaneously responding to regional and global trends, has made The Asia Foundation’s work in SIX DECADES of Korea singular. The AsiA Foundation David Steinberg, Korea Representative 1963-68, 1994-98 in Korea www.asiafoundation.org 서적-표지.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:42 서적152X225-2.indd 4 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 2 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 A PARTNER FOR CHANGE Six Decades of The Asia Foundation in Korea 1954–2017 Written by Cho Tong-jae Park Tae-jin Edward Reed Edited by Meredith Sumpter John Rieger © 2017 by The Asia Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission by The Asia Foundation. 서적152X225-2.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 2 17. -

Where Have All the Fairies Gone? Gwyneth Evans

Volume 22 | Number 1 | Issue 83, Autumn Article 4 10-15-1997 Where Have All the Fairies Gone? Gwyneth Evans Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Recommended Citation Evans, Gwyneth (1997) "Where Have All the Fairies Gone?," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Where Have All the Fairies Gone? Abstract Examines a number of modern fantasy novels and other works which portray fairies, particularly in opposition to Victorian and Edwardian portrayals of fairies. Distinguishes between “neo-Victorian” and “ecological” fairies. Additional Keywords Byatt, A.S. Possession; Crowley, John. Little, Big; Fairies in literature; Fairies in motion pictures; Jones, Terry. Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book; Nature in literature; Wilson, A.N. Who Was Oswald Fish? This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss1/4 P a g e 12 I s s u e 8 3 A u t u m n 1 9 9 7 M y t h l o r e W here Have All the Fairies Gone? G wyneth Evans As we create gods — and goddesses — in our own Crowley's Little, Big present, in their very different ways, image, so we do the fairies: the shape and character a contrast and comparison between imagined characters an age attributes to its fairies tells us something about the of a Victorian and/or Edwardian past and contemporary preconceptions, taboos, longings and anxieties of that age. -

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

Senate Democrats Progress on EFCA Compromise by Jay P

Senate Democrats Progress on EFCA Compromise by Jay P. Krupin and Steven Swirsky July 2009 The past several days have brought potentially significant developments with respect to Senate Democrats’ efforts to enact labor law reform and bring the Employee Free Choice Act to a vote on the Senate floor. Reports have circulated that a consensus has begun to emerge among Senate Democrats for a bill that would remove EFCA’s controversial provisions eliminating secret ballot elections where a union has obtained signatures from more than 50 percent of the employees in the proposed bargaining unit, and instead would provide for significantly faster NLRB-conducted elections, within five to ten days of the filing of a representation petition. The bill would also provide for greater access to employees and to employer property during the campaign period. Presently, NLRB-conducted elections are typically held an average of 45 days after the union files a petition. Along with faster elections, the reported compromise would include increased access by unions to employer premises to campaign among employees, as well as increased restrictions on employer campaign rights. EFCA’s other most controversial component, compulsory binding arbitration of the economic and other terms of initial collective bargaining agreements where the parties do not quickly reach agreement, is reported to remain a part of the compromise bill. While the Democrats reached 60 votes in the Senate when Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania switched his party affiliation from Republican to Democrat and Al Franken was finally declared the victor over Norm Coleman in Minnesota, the fact is that there remain a substantial block of Democratic senators who have expressed doubt about EFCA’s card check language and who have indicated that they are not prepared to support a bill that would eliminate secret ballot elections. -

Itraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List March 2021

iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List March 2021 Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List 1 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List...........................................3 2 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final vs. Series 34................................................ 5 3 Further information .....................................................................................6 Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 2 T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List 1 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List IHS Markit Ticker IHS Markit Long Name ACOM ACOM CO., LTD. JUSCO AEON CO., LTD. ANAHOL ANA HOLDINGS INC. FUJITS FUJITSU LIMITED HITACH HITACHI, LTD. HNDA HONDA MOTOR CO., LTD. CITOH ITOCHU CORPORATION JAPTOB JAPAN TOBACCO INC. JFEHLD JFE HOLDINGS, INC. KAWHI KAWASAKI HEAVY INDUSTRIES, LTD. KAWKIS KAWASAKI KISEN KAISHA, LTD. KINTGRO KINTETSU GROUP HOLDINGS CO., LTD. KOBSTL KOBE STEEL, LTD. KOMATS KOMATSU LTD. MARUB MARUBENI CORPORATION MITCO MITSUBISHI CORPORATION MITHI MITSUBISHI HEAVY INDUSTRIES, LTD. MITSCO MITSUI & CO., LTD. MITTOA MITSUI CHEMICALS, INC. MITSOL MITSUI O.S.K. LINES, LTD. NECORP NEC CORPORATION NPG-NPI NIPPON PAPER INDUSTRIES CO.,LTD. NIPPSTAA NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION NIPYU NIPPON YUSEN KABUSHIKI KAISHA NSANY NISSAN MOTOR CO., LTD. OJIHOL OJI HOLDINGS CORPORATION ORIX ORIX CORPORATION PC PANASONIC CORPORATION RAKUTE RAKUTEN, INC. RICOH RICOH COMPANY, LTD. SHIMIZ SHIMIZU CORPORATION SOFTGRO SOFTBANK GROUP CORP. SNE SONY CORPORATION Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 3 T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List SUMICH SUMITOMO CHEMICAL COMPANY, LIMITED SUMI SUMITOMO CORPORATION SUMIRD SUMITOMO REALTY & DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD. TFARMA TAKEDA PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY LIMITED TOKYOEL TOKYO ELECTRIC POWER COMPANY HOLDINGS, INCORPORATED TOSH TOSHIBA CORPORATION TOYOTA TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 4 T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List 2 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final vs. -

Spring 2012: IUC Newsletter

IUC NewsletterSpring 2012 Dear IUC Alumni and Friends, As the fiftieth anniversary of the IUC approaches, I am delighted to report that the state of the IUC community is stronger than ever. Thanks to the prodigious efforts of the IUC Alumni Association Executive Board, we are now in communication with 94% of all living alumni —a number that makes me beam with pride. As a sign of our ever-deepening network, many of you have been actively getting in touch with us and with each other, re-kindling friendships with former classmates, and making new connections with graduates from other classes. Oakland A’s vs Seattle Mariners game, Sunday, July 8, 2012 Getting to know our alumni has been the most exciting aspect at 1:00 p.m. in Oakland of my work as Executive Director. It has been an honor and privilege to meet with so many of you in person, and to get to 2013 Association for Asian know you through email, LinkedIn, and Facebook. IUC gradu- Studies IUC Reception, ates have made outstanding contributions to every dimension Saturday, March 23, 2013, in San Diego of the international understanding of Japan: from research, education, and translation to law, business, journalism, diplo- IUC 50th Anniversary Gala macy, the fine arts, popular culture, and cuisine. Each year, Celebration, Fall 2013 the number of alumni accomplishments grows and the di- See page 13 for details. versity of your endeavors expands to meet the needs of a changing world. Here are some choice facts about the IUC alumni com- munity that I have come to cherish, and that every gradu- ate should know and take pride in: *Eight IUC alumni have received the Order of the Rising Sun, undoubtedly more than any other U.S. -

The Employee Free Choice Act: the Biggest Change in Labor Law in 60 Years by Robert Quinn and John Leschak

LABOR LAW REGIONAL LABOR REVIEW, Fall 2009 The Employee Free Choice Act: The Biggest Change in Labor Law in 60 Years by Robert Quinn and John Leschak One of the most contentious proposals of the 2008 Presidential campaign and of the current Congressional season in Washington is the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA). Supported by President Obama and opposed by Senator John McCain and most other Republicans, EFCA would be the most significant change to federal labor law in over sixty years. First, EFCA would allow the National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”) to certify a union without an election if a majority of workers voluntarily sign cards authorizing a union to represent them (this provision is also known as “card check”). Second, EFCA would impose new penalties on employers who violate workers’ rights during initial organizing campaigns. And third, EFCA would permit bargaining disputes between an employer and union to be decided by arbitration during first-time contract negotiations. However, several powerful groups are opposed to any change. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has launched a vociferous campaign against EFCA’s “Card Check” provision, which they claim will lead to intimidation and coercion in the workplace.1 Congressional Republicans have also been outspoken opponents of card check. Last February, Republican Senators Jim DeMint (S.C.) and Mike Enzi (Wyo.) introduced the Secret Ballot Protection Act, S. 478. This bill would make it illegal for an employer to voluntarily recognize a union through card check and would require NLRB elections. While many are opposed to EFCA, it cannot be denied that reform is needed. -

Ranking of Stocks by Market Capitalization(As of End of Jan.2018)

Ranking of Stocks by Market Capitalization(As of End of Jan.2018) 1st Section Rank Code Issue Market Capitalization \100mil. 1 7203 TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION 244,072 2 8306 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group,Inc. 115,139 3 9437 NTT DOCOMO,INC. 105,463 4 9984 SoftBank Group Corp. 98,839 5 6861 KEYENCE CORPORATION 80,781 6 9432 NIPPON TELEGRAPH AND TELEPHONE CORPORATION 73,587 7 9433 KDDI CORPORATION 71,225 8 7267 HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 69,305 9 8316 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group,Inc. 68,996 10 7974 Nintendo Co.,Ltd. 67,958 11 7182 JAPAN POST BANK Co.,Ltd. 66,285 12 6758 SONY CORPORATION 65,927 13 6954 FANUC CORPORATION 60,146 14 7751 CANON INC. 58,005 15 6902 DENSO CORPORATION 54,179 16 4063 Shin-Etsu Chemical Co.,Ltd. 53,624 17 8411 Mizuho Financial Group,Inc. 52,124 18 6594 NIDEC CORPORATION 52,025 19 9983 FAST RETAILING CO.,LTD. 51,647 20 4502 Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited 50,743 21 7201 NISSAN MOTOR CO.,LTD. 49,108 22 8058 Mitsubishi Corporation 48,497 23 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 48,159 24 6098 Recruit Holdings Co.,Ltd. 45,095 25 5108 BRIDGESTONE CORPORATION 43,143 26 6503 Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 42,782 27 9022 Central Japan Railway Company 42,539 28 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 41,877 29 9020 East Japan Railway Company 41,824 30 6301 KOMATSU LTD. 41,162 31 3382 Seven & I Holdings Co.,Ltd. 39,765 32 6752 Panasonic Corporation 39,714 33 4661 ORIENTAL LAND CO.,LTD. 38,769 34 8766 Tokio Marine Holdings,Inc.